Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company

| Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company | |

|---|---|

Brooklyn Rapid Transit logo on a 1907 Brooklyn Union Elevated car | |

| Service | |

| Type | Rapid transit and Streetcar |

| History | |

| Opened | 1896 |

| Closed | 1923 (acquisition by the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Corporation) |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Minimum radius | ? |

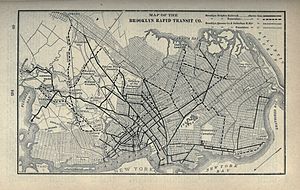

The Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) was a public transit holding company formed in 1896 to acquire and consolidate railway lines in Brooklyn and Queens, New York City, United States. It was a prominent corporation and industry leader using the single-letter symbol B on the New York Stock Exchange.

It operated both passenger and freight services on its rail rapid transit, elevated and subway network, making it unique among the three companies which built and operated subway lines in New York City. It became insolvent in 1919. It was restructured and released from bankruptcy as the Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation in 1923.

Consolidation

[edit]The BRT was incorporated January 18, 1896,[1] and took over the bankrupt Long Island Traction Company in early February[2] acquiring the Brooklyn Heights Railroad and the lessee of the Brooklyn City Rail Road. It then acquired the Brooklyn, Queens County and Suburban Railroad leased on July 1, 1898.[3]

The BRT took over the property of a number of surface railroads, the earliest of which, the Brooklyn, Bath and Coney Island Railroad or West End Line, opened for passenger service on October 9, 1863, between Fifth Avenue at 36th Street at the then border of Brooklyn City and Bath Beach in the Town of Gravesend, New York. A short piece of surface route of this railroad, near Coney Island Creek, is the oldest existing piece of rapid transit right-of-way in New York City, and in the U.S., having opened on June 8, 1864.

Initially the surface and elevated railroad lines ran on steam power. Between 1893 and 1900 the lines were converted to electricity operation. An exception was the service on the Brooklyn Bridge. Trains were operated by cables from 1883 to 1896, when they were converted to electric power[4]

By 1900, it had acquired virtually all of the rapid transit and streetcar operations in its target area:

- Sea Beach Railway, acquired in November 1897[5]

- Sea View Railroad (Coney Island Elevated), acquired in November 1897[5]

- Nassau Electric Railroad (lessee of the Atlantic Avenue Railroad, Brooklyn, Bath and West End Railroad, Coney Island and Gravesend Railway, and South Brooklyn Railway), acquired in November 1898[6] and leased to the BHRR in April 1899[7]

- Brooklyn Elevated Railroad, acquired in March 1899[8] and leased to the BHRR in April 1899[7]

- Brooklyn and Brighton Beach Railroad (Brighton Beach Line), acquired in March 1899[9]

- Kings County Elevated Railroad (Fulton Street Line), acquired in November 1899[10][11] and merged into the Brooklyn Union Elevated on May 24, 1900[12]

- Prospect Park and Coney Island Railroad (Culver Line), leased to the BHRR on June 18, 1899[13]

Only the Coney Island and Brooklyn Railroad and the short Van Brunt Street and Erie Basin Railroad remained independent; the former was acquired in 1913 or 1914.[11]

Expansion

[edit]BRT opened its first short subway segment, consisting only of an underground terminal at the foot of the Williamsburg Bridge at Delancey and Essex Streets in Manhattan on June 16, 1908.[14] This line was extended under Delancey Street and Centre Street to a new five-platform complex at Chambers Street beneath the Manhattan Municipal Building at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge on August 4, 1913.[15] In addition to BRT trains, Long Island Railroad (LIRR) commuter trains also used the new Chambers Street station from its opening until 1917. The elevated railroads were operated by a new corporation, the New York Consolidated Railroad.

In 1913, the BRT, through another subsidiary, the New York Municipal Railway, signed the Dual Contracts with the government of New York City, to construct and operate new subways and other rapid transit lines to be built or improved under these contracts.[16] Almost all subsequent BRT lines were built as part of the contracts. The BRT opened its first Brooklyn subway under Fourth Avenue on June 22, 1915, running over the Manhattan Bridge to a junction with the aforementioned Nassau Street Line at Canal Street.[17] The BRT opened the first segment of its Manhattan main line subway, the Broadway Line, as far as 14th Street–Union Square on September 4, 1917.[18] The Broadway Line was completed in 1920.[19] The BRT's only crosstown Manhattan line, the Canarsie Line, opened in 1924.[20][21]

During the beginning of the BRT's existence, the LIRR was a competitor of the BRT for passengers in Brooklyn and Queens. Despite competing with nearby lines, the BRT and its predecessors also hosted LIRR passenger trains via track sharing agreements and interchanged freight with them. LIRR Passenger service to the BRT's Brooklyn Bridge terminal began after an agreement in 1895, utilizing BRT elevated lines. LIRR passenger service to downtown Manhattan via the BRT subway and Williamsburg Bridge began with the opening of the Chambers Street Station.[22] Both LIRR and BRT motorman were represented by the same union. Today, BRT successor MTA New York City Transit still receives freight deliveries from LIRR freight successor the New York & Atlantic Railroad in Sunset Park and at Linden Yard.

