History of the Philippines (1986–present)

Republic of the Philippines Republika ng Pilipinas | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motto: "Maka-Diyos, Maka-Tao, Makakalikasan at Makabansa" ("For God, People, Nature, and Country") | |||||||

| Anthem: Lupang Hinirang (English: "Chosen Land") | |||||||

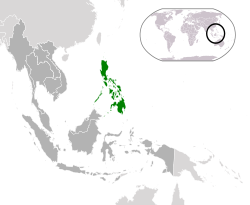

Location of the Philippines – green in ASEAN – gray | |||||||

| Capital | Manila 14°35′N 120°58′E / 14.583°N 120.967°E | ||||||

| Official languages | |||||||

| Government | Unitary presidential democratic constitutional republic | ||||||

| Bongbong Marcos | |||||||

| Sara Duterte | |||||||

| Francis Escudero | |||||||

| Martin Romualdez | |||||||

| Alexander Gesmundo | |||||||

| Legislature | Congress | ||||||

| Senate | |||||||

| House of Representatives | |||||||

| Establishment | |||||||

| February 2, 1987 (37 years ago) | |||||||

| Area | |||||||

• Total | 300,000 km2 (120,000 sq mi) | ||||||

| GDP (PPP) | • Total

Increase $1.0 trillion[10] (29th) • Per capita Increase $9,061 estimate | ||||||

• Total | • Total Increase $1.0 trillion[10] (29th? | ||||||

• Per capita | • Per capita Increase $9,061[10] (115th) | ||||||

| HDI (2019) | 0.718 high | ||||||

| Currency | Peso (Filipino: piso) (₱) (PHP) | ||||||

| ISO 3166 code | PH | ||||||

| |||||||

| History of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

This article covers the history of the current Philippine republican state following the 1986 People Power Revolution, known as the Fifth Philippine Republic.

The return of democracy and government reforms beginning in 1986 were hampered by national debt, government corruption, coup attempts, disasters, a persistent communist insurgency,[1] and a military conflict with Moro separatists.[2] During Corazon Aquino's administration, U.S. forces withdrew from the Philippines, due to the rejection of the U.S. Bases Extension Treaty,[3][4] and leading to the official transfer to the government of Clark Air Base in November 1991 and Subic Bay in December 1992.[5][6] The administration also faced a series of natural disasters, including the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in June 1991.[7][8]

After introducing a constitution that limited presidents to a single term, Aquino did not stand for re-election.[9] Aquino was succeeded by Fidel V. Ramos. During this period the country's economic performance remained modest, with a 3.6%[10] percent GDP growth rate.[11] Political stability and economic improvements, such as the peace agreement with the Moro National Liberation Front in 1996,[12] were overshadowed by the onset of the 1997 Asian financial crisis.[13][14]

Ramos' successor, Joseph Estrada assumed office in June 1998 and under his presidency the economy recovered from −0.6% growth to 3.4% by 1999.[15][16][17] The government announced a war against the Moro Islamic Liberation Front in March 2000 and attacked various insurgent camps, including their headquarters.[18][19] In the middle of ongoing conflict with the Abu Sayyaf,[20] accusations of alleged corruption, and a stalled impeachment process, Estrada was overthrown by the 2001 EDSA Revolution and he was succeeded by his Vice President, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo on January 20, 2001.[21]

In Arroyo's 9-year administration, her rule was tainted by graft and political scandals like the Hello Garci scandal pertaining to the alleged manipulation of votes in the 2004 presidential elections.[22][23][24][25] On November 23, 2009, 34 journalists and several civilians were massacred in Maguindanao.[26][27]

Benigno Aquino III won the 2010 national elections and served as the 15th president of the Philippines.[28] The Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro was signed on October 15, 2012, as the first step of the creation of an autonomous political entity named Bangsamoro.[29] However, a clash that took place in Mamasapano, Maguindanao killed 44 members of the Philippine National Police-Special Action Force and put the efforts to pass the Bangsamoro Basic Law into law in an impasse.[30][31] Tensions regarding territorial disputes in eastern Sabah and the South China Sea escalated.[32][33][34] In 2013, two more years were added to the country's ten-year schooling system for primary and secondary education.[35] In 2014 the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement, was signed, paving the way for the return of United States Armed Forces bases into the country.[36][37][38][39]

Former Davao City mayor Rodrigo Duterte won the 2016 presidential election, becoming the first president from Mindanao.[40] On July 12, 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled in favor of the Philippines in its case against China's claims in the South China Sea.[41] After winning the Presidency, Duterte launched an intensified anti-drug campaign and took steps to deal with to fulfill a campaign promise of wiping out criminality in six months.[42] As of February 2019, the death toll for the Philippine Drug War is 5,176.[43][44][45][46] In 2017, he oversaw the battle of Marawi against insurgent groups, and the rehabilitation of the city. The implementation of the Bangsamoro Organic Law led to the creation of the autonomous Bangsamoro region in Mindanao.[47][48]

