Elizabeth Gómez Alcorta

Elizabeth Gómez Alcorta | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Women, Genders and Diversity | |

| In office 10 December 2019 – 7 October 2022 | |

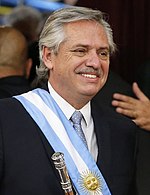

| President | Alberto Fernández |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Ayelén Mazzina |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 November 1972 San Isidro, Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Political party | Patria Grande Front Frente de Todos (since 2019) |

| Alma mater | University of Buenos Aires |

Elizabeth Gómez Alcorta (born 18 November 1972) is an Argentine lawyer, professor and politician. She was the first Minister of Women, Genders and Diversity of Argentina, serving under President Alberto Fernández from 10 December 2019 to 7 October 2022.

She rose to prominence in 2016 as the attorney of activist and social leader Milagro Sala.

Early life and career

[edit]Gómez Alcorta was born in San Isidro, in the suburbs of the Greater Buenos Aires, in 1982. She studied law at the University of Buenos Aires Faculty of Law, graduating in 1997 with honors; she is the first university graduate in her family.[1] She is a member of the Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales (CELS), and worked in the Justice Ministry and the Council of Magistracy, where she became involved in judicial matters pertaining to victims of state-sponsored terrorism during the last military dictatorship (1976–1983).[1][2] Additionally, she has been a faculty of the UBA Faculty of Law, her alma mater.[3]

She rose to prominence in 2016 as the defending attorney of activist and social leader Milagro Sala, who stands accused of embezzlement.[4] According to Gómez Alcorta, Sala was "sentenced for being a woman", and the charges against her constitute a "witch-hunt never seen before in the democratic era";[2][5] she maintains Sala is a political prisoner.[6]

Gómez Alcorta is a member of Mala Junta, a "feminist, popular, mixed and dissident" collective organized within the Patria Grande Front.[1][7] She is a vocal supporter of the legalization of abortion in Argentina.[1][2][3]

Ministry of Women, Genders and Diversity

[edit]Ahead of the 2019 general election, then-presidential candidate Alberto Fernández announced his intention of creating of a new government ministry dedicated to overseeing public policies pertaining to women's issues, especially the issue of gender-based violence against women.[8] Gómez Alcorta was touted by Fernández and vice-presidential candidate Cristina Fernández de Kirchner to head the new ministry ahead of the Frente de Todos ticket's victory in the 2019 election.[9]

Under Gómez Alcorta's vision, the new ministry was subdivided into two secretariats, one dedicated to designing and implementing policies to mitigate gender-based violence against women, and another tasked with implementing policies related to equality and gender and sexual diversity.[9][10] Gómez Alcorta has stated that the ministry's ultimate goal is "to mainstream and federalize gender policies across the Government's administration".[10]

On 31 December 2019, Fernández announced that he would send a bill in 2020 to discuss the legalisation of abortion, ratified his support for its approval, and expressed his wish for "sensible debate".[11] However, in June 2020, he stated that he was "attending to more urgent matters" (referring to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the debt restructuring), and that "he'll send the bill at some point".[12] In November 2020, legal secretary Vilma Ibarra, confirmed that the government would be sending a new bill for the legalisation of abortion to the National Congress that month.[13] The Executive sent the bill, alongside another bill oriented towards women's health care (the "1000 Days Plan"), on 17 November 2020.[14] The bill was passed by the Senate on 30 December 2020,[15] and received presidential assent on 14 January 2021, effectively legalising abortion in Argentina.[16]

Gender-based violence

[edit]In July 2020, Gómez Alcorta presented a $ 18,000 million-national plan against gender-based violence projected for the 2020-2022 period, aimed at reducing extreme violence, ensuring economic autonomy for victims of gender-based violence and seizing cultural and structural aspects.[17] The plan establishes 15 points of action, including the establishment of comprehensive territorial centers, a revamp of the 144 gender violence emergency line, and economic help for women and LGBT+ people at risk.[18]

In 2022 she signed an agreement with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (CIDH) concerning the case of Octavio Romero and Gabriel Gersbach who were a couple in Argentina, unril Romero was murdered. It was agreed that the murder had not been investigated properly and this was because the couple were gay.[19]

LGBT+ rights

[edit]On 4 September 2020, President Fernández signed Decreto 721/2020, which established a 1% employment quota for trans and travesti people in the national public sector. The measure had been previously debated in the Chamber of Deputies as various prospective bills.[20] The decree mandates that at any given point, at least 1% of all public sector workers in the national government must be transgender, as understood in the 2012 Gender Identity Law.[21] The initiative had previously been proposed by Argentine trans and travesti activists such as Diana Sacayán, whose efforts led to the promotion of such laws at the provincial level in Buenos Aires Province in 2015.[22]

On 25 June 2021, the Argentine Senate passed a law mandating the continuity of Decreto 721/2020. The new law, called Promoción del Acceso al Empleo Formal para personas Travestis, Transexuales y Transgénero "Diana Sacayán - Lohana Berkins" ("Promotion of Access to Formal Employment for Travesti, Transsexual and Transgender People Diana Sacayán - Lohana Berkins"), also establishes economic incentives for businesses in the private sector that employ travesti and trans workers, and gives priority in credit lines to trans-owned small businesses.[23][24]

