Hot dog

A typical hot dog with American mustard as a condiment | |

| Alternative names | Frankfurter, frank, wiener, weenie, tube steak, sausage, banger, coney |

|---|---|

| Type | Fast food, finger food |

| Place of origin |

|

| Serving temperature | Hot |

| Main ingredients | Sausage made from pork, beef, chicken, turkey or combinations thereof and a bun |

| Ingredients generally used |

|

| Variations | Multiple |

A hot dog[1][2] is a dish consisting of a grilled, steamed, or boiled sausage served in the slit of a partially sliced bun.[3] The term hot dog can refer to the sausage itself. The sausage used is a wiener (Vienna sausage) or a frankfurter (Frankfurter Würstchen, also just called frank). The names of these sausages commonly refer to their assembled dish.[4] Hot dog preparation and condiments vary worldwide. Common condiments include mustard, ketchup, relish, onions in tomato sauce, and cheese sauce. Other toppings include sauerkraut, diced onions, jalapeños, chili, grated cheese, coleslaw, bacon and olives. Hot dog variants include the corn dog and pigs in a blanket. The hot dog's cultural traditions include the Nathan's Hot Dog Eating Contest and the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile.

These types of sausages were culturally imported from Germany and became popular in the United States. It became a working-class street food in the U.S., sold at stands and carts. The hot dog has become closely associated with baseball and American culture. Although particularly connected with New York City and its cuisine, the hot dog eventually became ubiquitous throughout the US during the 20th century. Its preparation varies regionally in the country, emerging as an important part of other regional cuisines, including Chicago street cuisine.[5][6][7]

History

The word frankfurter comes from Frankfurt, Germany, where pork sausages similar to hot dogs originated.[8] These sausages, Frankfurter Würstchen, were known since the 13th century and given to the people on the event of imperial coronations, starting with the coronation of Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor, as King. "Wiener" refers to Vienna, Austria (German: Wien), home to a sausage made of a mixture of pork and beef.[9] Johann Georg Lahner, an 18th/19th century butcher from the Franconian city of Coburg, is said to have brought the Frankfurter Würstchen to Vienna, where he added beef to the mixture and simply called it Frankfurter.[10] Nowadays, in German-speaking countries, except Austria, hot dog sausages are called Wiener or Wiener Würstchen (Würstchen means "little sausage"), to differentiate them from the original pork-only mixture from Frankfurt. In Swiss German, it is called Wienerli, while in Austria the terms Frankfurter or Frankfurter Würstel are used.[citation needed]

It is not definitively known who started the practice of serving the sausage in the bun. One of the strongest claims comes from Harry M. Stevens who was a food concessionaire.[11] The claim is that, while working at the New York Polo Grounds in 1901, he came upon the idea of using small French rolls to hold the sausages when the waxed paper they were using ran out.[12][13]

A German immigrant named Feuchtwanger, from Frankfurt, in Hesse, allegedly pioneered the practice in the American Midwest; there are several versions of the story with varying details. According to one account, Feuchtwanger's wife proposed the use of a bun in 1880: Feuchtwanger sold hot dogs on the streets of St. Louis, Missouri, and provided gloves to his customers so that they could handle the sausages without burning their hands. Losing money when customers did not return the gloves, Feuchtwanger's wife suggested serving the sausages in a roll instead.[14] In another version, Antoine Feuchtwanger, or Anton Ludwig Feuchtwanger, served sausages in rolls at the World's Fair – either at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis,[15][16] or, earlier, at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, in Chicago[17] – again, allegedly because the white gloves provided to customers to protect their hands were being kept as souvenirs.[18]

Another possible origin for serving the sausages in rolls is the pieman Charles Feltman, at Coney Island in New York City. In 1867 he had a cart made with a stove on which to boil sausages, and a compartment to keep buns in which they were served fresh. In 1871 he leased land to build a permanent restaurant, and the business grew, selling far more than just the "Coney Island Red Hots" as they were known.[19][20][21]

Etymology

The term dog has been used as a synonym for sausage since the 1800s, possibly from accusations that sausage makers used dog meat in their sausages.[22]