Former senator Bongbong Marcos won the 2022 presidential election, 36 years after the People Power Revolution which led to his family's exile in Hawaii. He was inaugurated on June 30, 2022.[49]

Corazon Aquino administration (1986–1992)

[edit]With the People Power Revolution, Corazon Aquino's assumption into power marked the restoration of democracy in the country. Aquino immediately formed a revolutionary government to normalize the situation, and provided for a transitional "Freedom Constitution" that restored civil liberties and dismantled the heavily Marcos-ingrained bureaucracy— abolishing the Batasang Pambansa and relieving all public officials.[50]

The Aquino administration likewise appointed a constitutional commission that submitted a new permanent constitution that was ratified and enacted in February 1987.[51] The constitution crippled presidential power to declare martial law, proposed the creation of autonomous regions in the Cordilleras and Muslim Mindanao, and restored the presidential form of government and the bicameral Congress.[52]

Progress was made in revitalizing democratic institutions and respect for civil liberties, but Aquino's administration was also viewed as weak and fractious, and a return to full political stability and economic development was hampered by several attempted coups staged by disaffected members of the Philippine military.[53] Aquino privatized many of the utilities the government owned, such as water and electricity. This practice was viewed by many as Aquino catering to oligarchic as well U.S. interests, losing the government's power of regulation.

Economic growth was additionally hampered by a series of natural disasters. In June 1991, Mount Pinatubo in Central Luzon erupted, after being dormant for 600 years. It was the second largest volcanic eruption of the 20th century. It left 700 dead and 200,000 homeless, and cooled global weather by 1.5 °C (34.7 °F).[54][55][56][57]

On September 16, 1991, despite lobbying by President Aquino, the Philippine Senate rejected a treaty that would have allowed a 10-year extension of the U.S. military bases in the country. The United States turned over Clark Air Base in Pampanga to the government in November,[6] and Subic Bay Naval Base in Zambales in December 1992, ending almost a century of U.S. military presence in the Philippines.[5]

Fidel Ramos administration (1992–1998)

[edit]In the 1992 elections, Defense Secretary Fidel V. Ramos (Lakas-NUCD), endorsed by Aquino, won by just 23.6% of the vote, over Miriam Defensor Santiago (PRP), Eduardo Cojuangco, Jr. (NPC), House Speaker Ramon Mitra (LDP), former First Lady Imelda Marcos (KBL), Senate President Jovito Salonga (LP) and Vice President Salvador Laurel (NP).

Early in his administration, Ramos declared "national reconciliation" his highest priority. He legalized the Communist Party and created the National Unification Commission (NUC), chaired by lawyer Manuel C. Herrera, to lay the groundwork for talks with communist insurgents, Muslim separatists, and military rebels. In June 1994, Ramos signed into law a general conditional amnesty covering all rebel groups, and Philippine military and police personnel accused of crimes committed while fighting the insurgents. In October 1995, the government signed an agreement bringing the military insurgency to an end.

A standoff with China occurred in 1995, when the Chinese military built structures on Mischief Reef in the disputed Spratly Islands claimed by the Philippines as Kalayaan Islands.

Ramos was heavily criticized for his liberal economic policies,[58] such as passing an oil-deregulation law, thus inflating prices of gasoline products.[59] Ramos was also criticized for alleged corruption in his handling of the Philippine Centennial Exposition and the PEA-AMARI land deal, in which Ramos allegedly received kickbacks amounting to millions of pesos.[60]

A peace agreement with the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) under Nur Misuari, a major Muslim separatist group fighting for an independent Bangsamoro homeland in Mindanao, was signed in 1996, ending the 24-year-old struggle. However an MNLF splinter group, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) under Salamat Hashim continued the armed Muslim struggle for an Islamic state.

The 1998 elections were won by former movie actor and Vice President Joseph Ejercito Estrada (PMP-LAMMP) with overwhelming mass support, with close to 11 million votes. The other ten candidates included his closest rival and administration candidate, House Speaker Jose De Venecia (Lakas-NUCD-UMDP) with 4.4 million votes, Senator Raul Roco (Aksyon Demokratiko), former Cebu governor Emilio Osmeña (PROMDI) and Manila mayor Alfredo Lim (LP).

Joseph Estrada administration (1998–2001)

[edit]

Estrada assumed office amid the Asian Financial Crisis. The economy did, however, recover from it. From a low −0.6% growth in 1998 to a moderate growth of 3.4% by 1999.[61][62][63][64][65][66] Like his predecessor there was a similar attempt to change the 1987 Constitution under a process termed as CONCORD or Constitutional Correction for Development. Unlike the proposed changes under Ramos and Arroyo, the CONCORD proposal, according to its proponents, would only amend the 'restrictive' economic provisions of the constitution that are considered as impediments to the entry of more foreign investments in the Philippines. However, Estrada was not successful in amending the constitution.

