Magic Johnson

Earvin "Magic" Johnson Jr. (born August 14, 1959) is an American businessman and former professional basketball player. Often regarded as the greatest point guard of all time,[3][4][5][6][7] Johnson spent his entire career with the Los Angeles Lakers in the National Basketball Association (NBA). After winning a national championship with the Michigan State Spartans in 1979, Johnson was selected first overall in the 1979 NBA draft by the Lakers, leading the team to five NBA championships during their "Showtime" era. Johnson retired abruptly in 1991 after announcing that he had contracted HIV, but returned to play in the 1992 All-Star Game, winning the All-Star MVP Award. After protests against his return from his fellow players, he retired again for four years, but returned in 1996, at age 36, to play 32 games for the Lakers before retiring for the third and final time.

Known for his extraordinary court vision, passing abilities, and leadership, Johnson was one of the most dominant players of his era. His career achievements include three NBA Most Valuable Player Awards, three NBA Finals MVPs, nine All-NBA First Team designations, and twelve All-Star games selections. He led the league in regular season assists four times, and is the NBA's all-time leader in average assists per game in both the regular season (11.19 assists per game) and the playoffs (12.35 assists per game).[8][9] He also holds the records for most career playoff assists and most career playoff triple-doubles.[10][11] Johnson was the co-captain of the 1992 United States men's Olympic basketball team ("The Dream Team"),[12] which won the Olympic gold medal in Barcelona. After leaving the NBA in 1991, he formed the Magic Johnson All-Stars, a barnstorming team that traveled around the world playing exhibition games.[13]

Johnson was honored as one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History in 1996 and selected to the NBA 75th Anniversary Team in 2021, and became a two-time inductee into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame—being enshrined in 2002 for his individual career and as a member of the Dream Team in 2010.[14] His friendship and rivalry with Boston Celtics star Larry Bird, whom he faced in the 1979 NCAA finals and three NBA championship series, are well documented.

Since his retirement, Johnson has been an advocate for HIV/AIDS prevention and safe sex,[15] as well as an entrepreneur,[16] philanthropist,[17] broadcaster and motivational speaker.[18] Johnson is a former part-owner of the Lakers and was the team's president of basketball operations in the late 2010s. He is a founding member of Guggenheim Baseball Management, managing entity of the MLB's Los Angeles Dodgers, and is additionally part of ownership groups of the WNBA's Los Angeles Sparks, the MLS' Los Angeles FC, the NFL's Washington Commanders, and the NWSL's Washington Spirit. Johnson has won 15 total championships during his career, one in college, five as an NBA player, and nine as an owner.[19]

Early life

Earvin Johnson Jr. was born in Lansing, Michigan, to General Motors assembly worker Earvin Sr. and school janitor Christine.[20] Johnson, who had six siblings and three half-siblings by his father's previous marriage,[21][22][a] was influenced by his parents' strong work ethic. His mother spent many hours after work each night cleaning their home and preparing the next day's meals, while his father did janitorial work at a used car lot and collected garbage, all while never missing a day at General Motors. Johnson would often help his father on the garbage route, and he was teased by neighborhood children who called him "Garbage Man".[24] His mother raised him in the Seventh-day Adventist Church.[25][26]

Johnson came to love basketball as a young man. His favorite basketball player growing up was Bill Russell, whom he admired more for his many championships than his athletic ability.[27] He also idolized players such as Earl Monroe and Marques Haynes,[28] and practiced "all day".[29] Johnson came from an athletic family. His father played high school basketball in his home state of Mississippi,[30] and Johnson learned the finer points about the game from him. Johnson's mother, originally from North Carolina,[30] had also played basketball as a child, and she grew up watching her brothers play the game.[27]

By the time he had reached the eighth grade, Johnson had begun to think about a future in basketball. He had become a dominant junior high player, once scoring 48 points in a game.[22] Johnson looked forward to playing at Sexton High School, a school with a very successful basketball team and history that also happened to be only five blocks from his home. His plans underwent a dramatic change when he learned that he would be bused to the predominantly white Everett High School instead of going to Sexton,[27][31] which was predominantly black.[22][32] Johnson's sister Pearl and brother Larry had bused to Everett the previous year and did not have a pleasant experience. There were incidents of racism, with rocks being thrown at buses carrying black students and white parents refusing to send their children to school. Larry was kicked off the basketball team after a confrontation during practice, prompting him to beg his brother not to play. Johnson did join the basketball team but became angry after several days when his new teammates ignored him during practice, not even passing the ball to him. He nearly got into a fight with another player before head coach George Fox intervened. Eventually, Johnson accepted his situation and the small group of black students looked to him as their leader.[22] When recalling the events in his autobiography, My Life, he talked about how his time at Everett had changed him:

As I look back on it today, I see the whole picture very differently. It's true that I hated missing out on Sexton. And the first few months, I was miserable at Everett. But being bused to Everett turned out to be one of the best things that ever happened to me. It got me out of my own little world and taught me how to understand white people, how to communicate and deal with them.[22]

High school career

Johnson was first dubbed "Magic" at 15, when he recorded a triple-double of 36 points, 18 rebounds, and 16 assists as a sophomore at Everett.[29] After the game, Fred Stabley Jr., a sports writer for the Lansing State Journal, gave him the moniker[33] despite the belief of Johnson's mother, a devout Christian, that the name was sacrilegious.[29] In his final high school season, Johnson led Everett to a 27–1 win–loss record while averaging 28.8 points and 16.8 rebounds per game,[29] and took his team to an overtime victory in the state championship game.[34] Johnson dedicated the championship victory to his best friend Reggie Chastine, who was killed in a car accident the previous summer.[35] He gave Chastine much of the credit for his development as a basketball player and as a person,[36] saying years later, "I doubted myself back then."[37] Johnson and Chastine were almost always together, playing basketball or riding around in Chastine's car.[24] Upon learning of Chastine's death, Magic ran from his home, crying uncontrollably.[37] Johnson, who finished his high school career with two All-State selections, was considered at the time to be the best high school player ever to come out of Michigan.[35] He was also named to the inaugural McDonald's All-American team, which played in the 1977 Capital Classic.[38][39]

College career

Although Johnson was recruited by several top-ranked colleges such as Indiana and UCLA, he decided to play close to home.[40] His college decision came down to Michigan and Michigan State in East Lansing. He ultimately decided to attend Michigan State when coach Jud Heathcote told him he could play the point guard position. The talent already on Michigan State's roster also drew him to the program.[41]

Johnson did not initially aspire to play professionally, focusing instead on his communication studies major and desire to become a television commentator.[42] Playing with future NBA draftees Greg Kelser, Jay Vincent, and Mike Brkovich, Johnson averaged 17.0 points, 7.9 rebounds, and 7.4 assists per game as a freshman, and led the Spartans to a 25–5 record, the Big Ten Conference title, and a berth in the 1978 NCAA tournament.[29] The Spartans reached the Elite Eight, but lost narrowly to eventual national champion Kentucky.[43]

During the 1978–79 season, Michigan State again qualified for the NCAA tournament, where they advanced to the championship game and faced Indiana State, which was led by senior Larry Bird. In what was the most-watched college basketball game ever,[44] Michigan State defeated Indiana State 75–64, and Johnson was voted Most Outstanding Player of the Final Four.[34] He was selected to the 1978–79 All-American team for his performance that season.[45] After two years in college, during which he averaged 17.1 points, 7.6 rebounds, and 7.9 assists per game, Johnson entered the 1979 NBA draft.[46] Jud Heathcote stepped down as coach of the Spartans after the 1994–95 season, and on June 8, 1995, Johnson returned to the Breslin Center to play in the Jud Heathcote All-Star Tribute Game. He led all scorers with 39 points.[47]

Professional career

Rookie season in the NBA (1979–1980)