In Germany the consumption of dog meat was common in Saxony, Silesia, Anhalt, and Bavaria during the 19th and 20th centuries.[23][24][25] Hot dogs occasionally contained it.[26]

An early use of the term hot dog in reference to the sausage-meat appears in the Evansville (Indiana) Daily Courier (September 14, 1884):

even the innocent 'wienerworst' man will be barred from dispensing hot dog on the street corner.[27]

It was used to mean a sausage in casing in the Paterson (New Jersey) Daily Press (31 December 1892):

the 'hot dog' was quickly inserted in a gash in a roll.[27]

Subsequent uses include the New Brunswick Daily Times (New Jersey; May 20, 1893), the New York World (May 26, 1893), and the Knoxville Journal (September 28, 1893).[28]

According to one story, the use of the complete phrase hot dog (in reference to sausage) was coined by the newspaper cartoonist Thomas Aloysius "Tad" Dorgan around 1900 in a cartoon recording the sale of hot dogs during a New York Giants baseball game at the Polo Grounds.[28] He may have used the term because he did not know how to spell "dachshund".[22][29] No copy of the apocryphal cartoon has ever been found.[30] Dorgan did use the term at other times; the earliest known example was in connection with a bicycle race at Madison Square Garden, appearing in The New York Evening Journal of December 12, 1906.[22][28]

General description

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

Ingredients

Common hot dog sausage ingredients include:[31]

- Meat trimmings and fat

- Flavorings, such as salt, garlic, and paprika

- Preservatives (cure) – typically sodium erythorbate and sodium nitrite

Pork and beef are the traditional meats used in hot dogs. Less expensive hot dogs are often made from chicken or turkey, using low-cost mechanically separated poultry. Changes in meat technology and dietary preferences have led manufacturers to lower the salt content and use turkey, chicken, and vegetarian meat substitutes.

Commercial preparation

Hot dogs are prepared commercially by mixing the ingredients (meats, spices, binders and fillers) in vats where rapidly moving blades grind and mix the ingredients in the same operation. This mixture is forced through tubes into casings for cooking. Most hot dogs sold in the US are "skinless" rather than "natural casing" sausages.

Natural casing

As with most sausages, hot dogs must be in a casing to be cooked. Traditional casing is made from the small intestines of sheep. The products are known as "natural casing" hot dogs or frankfurters.[32] These hot dogs have firmer texture and a "snap" that releases juices and flavor when the product is bitten.[32]

Kosher casings are expensive in commercial quantities in the US, so kosher hot dogs are usually skinless or made with reconstituted collagen casings.[32]

Skinless

"Skinless" hot dogs use a casing for cooking, but the casing may be a long tube of thin cellulose that is removed between cooking and packaging, a process invented in Chicago in 1925[33] by Erwin O. Freund, founder of Visking.[34]

The first skinless hot dog casings were produced by Freund's new company under the name "Nojax", short for "no jackets" and sold to local Chicago sausage makers.

Skinless hot dogs vary in surface texture, but have a softer "bite" than with natural casing. Skinless hot dogs are more uniform in shape and size and cheaper to make than natural casing hot dogs.

Home consumption

A hot dog may be prepared and served in various ways.[35] Typically it is served in a hot dog bun with various condiments and toppings. The sausage itself may be sliced and added, without bread, to other dishes.

-

Hot dog garnished with ketchup and onions

-

Toaster for hot dog buns that grills hot dogs at the same time

-

Hot dog at college fair

Sandwich debate

There is an ongoing debate about whether a hot dog, fully assembled in its bun with condiments, fits the description of a sandwich.[36] In 2015, the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council (NHDSC) declared that a hot dog is not a sandwich.[37][38] Hot dog eating champions Joey Chestnut and Takeru Kobayashi agree with the NHDSC,[39][40] as does the host of the contest.[38] Merriam-Webster, on the other hand, has stated that a hot dog is indeed a sandwich.[41]

United States Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg also weighed in on the matter, stating that a hot dog might be categorized as a sandwich, but ultimately it comes down to the definition of a sandwich.[42] She went on to acknowledge that a hot dog bun is a single roll that is not sliced all the way through, and in that way is similar to a submarine sandwich.[43]