On March 21, 2000, President Estrada declared an "all-out-war" against the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) after the worsening secessionist movement in Mindanao.[67][68] The government later captured 46 MILF camps including the MILF's headquarters: Camp Abubakar.[69][70][71]

In October 2000, Ilocos Sur governor Luis "Chavit" Singson, a close friend of Estrada, accused the President of receiving collections from jueteng, an illegal numbers game.

On November 13, 2000, the House of Representatives impeached Estrada on grounds of bribery, graft and corruption, betrayal of public trust and culpable violation of the constitution. His impeachment trial in the Senate began on December 7, but broke down on January 17, 2001, after 11 senators allied with Estrada successfully blocked the opening of confidential bank records that would have been used by the prosecution to incriminate the President. In response, millions of people massed up at the EDSA Shrine, where in 1986 the People Power Revolution had ousted Marcos, demanding Estrada's immediate resignation in what became known as "EDSA II". Estrada's cabinet resigned en masse and the military and police withdrew their support. On January 20, the Supreme Court of the Philippines declared the presidency vacant and swore in Vice President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo as the country's 14th President. Estrada and his family evacuated the Malacañan Palace soon after.

Nevertheless, Estrada himself stood before the Supreme Court on grounds that he did not resign, but just went on an indefinite leave. The Supreme Court upheld the legitimacy of Arroyo with finality on March 2, 2001.

Gloria Macapagal Arroyo administration (2001–2010)

[edit]

Vice President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo (the daughter of the late President Diosdado Macapagal) was sworn in as Estrada's successor on the day of his departure. Estrada and his allies later challenged the legitimacy of Arroyo's government, arguing that the transfer of power to Arroyo was unconstitutional because he did not resign from office, but the Supreme Court twice upheld Arroyo's legitimacy. After Estrada was arrested on plunder charges in April 2001, thousands of his supporters staged an "EDSA III" to demand his reinstatement through rallies, but by the early morning of May 1, the protesters marched to Malacañang Palace and attempted to storm the premises. The attempt failed when authorities arrived to quell the uprising outside Malacañang's gates. Arroyo's accession to power was further legitimated by the mid-term congressional and local elections held in May 2001, when her coalition won an overwhelming victory.[72]

Arroyo's initial term in office was marked by fractious coalition politics as well as a military mutiny in Manila in July 2003 that led her to declare a month-long nationwide state of rebellion.[72] Although she had declared in December 2002 that she would not contest the May 2004 presidential election, citing a need to heal divisiveness, she reversed herself in October 2003 and decided to run.[72] She was re-elected and sworn in for her own six-year term as president on June 30, 2004.

In 2005, a tape of a wiretapped conversation surfaced bearing the voice of Arroyo apparently asking an election official if her margin of victory can be maintained.[73] The tape sparked protests calling for Arroyo's resignation.[73] Arroyo admitted to inappropriately speaking to an election official, but denied allegations of fraud and refused to step down.[73] Attempts to impeach the president failed later that year.

Toward the end of her term, Arroyo spearheaded a controversial plan for an overhaul of the constitution to transform the present unitary and presidential republic with a bicameral legislature into a federal parliamentary government with a unicameral legislature.[74]

Benigno Aquino III administration (2010–2016)

[edit]

On June 9, 2010, at the Batasang Pambansa Complex, in Quezon City, the Congress of the Philippines proclaimed Aquino as the President-elect of the Philippines,[75] following the 2010 election with 15,208,678 votes,[76] while Jejomar Binay, the former mayor of Makati, was proclaimed as the Vice President-elect of the Philippines with 14,645,574 votes,[77] defeating runner-up for the vice presidency Mar Roxas, the standard-bearer of the Liberal Party for vice president.

The presidential transition began when Aquino won the 2010 Philippine presidential election.[76] The transition was in charge of the new presidential residence, cabinet appointments and cordial meetings between them and the outgoing administration.

On May 11, 2010, outgoing President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo signed an administrative order, creating the Presidential Transition Cooperation Team.[78] Arroyo instructed outgoing Executive Secretary Leandro Mendoza to lead the transition team.[78] The transition team was created "to ensure peaceful, orderly and [efficient] transition on the 30th of June".[78] On June 9, 2010, the transition team started informal meetings with the Aquino transition team.[79]

On June 16, 2010, Aquino organized his transition team in a letter to outgoing Presidential Management Staff Secretary Elena Bautista-Horn.[80] Aquino appointed the members of his transition team; defeated runner-up for the vice presidency Mar Roxas, incoming Executive Secretary Paquito Ochoa, Jr., former Secretary of Education Florencio Abad, former Secretary of Finance Cesar Purisima, and Julia Abad, daughter of Florencio Abad and Aquino's chief of staff.[80]

