European Union competition law

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2015) |

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

In the European Union, competition law promotes the maintenance of competition within the European Single Market by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies to ensure that they do not create cartels and monopolies that would damage the interests of society.

European competition law today derives mostly from articles 101 to 109 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), as well as a series of Regulations and Directives. Four main policy areas include:

- Cartels, or control of collusion and other anti-competitive practices, under article 101 TFEU.

- Market dominance, or preventing the abuse of firms' dominant market positions under article 102 TFEU.

- Mergers, control of proposed mergers, acquisitions and joint ventures involving companies that have a certain, defined amount of turnover in the EU, according to the European Union merger law.[1]

- State aid, control of direct and indirect aid given by Member States of the European Union to companies under TFEU article 107.

Primary authority for applying competition law within the European Union rests with European Commission and its Directorate General for Competition, although state aids in some sectors, such as agriculture, are handled by other Directorates General. The Directorates can mandate that improperly-given state aid be repaid, as was the case in 2012 with Malev Hungarian Airlines.[2]

Leading ECJ cases on competition law include Consten & Grundig v Commission and United Brands v Commission. See also List of European Court of Justice rulings#Competition for other cases.

History

[edit]"people of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices. It is impossible indeed to prevent such meetings, by any law which either could be executed, or would be consistent with liberty and justice. But though the law cannot hinder people of the same trade from sometimes assembling together, it ought to do nothing to facilitate such assemblies; much less to render them necessary."

A Smith, Wealth of Nations (1776) Book I, ch 10

One of the paramount aims of the founding fathers of the European Community—statesmen around Jean Monnet and Robert Schuman—was the establishment of a Single Market. To achieve this, a compatible, transparent and fairly standardised regulatory framework for Competition Law had to be created. The constitutive legislative act was Council Regulation 17/62[3] (now superseded). The wording of Reg 17/62 was developed in a pre Van Gend en Loos period in EC legal evolution, when the supremacy of EC law was not yet fully established. To avoid different interpretations of EC Competition Law, which could vary from one national court to the next, the commission was made to assume the role of central enforcement authority.

The first major decision under Article 101 (then Article 85) was taken by the Commission in 1964.[4] They found that Grundig, a German manufacturer of household appliances, acted illegally in granting exclusive dealership rights to its French subsidiary. In Consten & Grundig [1966] the European Court of Justice upheld the commission's decision, expanded the definition of measures affecting trade to include "potential effects",[citation needed] and generally anchored its key position in Competition Law enforcement alongside the commission. Subsequent enforcement of Article 101 of the TFEU Treaty (combating anti-competitive business agreements) by the two institutions has generally been regarded as effective. Yet some analysts assert that the commission's monopoly policy (the enforcement of Art 102) has been "largely ineffective",[5] because of the resistance of individual Member State governments that sought to shield their most salient national companies from legal challenges. The commission also received criticism from the academic quarters. For instance, Valentine Korah, an eminent legal analyst in the field, argued that the commission was too strict in its application of EC Competition rules and often ignored the dynamics of company behaviour, which, in her opinion, could actually be beneficial to consumers and to the quality of available goods in some cases.

Nonetheless, the arrangements in place worked fairly well until the mid-1980s, when it became clear that with the passage of time, as the European economy steadily grew in size and anti-competitive activities and market practices became more complex in nature, the commission would eventually be unable to deal with its workload.[6] The central dominance of the Directorate-General for Competition has been challenged by the rapid growth and sophistication of the National Competition Authorities (NCAs) and by increased criticism from the European courts with respect to procedure, interpretation and economic analysis.[7] These problems have been magnified by the increasingly unmanageable workload of the centralised corporate notification system. A further reason why a reform of the old Regulation 17/62 was needed, was the looming enlargement of the EU, by which its membership was to expand to 25 by 2004 and 27 by 2007. Given the still developing nature of the east-central European new market economies, the already inundated Commission anticipated a further significant increase in its workload.

To all these challenges, the commission has responded with a strategy to decentralise the implementation of the Competition rules through the so-called Modernisation Regulation. EU Council Regulation 1/2003[8] places National Competition Authorities and Member State national courts at the heart of the enforcement of Articles 101 and 102. Decentralised enforcement has for long been the usual way for other EC rules, Reg 1/2003 finally extended this to Competition Law as well. The Commission still retained an important role in the enforcement mechanism, as the co-ordinating force in the newly created European Competition Network (ECN). This Network, made up of the national bodies plus the commission, manages the flow of information between NCAs and maintains the coherence and integrity of the system. At the time, Competition Commissioner Mario Monti hailed this regulation as one that will 'revolutionise' the enforcement of Articles 101 and 102. Since May 2004, all NCAs and national courts are empowered to fully apply the Competition provisions of the EC Treaty. In its 2005 report,[specify] the OECD lauded the modernisation effort as promising, and noted that decentralisation helps to redirect resources so the DG Competition can concentrate on complex, Community-wide investigations. Yet most recent developments shed doubt on the efficacy of the new arrangements. For instance, on 20 December 2006, the Commission publicly backed down from 'unbundling' French (EdF) and German (E.ON) energy giants, facing tough opposition from Member State governments. Another legal battle is currently ongoing over the E.ON-Endesa merger, where the commission has been trying to enforce the free movement of capital, while Spain firmly protects its perceived national interests. It remains to be seen whether NCAs will be willing to challenge their own national 'champion companies' under EC Competition Law, or whether patriotic feelings prevail. Many favour ever more uniformity in the interpretation and application of EU competition norms and the procedures to enforce them under this system.[9] However, when there are such differences in many Member States' policy preferences and given the benefits of experimentation, in 2020 one might ask whether more diversity (within limits) might not produce a more efficient, effective and legitimate competition regime.[10]

Mergers and abuse of dominance

[edit]Scope of competition law

[edit]Because the logic of competition is most appropriate for private enterprise, the core of EU competition regulation targets profit making corporations. This said, regulation necessarily extends further and in the TFEU, both articles 101 and 102 use the ambiguous concept of "undertaking" to delimit competition law's reach. This uncomfortable English word, which is essentially a literal translation of the German word "Unternehmen", was discussed in Höfner and Elser v Macrotron GmbH.[11] The European Court of Justice described "undertaking" to mean any person (natural or legal) "engaged in an economic activity", which potentially included state run enterprises in cases where they pursued economic activities like a private business. This included a state run employment agency, where it attempted to make money but was not in a position to meet demand. By contrast, in FENIN v Commission, public services which were run on the basis of "solidarity" for a "social purpose" were said to be outside the scope of competition law.[12] Self-employed people, who are in business on their own account, will be classed as undertakings, but employees are wholly excluded. Following the same principle that was laid down by the US Clayton Act 1914, they are by their "very nature the opposite of the independent exercise of an economic or commercial activity".[13] This means that trade unions cannot be regarded as subject to competition law, because their central objective is to remedy the inequality of bargaining power that exists in dealing with employers who are generally organised in a corporate form.

- FNV Kunsten Informatie en Media v Staat der Nederlanden (2014) C-413/13

- Viho Europe BV v Commission (1996) C-73/95 P [1996] ECR I-5457

- Societe Technique Miniere v Maschinenbau Ulm GmbH [1996] ECR 234

- Javico International and Javico AG v Yves Saint Laurent Parfums SA [1998] ECR I-1983

- Wouters v Algemene Raad van de Nederlandse Orde van Advocaten (2002) C-309/99, [2002] ECR I-1577

- Meca-Medina and Majcen v Commission [2006] ECR I-6991, C 519/04 P

Mergers and acquisitions

[edit]According to Article 102 TFEU, the European Commission has the power to regulate behaviour of large firms it claims to be abusing their dominant position or market power, as well as, preventing firms from gaining the position within the market structure that enables them to behave abusively in the first place. Mergers that have a "community dimension" are governed by the Merger Regulation (EC) No.139/2004, all "concentrations" between undertakings are subject to approval by the European Commission.