Johnson was drafted first overall in 1979 by the Los Angeles Lakers. Johnson said that what was "most amazing" about joining the Lakers was the chance to play alongside Kareem Abdul-Jabbar,[48] the team's 7 ft 2 in (2.18 m) center who became the leading scorer in NBA history.[49] Despite Abdul-Jabbar's dominance, he had failed to win a championship with the Lakers, and Johnson was expected to help them achieve that goal.[50] Lakers coach Jack McKinney had the 6-foot-9-inch (2.06 m) rookie Johnson, who some analysts thought should play forward, be a point guard, even though incumbent Norm Nixon was already one of the best in the league.[51][52] Johnson averaged 18.0 points, 7.7 rebounds, and 7.3 assists per game for the season, was selected to the NBA All-Rookie Team, and was named an NBA All-Star Game starter.[53]

The Lakers compiled a 60–22 record in the regular season and reached the 1980 NBA Finals,[54] where they faced the Philadelphia 76ers, who were led by forward Julius Erving. The Lakers took a 3–2 lead in the series, but Abdul-Jabbar, who averaged 33 points a game in the series,[55] sprained his ankle in Game 5 and could not play in Game 6.[50] Coach Paul Westhead, who had replaced McKinney early in the season after he had a near-fatal bicycle accident,[51][56] decided to start Johnson at center in Game 6; Johnson recorded 42 points, 15 rebounds, 7 assists, and 3 steals in a 123–107 win, while playing guard, forward, and center at different times during the game.[50] Johnson became the only rookie to win the NBA Finals MVP award,[50] and his clutch performance is still regarded as one of the finest in NBA history.[3][57][58] He also became one of four players to win NCAA and NBA championships in consecutive years.[59]

Ups and downs (1980–1983)

Early in the 1980–81 season, Johnson was sidelined after he suffered torn cartilage in his left knee. He missed 45 games,[46] and said that his rehabilitation was the "most down" he had ever felt.[60] Johnson returned before the start of the 1981 playoffs, but the Lakers' then-assistant and future head coach Pat Riley later said Johnson's much-anticipated return made the Lakers a "divided team".[61] The 54-win Lakers faced the 40–42 Houston Rockets in the first round of playoffs,[62][63] where Houston upset the Lakers 2–1 after Johnson airballed a last-second shot in Game 3.[64]

In 1981, after the 1980–81 season, Johnson signed a 25-year, $25 million contract with the Lakers (equivalent to $84,000,000 in 2023), which was the highest-paying contract in sports history up to that point.[65][66] Early in the 1981–82 season, Johnson had a heated dispute with Westhead, who Johnson said made the Lakers "slow" and "predictable".[67] After Johnson demanded to be traded, Lakers owner Jerry Buss fired Westhead and replaced him with Riley. Although Johnson denied responsibility for Westhead's firing,[68] he was booed across the league, even by Laker fans.[29] Buss was also unhappy with the Lakers' offense and had intended on firing Westhead days before the Westhead–Johnson altercation, but assistant GM Jerry West and GM Bill Sharman had convinced Buss to delay his decision.[69] Despite his off-court troubles, Johnson averaged 18.6 points, 9.6 rebounds, 9.5 assists, and a league-high 2.7 steals per game, and was voted a member of the All-NBA Second Team.[46] He also joined Wilt Chamberlain and Oscar Robertson as the only NBA players to tally at least 700 points, 700 rebounds, and 700 assists in the same season.[34] The Lakers advanced through the 1982 playoffs and faced Philadelphia for the second time in three years in the 1982 NBA Finals. After a triple-double from Johnson in Game 6, the Lakers defeated the Sixers 4–2, as Johnson won his second NBA Finals MVP award.[70] During the championship series against the Sixers, Johnson averaged 16.2 points on .533 shooting, 10.8 rebounds, 8.0 assists, and 2.5 steals per game.[71] Johnson later said that his third season was when the Lakers first became a great team,[72] and he credited their success to Riley.[73]

During the 1982–83 NBA season, Johnson's first of nine consecutive double-double seasons, he averaged 16.8 points, 10.5 assists, and 8.6 rebounds per game, and earned his first All-NBA First Team nomination.[46] The Lakers again reached the Finals, and for a third time faced the Sixers, who featured center Moses Malone as well as Erving.[74] With Johnson's teammates Nixon, James Worthy, and Bob McAdoo all hobbled by injuries, the Lakers were swept by the Sixers, and Malone was crowned the Finals MVP.[74] In a losing effort against Philadelphia, Johnson averaged 19.0 points on .403 shooting, 12.5 assists, and 7.8 rebounds per game.[75]

Battles against the Celtics (1983–1987)

Prior to Johnson's fifth season, West—who had become the Lakers general manager—traded Nixon to free Johnson from sharing the ball-handling responsibilities.[76] Johnson averaged another double-double season, with 17.6 points, 13.1 assists, and 7.3 rebounds per game.[46] The Lakers reached the Finals for the third year in a row, where Johnson's Lakers and Bird's Celtics met for the first time in the postseason.[77] The Lakers won the first game, and led by two points in Game 2 with 18 seconds to go, but after a layup by Gerald Henderson, Johnson failed to get a shot off before the final buzzer sounded, and the Lakers lost 124–121 in overtime.[77] In Game 3, Johnson responded with 21 assists in a 137–104 win, but he made several crucial errors late in the contest during Game 4. In the final minute of the game, Johnson had the ball stolen by Celtics center Robert Parish, and then missed two free throws that could have won the game. The Celtics won Game 4 in overtime, and the teams split the next two games. In the decisive Game 7 in Boston, as the Lakers trailed by three points in the final minute, opposing point guard Dennis Johnson stole the ball from Johnson, a play that effectively ended the series.[77] Friends Isiah Thomas and Mark Aguirre consoled him that night, talking until the morning in his Boston hotel room amidst fan celebrations on the street.[78][79] During the Finals, Johnson averaged 18.0 points on .560 shooting, 13.6 assists, and 7.7 rebounds per game.[80] Johnson later described the series as "the one championship we should have had but didn't get".[81]

In the 1984–85 regular season, Johnson averaged 18.3 points, 12.6 assists, and 6.2 rebounds per game, and led the Lakers into the 1985 NBA Finals, where they faced the Celtics again. The series started poorly for the Lakers when they allowed an NBA Finals record 148 points to the Celtics in a 34-point loss in Game 1.[82] However, Abdul-Jabbar, who was now 38 years old, scored 30 points and grabbed 17 rebounds in Game 2, and his 36 points in a Game 5 win were instrumental in establishing a 3–2 lead for Los Angeles.[82] After the Lakers defeated the Celtics in six games, Abdul-Jabbar and Johnson, who averaged 18.3 points on .494 shooting, 14.0 assists, and 6.8 rebounds per game in the championship series,[83][84] said the Finals win was the highlight of their careers.[85]

Johnson again averaged a double-double in the 1985–86 NBA season, with 18.8 points, 12.6 assists, and 5.9 rebounds per game.[46] The Lakers advanced to the Western Conference Finals, but were unable to defeat the Houston Rockets, who advanced to the Finals in five games.[86] In the next season, Johnson averaged a career-high of 23.9 points, as well as 12.2 assists and 6.3 rebounds per game,[46] and earned his first regular season MVP award.[87][88] The Lakers met the Celtics for the third time in the NBA Finals, and in Game 4 Johnson hit a last-second hook shot over Celtics big men Parish and Kevin McHale to win the game 107–106.[89] The game-winning shot, which Johnson dubbed his "junior, junior, junior sky-hook",[89] helped Los Angeles defeat Boston in six games. Johnson was awarded his third Finals MVP title after averaging 26.2 points on .541 shooting, 13.0 assists, 8.0 rebounds, and 2.33 steals per game.[89][90]

Repeat and falling short (1987–1991)