The presidential residence of Aquino is the Bahay Pangarap (English: House of Dreams),[81] located inside of Malacañang Park,[82] at the headquarters of the Presidential Security Group across the Pasig River from Malacañan Palace.[81][83] Aquino is the first president to make Bahay Pangarap his official residence.[84][85] Aquino refused to live in Malacañan Palace, the official residence of the President of the Philippines, or in Arlegui Mansion, the residence of former presidents Corazon Aquino and Fidel V. Ramos, stating that the two residences are too big,[81] and also stated that his small family residence at Times Street in Quezon City would be impractical, since it would be a security concern for his neighbors.[83]

Aquino named long-time friend, Paquito Ochoa, Jr., as Executive Secretary.[86][87] Aquino appointed Corazon Soliman as Secretary of Social Welfare & Development, a position she once held under the Arroyo administration but later resigned in 2005.[87] On June 22, 2010, Leila de Lima accepted the offer to join the cabinet and later took over the helm of the Department of Justice on July 2, 2010.[88] On July 15, 2010, Vice President Jejomar Binay was appointed as chairman of HUDCC.[89] On June 24, 2010, Br. Armin Luistro FSC, president of De La Salle University, accepted the post of Secretary of Education after meeting with the school's stakeholders.[90] On June 27, 2010, Aquino reappointed incumbent Secretary of Foreign Affairs Alberto Romulo.[91]

On June 29, 2010, Aquino officially named the members of his Cabinet, with Aquino himself as Secretary of the Interior and Local Government.[86] Aquino also announced the formation of a truth commission that will investigate various issues including corruption allegations against outgoing President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. Aquino named former Chief Justice Hilario Davide, Jr. to head the truth commission.[92]

The inauguration of President Benigno Aquino III and Vice President Jejomar Binay was held at the Quirino Grandstand in Luneta Park, Manila on June 30, 2010.[93] The oath of office was administered by Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines Conchita Carpio-Morales, who officially accepted Aquino's request to swear him into office,[94] reminiscent of the decision of his mother, who in 1986, was sworn into the presidency by Associate Justice Claudio Teehankee.[95] Aquino refused to allow Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines Renato Corona to swear him into office, due to Aquino's opposition to the appointment of Corona by outgoing President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.[96] Aquino was congratulated by the President Barack Obama of the United States, Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, and the government of Australia.[97]

In 2013, the government announced it was drawing up a new framework for potential peace talks with the New People's Army.[98]

In 2015, a clash which took place in Mamasapano, Maguindanao killed 44 members of the Philippine National Police-Special Action Force, resulting in efforts to pass the Bangsamoro Basic Law reaching an impasse.[99][100]

Rodrigo Duterte administration (2016–2022)

[edit]

Davao City mayor Rodrigo Duterte of PDP–Laban won the 2016 presidential election by a landslide, garnering 39.01% or 16,601,997 of the total votes, becoming the first Mindanaoan to become president. On the other hand, Camarines Sur 3rd District representative Leni Robredo won with the second-narrowest margin in history, against Senator Bongbong Marcos.[101] On May 30, the Congress had proclaimed Rodrigo Duterte, despite his absence, as president-elect and Leni Robredo as vice president-elect.[102]

The presidential transition of Rodrigo Duterte began when Duterte won the 2016 Philippine presidential election. The transition was in charge of the new presidential residence, cabinet appointments and cordial meetings between them and the outgoing administration.

Duterte's presidency began following his inauguration on June 30, 2016, at the Rizal Ceremonial Hall of the Malacañang Palace in Manila, which was attended by more than 627 guests.[103]

On July 12, 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled in favor of the Philippines in its case against China's claims in the South China Sea.[41] On August 1, 2016, the Duterte administration launched a 24-hour complaint office accessible to the public through a nationwide hotline, 8888, and change the nationwide emergency telephone number from 117 to 911.[104][105] By October 2016, one hundred days after Duterte took office, the death toll for the Philippine Drug War passed 3,000 people.[106] As of February 2019, the death toll for the Philippine Drug War is 5,176.[107][108][109][110]

In middle of October to November 2016, President Duterte announced numerous times his shift to ties with China and Russia. The president also blasted the United States and Barack Obama, as well as the United Nations and UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, numerous times in various live interviews and speeches while in the Philippines, Japan, Vietnam, Indonesia, Brunei, and Laos.[111][112][113][114][115][116]

On November 8, 2016, the Supreme Court of the Philippines ruled in favor of the burial of the late president and dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the Libingan ng mga Bayani, the country's official cemetery for heroes, provoking protests from various groups.[117]

Duterte initiated the "Build, Build, Build" program in 2017 that aimed to usher the Philippines into a new "golden age of infrastructure"[118] and was expected to create more jobs and business opportunities, which, in turn, would sustain the country's economic growth and accelerate poverty reduction.[119] The construction industry needs two million more workers to sustain the program.[120][121] The program is made up of numerous projects in various sectors, such as air, rail, and road transport as well as other public utilities and infrastructures.[122][123] The country is expected to spend $160 billion to $180 billion up to 2022 for the public investments in infrastructure.[124] The program has been linked to supporting recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.[125]