A true merger, under to competition law, is where two separate entities merger into an entirely new entity, or where one entity acquires all, or a majority of, the shares of another entity, and is able to have control over that entity.[14] Notable examples could include Ciba-Geigy and Sandoz merging to form Novartis,[15] as well as Dow Chemical and DuPont merging to form DowDuPont.[16]

Mergers can take a place on a number of basis. For example, a horizontal merger is where a merger takes place between two competitors in the same product and geographical markets and at same level of the production. A vertical merger is where mergers between firms that operate between firms that operate at different levels of the market. A conglomerate merger is merger between two strategically unrelated firms.[17]

Under the original EUMR, according to Article 2(3), for a merger to be declared compatible with the common market, it must not create or strengthen a dominant position where it could affect competition,[18] thus the central provision under EU law ask whether a concentration would if it went ahead would "significantly impede effective competition…".[19] Under Article 3(1), a concentration means a "change of control on a lasting basis results from (a) the merger of two or more previously independent undertakings… (b) the acquisition…if direct or indirect control of the whole or parts of one or more other undertakings".[20] In the original EUMR, dominance played a key role in deciding whether competition law had been infringed.[21] However, in France v. Commission, it was established by the European Court of Justice, that EUMR also apply to collective dominance, this is also where the concept of collective dominance was established.[22]

According to Genccor Ltd v. Commission,[23] the Court of First Instance stated the purpose of merger control is "…to avoid the establishment of market structures which may create or strengthen a dominant position and not need to control directly possible abuses of dominant positions". Meaning that the purpose for oversight over economic concentration by the states are to prevent abuses of dominant position by undertakings. Regulations of mergers and acquisition is meant to prevent this problem, before the creation of a dominant firm through mergers and/or acquisitions.

In recent years, mergers have increased in their complexity, size and geographical reach,[24] as seen in the merger between Pfizer and Warner-Lambert.[25] According to Merger Regulation No.139/2004,[26] for these regulations to apply, a merger must have a "community dimension", meaning the merger must have a noticeable impact within the EU, therefore the undertakings in question must have a certain degree of business within the EU common market.[27] However, in Genccor Ltd v. Commission, the Court of First Instance(now the General Court) stated that it does not matter where the merger takes place, as long as it has an impact within the community, the regulations will apply.

Through "economics links",[28] a new market can become more conductive to collusion. A transparent a market has a more concentrated structure, meaning firms can co-ordinate their behaviour with relative ease, firms can deploy deterrents and shield themselves form a reaction by their competitors and consumers.[29] The entry of new firms to the market, and any barriers that they might encounter should be considered.[30] In Airtours plc v. Commission, although the commission's decision here was annulled by the CFI, the case raised uncertainties, as it identifies a non-collusive oligopoly gap in EUMR.

Due to the uncertainty raised by the decision in Airtours v. Commission, it is suggested that an alternative approach to the problem raised in the case would be to ask whether the merger in question would "substantially lessen Competition" (SLC).[31] According to the Roller De La Mano article, the new test does not insist on dominance being necessary or sufficient, arguing that under the old law, there was underenforcement, a merger can have serious anti-competitive effect even without dominance.[32]

However, there exist certain exemptions under Article 2 EUMR, where anti-competitive conduct may be sanctioned, in the name of "technical and economic progress,[33] as well as the "failing firm" defence.[34] Although the European Commission is less concerned with mergers taking place vertically, it has taken an interest in the effects of conglomerate mergers.[35]

Abuse of dominance

[edit]Article 102 is aimed at preventing undertakings that have a dominant market position from abusing that position to the detriment of consumers. It provides that,

"Any abuse by one or more undertakings of a dominant position within the common market or in a substantial part of it shall be prohibited as incompatible with the common market insofar as it may affect trade between Member States.

This can mean

(a) directly or indirectly imposing unfair purchase or selling prices or other unfair trading conditions;

(b) limiting production, markets or technical development to the prejudice of consumers;

(c) applying dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties, thereby placing them at a competitive disadvantage;

(d) making the conclusion of contracts subject to acceptance by the other parties of supplementary obligations which, by their nature or according to commercial usage, have no connection with the subject of such contracts."

The provision aims to protect competition and promote consumer welfare by preventing firms from abusing dominant market positions. This objective has been emphasized by EU institutions and officials on numerous occasions – for example, it was stated as such during the judgement in Deutsche Telekom v Commission,[36] whilst the former Commissioner for Competition, Neelie Kroes, also specified in 2005 that: "First, it is competition, and not competitors, that is to be protected. Second, ultimately the aim is to avoid consumer harm".[37]

Additionally, the European Commission published its Guidance on Article [102] Enforcement Priorities,[38] which details the body's aims when applying Article 102, reiterating that the ultimate goal is the protection of the competitive process and the concomitant consumer benefits that are derived from it.[38]: Paras. [5–6] This Guidance was amended in 2023, when the European Commission announced its intention to adopt Guidelines on exclusionary abuses under Article 102 TFEU in 2025. When the Guidelines will be adopted, the European Commission will withdraw the Guidance on Enforcement Priorities.[39]

Notwithstanding the objectives stated above, Article 102 is quite controversial and has been much scrutinized.[40] In large part, this stems from the fact that the provision applies only where dominance is present; meaning a firm that is not in a dominant market position could legitimately pursue competitive practices – such as bundling – that would otherwise constitute abuse if committed by a dominant firm. That is not to suggest that it is unlawful for a firm to hold a dominant position; rather, it is the abuse of that position that is the concern of Article 102 – as was stated in Michelin v Commission[41] a dominant firm has a "special responsibility not to allow its conduct to impair undistorted competition".[41]: [57]

In applying Article 102, the Commission must consider two points. Firstly, it is necessary to show that an undertaking holds a dominant position in the relevant market and, secondly, there must be an analysis of the undertaking's behavior to ascertain whether it is abusive. Determining dominance is often a question of whether a firm behaves "to an appreciable extent independently of its competitors, customers and ultimately of its consumer".[42] Under EU law, very large market shares raise a presumption that a firm is dominant,[43] which may be rebuttable.[44] If a firm has a dominant position, because it has beyond a 39.7% market share,[45] then there is "a special responsibility not to allow its conduct to impair competition on the common market"[46] Same as with collusive conduct, market shares are determined with reference to the particular market in which the firm and product in question is sold.

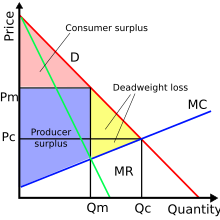

With regard to abuse, it is possible to identify three different forms that the EU Commission and Courts have recognized.[47] Firstly, there are exploitative abuses, whereby a dominant firm abuses its market position to exploit consumers – for example by reducing output and increasing the price of its goods or services.[48] Secondly, there are exclusionary abuses, involving behavior by a dominant firm which is aimed at, or has the effect of, preventing the development of competition by excluding competitors.[49] Finally, there exists a possible third category of single market abuse, which concerns behavior that is harmful to the principles of the single market more broadly, such as the impeding of parallel imports or limiting of intra-brand competition.[50]

Although there is no rigid demarcation between these three types, Article 102 has most frequently been applied to forms of conduct falling under the heading of exclusionary abuse. Generally, this is because exploitative abuses are perceived to be less invidious than exclusionary abuses because the former can easily be remedied by competitors provided there are no barriers to market entry, whilst the latter require more authoritative intervention.[51] Indeed, the commission's Guidance explicitly recognizes the distinction between the different types of abusive conduct and states that the Guidance is limited to examples of exclusionary abuse.[52] As such, much of the jurisprudence of Article 102 concerns behavior which can be categorized as exclusionary.