In June 2022, Jon Batiste stated that hot dogs were his favourite kind of sandwiches when he was given the Colbert Questionert by Stephen Colbert.[44]

Health risks

Although hot dogs are cooked during manufacture, it is still recommended that packaged hot dogs are heated to an internal temperature of at least 165 °F (75 °C) prior to consumption.[45]

Most hot dogs are high in fat and salt and have preservatives sodium nitrate and potassium nitrate, which are contributors to nitrate-containing chemicals classified as group 1 carcinogens by the World Health Organization,[46] although this has been disputed.[47][48] These health concerns have resulted in manufacturers offering alternative product lines made from turkey and chicken, and uncured, low-sodium, and "all-natural" franks. Hot dogs have relatively low carcinogenic heterocyclic amine (HCA) levels compared to other types of ready-to-eat meat products because they are manufactured at low temperatures.[49]

An American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) report found that consuming one daily 50-gram serving of processed meat—about one hot dog—increases long-term risk of colorectal cancer by 20 percent.[50] Thus, eating a hot dog every day would increase the probability of contracting colorectal cancer from 5.8 percent to 7 percent. The AICR's warning campaign has been criticized as being "attack ads".[48][51] The Cancer Project group filed a class-action lawsuit demanding warning labels on packages and at sporting events.[52]

Like many foods, hot dogs can cause illness if not cooked properly to kill pathogens. Listeria monocytogenes, a type of bacteria sometimes found in hot dogs, can cause serious infections in infants and pregnant women, and can be transmitted to an infant in utero or after birth. Adults with suppressed immune systems can also be harmed.[53]

Due to their size, shape, and ubiquitous consumption, hot dogs present a significant choking risk, especially for children. A study in the US found that 17% of food-related asphyxiations among children younger than 10 years of age were caused by hot dogs.[54] The risk of choking on a hot dog is greatly reduced by slicing it. It has been suggested that redesign of the size, shape and texture of hot dogs would reduce the choking risk.[55]

In the United States

Hot dogs are a traditional element of American food culture, having obtained significant cultural and patriotic status from their association with public events and sports since the 1920s.[56][57] In the US, the term hot dog refers to both the sausage by itself and the combination of sausage and bun. Many nicknames applying to either have emerged over the years, including frankfurter, frank, wiener, weenie, coney, and red hot. Annually, Americans consume 20 billion hot dogs.[58]

Restaurants

Stands and trucks sell boiled hot dogs at street and highway locations. Wandering hot dog vendors sell their product in baseball parks. At convenience stores, hot dogs are kept heated on rotating grills. Hot dogs are also common on restaurants' children's menus. Costco, a big-box retail chain, sells a yearly average of 135 million hot dogs at its food courts, at a notably low price.[59] Fast-food restaurant chains typically do not carry hot dogs because of its shorter shelf-life, more complex toppings and cooking, and mismatched consumer expectations.[60] There are also restaurants where hot dogs are a specialty.

Condiments

Hot dogs are commonly served with one or more condiments. In 2005, the US-based National Hot Dog & Sausage Council (part of the American Meat Institute) found mustard to be the most popular, preferred by 32% of respondents; 23% favored ketchup; 17% chili; 9% pickle relish, and 7% onions. Other toppings include sauerkraut, mayonnaise, lettuce, tomato, cheese, and chili peppers.

Condiment preferences vary across the U.S. Southerners showed the strongest preference for chili, while Midwesterners showed the greatest affinity for ketchup.[61]

Variations

American hot dog variations often have misleading names; they are commonly named for the geographical regions that allegedly inspired them instead of the regions in which they are most popular. For example, michigan hot dogs and white hots, are popular in upstate New York, whereas Coney Island hot dogs are popular in Michigan.[62]

Sauteed bell peppers, onions, and potatoes find their way into New Jersey's deep-fried Italian hot dog. Hot wieners, or weenies, are a staple in Rhode Island where they are sold at restaurants under the misleading name "New York System."[63] Texas hot dogs are spicy variants found in upstate New York and Pennsylvania (and as "all the way dogs" in New Jersey), but not Texas. In the Philadelphia metro area, Texas Tommy refers to a hot dog variant in which the frank is topped with melted cheese (often cheddar) and wrapped in bacon. In the Midwest, the Chicago-style hot dog is served on a poppy seed bun and topped with mustard, fresh tomatoes, onions, "sport peppers", bright green relish, dill pickles, and celery salt.