In 2017, Duterte signed the Universal Access to Quality Tertiary Education Act, which provides for free tuition and exemption from other fees in public universities and colleges for Filipino students, as well as subsidies for those enrolled in private higher education institutions. He also signed 20 new laws, including the Universal Health Care Act, the creation of the Department of Human Settlements and Urban Development, establishing a national cancer control program, and allowing subscribers to keep their mobile numbers for life.[126]

Duterte signed laws creating the Philippine Space Agency and the departments of housing and urban development, and migrant workers. He institutionalized a national identification system and the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program, raised the age of sexual consent to 16, criminalized child marriage, simplified the adoption process, and launched the Public Utility Vehicle Modernization Program.

Duterte initiated liberal economic reforms by amending the Foreign Investment Act of 1991 and the Public Service Act to attract foreign investors, and reformed the country's tax system by signing the Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion Law and the Corporate Recovery and Tax Incentives for Enterprises Act while raising sin taxes on non-essential goods. He took measures to eliminate corruption, red tape, and money laundering by establishing the freedom of information under the Executive branch, signing the Ease of Doing Business Act, creating the Presidential Anti-Corruption Commission, and strengthening the Anti-Money Laundering Act. In agricultural policy, he liberalized rice imports by signing the Rice Tariffication Law to stabilize rice prices, granted free irrigation to small farmers, signed the Sagip Saka Act, and created a trust fund for coconut farmers.

Duterte signed the Free Internet Access in Public Places Act. He signed the automatic enrollment of all Filipinos under the government's health insurance program through the Universal Health Care Act, signed the Philippine Mental Health Law, signed a law establishing Malasakit Centers in public hospitals, ordered the full implementation of the Reproductive Health Law, banned smoking in public places nationwide, and set a price cap on select medicines. He oversaw the COVID-19 pandemic in the country, implementing strict lockdown measures causing in 2020 a 9.5% contraction in the country's GDP, which eventually recovered to 5.6% in 2021 following gradual reopening of the economy and implementing a nationwide vaccination drive.

Duterte's domestic approval rating has been relatively high throughout his presidency.

Bongbong Marcos administration (2022–present)

[edit]In May 2022, Ferdinand Marcos Jr. (known by his nickname "Bongbong"), son of former president Ferdinand Marcos, won the presidential election by landslide. His vice presidential candidate was Sara Duterte, daughter of then-president Rodrigo Duterte.[127] On June 30, 2022, Marcos was sworn in as the Philippine president and Sara Duterte was sworn in as vice-president.[128]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Gov't drafts new framework to guide peace talks with leftist rebels". The Philippine Star. May 6, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ Alipala, Julie (October 2, 2010). "RP terror campaign cost lives of 11 US, 572 RP soldiers—military". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on February 22, 2015. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- ^ Shenon, Phillip (September 16, 1991). "Philippine Senate votes to Reject U.S. Base Renewal". The New York Times. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ De Santos, Jonathan (September 16, 2011). "Philippine Senators remember day when they rejected US bases treaty". Sun Star Manila. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ a b Whaley, Floyd (April 26, 2013). "Shadows of an Old Military Base". The New York Times. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ a b Drogin, Bob (November 27, 1991). "After 89 Years, U.S. Lowers Flag at Clark Air Base". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ^ "Tarlac map". University of Texas in Austin Library. Retrieved on August 2, 2011.

- ^ "Report of the Philippine Commission to the President, 1901 Vol. III", p. 141. Government Printing Office, Washington, 1901.

- ^ Drogin, Bob (October 20, 1989). "Aquino Bars Reelection Bid When Term Ends in 1992 : Philippines: The successor to Marcos says she will leave presidency to write her memoirs and help the poor". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ^ "Philippines Economic growth – data, chart". TheGlobalEconomy.com.

- ^ Pempel, T.J. (1999). The Politics of the Asian Economic Crisis. Cornell University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-8014-8634-0.

- ^ Gargan, Edward A. (December 11, 1997). "Last Laugh for the Philippines; Onetime Joke Economy Avoids Much of Asia's Turmoil". The New York Times. Retrieved January 25, 2008.

- ^ Sheng, Andrew (July 2009). "Financial Crisis and Global Governance: A Network Analysis" (PDF). Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ Yenilmez, Taylan & Saltoglu, Burak. "Analyzing Systemic Risk with Financial Networks During a Financial Crash" (PDF). fma.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 8, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ Maniago, E (2007). "Communication Variables Favoring Celebrity Candidates in Becoming Politicians: A Case Study of the 1998 and 2004 Elections in the Philippines". Southeast Asian Studies. 44 (4): 494–518. hdl:2433/53866.