The Article does not contain an explicit definition of what amounts to abusive conduct and the courts have made clear that the types of abusive conduct in which a dominant firm may engage is not closed.[53] However, it is possible to discern a general meaning of the term from the jurisprudence of the EU courts. In Hoffman-La Roche, it was specified that dominant firms must refrain from 'methods different from those which condition normal competition'.[54]: Para [91] This notion of 'normal' competition has developed into the idea of 'competition on the merits',[36] which states that competitive practices leading to the marginalization of inefficient competitors will be permissible so long as it is within the realm of normal, or on the merit, competitive behavior.[55] The Commission provides examples of normal, positive, competitive behavior as offering lower prices, better quality products and a wider choice of new and improved goods and services.[56] From this, it can be inferred that behavior that is abnormal – or not 'on the merits' – and therefore amounting to abuse, includes such infractions as margin squeezing, refusals to supply and the misleading of patent authorities.[57]

Some examples of the types of conduct held by the EU Courts to constitute abuse include:

- Exclusive dealing agreements,[58] whereby a customer is required to purchase all or most of a particular type of good or service from a dominant supplier and is prevented from buying from others.

- Granting of exclusivity rebates,[59] purported loyalty schemes that are equivalent in effect to exclusive dealing agreements.

- Tying one product to the sale of another,[60] thereby restricting consumer choice.

- Bundling, similar to tying,[61] whereby a supplier will only supply its products in a bundle with one or more other products.

- Margin squeezing:[36] vertical practices which have the effect of excluding downstream competitors.

- Refusing to license intellectual property rights,[62] whereby a dominant firm holding patented rights refuses to license those rights to others.

- Refusing to supply a competitor with a good or service,[63] often in a bid to drive them out of the market.

- Predatory pricing,[64] where a dominant firm deliberately reduces prices to loss-making levels to force competitors out of the market.

- Price discrimination,[65] arbitrarily charging some market participants higher prices that are unconnected to the actual costs of supplying the goods or services.

- leveraging a dominant position by way of self-preferencing,[66] although the terminology and exact scope of the abuse is still being determined.

Whilst there are no statutory defences under Article 102, the Court of Justice has stressed that a dominant firm may seek to justify behaviour that would otherwise constitute abuse, either by arguing that the behaviour is objectively justifiable or by showing that any resulting negative consequences are outweighed by the greater efficiencies it promotes.[67][68] In order for behaviour to be objectively justifiable, the conduct in question must be proportionate[69] and would have to be based on factors external to the dominant undertaking's control,[70] such as health or safety considerations.[71] To substantiate a claim on efficiency grounds, the commission's Guidance states that four cumulative conditions must be satisfied:[72]

- The efficiencies would have to be realised, or be likely to be realised, as a result of the conduct;

- The conduct would have to be indispensable to the realisation of those efficiencies;

- The efficiencies would have to outweigh any negative effects on competition and consumer welfare; And

- The conduct must not eliminate all effective competition.

If an abuse of dominance is established, the commission has the power, pursuant to Article 23 of Regulation 1/2003, to impose a fine and to order the dominant undertaking to cease and desist from the unlawful conduct in question. Additionally, though yet to be imposed, Article 7 of Regulation 1/2003 permits the commission, where proportionate and necessary, to order the divestiture of an undertaking's assets.[73]

Examples of mergers prevented by the European Commission

[edit]The EU test is the tool by which the European Commission judges the validity of a merger. If a company attains a significant strengthening of its dominant position in the market due to the merger, the European Commission is allowed to prevent the merger between the two firms.[74]

- In 2001, the EU blocked the proposed merger between General Electric and Honeywell, although it has already been cleared by the American authorities. The reasoning of the European Commission was that the merger would significantly impede the competition in the aerospace industry and therefore the European Commission intervened.[75]

- Another merger prevented by the Commission was the merger between the Dutch package delivery company TNT and the American counterpart UPS. The European Commission was worried that the takeover would leave the continent with only two dominant players: UPS and DHL.[76]

- Most recently, the proposed takeover of Aer Lingus by Ryanair would have strengthened Ryanair's position in the Irish market and has therefore been blocked by the European Commission.[77]

Oligopolies

[edit]Cartels and collusion

[edit]Possibly the least contentious function of competition law is to control cartels among private businesses. Any "undertaking" is regulated, and this concept embraces de facto economic units, or enterprises, regardless of whether they are a single corporation, or a group of multiple companies linked through ownership or contract.[78]

Cartels

[edit]To violate TFEU article 101, undertakings must then have formed an agreement, developed a "concerted practice", or, within an association, taken a decision. Like US antitrust, this just means all the same thing;[79] any kind of dealing or contact, or a "meeting of the minds" between parties. Covered therefore is a whole range of behaviour from a strong handshaken, written or verbal agreement to a supplier sending invoices with directions not to export to its retailer who gives "tacit acquiescence" to the conduct.[80] Article 101(1) prohibits,

"All agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between member states and which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the common market."

This includes both horizontal (e.g. between retailers) and vertical (e.g. between retailers and suppliers) agreements, effectively outlawing the operation of cartels within the EU. Article 101 has been construed very widely to include both informal agreements (gentlemen's agreements) and concerted practices where firms tend to raise or lower prices at the same time without having physically agreed to do so. However, a coincidental increase in prices will not in itself prove a concerted practice, there must also be evidence that the parties involved were aware that their behaviour may prejudice the normal operation of the competition within the common market. This latter subjective requirement of knowledge is not, in principle, necessary in respect of agreements. As far as agreements are concerned the mere anticompetitive effect is sufficient to make it illegal even if the parties were unaware of it or did not intend such effect to take place.

Exemptions

[edit]Exemptions to Article 101 behaviour fall into three categories. Firstly, Article 101(3) creates an exemption for practices beneficial to consumers, e.g., by facilitating technological advances, but without restricting all competition in the area. In practice the Commission gave very few official exemptions and a new system for dealing with them is currently under review. Secondly, the Commission agreed to exempt 'Agreements of minor importance' (except those fixing sale prices) from Article 101. This exemption applies to small companies, together holding no more than 10% of the relevant market. In this situation as with Article 102 (see below), market definition is a crucial, but often highly difficult, matter to resolve. Thirdly, the commission has also introduced a collection of block exemptions for different contract types. These include a list of contract permitted terms and a list of banned terms in these exemptions.

- Métropole Télévision (M6) v Commission (2001) Case T-112/99, [2001] ECR II 2459

Vertical restraints

[edit]- Exclusive purchasing

- SA Brasserie De Haecht v Consorts Wilkin-Janssen (1967) Case 23/67, [1967] ECR 407

- Stergios Delimitis v Henninger Bräu AG (1991) Case C-234/89, [1991] ECR I 935

- Courage Ltd v Crehan (2001) Case C-453/99

- Franchising

- Pronuptia de Paris GmbH v Pronuptia de Paris Irmgard Schillgalis (1986) Case 161/84, [1986] ECR 353

- Export bans

- Societe Technique Miniere v Maschinenbau Ulm GmbH (1966) Case 56/65, [1966] ECR 337

- Musique Diffusion Française SA v Commission (1983) Cases 100-103/80, [1983] ECR 1825

- Javico International and Javico AG v Yves Saint Laurent Parfums SA (1988) C-306/96, [1998] ECR I 1983

- Consten and Grundig, also

- Exclusive distribution

- L.C. Nungesser KG and Kurt Eisele v Commission (1978) Case 258/78, [1978] ECR 2015

- Consten and Grundig and Maschinenbau Ulm, also

- Selective distribution

- Metro SB-Großmärkte GmbH & Co KG v Commission (1977) Case 26/76, [1977] ECR 1875

- Metro SB-Großmärkte GmbH & Co KG v Commission (1986) Case 75/84, [1986] ECR 3021

- Case C-250/92, Gøttrup-Klim e.a. Grovvareforeninger v Dansk Landbrugs Grovvareselskab AmbA [1994] ECR I-5641

- Case T-328/03, O2 (Germany) GmbH & Co OHG v Commission [2006] ECR II-1231

- T-374/94, T-375/94, T-384/94, T-388/94 European Night Services v Commission [1998] ECR II 3141

- Case C-439/09, Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmétique SAS v Président de l’Autorité de la concurrence and Ministre de l’Économie, de l’Industrie et de l’Emploi [2011]

- Commission Regulation (EC) No. 330/2010, of 20 April 2010 on the application of Article 101(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to categories of vertical agreements and concerted practices OJ (2010) L 102/1

- Commission Regulation (EC) No. 461/2010 for motor vehicle sector

Joint ventures

[edit]- Article 101

- Merger Regulation

- Block Exemption Regulation 2658/2000 and 2659/2000

Enforcement

[edit]Private actions

[edit]Since the Modernisation Regulation, the European Union has sought to encourage private enforcement of competition law.