Demise and legacy

[edit]World War I and the attendant massive inflation associated with the war put New York transit operators in a tough position, since their contracts with the City required a five-cent fare be charged, while inflation made the real value of the fare less than three cents in constant currency value. On November 1, 1918, the Malbone Street wreck, the second worst rapid transit train wreck to occur in the United States, occurred on the BRT's Franklin Avenue/Brighton Beach line, killing at least 93 people.[23][24] This further destabilized the financially struggling company, and the BRT filed bankruptcy on December 31, 1918.[25] In 1923 the BRT was restructured and released from bankruptcy as the Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT).

Some of the former elevated system of the BRT, dating to 1885, remains in use today. The largest section is the part of today's BMT Jamaica Line running above Fulton Street from the Alabama Avenue station to a small section turning north after the Crescent Street station. Most of the other surviving structures were either built new or rehabilitated between 1915 and 1922 as part of the Dual Contracts. One piece of structure – the elevated portion of the Franklin Avenue Shuttle, built in 1896 and 1905 – was extensively rebuilt in 1999.

Several BRT-era equipment have been preserved. This includes nine BU cars and five AB Standard cars, all which were also operated by the BMT upon the company's creation in 1923.

See also

[edit]- Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT)

- Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT)

- Independent Subway System (IND)

References

[edit]- ^ "L.I. Traction Reorganization". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY. January 18, 1896. p. 1.

- ^ "Local Stocks and Bonds". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY. February 9, 1896. p. 23.

- ^ "Rapid Transit Statement". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY. August 26, 1898. p. 7.

- ^ "Early Rapid Transit in Brooklyn, 1818 to 1900", nyc subways.com

- ^ a b "Local Stocks and Bonds". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY. November 14, 1897. p. 31.

- ^ "Of the Nassau-Transit Railroad Consolidation Deal". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY. November 6, 1898. p. 30.

- ^ a b "Flynn Enjoins Nassau Lease". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY. April 4, 1899. p. 1.

- ^ "Local Stocks and Bonds". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY. March 19, 1899. p. 35.

- ^ "Rapid Transit Company Gets Brighton Beach R.R.". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY. March 21, 1899. p. 1.

- ^ "Local Stocks and Bonds". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY. April 16, 1899. p. 57.

- ^ a b 1914 Moody's Manual: Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "L Merger Certificate". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY. May 24, 1900. p. 1.

- ^ "Transit Co. Leases P.P. and C.I. Road". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY. June 17, 1899. p. 1.

- ^ "Mayor Runs a Train Over New Bridge". The New York Times. September 17, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ^ "Passenger Killed On Loop's First Day ; Printer, Impatient at Delay in New Bridge Subway, Tries to Walk the Track". The New York Times. August 5, 1913. p. 2. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- ^ "SUBWAY CONTRACTS SOLEMNLY SIGNED; Cheers at the Ceremonial Function When McCall Gets Willcox to Attest" (PDF). The New York Times. March 20, 1913. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ "Steinway Tunnel Tested By Shonts; After Inspection with Engineers He Says Tracks Are the Best He Has Ever Tried. Party Rides Through Tube Interborough's Chief and Other Officials Are Hoisted from a Subway Shaft in a Dirt Bucket" (PDF). The New York Times. June 16, 1915. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- ^ "Broadway Subway Opened To Coney By Special Train. Brooklynites Try New Manhattan Link From Canal St. to Union Square. Go Via Fourth Ave. Tube". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 4, 1917. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ "New B.R.T. Lines Open.; Broadway-Brighton Trains, on Holiday Schedule, Have Light Traffic" (PDF). The New York Times. August 2, 1920. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ "Subway Tunnel Through". The New York Times. August 8, 1919. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ "Celebrate Opening of Subway Link". The New York Times. July 1, 1924. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ Fazio, Alfred (2008). The BMT A Technical and Operational History. BRT Services. ISBN 978-1-60702-864-2.

- ^ "SCORES KILLED OR MAIMED IN BRIGHTON TUNNEL WRECK; First Car Crashes Into Tunnel Pier and Other Cars Grind It to Splinters". The New York Times. November 2, 1918. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ "75 Dead, 100 Hurt in Brighton "L" Wreck". New York Tribune. November 2, 1918. p. 1. ISSN 1941-0646. Retrieved September 26, 2017 – via Library of Congress

.

.

- ^ Hood, Clifton (1993). 722 Miles: The Building of the Subways and How They Transformed New York (1st ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 193. ISBN 0-671-67756-X.

- 1896 establishments in New York City

- 1923 disestablishments in New York (state)

- American companies disestablished in 1923

- American companies established in 1896

- Defunct New York (state) railroads

- Predecessors of the Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation

- Railway companies disestablished in 1923

- Railway companies established in 1896

- Streetcar lines in Brooklyn

- Streetcar lines in Queens, New York