- ^ "The Philippines: Consolidating Economic Growth". Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. March 13, 2000. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ "Records prove Estrada's achievements". Philippine Daily Inquirer. October 7, 2008. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ "Speech of Former President Estrada on the GRP-MORO Conflict". Philippine Human Development Network. September 18, 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ "Philippine Military Takes Moro Headquarters". People's Daily. July 10, 2000. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ "2 US Navy men, 1 Marine killed in Sulu land mine blast". GMA News. September 29, 2009. Archived from the original on October 2, 2009. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

Two US Navy personnel and one Philippine Marine soldier were killed when a land mine exploded along a road in Indanan, Sulu Tuesday morning, an official said. The American fatalities were members of the US Navy construction brigade, Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) spokesman Lt. Col. Romeo Brawner Jr. told GMANews.TV in a telephone interview. He did not disclose the identities of all three casualties.

and

Pessin, Al (September 29, 2009). "Pentagon Says Troops Killed in Philippines Hit by Roadside Bomb". Voice of America. Retrieved January 12, 2011.[permanent dead link] and

"Troops killed in Philippines blast". Al Jazeera. September 29, 2009. Archived from the original on October 3, 2009. Retrieved September 29, 2009. and

Gomez, Jim (September 29, 2009). "2 US troops killed in Philippines blast". CBS News. Archived from the original on February 2, 2011. Retrieved January 12, 2011. - ^ Dirk J. Barreveld (2001). Philippine President Estada Impeached!: How the President of the World's 13th Most Populous Country Stumbles Over His Mistresses, a Chinese Conspiracy and the Garbage of His Capital. iUniverse. p. 476. ISBN 978-0-595-18437-8.

- ^ "Bolante Faces Off with Senators Over Fertilizer Fund Scam". ANC. November 13, 2008. Archived from the original on March 2, 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2008.

- ^ "Arroyo claims hollow victory" by Leslie Davis, Asia Times Online, September 27, 2005.

- ^ Dizon, David. "Corruption was Gloria's biggest mistake: survey". ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- ^ "Philippines charges Gloria Arroyo with corruption". The Guardian. Associated Press. November 18, 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

Former president is formally accused of electoral fraud after government rushed to court as she tried to leave country

- ^ Jimenez-Gutierrez, Jason (November 23, 2010). "Philippines mourns massacre victims". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 27, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- ^ Perez, Analyn (November 25, 2009). "The Ampatuan Massacre: a map and timeline". GMA News. GMANews.TV.

- ^ Artemio R. Guillermo (2012). Historical Dictionary of the Philippines. Scarecrow Press. p. 39. ISBN 9780810872462.

- ^ "Speech of President Benigno Aquino III during the signing of the Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro, October 15, 2012". Official Gazette. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ "At least 30 elite cops killed in clash with MILF". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ^ Arcon, Dennis (January 26, 2015). "PNP-SAF casualties in encounter now 50 – ARMM police chief". Interaksyon. Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- ^ "The Republic of the Philippines v. The People's Republic of China". Pca-cpa.org. Archived from the original on June 27, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ^ Del Cappar, Michaela (April 25, 2013). "ITLOS completes five-man tribunal that will hear PHL case vs. China". GMA News One. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ^ Frialde, Mike (February 23, 2013). "Sultanate of Sulu wants Sabah returned to Phl". The Philippine Star. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "Aquino signs K–12 bill into law". Rappler. May 15, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ "Obama to stay overnight in PH". Rappler. April 1, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ "US, PH reach new defense deal". ABS-CBN News. April 27, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ "Philippines, US sign defense pact". Agence France-Presse. ABS-CBN News. April 28, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ Postrado, Leonard (January 13, 2016). "EDCA prevails". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ "Duterte, Robredo win 2016 polls". ABS-CBN. May 27, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ a b Philips, T.; Holmes, O.; Bowcott, O. (July 12, 2016). "Philippines wins South China Sea case against China". The Guardian. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ^ "Duterte sworn in as Philippines president". Reuters. June 30, 2016. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ "Between Duterte and a death squad, a Philippine mayor fights drug-war violence". Reuters. March 16, 2017.

- ^ "Cayetano: PH war on drugs exaggerated by fake news". ABS-CBN. May 5, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ^ "5,000 killed and 170,000 arrested in war on drugs: police | ABS-CBN News". March 29, 2019. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ "Death toll in Duterte drug war up to 5,176 – Real Numbers PH". The Manila Times Online. February 28, 2019. Archived from the original on May 19, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ Unson, John (January 27, 2019). "Plebiscite in Mindanao: Will it be the last?". The Philippine Star. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ Arguillas, Carolyn. "Bangsamoro law ratified; how soon can transition from ARMM to BARMM begin?". MindaNews. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Buan, Lian. "36 years after ousting Marcos, Filipinos elect son as president". Rappler. Rappler. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ Agoncillo, Teodoro C. (1990) [1960]. History of the Filipino People (8th ed.). Quezon City: Garotech Publishing. p. 585. ISBN 971-8711-06-6.