Before the 1987–88 NBA season, Lakers coach Pat Riley publicly promised that they would defend the NBA title, even though no team had won consecutive titles since the Celtics did so in the 1969 NBA Finals.[91] Johnson had another productive season with averages of 19.6 points, 11.9 assists, and 6.2 rebounds per game despite missing 10 games with a groin injury.[46] In the 1988 playoffs, the Lakers swept the San Antonio Spurs in 3 games, then survived two 4–3 series against the Utah Jazz and Dallas Mavericks to reach the Finals and face Thomas and the Detroit Pistons,[92] who with players such as Bill Laimbeer, John Salley, Vinnie Johnson, and Dennis Rodman were known as the "Bad Boys" for their physical style of play.[93] Johnson and Thomas greeted each other with a kiss on the cheek before the opening tip of Game 1, which they called a display of brotherly love.[79][94][95] After the teams split the first six games, Lakers forward and Finals MVP James Worthy had his first career triple-double of 36 points, 16 rebounds, and 10 assists, and led his team to a 108–105 win.[96] Despite not being named MVP, Johnson had a strong championship series, averaging 21.1 points on .550 shooting, 13 assists, and 5.7 rebounds per game.[97] It was the fifth and final NBA championship of his career.[98]

In the 1988–89 NBA season, Johnson's 22.5 points, 12.8 assists, and 7.9 rebounds per game[46] earned him his second MVP award,[99] and the Lakers reached the 1989 NBA Finals, in which they again faced the Pistons. However, after Johnson went down with a hamstring injury in Game 2, the Lakers were no match for the Pistons, who swept them 4–0.[100]

Playing without Abdul-Jabbar for the first time, Johnson won his third MVP award[101] after a strong 1989–90 NBA season in which he averaged 22.3 points, 11.5 assists, and 6.6 rebounds per game.[46] However, the Lakers bowed out to the Phoenix Suns in the Western Conference semifinals, which was the Lakers' earliest playoffs elimination in nine years.[102] Mike Dunleavy became the Lakers' head coach in 1990–91, when Johnson had grown to be the league's third-oldest point guard. He had become more powerful and stronger than in his earlier years, but was also slower and less nimble.[103] Under Dunleavy, the offense used more half-court sets, and the team had a renewed emphasis on defense.[104] Johnson performed well during the season, with averages of 19.4 points, 12.5 assists, and 7 rebounds per game, and the Lakers reached the 1991 NBA Finals. There they faced the Chicago Bulls, led by shooting guard Michael Jordan, a five-time scoring champion regarded as the finest player of his era.[105][106] Although the series was portrayed as a matchup between Johnson and Jordan,[107] Bulls forward Scottie Pippen defended effectively against Johnson. Despite two triple-doubles from Johnson during the series, Finals MVP Jordan led his team to a 4–1 win.[29] In the last championship series of his career, Johnson averaged 18.6 points on .431 shooting, 12.4 assists, and 8 rebounds per game.[108]

HIV announcement and Olympics (1991–1992)

After a physical examination before the 1991–92 NBA season, Johnson discovered that he had tested positive for HIV. In a press conference held on November 7, 1991, Johnson made a public announcement that he would retire immediately.[109] He stated that his wife, Cookie, and their unborn child did not have HIV, and that he would dedicate his life to "battle this deadly disease".[109]

Johnson initially said that he did not know how he contracted the disease,[109] but later acknowledged that it was through having numerous sexual partners during his playing career.[110] He admitted to having "harems of women" and talked openly about his sexual activities because "he was convinced that heterosexuals needed to know that they, too, were at risk".[110] At the time, only a small percentage of HIV-positive American men had contracted it from heterosexual sex,[94][111] and it was initially rumored that Johnson was gay or bisexual, although he denied both.[94] Johnson later accused Isiah Thomas of spreading the rumors, a claim Thomas denied.[79][112]

Johnson's HIV announcement became a major news story in the United States,[111] and in 2004 was named as ESPN's seventh-most memorable moment of the previous 25 years.[109] Many articles praised Johnson as a hero, and the then-U.S. President George H. W. Bush said, "For me, Magic is a hero, a hero for anyone who loves sports."[111]

Despite his retirement, Johnson was voted by fans as a starter for the 1992 NBA All-Star Game at Orlando Arena, although his former teammates Byron Scott and A.C. Green said that Johnson should not play,[113] and several NBA players, including Utah Jazz forward Karl Malone, argued that they would be at risk of contamination if Johnson sustained an open wound while on court.[114] Johnson led the West to a 153–113 win and was crowned All-Star MVP after recording 25 points, 9 assists, and 5 rebounds.[115] The game ended after he made a last-minute three-pointer, and players from both teams ran onto the court to congratulate Johnson.[116]

Johnson was chosen to compete in the Barcelona 1992 Summer Olympics for the U.S. national team, dubbed the "Dream Team" because of the NBA stars on the roster.[117] The Dream Team, which along with Johnson included fellow Hall of Famers such as Bird, Michael Jordan, and Charles Barkley, was considered unbeatable.[118] After qualifying for the Olympics with a gold medal at the 1992 Tournament of the Americas,[119] the Dream Team dominated in Olympic competition, winning the gold medal with an 8–0 record, beating their opponents by an average of 43.8 points per game. Johnson averaged 8.0 points per game during the Olympics, and his 5.5 assists per game was second on the team.[118][120] Johnson played infrequently because of knee problems,[121] but he received standing ovations from the crowd, and used the opportunity to inspire HIV-positive people.[42]

Post-Olympics and later life

Before the 1992–93 NBA season, Johnson announced his intention to stage an NBA comeback. After practicing and playing in several pre-season games, he retired again before the start of the regular season, citing controversy over his return sparked by opposition from several active players.[34] In an August 2011 interview, Johnson said that in retrospect he wished that he had never retired after being diagnosed with HIV, saying, "If I knew what I know now, I wouldn't have retired."[122] Johnson said that despite the physical, highly competitive practices and scrimmages leading up to the 1992 Olympics, some of those same teammates still expressed concerns about his return to the NBA. He said that he retired because he "didn't want to hurt the game."[122]

During his retirement, Johnson has written a book on safe sex, run several businesses, worked for NBC as a commentator, and toured Asia, Australia, and New Zealand with a basketball team of former college and NBA players.[29] In 1985, Johnson created "A Midsummer Night's Magic", a yearly charity event which included a celebrity basketball game and a black tie dinner. The proceeds went to the United Negro College Fund, and Johnson held this event for twenty years, ending in 2005. "A Midsummer Night's Magic" eventually came under the umbrella of the Magic Johnson Foundation, which he founded in 1991.[123] The 1992 event, which was the first one held after Johnson's appearance in the 1992 Olympics, raised over $1.3 million for UNCF. Johnson joined Shaquille O'Neal and celebrity coach Spike Lee to lead the blue team to a 147–132 victory over the white team, which was coached by Arsenio Hall.[124][125]

Return to the Lakers as coach and player (1994, 1996)

Johnson returned to the NBA as coach for the Lakers near the end of the 1993–94 NBA season, replacing Randy Pfund, and Bill Bertka, who served as an interim coach for two games.[126][127] Johnson, who took the job at the urging of owner Jerry Buss, admitted "I've always had the desire (to coach) in the back of my mind." He insisted that his health was not an issue, while downplaying questions about returning as a player, saying, "I'm retired. Let's leave it at that."[128] Amid speculation from general manager Jerry West that he may only coach until the end of the season,[128] Johnson took over a team that had a 28–38 record, and won his first game as head coach, a 110–101 victory over the Milwaukee Bucks.[129] He was coaching a team that had five of his former teammates on the roster: Vlade Divac, Elden Campbell, Tony Smith, Kurt Rambis, James Worthy, and Michael Cooper, who was brought in as an assistant coach.[128][130] Johnson, who still had a guaranteed player contract that would pay him $14.6 million during the 1994–95 NBA season, signed a separate contract to coach the team that had no compensation.[128] The Lakers played well initially, winning five of their first six games under Johnson, but after losing the next five games, Johnson announced that he was resigning as coach after the season. The Lakers finished the season on a ten-game losing streak, and Johnson's final record as a head coach was 5–11.[127] Stating that it was never his dream to coach, he chose instead to purchase a 5% share of the team in June 1994.[29]