- Courage Ltd v Crehan (2001) Case C-453/99

- Vicenzo Manfredi v Lloyd Adriactico Assicurazioni SpA (2006) C 295/04, establishing that compensation is available for indirect purchasers as well as direct purchasers.[81]

- Kone AG v ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG (2014) C-557/12, compensation available for umbrella effects in cartelised markets.

The Council Regulation n. 139/2004[82] established antitrust national authorities of EU member States have the competence to judge on undertakings whose economic and financial impact are limited to their respective internal market.

European enforcement

[edit]The task of tracking down and punishing those in breach of competition law has been entrusted to the European Commission, which receives its powers under Article 105 TFEU. Under this Article, the European Commission is charged with the duty of ensuring the application of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU and of investigating suspected infringements of these Articles.[83] The European Commission and national competition authorities have wide on-site investigation powers. Article 105 TFEU grants extensive investigative powers including the notorious power to carry out dawn raids on the premises of suspected undertakings and private homes and vehicles.

There are many ways in which the European Commission could become aware of a potential violation: the Commission may carry out an investigation or an inspection, for which it is empowered to request information from governments, competent authorities of Member States, and undertakings. The commission also provides a leniency policy, under which companies that whistle blow over the anti-competition policies of cartels are treated leniently and may obtain either total immunity or a reduction in fines.[84] In some cases, parties have sought to resist the taking of certain documents during an inspection based on the argument that those documents are covered by legal professional privilege between lawyer and client. The ECJ held that such a privilege was recognised by EC law to a limited extent at least.[85] The Commission also could become aware of a potential competition violation through the complaint from an aggrieved party. In addition, Member States and any natural or legal person are entitled to make a complaint if they have a legitimate interest.

Article 101 (2) TFEU considers any undertaking found in breach of Article 101 TFEU to be null and void and that agreements cannot be legally enforced. In addition, the European Commission may impose a fine pursuant to Article 23 of Regulation 1/2003. These fines are not fixed and can extend into millions of Euros, up to a maximum of 10% of the total worldwide turnover of each of the undertakings participating in the infringement, although there may be a decrease in case of cooperation and increase in case of recidivism. Fines of up to 5% of the average daily turnover may also be levied for every day an undertaking fails to comply with Commission requirements. The gravity and duration of the infringement are to be taken into account in determining the amount of the fine.[86] This uncertainty acts as a powerful deterrent and ensures that companies are unable to undertake a cost/benefit analysis before breaching competition law.

The Commission guideline on the method of setting fines imposed pursuant to Article 23 (2) (a) of Regulation 1/2003[87] uses a two-step methodology:

- The Commission first defines a basic amount of the fine for each involved undertaking or association of undertakings; and then

- Adjusts the basic amount according to the individual circumstances upwards or downwards.

The basic amount relates, inter alia, to the proportion of the value of the sales depending on the degree of the gravity of the infringement. In this regard, Article 5 of the aforementioned guideline states, that

- "To achieve these objectives, it is appropriate for the Commission to refer to the value of the sales of goods or services to which the infringement relates as a basis for setting the fine. The duration of the infringement should also play a significant role in the setting of the fine. It necessarily affects the potential consequences of the infringements on the market. It is therefore considered important that the fine should also reflect the number of years during which an undertaking participated in the infringement."

In a second step, this basic amount may be adjusted on grounds of recidivism or leniency. In the latter case, immunity from fines may be granted to the company who submits evidence first to the European Commission which enables it to carry out an investigation and/or to find an infringement of Article 101 TFEU.

The highest cartel fine which was ever imposed in a single case was related to a cartel consisting of five truck manufacturers. The companies MAN, Volvo/Renault, Daimler, Iveco, and DAF were fined approximately €2.93 billion (not adjusted for Court judgments).[88][89] Between 1997 and 2011 i.e. over a period of 14 years, those companies colluded on truck pricing and on passing on the costs of compliance with stricter emission rules. In this case, MAN was not fined as it revealed the existence of the cartel to the commission (see note regarding leniency below). All companies acknowledged their involvement and agreed to settle the case.

Another negative consequence for the companies involved in cartel cases may be the adverse publicity which may damage the company's reputation.

Questions of reform have circulated around whether to introduce US style treble damages as an added deterrent against competition law violaters. The 2003 "Modernisation Regulation" (Regulation 1/2003) has meant that the European Commission no longer has a monopoly on enforcement, and that private parties may bring suits in national courts. Hence, there has been debate over the legitimacy of private damages actions in traditions that shy from imposing punitive measures in civil actions.[citation needed]

According to the Court of Justice of the European Union, any citizen or business who suffers harm as a result of a breach of the European Union competition rules (Articles 101 and 102 TFEU) should be able to obtain reparation from the party who caused the harm. However, despite this requirement under European law to establish an effective legal framework enabling victims to exercise their right to compensation, victims of European Union competition law infringements to date very often do not obtain reparation for the harm suffered. The amount of compensation that these victims are foregoing is in the range of several billion Euros a year. Therefore, the European Commission has taken a number steps since 2004 to stimulate the debate on that topic and elicit feedback from stakeholders on a number of possible options which could facilitate antitrust damages actions. Based on a Green Paper issued by the Commission in 2005,[90] and the outcomes of several public consultations, the Commission suggested specific policy choices and measures in a White Paper[91] published on 3 April 2008.[92]

In 2014, the European Parliament and European Council issued a joint directive on 'certain rules governing actions for damages under national law for infringements of the competition law provisions of the Members States and of the European Union'.[93]

Many favour ever more uniformity in the interpretation and application of EU competition norms and the procedures to enforce them under this system. However, when there are such differences in many Member States' policy preferences and given the benefits of experimentation, in 2020 one might ask whether more diversity (within limits) might not produce a more efficient, effective and legitimate competition regime.[10]

- Sector inquiry

A special instrument of the European Commission is the so-called sector inquiry in accordance with Art. 17 of Regulation 1/2003.

Article 17 (1) first paragraph of Council Regulation 1/2003 reads:

- "Where the trend of trade between Member States, the rigidity of prices or other circumstances suggest that competition may be restricted or distorted within the common market, the Commission may conduct its inquiry into a particular sector of the economy or into a particular type of agreements across various sectors. In the course of that inquiry, the Commission may request the undertakings or associations of undertakings concerned to supply information necessary for giving effect to Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty (now Art. 101 and 102 TFEU) and may carry out any inspections necessary for that purpose."

In case of sector inquiries, the European Commission follows its reasonable suspicion that the competition in a particular industry sector or solely related to a certain type of contract which is used in various industry sectors is prevented, restricted or distorted within the common market. Thus, in this case not a specific violation is investigated. Nevertheless, the European Commission has almost all avenues of investigation at its disposal, which it may use to investigate and track down violations of competition law. The European Commission may decide to start a sector inquiry when a market does not seem to be working as well as it should. This might be suggested by evidence such as limited trade between Member States, lack of new entrants on the market, the rigidity of prices, or other circumstances suggest that competition may be restricted or distorted within the common market. In the course of the inquiry, the Commission may request that firms – undertakings or associations of undertakings – concerned supply information (for example, price information). This information is used by the European Commission to assess whether it needs to open specific investigations into intervene to ensure the respect of EU rules on restrictive agreements and abuse of dominant position (Articles 101 and 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union).

There has been an increased use of this tool in the recent years, as it is not possible any more for companies to register a cartel or agreement which might be in breach of competition law with the European Commission, but the companies are responsible themselves for assessing whether their agreements constitute a violation of European Union Competition Law (self assessment).