- ^ Agoncillo, History of the Filipino People, p. 586

- ^ "Background Notes: Philippines, November 1996". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 16, 2006.

- ^ "Then & Now: Corazon Aquino". CNN. Retrieved August 16, 2006.

- ^ "Pinatubo – Eruption Features". National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved August 23, 2006.

- ^ Drogin, Bob (August 11, 1991). "UNDER THE VOLCANO : As Mt. Pinatubo Continues to Spew Tons of Ash and Rock, Filipinos Wonder How Their Battered Country Will Ever Recover". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 27, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

President Corazon Aquino's government is overwhelmed by broken bridges, buried homes and lost crops.

- ^ "Proclamation No. 739, s. 1991". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. June 16, 1991. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Reilly, Benjamin (January 22, 2009). Disaster and Human History: Case Studies in Nature, Society and Catastrophe. McFarland. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-7864-3655-2. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Fletcher, Matthew; Lopez, Antonio. "THE LOPEZ DYNASTY". CNN. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

Many complain that under President Fidel Ramos's liberal economic policies, entrenched business clans have been tightening their hold on major industries.

- ^ Thomson, Elspeth; Chang, Youngho; Lee, Jae-Seung (2011). Energy Conservation in East Asia: Towards Greater Energy Security. World Scientific. p. 272. ISBN 978-981-277-177-3. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ Bracking, S. (November 28, 2007). Corruption and Development: The Anti-Corruption Campaigns. Springer. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-230-59062-5. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ Antonio C. Abaya, GMA’s successes, The Manila Standard, January 17, 2008

- ^ Philippines' GDP grows 3.2 pc in 1999, GNP up 3.6 pc, Asian Economic News, January 31, 2000

- ^ Philippines' GDP up 4.5% in 2nd qtr, Asian Economic News, September 4, 2000

- ^ Governor Rafael Buenaventura, The Philippines: Sustaining Economic Growth Momentum In A Challenging Global Environment Archived May 18, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, Bangko Sentral Ng Pilipinas, June 27, 2008

- ^ THE PHILIPPINES: CONSOLIDATING ECONOMIC GROWTH, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, March 13, 2000

- ^ Asian Development Outlook 2001 : II. Economic Trends and Prospects in Developing Asia : Southeast Asia Archived June 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Asian development Bank

- ^ Speech of Former President Estrada on the GRP-MORO Conflict, Human development Network, September 18, 2008

- ^ In the Spotlight: Moro Islamic Liberation Front Archived September 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, CDI Terrorism Project, February 15, 2002

- ^ Speech of Former President Estrada on the GRP-MORO Conflict, Human development Network, September 18, 2008,

- ^ Philippine Military Takes Moro Headquarters, People's Daily, July 10, 2000

- ^ Mike Banos, AFP-MILF 2000 War in Mindanao Remembered Archived March 8, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, American Chronicle, April 13, 2006

- ^ a b c "Country Profile: Philippines, March 2006" (PDF). U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved August 22, 2006.

- ^ a b c "Gloria Macapagal Arroyo Talkasia Transcript". CNN. Retrieved July 29, 2006.

- ^ Dalangin-Fernandez, Lira (July 27, 2006). "People's support for Charter change 'nowhere to go but up'". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on July 27, 2006. Retrieved July 27, 2006.

- ^ "Aquino promises justice as Philippines president – Yahoo! News". Archived from the original on June 15, 2010.

- ^ a b "Congress final tallies". newsinfo.inquirer.net. June 8, 2010. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014.

- ^ "Final tally: Binay leads Roxas by 700,000 votes". ABS-CBN News.

- ^ a b c "Arroyo assures smooth transition". Archived from the original on March 7, 2015.

- ^ "Malacañang starts transition process with Noynoy camp". ABS-CBN News.

- ^ a b "Aquino taps Roxas for transition team". Archived from the original on March 7, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Bahay Pangarap: Aquino's future home?". ABS-CBN News.

- ^ "How was PNoy's first night at Bahay Pangarap?". GMA News Online.

- ^ a b "Noynoy's new home is Bahay Pangarap". The Philippine STAR. Archived from the original on December 9, 2012.

- ^ "Bahay Pangarap for P-Noy ready". The Philippine STAR. Archived from the original on December 9, 2012.

- ^ "Briefer on Bahay Pangarap and Malacañang Park".

- ^ a b Ager, Maila (June 29, 2010). "Aquino names Cabinet, takes DILG helm". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 30, 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- ^ a b "Aquino names long-time friend as executive secretary". newsinfo.inquirer.net. May 31, 2010. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014.

- ^ Cruz, RG. "De Lima accepts offer to join Aquino Cabinet". ABS-CBN News.

- ^ "VP Binay is new housing czar". ABS-CBN News.