The "New York dog" or "New York style" hot dog is a natural-casing all-beef frank topped with sauerkraut and spicy brown mustard, onions optional, invented and popularized in New York City.[64]

Some baseball parks have signature hot dogs, such as Dodger Dogs at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, and Fenway Franks at Fenway Park in Boston.[65][66]

Washington, D.C. is home to the half-smoke, a half beef, half pork sausage that is both grilled and smoked. A half-smoke is often placed into a hotdog-style bun and topped with chili, cheese, onions, and mustard, similar to a chili dog. Among the famous half-smoke restaurants in the Washington area include Ben's Chili Bowl, which is a cultural landmark, and Weenie Beenie in Arlington County, Virginia.

In Canada

Skinner's Restaurant, in Lockport, Manitoba, is reputed to be Canada's oldest hot dog outlet in continuous operation, founded in 1929 by Jim Skinner Sr.[67][68] Hot dogs served at Skinner's are European style foot-long (30.5 cm) hot dogs with natural casings, manufactured by Winnipeg Old Country Sausage in Winnipeg, Manitoba.[citation needed]

Outside North America

In most of the world, a "hot dog" is recognized as a sausage in a bun, but the type varies considerably. The name is often applied to something that would not be described as a hot dog in North America. For example, in New Zealand a "hot dog" is a battered sausage, often on a stick, which is known as a corn dog in North America; an "American hot dog" is the version in a bun.[69]

Gallery

-

An Austrian "hot dog" can use a hollowed-out baguette as the bread.

-

Grilled sausages on sticks for sale in Thailand

-

Hot dog sushi

-

Thai khanom Tokiao being prepared, a Thai style crêpe with a hot dog sausage, at a night market

-

Miniature hot dogs in Japan

-

Hot dog from Bæjarins Beztu Pylsur in Iceland

-

In Brazil, a cachorro-quente is served on a bread roll with a tomato-based broth, corn, and potato sticks.

-

German Hot Dog version served here in Berlin, Germany. In Germany, such sausages are heated in a kettle of hot broth, but are also often grilled, then served in a crunchy bun. The German term for this grilled street food is “Bockwurst” or ”Bratwurst im Brötchen.”

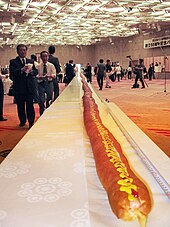

Records

The world's longest hot dog had been 60 meters (197 ft) long and rested within a 60.3-meter (198 ft) bun. The hot dog was prepared by Shizuoka Meat Producers for the All-Japan Bread Association, which baked the bun and coordinated the event, including official measurement for the world record. The hot dog and bun were the center of a media event in celebration of the Association's 50th anniversary on August 4, 2006, at the Akasaka Prince Hotel in Tokyo.[70]

On May 31, 2012, Guinness World Records certified the world record for the most expensive hot dog at USD$145.49. The "California Capitol City Dawg", served at Capitol Dawg in Sacramento, California, features a grilled 460 mm (18 in) all-beef, natural-casing frank from Chicago, served on a fresh-baked herb-and-oil focaccia roll, spread with white truffle butter, then grilled. It is topped with whole-grain mustard from France, garlic and herb mayonnaise, sauteed chopped shallots, organic mixed baby greens, maple syrup-marinated and fruitwood-smoked uncured bacon from New Hampshire, chopped tomato, moose cheese from Sweden, sweetened dried cranberries, basil olive oil and pear-cranberry-coconut balsamic vinaigrette, and ground peppercorn. Proceeds from the sale of each 1.4 kg (3 lb) super dog were donated to the Shriners Hospitals for Children.[71]

Hot dogs are a popular food for eating competitions. The record for hot dogs eaten in 10 minutes is 83 by Joey Chestnut at the "Chestnut vs. Kobayashi: Unfinished Beef" event on September 02, 2024.[72][73] The last person to hold the record before Chestnut was Takeru Kobayashi. Competitive eater Miki Sudo holds the record for most hot dogs eaten in 10 minutes by a female at 48.5 hot dogs, also setting this record on July 4, 2020.[74] The last person to hold the record before Sudo was Sonya Thomas.[75]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ "Hot Dogs Chain Store Basis". Los Angeles Times. October 11, 1925. p. 18.