On 20 July 2021, Fernández signed Decreto 476/2021, mandating the National Registry of Persons (RENAPER) to allow a third gender option on all national identity cards and passports, marked as an "X". The measure applies to non-citizen permanent residents who possess Argentine identity cards as well.[25] In compliance with the 2012 Gender Identity Law, this made Argentina one of the few countries in the world to legally recognize non-binary gender on all official documentation.[26][27][28] The 2022 national census, carried out less than a year after the resolution was implemented, counted 56,793 (roughly 0.12%) of the country's population identifying with the "X / other" gender marker.[29]

Resignation

[edit]Gómez Alcorta resigned on 6 October 2022 in protest of the government's eviction of a group of Mapuche people (including several women, some of them pregnant, and children) in the Lafken Winkul Mapu community in Villa Mascardi, Río Negro.[30] Fernández accepted Gómez Alcorta's resignation the following day.[31]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Carbajal, Mariana (7 December 2019). "Quién es Elizabeth Gómez Alcorta". Página/12 (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ a b c "Elizabeth Gómez Alcorta, la futura ministra de las Mujeres, Géneros y Diversidad que calificó a Macri de "cuasi fascista"". La Nación (in Spanish). 6 December 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Elizabeth Gómez Alcorta, la ministra feminista que milita y va a las marchas". Clarín (in Spanish). 6 December 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "La abogada de Milagro Sala, una chica de San Isidro fanática de Fidel Castro". Clarín (in Spanish). 15 December 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ ""Milagro Sala está presa por ser mujer", aseguró una futura ministra de Alberto Fernández". tn.com.ar (in Spanish). 4 December 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Dandan, Alejandra (30 May 2017). "El caso tiene que ver con el disciplinamiento". Página/12 (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Un frente antineoliberal". Página/12 (in Spanish). 27 October 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Alberto: "Crearemos un ministerio de la mujer, la igualdad de género y la diversidad"". Perfil (in Spanish). 11 October 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ a b Iglesias, Mariana (14 December 2019). "Elizabeth Gómez Alcorta: "La sensación que tienen las compañeras en la calle es que el ministerio es de todes"". Clarín (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ a b Carbajal, Mariana (14 December 2019). "Las pautas que guiarán la gestión de Elizabeth Gómez Alcorta". Página/12 (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández confirmó que enviará en 2020 el proyecto para legalizar el aborto". Infobae.com. 31 December 2019.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández, sobre la legalización del aborto: "Ahora tengo otras urgencias"". Clarin.com. 2 June 2020.

- ^ Carbajal, Mariana (10 November 2020). "Aborto legal: el Gobierno enviará el proyecto al Congreso durante noviembre". Página/12 (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ Carbajal, Mariana (17 November 2020). "Aborto legal: Alberto Fernández enviará hoy el proyecto al Congreso". Página/12 (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ Goñi, Uki; Phillips, Tom (30 December 2020). "Argentina legalises abortion in landmark moment for women's rights: Country becomes only the third in South America to permit elective abortions". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ "El presidente argentino firma el decreto para promulgar la ley del aborto". Swissinfo (in Spanish). 14 January 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Slipczuk, Martín (19 July 2020). "Nuevo plan contra la violencia de género: cuáles son sus objetivos y qué cambió". Chequeado (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ Carbajal, Mariana (4 July 2020). "Un Plan Nacional para accionar contra la violencia de género". Página/12 (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "El Estado argentino firmó el acuerdo de solución amistosa en el caso del asesinato de Octavio Romero". Argentina.gob.ar (in Spanish). 2022-09-07. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ^ "Por decreto, el Gobierno estableció un cupo laboral para travestis, transexuales y transgénero". Infobae (in Spanish). 4 September 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "El Gobierno decretó el cupo laboral trans en el sector público nacional". La Nación (in Spanish). 4 September 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "Derecho al trabajo: así está el mapa del cupo laboral travesti-trans en Argentina". Agencia Presentes (in Spanish). 4 September 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "En las redes sociales se festejó la ley de cupo laboral travesti trans". Télam (in Spanish). 25 June 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ Valente, Marcela (25 June 2021). "Transgender job quota law seen 'changing lives' in Argentina". Reuters. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "Decreto 476/2021". Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina (in Spanish). 20 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández pondrá en marcha el DNI para personas no binarias". Ámbito (in Spanish). 20 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Identidad de género: el Gobierno emitirá un DNI para personas no binarias". La Nación (in Spanish). 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Westfall, Sammy (22 July 2021). "Argentina rolls out gender-neutral ID". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ "Censo 2022: resultados provisorios". INDEC (in Spanish). 19 May 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Elizabeth Gómez Alcorta renunció tras fuertes cruces por las detenidas mapuches". Ámbito Financiero (in Spanish). 7 October 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "El Presidente aceptó la renuncia presentada por la ministra Elizabeth Gómez Alcorta". Télam (in Spanish). 7 October 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

External links

[edit]- 1972 births

- Living people

- 21st-century Argentine lawyers

- Argentine feminists

- Argentine human rights activists

- Argentine women human rights activists

- 21st-century Argentine women politicians

- 21st-century Argentine politicians

- Government ministers of Argentina

- Women government ministers of Argentina

- Women's ministers of Argentina

- People from San Isidro, Buenos Aires

- University of Buenos Aires alumni

- Academic staff of the University of Buenos Aires