- ^ Malipot, Ina-Hernando (June 24, 2010). "Luistro accepts DepEd post". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on June 28, 2010. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- ^ Cabacungan, Gil Jr. (June 27, 2010). "Aquino retains Romulo as foreign affairs chief". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 30, 2010. Retrieved June 27, 2010.

- ^ "Davide named Truth Commission chief – INQUIRER.net, Philippine News for Filipinos". Archived from the original on June 30, 2010.

- ^ Esguerra, Christian (June 11, 2010). "Transition team seeks Arroyo-Aquino limo ride". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- ^ "Lady justice to administer Aquino oath – INQUIRER.net, Philippine News for Filipinos". Archived from the original on October 12, 2014.

- ^ "Trivia on Aquino and Binay". ABS-CBN News.

- ^ "No Corona-tion for Noynoy". INQUIRER.net. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015.

- ^ Queen Elizabeth II, other foreign leaders hail Aquino (June 30, 2010), Manila Bulletin (archived from the original on June 29, 2012)

- ^ "Gov't drafts new framework to guide peace talks with leftist rebels". The Philippine Star. May 6, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ "At least 30 elite cops killed in clash with MILF". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ^ Arcon, Dennis (January 26, 2015). "PNP-SAF casualties in encounter now 50 – ARMM police chief". Interaksyon. Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- ^ "Duterte, Robredo win 2016 polls". ABS-CBN. May 27, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ "Congress proclaims Duterte, Robredo as new President, VP; Rody a no-show". Inquirer.net. May 27, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ Rañada, Pia (June 22, 2016). "Duterte inauguration guest list now has 627 names". Rappler. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ Corrales, Nestor (July 7, 2016). "Duterte administration to launch 24-hour hotline in August". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- ^ "Dial 8888, 911: Gov't opens complaints, emergency hotlines". ABS CBN News. August 1, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ "IN NUMBERS: The Philippines' 'war on drugs'". Rappler.

- ^ "Between Duterte and a death squad, a Philippine mayor fights drug-war violence". Reuters. March 16, 2017.

- ^ "Cayetano: PH war on drugs exaggerated by fake news". ABS-CBN. May 5, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ^ "5,000 killed and 170,000 arrested in war on drugs: police | ABS-CBN News". March 29, 2019. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ "Death toll in Duterte drug war up to 5,176 – Real Numbers PH". The Manila Times Online. February 28, 2019. Archived from the original on May 19, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ "Philippines' Duterte in China announces split with US". www.aljazeera.com.

- ^ "Duterte aligns Philippines with China, says U.S. has lost". Reuters. October 20, 2016 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ Katie Hunt; Matt Rivers; Catherine E. Shoichet. "Philippines: Did Duterte's China gamble pay off?". CNN.

- ^ Culbertson, Alix (November 28, 2016). "Philippines president keen to forge close ties with Russia and China – but NOT the US". Express.co.uk.

- ^ Boot, Max. "Duterte's Flip-Flop Into Bed With China Is a Disaster for the United States".

- ^ "'Time to say goodbye,' Duterte tells US during visit to China". globalnation.inquirer.net. Agence France-Presse.

- ^ "Anti-Marcos protesters brave rains to condemn burial – The Manila Times". The Manila Times. November 26, 2016.

- ^ Cook, Malcolm; Singh, Daljit (April 22, 2020). Southeast Asian Affairs 2020. ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. p. 279. ISBN 978-981-4881-31-9. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ "Infra spending to sustain high growth, generate economic multipliers". Department of Finance. August 28, 2017. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ Mogato, Anna Gabriela A. (October 26, 2017). "Construction worker shortage 'about 2.5M' – DTI". BusinessWorld Online. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ Gonzales, Anna Leah E. (August 28, 2017). "2M more workers needed for 'Build Build Build'". The Manila Times. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ Schnabel, Chris (December 20, 2017). "Metro Manila Subway leads expected infra buildup in 2018". Rappler. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ^ "Recommended List of Projects for Inclusion in the Infrastructure Flagship Program" (PDF). ABS-CBN News. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ "Making "Build, Build, Build" Work in the Philippines". Asian Development Bank. October 30, 2017. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ^ Vera, Ben O. de (August 6, 2020). "Build, Build, Build's 'new normal': 13 projects added, 8 removed". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on August 17, 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ Kabiling, Genalyn (February 19, 2019). "We can keep our mobile numbers for life; Duterte signs 19 other laws". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on February 19, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ "Ferdinand Marcos Jr wins landslide election victory in the Philippines". France 24. May 9, 2022.

- ^ "Ferdinand Marcos Jr sworn in as Philippines president, replacing Duterte". BBC News. June 30, 2022.

External links

[edit]- Official government portal of the Republic of the Philippines Archived June 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Visiting Forces Agreement Full text document of the Visiting Forces Agreement signed by the Philippines and United States of America

- Counterpart Agreement Agreement between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Republic of the Philippines regarding the Treatment of Republic of the Philippines Personnel Visiting the United States of America