At the age of 36, Johnson attempted another comeback as a player when he rejoined the Lakers during the 1995–96 NBA season. During his retirement, Johnson began intense workouts to help his fight against HIV, raising his bench press from 135 to 300 pounds, and increasing his weight to 255 pounds.[37] He officially returned to the team on January 29, 1996,[131] and played his first game the following day against the Golden State Warriors. Coming off the bench, Johnson had 19 points, 8 rebounds, and 10 assists to help the Lakers to a 128–118 victory.[132] On February 14, Johnson recorded the final triple-double of his career, when he scored 15 points, along with 10 rebounds and 13 assists in a victory against the Atlanta Hawks.[132] Playing power forward, he averaged 14.6 points, 6.9 assists, and 5.7 rebounds per game in 32 games, and finished tied for 12th place with Charles Barkley in voting for the MVP Award.[46][133] The Lakers had a record of 22–10 in the games Johnson played, and he considered his final comeback "a success."[131] While Johnson played well in 1996, there were struggles both on and off the court. Cedric Ceballos, upset over a reduction in his playing time after Johnson's arrival, left the team for several days.[134][135] He missed two games and was stripped of his title as team captain.[136] Nick Van Exel received a seven-game suspension for bumping referee Ron Garretson during a game on April 9. Johnson was publicly critical of Van Exel, saying his actions were "inexcusable."[137] Johnson was himself suspended five days later, when he bumped referee Scott Foster, missing three games. He also missed several games due to a calf injury.[131] Despite these difficulties, the Lakers finished with a record of 53–29 and fourth seed in the NBA Playoffs. Although they were facing the defending NBA champion Houston Rockets, the Lakers had home court advantage in the five-game series. The Lakers played poorly in a Game 1 loss, prompting Johnson to express frustration with his role in coach Del Harris' offense.[138] Johnson led the way to a Game 2 victory with 26 points, but averaged only 7.5 points per game for the remainder of the series, which the Rockets won three games to one.[132]

After the Lakers lost to the Houston Rockets in the first round of the playoffs,[139] Johnson initially expressed a desire to return to the team for the 1996–97 NBA season, but he also talked about joining another team as a free agent, hoping to see more playing time at point guard instead of power forward.[131] A few days later, Johnson changed his mind and retired permanently, saying, "I am going out on my terms, something I couldn't say when I aborted a comeback in 1992."[34][131]

Magic Johnson All-Stars

Determined to play competitive basketball despite being out of the NBA, Johnson formed the Magic Johnson All-Stars, a barnstorming team composed of former NBA and college players. In 1994, Johnson joined with former pros Mark Aguirre, Reggie Theus, John Long, Earl Cureton, Jim Farmer, and Lester Conner, as his team played games in Australia, Israel, South America, Europe, New Zealand, and Japan. They also toured the United States, playing five games against teams from the CBA. In the final game of the CBA series, Johnson had 30 points, 17 rebounds, and 13 assists, leading the All-Stars to a 126–121 victory over the Oklahoma City Cavalry.[140] By the time he returned to the Lakers in 1996, the Magic Johnson All-Stars had amassed a record of 55–0, and Johnson was earning as much as $365,000 per game.[37] Johnson played with the team frequently over the next several years, with possibly the most memorable game occurring in November 2001. At the age of 42, Johnson played with the All-Stars against his alma mater, Michigan State. Although he played in a celebrity game to honor coach Jud Heathcoate in 1995,[47] this was Johnson's first meaningful game played in his hometown of Lansing in 22 years. Playing in front of a sold-out arena, Johnson had a triple-double and played the entire game, but his all-star team lost to the Spartans by two points. Johnson's half-court shot at the buzzer would have won the game, but it fell short.[141][142] On November 1, 2002, Johnson returned to play a second exhibition game against Michigan State. Playing with the Canberra Cannons of Australia's National Basketball League instead of his usual group of players, Johnson's team defeated the Spartans 104–85, as he scored 12 points and had 10 assists and 10 rebounds.[143]

Brief period in Scandinavia

In 1999, Johnson joined the Swedish squad M7 Borås (now known as 'Borås Basket'), and was undefeated in five games with the team.[144][145] Johnson also became a co-owner of the club;[146] however, the project failed after one season and the club was forced into reconstruction.[146] He later joined the Danish team The Great Danes.[146]

Rivalry with Larry Bird

Johnson and Bird were first linked as rivals after Johnson's Michigan State Spartans squad defeated Bird's Indiana State Sycamores team in the 1979 NCAA finals. The rivalry continued in the NBA, and reached its climax when Boston and Los Angeles met in three out of four NBA Finals from 1984 to 1987, with the Lakers winning two out of three Finals. Johnson asserted that for him, the 82-game regular season was composed of 80 normal games, and two Lakers–Celtics games. Similarly, Bird admitted that Johnson's daily box score was the first thing he checked in the morning.[116]

Several journalists hypothesized that the Johnson–Bird rivalry was so appealing because it represented many other contrasts, such as the clash between the Lakers and Celtics, between Hollywood flashiness ("Showtime") and Boston/Indiana blue collar grit ("Celtic Pride"), and between blacks and whites.[147][148] The rivalry was also significant because it drew national attention to the faltering NBA. Prior to Johnson and Bird's arrival, the NBA had gone through a decade of declining interest and low TV ratings.[149] With the two future Hall of Famers, the league won a whole generation of new fans,[150] drawing both traditionalist adherents of Bird's dirt court Indiana game and those appreciative of Johnson's public park flair. According to sports journalist Larry Schwartz of ESPN, Johnson and Bird saved the NBA from bankruptcy.[34]

Despite their on-court rivalry, Johnson and Bird became close friends during the filming of a 1984 Converse shoe advertisement that depicted them as enemies.[151][152] Johnson appeared at Bird's retirement ceremony in 1992, and described Bird as a "friend forever";[116] during Johnson's Hall of Fame ceremony, Bird formally inducted his old rival.[150]

In 2009, Johnson and Bird collaborated with journalist Jackie MacMullan on a non-fiction book titled When the Game Was Ours. The book detailed their on-court rivalry and friendship with one another.[153] The following year, HBO developed a documentary about their rivalry titled Magic & Bird: A Courtship of Rivals, which was directed by Ezra Edelman.[154]

Legacy

In 905 NBA games, Johnson tallied 17,707 points, 6,559 rebounds, and 10,141 assists, translating to career averages of 19.5 points, 7.2 rebounds, and 11.2 assists per game, the highest assists per game average in NBA history.[46] Johnson shares the single-game playoff record for assists (24),[155] holds the Finals record for assists in a game (21),[155] and has the most playoff assists (2,346).[156] He is the only player to average 12 assists in an NBA Finals series, achieving it six times.[157] He holds the All-Star Game single-game record for assists (22), and the All-Star Game record for career assists (127).[155]

"Magic is head-and-shoulders above everybody else [...] I've never seen [anybody] as good as him."