Traditionally, agreements had, subject to certain exceptions, to be notified to the European Commission, and the commission had a monopoly over the application of Article 101 TFEU (former Article 81 (3) EG).[94] Because the European Commission did not have the resources to deal with all the agreements notified, notification was abolished.

One of the most spectacular sector inquiry was the pharmaceutical sector inquiry which took place in 2008 and 2009 in which the European Commission used dawn raids from the beginning. The European Commission launched a sector inquiry into EU pharmaceuticals markets under the European Competition rules because information relating to innovative and generic medicines suggested that competition may be restricted or distorted. The inquiry related to the period 2000 to 2007 and involved investigation of a sample of 219 medicines.[95] Taking into account that sector inquiries are a tool under European Competition law, the inquiry's main focus was company behaviour. The inquiry therefore concentrated on those practices which companies may use to block or delay generic competition as well as to block or delay the development of competing originator drugs.[96]

The following sectors have also been subject of a sector inquiry:

- Financial Services

- Energy

- Local Loop

- Leased Lines

- Roaming

- Media

- Leniency policy

The leniency policy[97] consists in abstaining from prosecuting firms that, being party to a cartel, inform the Commission of its existence. The leniency policy was first applied in 2002.

The Commission Notice on Immunity from fines and reduction of fines in cartel cases (2006)[98] guarantees immunity and penalty reductions to firms who co-operate with the Commission in detecting cartels.

II.A, §8:

The Commission will grant immunity from any fine which would otherwise have been imposed to an undertaking disclosing its participation in an alleged cartel affecting the Community if that undertaking is the first to submit information and evidence which in the Commission's view will enable it to:

(a) carry out a targeted inspection in connection with the alleged cartel; or

(b) find an infringement of Article 81 EC in connection with the alleged cartel.[98]

The mechanism is straightforward.[according to whom?] The first firm to acknowledge their crime and inform the commission will receive complete immunity, that is, no fine will be applied. Co-operation with the commission will also be gratified with reductions in the fines, in the following way:[99]

- The first firm to denounce existence of a cartel receives immunity from prosecution.

- The first firm to provide information offering "significant added value", if not covered by immunity, will be offered a 30-50% reduction in fines.

- A second firm offering "significant added value" can see a 20-30% reduction in fines

- Subsequent firms, where they can also provide "significant added value", can also access reductions up to 20%.[98]

This policy has been of great success[according to whom?] as it has increased cartel detection to such an extent that nowadays most cartel investigations are started according to the leniency policy. The purpose of a sliding scale in fine reductions is to encourage a "race to confess" among cartel members. In cross border or international investigations, cartel members are often at pains to inform not only the EU Commission, but also National Competition Authorities (e.g. the Office of Fair Trading and the Bundeskartellamt) and authorities across the globe.

National authorities

[edit]- United Kingdom

Following the introduction of the Enterprise Act 2002 the Office of Fair Trading[100] was responsible for enforcing competition law (enshrined in The Competition Act 1998) in the UK. These powers are shared with concurrent sectoral regulators such as Ofgem in energy, Ofcom in telecoms, the ORR in rail and Ofwat in water. The OFT was replaced by the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), established on 1 April 2014, combining many of the functions of the OFT and the Competition Commission (CC). Following the United Kingdom's exit from the European Union, the CMA is no longer a relevant national competition authority (NCA).

- France

The Autorité de la concurrence [101] is France's national competition regulator. Its predecessor was established in the 1950s. Today it administers competition law in France, and is one of the leading national competition authorities in Europe.

- Germany

The Bundeskartellamt, [102] or Federal Cartel Office, is Germany's national competition regulator. It was first established in 1958 and comes under the authority of the Federal Ministry of the Economy and Technology. Its headquarters are in the former West German capital, Bonn and its president is Andreas Mundt, who has a staff of 300 people. Today it administers competition law in Germany, and is one of the leading national competition authorities in Europe.

- Italy

The Autorità Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato in Italy was established in 1990.

- Poland

The Office of Competition and Consumer Protection (UOKiK) was established in 1990 as the Antimonopoly Office. In 1989, on the verge of a political breakthrough, when the economy was based on the free market mechanisms, an Act on counteracting monopolistic practices was passed on 24 February 1990. It constituted an important element of the market reform programme. The structure of the economy, inherited from the central planning system, was characterised with a high level of monopolisation, which could significantly limit the success of the economic transformation. In this situation, promotion of competition and counteracting the anti-market behaviours of the monopolists was especially significant. Therefore, the Antimonopoly Office – AO (Urząd Antymonopolowy – UA) was appointed under this act, and commenced its operation in May once the Council of Ministers passed the charter. Also its first regional offices commenced operations in that very same year.

Right now the Office works under the name Office of Competition and Consumer Protection and bases its activities on the newly enacted Act on the Protection of Competition and Consumers from 2007.

Romania

The Romanian Competition Authority (Consiliul Concurenței)[103] has been functioning since 1996 on the basis of Law no. 21/1996. Its powers and, in general, Romanian competition law are closely modeled after the commission – DG Comp and EU competition law.

In addition to the above, the Romanian Competition Authority also has competences with respect to unloyal commercial practices (Law no. 11/1991).

Within the Romanian Competition Authority, there also are since 2011 the Railway National Council (Consiliul Naţional de Supraveghere din Domeniul Feroviar)[104] and since 2017 the Naval Council (Consiliul de Supraveghere din Domeniul Naval)[105] These two structures have exclusively supervisory and regulatory functions.

Finally, it must be said that the Romanian Competition Authority has no competences in the field of consumer protection.

Recent developments

A 2017 study established that in its 20 years of functioning (1996–2016), the impact of the Romanian Competition Authority was of at least 1 billion euros in savings for consumers. In addition, the Authority applied fines of 574 million euros and had a total budget of 158,8 million euros.[106]

The actions of the Romanian Competition Authority in 2017 lead to savings for consumers ranging between 284 and 509 million lei (approximately between EUR 63 and 113 million), while in 2018 the values were similar, between 217 and 514 million lei, according to estimations using a methodology developed by the European Commission.

Romania has moved up in the rankings of the Global Competition Review since 2017 and won 3 stars, along with seven other EU countries (Austria, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Sweden).

According to Global Trend Monitor 2018 (published on PaRR-global.com), Romania is one of the most competitive jurisdictions between countries in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, ranked 10th in this top (after moving up 4 positions compared to the previous year).

The Romanian Competition Authority is currently in the process of implementing a Big Data platform (expected to be finalised in 2020).[107] The Big Data platform would give the Authority significant resources with regards to (i) bid rigging cases; (ii) cartel screening; (iii) Structural and commercial connections between undertakings; (iv) sectorial inquiries; (v) mergers.

- Other authorities

- European Commission: European Commission > Competition.

- European Court of Justice

- Austria: Bundeswettbewerbsbehörde.

- Belgium: De Belgian Competition Authority / L'Autorité belge de concurrence.

- Croatia: Agencija za zaštitu tržišnog natjecanja.

- Czech Republic: Úřad na ochranu hospodářské soutěže

- Denmark: Danish Competition and Consumer Authority.

- Finland: Kilpailuvirasto.

- Hungary: Hungarian Competition Authority

- Netherlands: Autoriteit Consument & Markt (ACM).

- Ireland: Competition Authority (Ireland)

- Italy: Autorità Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato.

- Latvia: Konkurences padome.

- Lithuania: Konkurencijos taryba

- Poland: Office for Competition and Consumer Protection.

- Portugal: Autoridade da Concorrência.

- Slovakia: Protimonopolný úrad Slovenskej republiky

- Slovenia: Urad Republike Slovenije za varstvo konkurence.

- Spain: National Commission on Markets and Competition

- Sweden: Swedish Competition Authority.

- Turkey: Competition Authority (Turkey).

