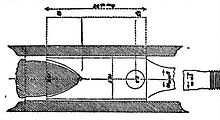

Carabine à tige

The carabine à tige (sometimes called a stem rifle or a pillar breech rifle) was a type of black-powder, muzzle-loading rifle invented by Louis-Etienne de Thouvenin. The method was an improvement of the invention of another Frenchman, Henri-Gustave Delvigne. Delvigne had developed chambered carbines and rampart rifle-muskets so that when forced against the chamber rim by ramming (with three strokes of a heavy ram), the bullet would become deformed and flatten, so as to expand in diameter against the inside of the bore, allowing the bullet to press against the rifling grooves. When fired, the bullet accompanied the rifling and spun. This was an early attempt to work around one of the greatest hindrances to the use of military rifles; in order for a rifle to impart the proper spin to a projectile, the projectile must fit snugly inside the barrel to engage the rifling grooves. The problem, however, was that the black powder used at that time would quickly produce a thick layer residue of fouling. After only three or four shots, a typical rifle would be impossible to reload without using a mallet to force the bullet down the fouled barrel. Delvigne's design addressed this problem by introducing a projectile that was smaller than the bore of the barrel (so more easily bypassing the accumulation of fouling) which after loading could then be struck with a ramrod. With three strokes of the ramrod, the bullet would become deformed and flatten, so as to expand in diameter against the inside of the bore, allowing the bullet to press against the rifling grooves. When fired, the bullet would accompany the rifling and spin. This improvement preserved accuracy while reducing the time required for reloading which would otherwise have been necessitated by the heavy fouling.[1]

Carabine à tige

[edit]Thouvenin's improvement involved a steel stem inside and at the center of the powder chamber, around which powder was inserted, and on top of which the bullet was dropped. When hit by the ram, the bullet expanded radially against the rifling grooves and at the same time wrapped around the stem, giving it a more efficient and aerodynamic shape.[2][3] Thouvenin published his invention in 1844.[4]

This system, although an improvement over Delvigne's method, still did not allow for a perfect engagement in the rifle, rendering the ball's trajectory rather erratic.[4] The French Army, however, adopted the improvement in 1846.[4] The Chasseurs adopted the system in 1853,[2] as did the Prussian Jägers corps,[5] where marksmen skills were essential.

The rifles were known as Thouvenin tige rifles ("carabines à tige Thouvenin"). The weapons used a 600 yards sight and a hair trigger. The barrels were rifled with eight grooves, making a turn every 36 inches.[5]

The Thouvenin rifles had the inconvenience of being very difficult to clean, especially the area around the stem.

Legacy

[edit]This development was a precursor to the invention of the Minié ball by Claude-Étienne Minié, as Thouvenin had already suggested that a bullet with a hollowed base would be most efficient.[2] Minié further developed his iron culot, with the objective of forcing the bullet outwards towards the groove through the impact of the culot against the inertia of the lead ball, in the same way as the Thouvenin stem, before even making without the culot.[2] The much simpler system superseded the Thouvenin tige gun, even allowing the transformation of any smoothbore into a powerful rifled gun ("fusil rayé"), simply by the making of rifling grooves and use of the appropriate Minié bullet available to all the troops of the line.[6]

Notes

[edit]- ^ John Gibbon, The Artillerist's Manual, p.125

- ^ a b c d John Gibbon, The Artillerist's Manual, 1860, p.135

- ^ United States Military, Military Commission to Europe in 1855 and 1856, p.221

- ^ a b c David Westwood, Rifles, p.23

- ^ a b David Westwood, Rifles, p.81

- ^ John Gibbon, The Artillerist's Manual, p.136