Johnson introduced a fast-paced style of basketball called "Showtime", described as a mix of "no-look passes off the fast break, pin-point alley-oops from halfcourt, spinning feeds and overhand bullets under the basket through triple teams."[29] Fellow Lakers guard Michael Cooper said, "There have been times when [Johnson] has thrown passes and I wasn't sure where he was going. Then one of our guys catches the ball and scores, and I run back up the floor convinced that he must've thrown it through somebody."[29][34] Johnson could dominate a game without scoring, running the offense and distributing the ball with flair.[157] In the 1982 NBA Finals, he was named the Finals MVP averaging just 16.2 points, the lowest average of any Finals MVP award recipient in the three-point shot era.[157]

Johnson was exceptional because he played point guard despite being 6 ft 9 in (2.06 m), a size reserved normally for frontcourt players.[29] His career 138 triple-double games places him third all-time behind Oscar Robertson and Russell Westbrook.[159] Johnson is the only player in NBA Finals history to have triple-doubles in multiple series-clinching games.[157]

For his feats, Johnson was voted as one of the 50 Greatest Players of All Time by the NBA in 1996,[160] and selected to the NBA 75th Anniversary Team in 2021.[161] The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame inducted him in 2002.[162] ESPN's SportsCentury ranked Johnson No. 17 in their "50 Greatest Athletes of the 20th Century"[163] In 2006, ESPN.com rated Johnson the greatest point guard of all time, stating, "It could be argued that he's the one player in NBA history who was better than Michael Jordan."[3] Bleacher Report also listed Johnson first in its all-time NBA point guard rankings.[4] In 2022, to commemorate the NBA's 75th anniversary, The Athletic ranked their top 75 players of all time, and named Johnson as the 5th greatest player in NBA history, and the highest ranked point guard.[6] Several of his achievements in individual games have also been named among the top moments in the NBA.[58][164][165] At the 2019 NBA Awards, Johnson received the NBA Lifetime Achievement Award (shared with Bird).[166] In 2022, the NBA began awarding MVPs for the conference finals; the Western Conference Finals MVP trophy is named after Johnson, while the Eastern Conference trophy is named after Bird.[167]

NBA career statistics

| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

| † | Won an NBA championship | * | Led the league | ‡ | NBA record |

Regular season

| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979–80† | L.A. Lakers | 77 | 72 | 36.3 | .530 | .226 | .810 | 7.7 | 7.3 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 18.0 |

| 1980–81 | L.A. Lakers | 37 | 35 | 37.1 | .532 | .176 | .760 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 3.4* | 0.7 | 21.6 |

| 1981–82† | L.A. Lakers | 78 | 77 | 38.3 | .537 | .207 | .760 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 2.7* | 0.4 | 18.6 |

| 1982–83 | L.A. Lakers | 79 | 79 | 36.8 | .548 | .000 | .800 | 8.6 | 10.5* | 2.2 | 0.6 | 16.8 |

| 1983–84 | L.A. Lakers | 67 | 66 | 38.3 | .565 | .207 | .810 | 7.3 | 13.1* | 2.2 | 0.7 | 17.6 |

| 1984–85† | L.A. Lakers | 77 | 77 | 36.1 | .561 | .189 | .843 | 6.2 | 12.6 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 18.3 |

| 1985–86 | L.A. Lakers | 72 | 70 | 35.8 | .526 | .233 | .871 | 5.9 | 12.6* | 1.6 | 0.2 | 18.8 |

| 1986–87† | L.A. Lakers | 80 | 80 | 36.3 | .522 | .205 | .848 | 6.3 | 12.2* | 1.7 | 0.4 | 23.9 |

| 1987–88† | L.A. Lakers | 72 | 70 | 36.6 | .492 | .196 | .853 | 6.2 | 11.9 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 19.6 |

| 1988–89 | L.A. Lakers | 77 | 77 | 37.5 | .509 | .314 | .911* | 7.9 | 12.8 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 22.5 |

| 1989–90 | L.A. Lakers | 79 | 79 | 37.2 | .480 | .384 | .890 | 6.6 | 11.5 | 1.7 | 0.4 | 22.3 |

| 1990–91 | L.A. Lakers | 79 | 79 | 37.1 | .477 | .320 | .906 | 7.0 | 12.5 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 19.4 |

| 1995–96 | L.A. Lakers | 32 | 9 | 29.9 | .466 | .379 | .856 | 5.7 | 6.9 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 14.6 |

| Career | 906 | 870 | 36.7 | .520 | .303 | .848 | 7.2 | 11.2‡ | 1.9 | 0.4 | 19.5 | |

| All-Star | 11 | 10 | 30.1 | .489 | .476 | .905 | 5.2 | 11.5 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 16.0 | |

Playoffs

| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980† | L.A. Lakers | 16 | 16 | 41.1 | .518 | .250 | .802 | 10.5 | 9.4 | 3.1 | 0.4 | 18.3 |

| 1981 | L.A. Lakers | 3 | 3 | 42.3 | .388 | .000 | .650 | 13.7 | 7.0 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 17.0 |

| 1982† | L.A. Lakers | 14 | 14 | 40.1 | .529 | .000 | .828 | 11.3 | 9.3 | 2.9 | 0.2 | 17.4 |

| 1983 | L.A. Lakers | 15 | 15 | 42.9 | .485 | .000 | .840 | 8.5 | 12.8 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 17.9 |

| 1984 | L.A. Lakers | 21 | 21 | 39.9 | .551 | .000 | .800 | 6.6 | 13.5 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 18.2 |

| 1985† | L.A. Lakers | 19 | 19 | 36.2 | .513 | .143 | .847 | 7.1 | 15.2 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 17.5 |

| 1986 | L.A. Lakers | 14 | 14 | 38.6 | .537 | .000 | .766 | 7.1 | 15.1 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 21.6 |

| 1987† | L.A. Lakers | 18 | 18 | 37.0 | .539 | .200 | .831 | 7.7 | 12.2 | 1.7 | 0.4 | 21.8 |

| 1988† | L.A. Lakers | 24 | 24 | 40.2 | .514 | .500 | .852 | 5.4 | 12.6 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 19.9 |

| 1989 | L.A. Lakers | 14 | 14 | 37.0 | .489 | .286 | .907 | 5.9 | 11.8 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 18.4 |

| 1990 | L.A. Lakers | 9 | 9 | 41.8 | .490 | .200 | .886 | 6.3 | 12.8 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 25.2 |

| 1991 | L.A. Lakers | 19 | 19 | 43.3 | .440 | .296 | .882 | 8.1 | 12.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 21.8 |

| 1996 | L.A. Lakers | 4 | 0 | 33.8 | .385 | .333 | .848 | 8.5 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 15.3 |

| Career | 190 | 186 | 39.7 | .506 | .241 | .838 | 7.7 | 12.3‡ | 1.9 | 0.3 | 19.5 | |

Head coaching record

| Regular season | G | Games coached | W | Games won | L | Games lost | W–L % | Win–loss % |

| Playoffs | PG | Playoff games | PW | Playoff wins | PL | Playoff losses | PW–L % | Playoff win–loss % |

| Team | Year | G | W | L | W–L% | Finish | PG | PW | PL | PW–L% | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L.A. Lakers | 1993–94 | 16 | 5 | 11 | .313 | (resigned) | — | — | — | — | — |

| Career[168] | 16 | 5 | 11 | .313 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

Awards and honors

- NBA

- Five-time NBA champion – 1980, 1982, 1985, 1987, 1988[19]

- Three-time NBA Most Valuable Player – 1987, 1989, 1990[46]

- Three-time NBA Finals MVP – 1980, 1982, 1987[46]

- Nine-time All-NBA First Team – 1983–1991[46]

- One-time All-NBA Second Team – 1982[46]

- 12-time NBA All-Star – 1980, 1982–1992[46]

- Two-time NBA All-Star Game MVP – 1990, 1992[46]

- J. Walter Kennedy Citizenship Award – 1992[46]

- Named one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History in 1996[158]

- Selected on the NBA 75th Anniversary Team in 2021[161]

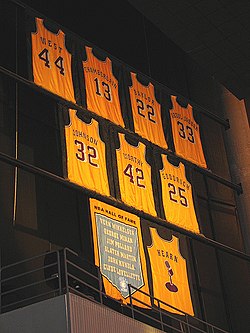

- No. 32 retired by the Los Angeles Lakers[169]

- Statue in front of Crypto.com Arena[170]

- NBA Lifetime Achievement Award – 2019

- Trophy named in Johnson's honor (Earvin "Magic" Johnson Trophy) awarded to Western Conference Finals MVP (established in 2022)[171]

- USA Basketball

- NCAA

- NCAA national championship – 1979[34]

- NCAA basketball tournament Most Outstanding Player – 1979[34]

- No. 33 retired by Michigan State[169]