- Greece: Hellenic Competition Commission

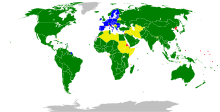

International cooperation

[edit]

Chapter 5 of the post war Havana Charter contained an Antitrust code[108] but this was never incorporated into the WTO's forerunner, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1947. Office of Fair Trading Director and Professor Richard Whish wrote sceptically that it "seems unlikely at the current stage of its development that the WTO will metamorphose into a global competition authority."[109] Despite that, at the ongoing Doha round of trade talks for the World Trade Organization, discussion includes the prospect of competition law enforcement moving up to a global level. While it is incapable of enforcement itself, the newly established International Competition Network[110] (ICN) is a way for national authorities to coordinate their own enforcement activities.

State policy

[edit]Public services

[edit]Article 106(2) of the TFEU states that nothing in the rules can be used to obstruct a member state's right to deliver public services, but that otherwise public enterprises must play by the same rules on collusion and abuse of dominance as everyone else.

Services of general economic interest is more technical term for what are commonly called public services.[111] The settlement under the European Treaties was meant to preserve Europe's social character and institutions. Article 86 refers first of all to "undertakings", which has been defined to restrict the scope of competition law's application. In Cisal[112] a managing director challenged the state's compulsory workplace accident and disease insurance scheme. This was run by a body known as "INAIL". The ECJ held that the competition laws in this instance were not applicable. "Undertaking" was a term that should be reserved for entities that carried on some kind of economic activity. INAIL operated according to the principle of solidarity, because for example, contributions from high paid workers subsidise the low paid workers.[113] Their activities therefore fall outside competition law's scope.

The substance of Article 106(2) also makes clear that competition law will be applied generally, but not where public services being provided might be obstructed. An example is shown in the ‘'Ambulanz Gloeckner'’ case.[114] In Rheinland Pfalz, Germany, ambulances were provided exclusively by a company that also had the right to provide some non-emergency transport. The rationale was that ambulances were not profitable, not the other transport forms were, so the company was allowed to set profits of one sector off to the other, the alternative being higher taxation. The ECJ held that this was legitimate, clarifying that,

"the extension of the medical aid organisations' exclusive rights to the non-emergency transport sector does indeed enable them to discharge their general-interest task of providing emergency transport in conditions of economic equilibrium. The possibility that would be open to private operators to concentrate, in the non-emergency sector, on more profitable journeys could affect the degree of economic viability of the service provided and, consequently, jeopardise the quality and reliability of that service."[115]

The ECJ did however insist that demand on the "subsidising" market must be met by the state's regime. In other words, the state is always under a duty to ensure efficient service. Political concern for the maintenance of a social European economy was expressed during the drafting of the Treaty of Amsterdam, where a new Article 16 was inserted. This affirms, "the place occupied by services of general economic interest in the shared values of the Union as well as their role in promoting social and territorial cohesion." The ongoing debate is at what point the delicate line between the market and public services ought to be drawn.

EU Member states must not allow or assist businesses ("undertakings" in EU jargon) to infringe European Union competition law.[116] As the European Union is made up of independent member states, both competition policy and the creation of the European single market could be rendered ineffective were member states free to support national companies as they saw fit. A 2013 Civitas report lists some of the artifices used by participants to skirt the state aid rules on procurement.[117]

Companies affected by article 106 may be state owned or privately owned companies which are given special rights such as near or total monopoly to provide a certain service. The leading case in 1991, Régie des Télegraphes et des Téléphones v GB-Inno-BM,[118] which involved a small telephone equipment maker, GB and the Belgian state telephone provider, RTT, which had the exclusive power to grant approved phones to connect to the telephone network. GB was selling its phones, which were unapproved by RTT, and at lower prices than RTT sold theirs. RTT sued them, demanding that GB inform customers that their phones were unapproved. GB argued that the special rights enjoyed by RTT under Belgian law infringed Article 86, and the case went to the European Court of Justice (ECJ). The ECJ held that,

"To entrust to an undertaking which markets telephone equipment the task of drawing up specifications for such equipment, of monitoring their application and granting type-approval in respect thereof is tantamount to conferring on it the power to determine at will which equipment can be connected to the public network and thus gives it an obvious advantage over its competitors which is inimical to the equality of chances of traders, without which the existence of an undistorted system of competition cannot be guaranteed. Such a restriction on competition cannot be regarded as justified by a public service of general economic interest..."[119]

The ECJ recommended that the Belgian government have an independent body to approve phone specifications,[120] because it was wrong to have the state company both making phones and setting standards. RTT's market was opened to competition. An interesting aspect of the case was that the ECJ interpreted the effect of RTT's exclusive power as an "abuse" of its dominant position,[121] so no abusive "action" as such by RTT needed to take place. The issue was further considered in Albany International[122] Albany was a textile company, which found a cheap pension provider for its employees. It refused to pay contributions to the "Textile Trade Industry Fund", which the state had given the exclusive right to. Albany argued that the scheme was contrary to EU Competition law. The ECJ ruled that the scheme infringed then Article 86(1), as "undertakings are unable to entrust the management of such a pension scheme to a single insurer and the resulting restriction of competition derives directly from the exclusive right conferred on the sectoral pension fund."[123] But the scheme was justified under then Article 86(2), being a service of general economic interest.

Procurement

[edit]State aid

[edit]Article 107 TFEU, similar to Article 101 TFEU, lays down a general rule that the state may not aid or subsidise private parties in distortion of free competition, but has the power to approve exceptions for specific projects addressing natural disasters or regional development. The general definition of State Aid is set out in Article 107(1) of the TFEU.[124] Measures which fall within the definition of State Aid are unlawful unless provided under an exemption or notified.[125]

For there to be State Aid under Article 107(1) of the TFEU each of the following must be present:

- There is the transfer of Member State resources;

- Which creates a selective advantage for one or more business undertakings;

- That has the potential to distort trade between in the relevant business market; and

- Affects trade between the Member States.

Where all of these criteria are met, State Aid is present and the support shall be unlawful unless provided under a European Commission exemption.[126] The European Commission applies a number of exemptions which enable aid to be lawful.[127] The European Commission will also approve State Aid cases under the notification procedure.[128] A report by the European Defense Agency deals with challenges to a "Level Playing Field for European Defence Industries: the Role of Ownership and Public Aid Practices"[129]

State Aid law is an important issue for all public sector organisations and recipients of public sector support in the European Union[130] because unlawful aid can be clawed back with compound interest.

There is some scepticism about the effectiveness of competition law in achieving economic progress and its interference with the provision of public services. France's former president Nicolas Sarkozy has called for the reference in the preamble to the Treaty of the European Union to the goal of "free and undistorted competition" to be removed.[131] Though competition law itself would have remained unchanged, other goals of the preamble—which include "full employment" and "social progress"—carry the perception of greater specificity, and as being ends in themselves, while "free competition" is merely a means.

Liberalisation

[edit]The EU liberalisation programme entails a broadening of sector regulation, and extending competition law to previously state monopolised industries. The EU has also introduced positive integration measures to liberalise the internal market. There has at times been a tension between introduction of competition and the maintenance of universal and high quality service.[132]

In the Corbeau case,[133] Mr Corbeau had wanted to operate a rapid delivery service for post, which infringed the Belgian Regie des Postes' exclusive right to operate all services. The ECJ held the legislation would be contrary to Article 86 where it was excessive and unnecessary to guarantee the provision of services of general economic interest. It pointed out however that the postal regime (as was the case in most countries) allowed the post office to "offset less profitable sectors against the profitable sectors" of post operations. To provide universal service, a restriction of competition could be justified. The court went on to say,

"to authorise individual undertakings to compete with the holder of the exclusive rights in the sectors of their choice corresponding to those rights would make it possible for them to concentrate on the economically profitable operations and to offer more advantageous tariffs than those adopted by the holders of the exclusive rights since, unlike the latter, they are not bound for economic reasons to offset losses in the unprofitable sectors against profits in the more profitable sectors."