- ^ Zwilling, Leonard (September 27, 1988). "Trail of Hot Dog Leads Back to 1880s". New York Times. p. A34. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ "Anniversary of Hot Dog, Bun" (PDF). Binghamton (NY) Sunday Press. November 29, 1964. p. 10D. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ Lavin, Cheryl (September 24, 1980). "Hot dog! 2 mustard moguls who relish their work". Chicago Tribune. p. E1.

- ^ Hauck-Lawson, Annie; Deutsch, Jonathan (2013). Gastropolis: Food and New York City. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231510066. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Mercuri, Becky (2007). The Great American Hot Dog Book: Recipes and Side Dishes from Across America. Gibbs Smith. ISBN 9781423600220. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Kraig, Bruce; Carroll, Patty (2012). Man Bites Dog: Hot Dog Culture in America. AltaMira Press. ISBN 9780759120747. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "frankfurter". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "wiener". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ Schmidt 2003:241

- ^ "Derby's claim to the hot dog". BBC. August 13, 2008. Archived from the original on June 8, 2022. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ Ringolsby, Tracy (March 18, 2017). "Q&A with great-great-grandson of hot dog inventor". The Official Site of Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on July 7, 2022. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ "Harry Stevens — The Hot Dog King from Niles, Ohio". Niles Historical Society. 2008. Archived from the original on September 22, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ KiteFly Web Design – kitefly.com. "Hot Dog History". Hotdogchicagostyle.com. Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- ^ Allen, Beth; Westmoreland, Susan (ed.) (2004). Good Housekeeping Great American Classics Cookbook Archived 2023-01-18 at the Wayback Machine. New York: Hearst Books. p. 49.

- ^ Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2004). Encyclopedia of Kitchen History. New York: Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 968.

- ^ McCullough 2000:240

- ^ Jakle & Sculle 1999:163–164

- ^ McCullough, Edo (1957). Good Old Coney Island: A Sentimental Journey Into the Past : the Most Rambunctious, Scandalous, Rapscallion, Splendiferous, Pugnacious, Spectacular, Illustrious, Prodigious, Frolicsome Island on Earth. Fordham Univ Press. pp. 234–236. ISBN 9780823219971. Archived from the original on January 18, 2023. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ "Coney Island History -Food & Dining". www.westland.net. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ "Charles Feltman". Coney Island History Project. May 22, 2015. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ a b c Wilton 2004:58–59

- ^ Geppert, P (October 1, 1992). "[Dog slaughtering in Germany in the 19th and 20th centuries with special consideration of the Munich area]". Berliner und Munchener tierarztliche Wochenschrift (in German). 105 (10): 335–42. PMID 1463437.

German title, "Hundeschlachtungen in Deutschland im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Raums München"

- ^ "Germany's dog meat market; Consumption of Canines and Horses Is on the Increase" (PDF). The New York Times. June 23, 1907. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2020. Retrieved January 20, 2008.

- ^ "Horse and Dog Meat as a Food in Germany". Notes. Monthly Consular and Trade Reports. 64 (240–243). United States Bureau of Manufactures, Bureau of Foreign Commerce, Dept. of Commerce; Bureau of Manufactures, Bureau of Foreign Commerce; Bureau of Statistics, Dept. of Commerce and Labor: 133. September–December 1900. Archived from the original on January 18, 2023. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "Hot Dog" Archived 2012-02-19 at the Wayback Machine at Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ a b "hot dog". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved September 10, 2017. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b c "Hot Dog (Polo Grounds myth & original monograph) barrypopik.com Archived 2011-06-08 at the Wayback Machine"