- Statue at Michigan State[174]

- High school

- 1977 Michigan high school state champion (Lansing Everett High School)[169]

- Halls of Fame

- Two-time Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame inductee:

- 2002 – individual

- 2010 – member of "The Dream Team"[172]

- National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame (class of 2006)[175]

- FIBA Hall of Fame (class of 2017 as a member of "The Dream Team")[176]

- U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame (class of 2009 as a member of "The Dream Team")[177]

- Sports ownership

- Five-time NBA champion – 2000, 2001, 2002, 2009, 2010—as part owner/executive of the Los Angeles Lakers[19]

- WNBA champion – 2016—as part owner of the Los Angeles Sparks[19]

- Two-time World Series champion – 2020, 2024 — as part owner of the Los Angeles Dodgers[19]

- MLS Cup champion – 2022—as part owner of Los Angeles FC[178]

- Media and entertainment

- NAACP Image Awards – 1992 Jackie Robinson Sports Award[179]

- 1993 Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word or Non-Musical Album[180]

- Marca Leyenda – 2001[181]

- Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame – 2001[182][183]

Executive career

On February 21, 2017, Johnson replaced Jim Buss as the president of basketball operations for the Los Angeles Lakers.[184] Under Johnson, the Lakers sought to acquire multiple star players and cleared existing players, including future All-Star D'Angelo Russell, off of their roster in an attempt to free up room under the league's salary cap. The franchise reached an agreement with free agent LeBron James on a four-year contract in 2018, but efforts to trade for Anthony Davis during the 2018–19 season proved unsuccessful. The Lakers did not reach the playoffs during Johnson's executive tenure.[185] In an impromptu news conference on April 9, 2019, Johnson resigned from the Lakers, citing his desire to return to his role as an NBA ambassador.[185][186][187]

Team ownership

In January 2012, Johnson joined with Guggenheim Partners and Stan Kasten in a bid for ownership of the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team.[188] In March 2012, Johnson's ownership group was announced as the winner of the proceedings to buy the Dodgers.[189] The Johnson-led group, which also includes movie executive Peter Guber, paid $2 billion for the Dodgers. Johnson is considered the face of the ownership group while the controlling owner is Mark Walter.[190] The Dodgers won the 2020 and 2024 World Series.[191][192]

Johnson and Guber were also partners in the Dayton Dragons,[190] a Class-A minor league baseball team based in Dayton, Ohio, that sold out more than 1,000 consecutive games, a record for professional sports.[193] Johnson and Guber sold their stake in the Dragons in 2014.[194] Together with Guggenheim, Johnson was also involved in buying the Los Angeles Sparks of the WNBA in 2014.[195] As such, in 2014, Johnson was named one of ESPNW's Impact 25.[196] He won the WNBA championship as the owner in 2016.[197] Johnson announced co-ownership of a Major League Soccer (MLS) expansion franchise, Los Angeles FC, which began play in 2018 and won the MLS Cup in 2022.[198][199][200][178]

In 2023, Johnson invested $240 million in a group headed by Josh Harris that purchased the Washington Commanders of the National Football League (NFL) for $6.05 billion, the highest price ever paid for a sports team.[201][202] A lifelong fan of the NFL, he considered it a "dream" and the greatest achievement of his business career.[201][203] Johnson had previously held talks with other groups interested in buying the Miami Dolphins and Las Vegas Raiders before meeting and joining Harris on an unsuccessful bid on the Denver Broncos in 2022.[201][204] In September 2024, Johnson joined the investment group for the Washington Spirit of the National Women's Soccer League (NWSL).[205]

Personal life

Johnson first fathered a son in 1981 when Andre Johnson was born to Melissa Mitchell. Although Andre was raised by his mother, he visited Johnson each summer, and later worked for Magic Johnson Enterprises as a marketing director.[16]

In 1991, Johnson married Earlitha "Cookie" Kelly in a small wedding in Lansing which included guests Thomas, Aguirre, and Herb Williams.[206] Johnson and Cookie have one son, Earvin III ("EJ"), who is openly gay and a star on the reality show Rich Kids of Beverly Hills.[16][207] The couple adopted a daughter, Elisa, in 1995.[208] Johnson resides in Beverly Hills and has a vacation home in Dana Point, California.[209][210]

Johnson is a Christian[211] and has said his faith is "the most important thing" in his life.[212]

In 2010, Johnson and then-current and former NBA players such as LeBron James, Dwyane Wade, and Bill Russell, as well as Maya Moore from the WNBA, played a basketball game with President Barack Obama as an exhibition for a group of military troops who had been injured in action. The game was played at a gym inside Fort McNair, and reporters covering the president were not allowed to enter. The basketball game was a part of other festivities organized to celebrate Obama's 49th birthday.[213]

Relationship with Jerry Buss

Johnson had a close relationship with Lakers owner Jerry Buss, whom he saw as a mentor and father figure.[214] Calling Buss his "second father" and "one of [his] best friends", Johnson spent five hours visiting Buss at the hospital just a few months before his 2013 death from cancer. Speaking to media just hours after Buss had died, Johnson was emotional, saying, "Without Dr. Jerry Buss, there is no Magic."[215] Buss acquired the team from Jack Kent Cooke in 1979, shortly before he drafted Johnson with the #1 pick in the 1979 NBA draft. Buss took a special interest in Johnson, introducing him to important Los Angeles business contacts and showing him how the Lakers organization was run, before eventually selling Johnson a stake in the team in 1994.[215] Johnson credits Buss with giving him the business knowledge that enabled him to become part owner of the Los Angeles Dodgers.[215][216]

Buss supported Johnson as he revealed his diagnosis of HIV in 1991, and he never hesitated to keep Johnson close to the organization, bringing him in as part-owner, and even as a coach. Johnson had never seriously considered coaching, but he agreed to take the head coaching position with the Lakers in 1994 at Buss' request. In 1992, Buss had given Johnson a contract that paid him $14 million a year, as payback for all the years he was not the league's highest-paid player. Although Johnson's retirement prior to the 1992–93 NBA season voided this contract, Buss insisted that he still be paid.[215] It was this arrangement that allowed Johnson to coach the team without receiving any additional salary.[128][214] After Johnson ended his coaching stint, Buss sold him a 4% stake in the Lakers for $10 million, and Johnson served as a team executive.[215]

Media figure and business interests

In 1997, his production company Magic Johnson Entertainment signed a deal with Fox.[217] In 1998, Johnson hosted a late night talk show on the Fox network called The Magic Hour, but the show was canceled after two months because of low ratings.[218] Shortly after the cancellation of his talk show, Johnson started a record label. The label, initially called Magic 32 Records, was renamed Magic Johnson Music when Johnson signed a joint venture with MCA in 2000. Magic Johnson Music signed R&B artist Avant as its first act.[219][220] Johnson also co-promoted Janet Jackson's Velvet Rope Tour through his company Magicworks.[221] He has also worked as a motivational speaker,[18] and was an NBA commentator for Turner Network Television for seven years,[222] before becoming a studio analyst for ESPN's NBA Countdown in 2008.[223]

Johnson runs Magic Johnson Enterprises, a conglomerate that has a net worth of $700 million;[16] its subsidiaries include Magic Johnson Productions, a promotional company; Magic Johnson Theaters, a nationwide chain of movie theaters; and Magic Johnson Entertainment, a film studio.[224] In addition to these business ventures, Johnson has also created the Magic Card, a pre-paid MasterCard aimed at helping low-income people save money and participate in electronic commerce.[225] In 2006, Johnson created a contract food service with Sodexo USA called Sodexo-Magic.[226][227] In 2004, Johnson and his partner Ken Lombard sold Magic Johnson Theaters to Loews Cineplex Entertainment. The first Magic Johnson Theater located in the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza, closed in 2010 and re-opened in 2011 as Rave Cinema 15.[228] In 2012, Johnson launched a cable TV network called Aspire, featuring programming targeted at black audiences, similar to networks such as Black Entertainment Television (BET) and TV One.[229]