This meant a core of economic sectors in postal services could be reserved for financing the state industry. This was followed by the Postal Services Directive 97/67/EC,[134] which required Member States to "ensure that users enjoy the right to a universal service involving the permanent provision of a postal service... at all points in their territory."[135] This means once a working day deliveries and pick-ups, and that services that could be reserved for state monopolies include "clearance, sorting, transport and delivery of items of domestic correspondence and incoming cross-border correspondence".[136] For countries that had not liberalised postal services in any measure, the directive contained provisions to gradually open up to competition. It was intended to strike a balance between competition and continued quality service.[137] In the Deutsche Post decision[138] the Commission took strong enforcement action. Deutsche Post was accused of predatory pricing in the business parcel delivery sector (i.e. not one of the services "reserved" under the directive) by the private firm UPS. The Commission ordered the structural separation of the normal postal services from business deliveries by Deutsche Post.[139]

- First Railway Directive 91/440/EC, and the Second Railway Package, Third Railway Package and Fourth Railway Package

- Telecoms Package and European Union roaming regulations

Theory

[edit]

Article 101 TFEU's goals are unclear. There are two main schools of thought. The predominant view is that only consumer welfare considerations are relevant there.[140] However, a recent book argues that this position is erroneous and that other Member State and European Union public policy goals (such as public health and the environment) should also be considered there.[141] If this argument is correct then it could have a profound effect on the outcome of cases[142] as well as the Modernisation process as a whole.

The theory behind mergers is that transaction costs can be reduced compared to operating on an open market through bilateral contracts.[143] Concentrations can increase economies of scale and scope. However, often firms take advantage of their increase in market power, their increased market share and decreased number of competitors, which can have a knock on effect on the deal that consumers get. Merger control is about predicting what the market might be like, not knowing and making a judgment.

See also

[edit]- Competition policy

- European Commissioner for Competition

- Irish Competition law

- Relevant market

- SSNIP

- State aid

- US antitrust law

Notes

[edit]- ^ "EUR-Lex – 32004R0139 – EN – EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Terms of Service Violation". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "EEC Council: Regulation No 17: First Regulation implementing Articles 85 and 86 of the Treaty". Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ 64/566/CEE: Décision de la Commission, du 23 septembre 1964, relative à une procédure au titre de l'article 85 du traité (IV-A/00004-03344 «Grundig-Consten») (in French)

- ^ See, Cini & McGowan

- ^ See Gerber & Cassinis

- ^ See Wallace & Pollack

- ^ "Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 of 16 December 2002 on the implementation of the rules on competition laid down in Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty". Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ See Directive (EU) 2019/1 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 to empower the competition authorities of the Member States to be more effective enforcers and to ensure the proper functioning of the internal market (Text with EEA relevance.) OJ L 11, 14.1.2019, p. 3–33.

- ^ a b See Townley, A Framework for European Competition Law: co-ordinated diversity, (2018) Hart Publishing, Oxford Archived 31 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ [1991] ECR I-1979 (C-41/90)

- ^ [2004]

- ^ Albany International BV (1999) [1], per AG Jacobs

- ^ Whish, Richard (2018). Competition Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 829. ISBN 978-0198779063.

- ^ Case M 737, decision of 17thJuly 1996

- ^ Case M 7932, decision of 27thMarch 2017

- ^ Wich, Richard (2018). Competition Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 829. ISBN 978-0198779063.

- ^ Article 2(3), European Merger Regulation 1990

- ^ Art. 2(3) Reg. 129/2005

- ^ Merger Regulation (EC) No 139/2004, art 3(1)

- ^ Europemballage and Continental Can v. Commission (1973) Case 6/72

- ^ France v. Commission (1998) C-68/94

- ^ (1999) T-102/96, [1999] ECR II-753

- ^ Whish, Richard (2018). Competition Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 831. ISBN 978-0198779063.

- ^ Case M 1878, decision of 22 May 2000

- ^ Merger Regulations (EC) No.139/2004

- ^ Art 1 (2) (a) & (b), EUMR 2004

- ^ Italian Flat Glass [1992] ECR ii-1403

- ^ Airtours plc v. Commission (2002) T-342/99, [2002] ECR II-2585, para 62

- ^ Mannesmann, Vallourec and Ilva [1994] CMLR 529, OJ L102 21 April 1994

- ^ Whish, Richard (2018). Competition Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 885. ISBN 978-0198779063.

- ^ De La Mano, Miguel (22 January 2006). "The impact of the new substantive test in European Merger Control" (PDF).

- ^ see the argument put forth in Hovenkamp H (1999) Federal Antitrust Policy: The Law of Competition and Its Practice, 2nd Ed, West Group, St. Paul, Minnesota.

- ^ Kali und Salz AG v. Commission [1975] ECR 499

- ^ Guinness/Grand Metropolitan [1997] 5 CMLR 760, OJ L288; Many in the US are scathing of this approach, see W. J. Kolasky, 'Conglomerate Mergers and Range Effects: It's a long way from Chicago to Brussels' 9 November 2001, Address before George Mason University Symposium Washington, DC.

- ^ a b c Case C-280/08 P Deutsche Telekom v Commission [2010] ECR I-9555

- ^ SPEECH/05/537, 23 September 2005

- ^ a b Guidance on the Commission's enforcement priorities in applying Article 82 TFEU to abusive exclusionary conduct by dominant undertakings OJ [2009] C 45/7

- ^ "Press corner". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ Gerber, David J., The Future of Article 82: Dissecting the Conflict (August 2007). European Competition Law Annual 2007: A Reformed Approach to Article 82 EC (Claus-Dieter Ehlermann and Mel Marquis eds.), 2008; Chicago-Kent College of Law Research Paper. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2159343

- ^ a b Case 322/81 Michelin v Commission [1983] ECR 3461

- ^ United Brands v Commission (1978) C-27/76, [1978] ECR 207

- ^ Hoffmann-La Roche & Co AG v Commission (1979) C-85/76, [1979] ECR 461

- ^ AKZO (1991) [2]

- ^ This was the lowest yet market share of a "dominant" firm, in BA/Virgin 2004

- ^ Michelin [1983]

- ^ Whish, R. and Bailey, D. (2015). Competition law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 212–213

- ^ Gal, Michal S., Abuse of Dominance – Exploitative Abuses (10 March 2015). in HANDBOOK ON EUROPEAN COMPETITION LAW (Lianos and Geradin eds., Edward Elgar, 2013), Chapter 9, pp. 385–422 . Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2576042

- ^ Jones, Alison and Lovdahl Gormsen, Liza, Abuse of Dominance: Exclusionary Pricing Abuses (1 January 2013). I Lianos and D Geradin, Handbook on European Competition Law: Substantive Aspects (Edward Elgar, 2013). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2395165

- ^ Case 226/84 British Leyland v Commission [1986] ECR 3263

- ^ Lang. J – 'How Can the Problems of Exclusionary Abuses under Article 102 TFEU be Resolved?’ [2012] 37 E.L. Rev. 136–155

- ^ Guidance para. [7]

- ^ Case 6/72 Continental Can v Commission [1973] ECR 215

- ^ Case 85/76 Hoffman-La Roche v Commission [1979] ECR 461

- ^ Case C-209/10 Post Danmark EU:C: 2012:172, at para. [22]

- ^ Guidance para. [5]

- ^ Bailey, D. and Whish, R. (2015). Competition law (8th Edition). Oxford University Press, pp. 209

- ^ Case 85/76 Hoffman-La Roche v Commission [1979] ECR 461

- ^ Case T-286/09 Intel v Commission EU:T:2014:547

- ^ Case T-201/04 Microsoft Corpn v Commission [2007] ECR II-3601

- ^ De Poste-La Poste OJ [2002] L 61/32

- ^ Case 24/67 Parke, Davis & Co v Probel [1968] ECR 55

- ^ Case 6/73 Commercial Solvents v Commission [1974] ECR 223

- ^ Case T-340/03 France Telecom SA v Commission (2005)

- ^ Case T-288/97 Irish Sugar plc v Commission [1999]

- ^ Case T 612/17 Google LLC v Commission [2021]

- ^ Case C-209/10 Post Danmark v Commission EU:C:2012:172

- ^ Friederiszick, Hans Wolfgang and Gratz, Linda, Dominant and Efficient – On the Relevance of Efficiencies in Abuse of Dominance Cases (19 December 2012). ESMT White Paper No. WP-12-01. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2191492 pp.23–30

- ^ Loewenthal 'The Defence of "Objective Justification" in the Application of Article 82 EC' (2005) 28 World Competition 455

- ^ Guidance, para [29]

- ^ Case T-30/89 Hilti AG v Commission [1991] ECR II-1439

- ^ Guidance, para [30]

- ^ OJ [2003] L 1/1

- ^ Rasmussen, Scott (2011). "English Legal Terminology: Legal Concepts in Language, 3rd ed. by Helen Gubby. The Hague: Eleven International Publishing, 2011. Pp. 272. ISBN 978-90-8974-547-7. €35.00; US$52.50". International Journal of Legal Information. 39 (3): 394–395. doi:10.1017/s0731126500006314. ISSN 0731-1265. S2CID 159432182.