- ^ "How Did Hot Dogs Get Their Name?". Allrecipes. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ^ "Hot Dog". Snopes. July 13, 2007. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ^ "Sausage Glossary | NHDSC". www.hot-dog.org. Archived from the original on September 1, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ a b c Levine 2005:It's All in How the Dog Is Served Archived 2011-08-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zeldes, Leah A. (July 8, 2010). "Know your wiener!". Dining Chicago. Chicago's Restaurant & Entertainment Guide, Inc. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ "Viskase: About Us". Viskase Companies, Inc. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- ^ Cooper, Stacy. "Hot Dogs, Get Your Hot Dogs: all about hot dogs, wieners, franks and sausages". Inmamaskitchen.com. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- ^ Garber, Megan (November 5, 2015). "A Hot Dog Is Not a Sandwich". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ Deutsch, Lindsay (November 7, 2015). "Is a hot dog a sandwich? Council rules once and for all". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ a b Jones, Bryce (October 8, 2024). "Is a Hot Dog a Sandwich? Here's What 4 Pros Have to Say". Better Homes and Gardens. Retrieved November 6, 2024.

- ^ Chavez, Chris. "Joey Chestnut rules that a hot dog is not a sandwich". Sports Illustrated.

- ^ "Nathan's Hot Dog Eating Contest legend Kobayashi settles hot dog-sandwich debate". CBSSports.com. July 4, 2017. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "Merriam-Webster Boldly Declares That a Hot Dog is a Sandwich". www.mentalfloss.com. June 1, 2016. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ Wright, Tolly (March 22, 2018). "Stephen Colbert Gets Ruth Bader Ginsburg's Ruling on Hot Dogs v. Sandwiches". Vulture. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ "Stephen Works Out With Ruth Bader Ginsburg" Archived 2021-08-16 at the Wayback Machine, The Late Show with Stephen Colbert (2018).

- ^ Jon Batiste Takes The Colbert Questionert, June 9, 2022, archived from the original on July 8, 2022, retrieved July 8, 2022

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "How to Grill Safely". Food Safety. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on October 9, 2019. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ^ Bee Wilson (May 1, 2018). "Yes, bacon really is killing us". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- ^ "Junkfood Science: Does banning hotdogs and bacon make sense?". junkfoodscience.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- ^ a b New Attack Ad Targets Hot Dogs, Citing Dubious Cancer Risk, Fox News, August 26, 2008.

- ^ "A Hot Dog Healthier Than Chicken? Could Be..." ClickOnDetroit.com. March 23, 2011. Archived from the original on March 26, 2011. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- ^ AICR Statement: Hot Dogs and Cancer Risk Archived 2010-05-03 at the Wayback Machine, American Institute for Cancer Research, July 22, 2009.

- ^ Attack ad targets hot dogs as cancer risk, Canadian Broadcasting Company, August 27, 2008.

- ^ Hot dog cancer-warning labels sought in lawsuit: Healthy Cleveland Archived 2017-07-16 at the Wayback Machine, The Plain Dealer, August 29, 2009. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- ^ "Listeria and food safety". Health Canada. June 24, 2011. Archived from the original on May 7, 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- ^ Harris, Carole Stallings; Baker, Susan P.; Smith, Gary A.; Harris, Richard M. (May 1984). "Childhood Asphyxiation by Food: A National Analysis and Overview". JAMA. 251 (17): 2231–2235. doi:10.1001/jama.251.17.2231. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 6708272.

- ^ Szabo, Liz (February 22, 2010). "Pediatricians seek choke-proof hot dog". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 9, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Jackson, Donald Dale. "Hot Dogs Are Us". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on October 23, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ Selinger, Hannah (July 3, 2020). "How the hot dog became an American icon". Video: Diana Diroy. CNN. Archived from the original on October 23, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "In 2016, consumers spent more than $2.4 billion on hot dogs in U.S. supermarkets". National Hot Dog & Sausage Council. Archived from the original on August 22, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ Matthews, Todd (April 18, 2018). "Costco CEO Craig Jelinek on Shareholders, Costco.com, and Hot Dogs". 425Business.com/. Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ Alleyne, Allyssia (July 6, 2020). "Hot Dogs Are America's Food, So Why Aren't They a Fast-Food Staple?". Mel Magazine. Archived from the original on August 21, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ "Fire in their Bellies: Sixty Percent of Americans Prefer Hot Dogs Grilled, New Hot Dog Council Poll Data Shows Mustard Takes 'Gold Medal' in Topping Poll". National Hot Dog & Sausage Council; American Meat Institute. May 25, 2005. Archived from the original on June 16, 2005. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Bramen, Lisa. "The Annals of Geographically Confused Foods: Michigan Hot Dogs from New York". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on October 23, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ Lukas, Paul. "The Big Flavors Of Little Rhode Island." Archived 2020-11-17 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times. November 13, 2002.