Johnson began thinking of life after basketball while still playing for the Lakers. He wondered why so many athletes had failed at business, and sought advice. During his seventh season in the NBA, he had a meeting with Michael Ovitz, CEO of Creative Artists Agency. Ovitz encouraged him to start reading business magazines and to use every connection available to him. Johnson learned everything he could about business, often meeting with corporate executives during road trips.[230] Johnson's first foray into business, a high-end sporting goods store named Magic 32,[230] failed after only one year, costing him $200,000.[231] The experience taught him to listen to his customers and find out what products they wanted. Johnson has become a leading voice on how to invest in urban communities, creating redevelopment opportunities in underserved areas, most notably through his movie theaters and his partnership with Starbucks. He went to Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz with the idea that he could successfully open the coffee shops in urban areas. After showing Schultz the tremendous buying power of minorities, Johnson was able to purchase 125 Starbucks stores, which reported higher than average per capita sales.[231] The partnership, called Urban Coffee Opportunities, placed Starbucks in locations such as Detroit, Washington, D.C., Harlem, and the Crenshaw District of Los Angeles. Johnson sold his remaining interest in the stores back to the company in 2010, ending a successful twelve-year partnership.[232][233] He has also made investments in urban real estate through the Canyon-Johnson and Yucaipa-Johnson funds.[234] Another major project is with insurance services company Aon Corp.[235] In 2005–2007, Johnson was a part of a syndicate that bought the Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower, then the tallest building in Brooklyn, for $71 million and converted the 512-foot high landmark structure from an office building into luxury condominiums.[236][237] According to Forbes, Johnson became a billionaire in 2023.[238]

In 1990, Johnson and Earl Graves Sr. obtained a large interest in the Washington, D.C. PepsiCo bottling operation, making it the company's largest minority-owned facility in the U.S.[239] Johnson became a minority owner of the Lakers in 1994, having reportedly paid more than $10 million for part ownership. He also held the title of team vice president.[240] Johnson sold his ownership stake in the Lakers in October 2010 to Patrick Soon-Shiong, a Los Angeles surgeon and professor at UCLA,[241] but continued as an unpaid vice president of the team.[242] In February 2017, Johnson returned to the Lakers as an advisor to Jeanie Buss.[243]

In the wake of the Donald Sterling controversy, limited media reports indicated that Johnson had expressed an interest in purchasing the Los Angeles Clippers franchise.[244]

In 2015, Johnson completed his planned acquisition for a "majority, controlling interest" in EquiTrust Life Insurance Company, which manages $14.5 billion in annuities, life insurance and other financial products.[245]

He is an investor for aXiomatic eSports, the ownership company of Team Liquid.[246]

Politics

Johnson is a supporter of the Democratic Party. In 2006, he publicly endorsed Phil Angelides for Governor of California.[247] He supported Hillary Clinton during her 2008 presidential campaign,[248] and in 2010, he endorsed Barbara Boxer in her race for re-election to the U.S. Senate.[249] In 2012, he endorsed Barack Obama for president.[250] He endorsed and appeared in campaign ads for unsuccessful Los Angeles mayoral candidate Wendy Greuel in 2013.[251] In 2015, he once again endorsed Hillary Clinton in her second presidential campaign.[252] He hosted a fundraiser for Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign on August 22, 2016.[253]

HIV activism

I think sometimes we think, "Well, only gay people can get it; it's not going to happen to me", and here I am saying that it can happen to anybody.

— Magic Johnson (November 7, 1991)[254]

Johnson was one of the first sports stars to go public about having HIV.[255] AIDS activist Elizabeth Glaser, to whom Johnson had been introduced by a friend,[256] convinced Johnson to go public about his diagnosis.[256][257] "She made me promise before she died that I would become the face of the disease and really go out and help people and educate people about it", Johnson recalled in a 2011 interview with Frontline.[256]

After announcing his infection in November 1991, Johnson created the Magic Johnson Foundation to help combat HIV,[258] although he later diversified the foundation to include other charitable goals.[259] In 1992, he joined the National Commission on AIDS, a committee appointed by members of Congress and the Bush Administration. Johnson left after eight months, saying that the White House had "utterly ignored" the work of the panel, and had opposed the commission's recommendations, which included universal healthcare and the expansion of Medicaid to cover all low-income people with AIDS.[258][260] He was also the main speaker for the United Nations (UN) World AIDS Day Conference in 1999,[259] and has served as a United Nations Messenger of Peace.[261]

HIV had been associated with intravenous drug users and homosexuals,[258] but Johnson's campaigns sought to show that the risk of infection was not limited to those groups. Johnson stated that his aim was to "help educate all people about what [HIV] is about" and teach others not to "discriminate against people who have HIV and AIDS".[259] Johnson was later criticized by the AIDS community for his decreased involvement in publicizing the spread of the disease.[258][259]

A number of research papers have been written on the "Magic Johnson effect", the effect Johnson's HIV announcement had on various populations, particularly those outside the stereotypes of who got infected with HIV – that is, heterosexuals.[262] Johnson's announcement was a "public-health catalyst", according to a West Virginia University paper,[263] "rapidly correcting the public's understanding of who was at risk of infection".[264] The paper argues there was a "large but temporary increase in the number of AIDS diagnoses for heterosexual men following the announcement" and suggests that, for some of those people, Johnson's announcement "prolonged patients' lifespans as a result of earlier access to medical care".[265] A paper published in AIDS Education and Prevention found that "the announcement by Magic Johnson that he had been infected with HIV was associated with increased concern about HIV and with attitude and behavior changes that would lead to reduced risk".[266]

To prevent his HIV infection from progressing to AIDS, Johnson takes a daily combination of antiretroviral drugs, blocking and containing the virus.[267][268] He has advertised GlaxoSmithKline's drugs,[269] and partnered with Abbott Laboratories to publicize the fight against AIDS in African American communities.[270]

See also

- List of athletes who came out of retirement

- List of NBA career assists leaders

- List of NBA career free throw scoring leaders

- List of NBA career playoff assists leaders

- List of NBA career playoff free throw scoring leaders

- List of NBA career playoff rebounding leaders

- List of NBA career playoff scoring leaders

- List of NBA career playoff steals leaders

- List of NBA career playoff triple-double leaders

- List of NBA career playoff turnovers leaders

- List of NBA career steals leaders

- List of NBA career triple-double leaders

- List of NBA career turnovers leaders

- List of NBA single-game assists leaders

- List of NBA single-game steals leaders

- Magic Johnson's Fast Break, a 1988 video game

Notes

References

- ^ Povtak, Tim (February 7, 1992). "Magic weekend is on tap as Johnson set for NBA encore". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ "2021–22 Big Ten Men's Basketball Media Guide" (PDF). Big Ten Conference. 2021. p. 88. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 9, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Daily Dime: Special Edition – The 10 Greatest Point Guards Ever". ESPN. May 11, 2006. Archived from the original on February 16, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- ^ a b Bailey, Andy. "NBA All-Time Player Rankings: Top 10 Point Guards". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on January 18, 2022. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ The Athletic NBA Staff (February 23, 2022). "NBA 75: Top 75 NBA players of all time, from MJ and LeBron to Lenny Wilkens". The Athletic. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Oram, Bill (February 14, 2022). "NBA 75: At No. 5, Magic Johnson combined dazzling playmaking with charisma to lead the Showtime Lakers to five titles". The Athletic. Archived from the original on August 17, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ Greer, Jordan (September 16, 2022). "Magic Johnson vs. Stephen Curry: Does Warriors star have stats case to surpass Lakers legend as GOAT point guard?". Sporting News. Archived from the original on November 28, 2022. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- ^ "NBA & ABA Career Leaders and Records for Assists Per Game". Basketball Reference. Archived from the original on March 28, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ "NBA & ABA Career Playoff Leaders and Records for Assists Per Game". Basketball Reference. Archived from the original on September 13, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ "NBA & ABA Career Playoff Leaders and Records for Assists". Basketball Reference. Archived from the original on April 24, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ "NBA & ABA Career Playoff Leaders and Records for Triple-Doubles". Basketball Reference. Archived from the original on February 10, 2024. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ Kiisel, Ty (February 6, 2013). "Do you remember who was captain of the Dream Team?". Deseret News. Archived from the original on March 29, 2024. Retrieved May 1, 2024.