- ^ Elliott, Michael (8 July 2001). "The Anatomy of the GE-Honeywell Disaster". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Bray, Chad (26 February 2018). "U.P.S. Seeks More Than $2 Billion in Damages Over TNT Bid". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Press corner". European Commission – European Commission. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ See Viho BV v Commission (1995) Case C-73/95, [1995] ECR I-5457

- ^ Van Landewyck (1980) [3], per AG Reischl, there is no need to distinguish an agreement from a concerted practice, because they are merely convenient labels

- ^ Sandoz Prodotti Farmaceutica SpA v Commission (1990) [4]

- ^ Jaremba, Urszula; Lalikova, Laura (1 April 2018). "Effectiveness of Private Enforcement of European Competition Law in Case of Passing-on of Overcharges: Implementation of Antitrust Damages Directive in Germany, France, and Ireland". Journal of European Competition Law & Practice. 9 (4): 226–236. doi:10.1093/jeclap/lpy011. ISSN 2041-7764.

- ^ "Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 of 20 January 2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings (the EC Merger Regulation)". EUR-Lex.

- ^ Paul Craig and Gráinne de Burca (2003). EU LAW, Tect, Cases and Materials. Oxford University Press. p. 1064.

- ^ "About the cartel leniency policy – European Commission". European Commission. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Australian Mining and Smelting Europe Ltd v Commission, ECR 1575". Case 155/79. 1982.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Paul Craig and Gráinne de Burca (2003). EU LAW, Text, Cases and Materials. Oxford University Press. p. 1074.

- ^ "Guidelines on the method of setting fines imposed pursuant to Article 23(2)(a) of Regulation No 1/2003".

- ^ "European Commission – PRESS RELEASES – Press release – Antitrust: Commission fines truck producers €2.93 billion for participating in a cartel".

- ^ "Cartels" (PDF).

- ^ European Commission, Green Paper: Damages actions for breach of the EC antitrust rules, COM(2005)672 final, published 19 December 2005. Retrieved 19 May 2021

- ^ "Actions for damages".

- ^ European Commission, Antitrust: Commission presents policy paper on compensating consumer and business victims of competition breaches, published 3 April 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2021

- ^ "EU Antitrust Damages Directive 2014/104/EU" (PDF).

- ^ Paul Craig and Gráinne de Burca (2003). EU LAW, Text, Cases and Materials. Oxford University Press. p. 1063.

- ^ "Pharmaceutical Sector Inquiry Preliminary Report (DG Competition Staff Working Paper)" (PDF).

- ^ "Communication from the Commission – Executive Summary of the Pharmaceutical Sector Inquiry Report" (PDF).

- ^ see DGCOMP's page on Leniency legislation (immunity from fines and reduction of fines in cartel cases)

- ^ a b c European Commission, Commission Notice on Immunity from fines and reduction of fines in cartel cases (2006/C 298/11)

- ^ see, DGCOMP's European Commission > Competition > Cartels > Leniency

- ^ "Office of Fair Trading". Oft.gov.uk. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ "Autorité de la Concurrence". autoritedelaconcurrence.fr. Archived from the original on 22 February 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ "Bundeskartellamt". Bundeskartellamt.de. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ "Competition Council – ABOUT US". consiliulconcurentei.ro. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ "Consiliul Naţional de Supraveghere din Domeniul Feroviar – DESPRE NOI". consiliulferoviar.ro. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ "Consiliul de Supraveghere din Domeniul Naval – DESPRE NOI". consiliulnaval.ro. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ "Romanian Competition Council 2017 Report" (PDF).

- ^ "Big Data Project" (PDF).

- ^ see a speech by Wood, The Internationalisation of Antitrust Law: Options for the Future 3 February 1995, at http://www.usdoj.gov/atr/public/speeches/future.txt

- ^ Whish (2003) p. 448

- ^ see, http://www.internationalcompetitionnetwork.org/

- ^ Kuhnert, Jan; Leps, Olof (1 January 2017). Neue Wohnungsgemeinnützigkeit (in German). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. pp. 213–258. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-17570-2_8. ISBN 9783658175696.

- ^ C-218/00 Cisal di Battistello Venanzio and C. Sas v Instituto nazionale per l'assicurazione contro gli infortuni sul lavoro (INAIL) [2002] ECR I-691, para 31–45

- ^ Cisal, para 42

- ^ C-475/99 Ambulanz Gloeckner v Landkreis Suedwestpfalz [2001] ECR I-8089, para 52–65

- ^ Ambulanz Gloeckner, para 61

- ^ see, C-311/85 Vereniging van Vlaamse Reisbureaus v ASBL Sociale Dienst van de Plaatselijke en Gewestelijke Overheidsdiensten [1987] ECR 3801, where a Belgian Royal decree incorporated a travel agent association code of conduct, which prohibited discounts (i.e. fixed prices)

- ^ "civitias.org.uk: "Gamekeeper or poacher? Britain and the application of State aid and procurement policy in the European Union" (Garskarth) March 2013" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ C-18/88, [1991] ECR 5941

- ^ para 25, RTT v GB

- ^ para 26

- ^ paragraphs 23 and 24

- ^ C-67/96 Albany International BV v Stichting Bedrijfspensioenfonds Textielindustrie [1999] ECR I-5751

- ^ Albany [1999] ECR I-5751, para 97

- ^ "Eur-lex.europa.eu". Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ "A not-for-profit resource". State Aid Law. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ "A not-for-profit resource". State Aid Law. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ "European Commission – Competition". European Commission. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ "European Commission – Competition". European Commission. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ "eda.europa.eu: "Level Playing Field for European Defence Industries: the Role of Ownership and Public Aid Practices" (2009)". Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "A not-for-profit resource". State Aid Law. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ Removal of competition clause causes dismay, Tobias Buck and Bertrand Benoit, Financial Times p.6 June 23, 2007

- ^ Chalmers (2006) p.1145

- ^ C-320/91 Corbeau [1993] ECR I-2533

- ^ OJ L15/14, amended by Directive 2002/39/EC of 10 June 2003, OJ 2002 L176/21

- ^ Directive 97/67/EC Art. 3(1)

- ^ Directive 97/67/EC Art. 7(1)

- ^ see Directive 97/67/EC Praemble, "the reconciliation of the furtherance of the gradual, controlled liberalisation of the postal market and that of a durable guarantee of the provision of universal service."

- ^ OJ 2001 L125/27

- ^ see also, T-175/99 UPS Europe v Commission [2002] ECR II-1915, para 66

- ^ See, for example, the Commission's Article 101(3) Guidelines, the Court of First Instance's recent Glaxo Case and certain academic works, such as Okeoghene Odudu, The boundaries of EC competition law: the scope of article 81 (OUP 2006)

- ^ Chris Townley, Article 81 EC and Public Policy (Hart 2009)

- ^ The ECJ's judgement in the Glaxo case is eagerly awaited, for example.