- ^ TheHotDog.org (June 29, 2021). "Types of Hotdog". TheHotDog.org. Archived from the original on October 23, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "MLB Hot Dog & Sausage Guide | NHDSC". www.hot-dog.org. Archived from the original on October 23, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ Wood, Bob., Wood, Robert. Dodger Dogs to Fenway Franks: The Ultimate Guide to America's Top Baseball Parks. United States: McGraw-Hill, 1989.

- ^ "Who's got Canada's best hot dog?". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ^ "Hot dog! Skinner's celebrating 85 years". Winnipeg Sun. April 2, 2014. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ^ Rough Guides (2010). The Rough Guide to New Zealand. Rough Guides. ISBN 9780241186701.

- ^ "Guinness World Records". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- ^ Pierleoni, Allen (June 1, 2012). "Sacramento claims record with $145.49 hot dog". The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on June 4, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ^ Tucker, Josh Peter, Casey L. Moore and Heather. "Joey Chestnut vs. Kobayashi: Chestnut sets record in winning hot dog eating rematch". USA TODAY. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Joey Chestnut tops Takeru Kobayashi with new world record of 83 hot dogs to win Netflix eating battle". Yahoo Sports. September 2, 2024. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- ^ Aschwanden, Christie (July 14, 2020). "Scientists Have Finally Calculated How Many Hot Dogs a Person Can Eat at Once". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 4, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "Joey Chestnut and Miki Sudo Again Set Hot Dog Eating Records". The New York Times. July 4, 2020. Archived from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

Bibliography

- "Anniversary of Hot Dog, Bun" (PDF). Binghamton Sunday Press. Binghamton, NY. November 29, 1964. p. 10D. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- Brady, William (June 11, 1929). "Personal Health Service" (PDF). Amsterdam Evening Recorder. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- "Hot Dogs Chain Store Basis". Los Angeles Times. October 11, 1925. p. 18.

- Immerso, Michael (2002). Coney Island: The People's Playground. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3138-0.

- Jakle, John A.; Sculle, Keith A. (1999). Fast Food. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6109-3.

- Lavin, Cheryl (November 24, 1980). "Hot Dog! 2 Mustard Moguls Who Relish Their Work". The Chicago Tribune. p. E1.

- Levine, Ed (May 25, 2005). "It's All in How the Dog Is Served". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 30, 2011. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- McCollough, J. Brady (April 2, 2006). "Frankfurter, she wrote: Hot dog shrouded in mystery". The Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved May 27, 2007.

- McCullough, Edo (2000) [1957]. Good Old Coney Island: A Sentimental Journey into the Past. New York: Fordham University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-8232-1997-1.

- Schmidt, Gretchen (2003). German Pride: 101 Reasons to Be Proud You're German. New York: Citadel Press. ISBN 978-0-8065-2481-8.

- Sterngass, Jon (2001). First Resorts: Pursuing Pleasure at Saratoga Springs, Newport & Coney Island. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6586-2.

- Wilton, David (2004). Word Myths: Debunking Linguistic Urban Legends. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517284-3.

- Zwilling, Leonard (September 27, 1988). "Trail of Hot Dog Leads Back to 1880's". Opinion. The New York Times. p. A34. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

Further reading

- Hammond, Julia (July 3, 2019). "The truth about the US' most iconic food". BBC Travel.

- Loftus, Jamie (2023). Raw Dog: The Naked Truth About Hot Dogs. New York: Tor Publishing Group. ISBN 9781250847744. OCLC 1372498488.