- ^ "Magic Johnson." Archived July 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. How Stuff Works. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

- ^ Rohlin, Melissa (April 4, 2020). "Magic Johnson Says It Breaks His Heart That Kobe Bryant Won't Be At Hall Of Fame Ceremony". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ Jaslow, Ryan (November 29, 2013). "Magic Johnson's HIV activism hasn't slowed 22 years after historic announcement". CBS News. Archived from the original on April 5, 2022. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Rovell, Darren (October 8, 2005). "Passing on the Magic". ESPN. Archived from the original on November 25, 2005. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ^ Haire, Thomas (May 1, 2003). "Do You Believe in 'Magic'?". Response Magazine. Archived from the original on October 26, 2006. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ^ a b Springer, Steve (November 7, 2001). "Magic's Announcement: 10 years later, a real survivor". Los Angeles Times. p. D1.

- ^ a b c d e "Magic Johnson now has championship rings in the NBA, MLB and WNBA". Bardown. October 28, 2020. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Eldridge, Earle (November 8, 2004). "Rebounding from basketball court to boardroom". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ^ Johnson, Earvin "Magic", and William Novak. My Life. p. 4. ISBN 0-449-22254-3.

- ^ a b c d e Johnson, Earvin "Magic" (2009). My Life. Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-55817-6. Archived from the original on October 31, 2023. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ Roselius, J. Chris (2011). Magic Johnson: Basketball Star & Entrepreneur: Basketball Star & Entrepreneur. ABDO. ISBN 978-1-61714-945-0. Archived from the original on April 11, 2023. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Meaning of Magic". CoachGeorgeRaveling.com. August 20, 2012. Archived from the original on June 28, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Hyman, Ramona; McChesney, Andrew (May 18, 2016). "Magic Johnson Shows Gratitude to Adventists With $550,000 Donation". Adventist Review. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ Katz, Jesse (October 1, 2003). "Master of Illusion". Los Angeles Magazine. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c Roselius, Chris J. (2011). Magic Johnson: Basketball Star & Entrepreneur. ABDO. ISBN 978-1-61714-945-0. Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ Johnson, Earvin "Magic"; William Novak (1999). My Life. Black Book Company. p. 14. ISBN 1-902799-01-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Magic Johnson Bio". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on January 26, 2012. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ^ a b Springer, Steve (June 5, 2002). "Could It Be Magic?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ McClelland, Edward; McClelland, Ted (2013). Nothin' But Blue Skies: The Heyday, Hard Times, and Hopes of America's Industrial Heartland. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-60819-529-9. Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ "Detroit Board's Busing Decision Termed 'Unwise'". The Argus-Press. July 12, 1973. Retrieved June 27, 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Zillgitt, Jeff (September 27, 2002). "Magic Memories of a Real Star". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 1, 2002. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schwartz, Larry. "Magic made Showtime a show". ESPN. Archived from the original on September 21, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Atkins, Harry (March 28, 1977). "State Basketball Championships Are Now History". The Argus-Press. Associated Press. Retrieved June 27, 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Everett High School Yearbook. Lansing, Mich.: Everett High School. 1977. p. 79. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved January 3, 2023 – via e-yearbook.com.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Gary (February 12, 1996). "True Lies". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on January 3, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ "Boy's Alumni" (PDF). McDonald's All-American Game. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 7, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ "The Origin of the McDonalds All American Game". ESPN. February 26, 2003. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- ^ Johnson, Earvin "Magic"; William Novak (1999). My Life. Black Book Company. p. 45. ISBN 1-902799-01-1.

- ^ Johnson, Earvin "Magic"; William Novak (1999). My Life. Black Book Company. p. 48. ISBN 1-902799-01-1.

- ^ a b Bork, Günter (1994). Die großen Basketball Stars. Copress-Verlag. pp. 56–66. ISBN 3-7679-0369-5.

- ^ "1978 Men's NCAA basketball tournament". CBS Sports. Archived from the original on January 30, 2012. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- ^ Katz, Andy. "From coast to coast, a magical pair". ESPN. Archived from the original on May 22, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ "Consensus All-America Teams (1969–70 to 1978–79)". Sports-Reference. Archived from the original on September 18, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Magic Johnson Statistics". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on December 21, 2007. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- ^ a b "Magic Johnson Returns To The Breslin Center". Michigan State University Athletics. November 1, 2001. Archived from the original on April 11, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Johnson, Earvin "Magic"; William Novak (1999). My Life. Black Book Company. p. 113. ISBN 1-902799-01-1.

- ^ "Regular Season Records: Points". National Basketball Association. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Rookie Makes the Lakers Believe in Magic". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Helin, Kurt (March 5, 2014). "The Extra Pass: Talking "Showtime" Lakers with author Jeff Pearlman". NBC Sports. Archived from the original on December 19, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ^ Ramsay, Jack (2004). Dr. Jack's Leadership Lessons Learned From a Lifetime in Basketball. John Wiley & Sons. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-471-46929-2. Archived from the original on May 1, 2024. Retrieved May 1, 2024.

- ^ "Larry Bird Statistics". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- ^ "1979–80 NBA Season Summary". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2008.

- ^ "1980 NBA Finals Composite Box Score". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on May 12, 2009. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- ^ Shmelter, Richard J. (2012). The Los Angeles Lakers Encyclopedia. McFarland & Company. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-7864-6683-2. Archived from the original on February 10, 2024. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- ^ "NBA's Greatest Moments: Magic Fills in at Center". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ a b McCallum, Jack (June 2, 2006). "Star time". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ "Magic Johnson timeline". USA Today. July 11, 2001. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ^ Johnson, Earvin "Magic"; William Novak (1999). My Life. Black Book Company. p. 135. ISBN 1-902799-01-1.

- ^ Riley, Pat (1994). The Winner Within. Berkley Books. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-425-14175-5.

- ^ "Houston Rockets". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on June 26, 2004. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- ^ "Los Angeles Lakers". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2009.

- ^ Berkow, Ira (November 8, 1991). "Sports of The Times; Magic Johnson's Legacy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ "Johnson rubs LA's Magic lantern for 25 million bucks". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. June 27, 1981. p. 10. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ "Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount – 1790 to Present". MeasuringWorth. Archived from the original on April 8, 2007. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Earvin "Magic"; William Novak (1999). My Life. Black Book Company. p. 141. ISBN 1-902799-01-1.

- ^ Johnson; Novak (1999). My Life. Black Book Company. p. 143. ISBN 1-902799-01-1.

- ^ Ostler, Scott; Springer, Steve (1988). Winnin' Times: The Magical Journey of the Los Angeles Lakers. Collier Books. pp. 154–156, 159–160, 169. ISBN 0-02-029591-X.

- ^ "Lakers' Arduous Season Ends in Victory". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ "1982 NBA Finals Composite Box Score". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on October 14, 2008. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ Johnson, Earvin "Magic"; William Novak (1999). My Life. Black Book Company. p. 148. ISBN 1-902799-01-1.

- ^ Johnson, Earvin "Magic"; William Novak (1999). My Life. Black Book Company. p. 149. ISBN 1-902799-01-1.

- ^ a b "Moses Helps Dr. J, Sixers Reach Promised Land". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ "1983 NBA Finals Composite Box Score". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on December 23, 2008. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ Schrader, Steve (March 23, 2014). "Ticker: Jerry West still fielding Magic Johnson-Norm Nixon questions". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on March 24, 2014. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Celtics Win First Bird–Magic Finals Showdown". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ Lazenby, Roland (2006). The Show: The Inside Story of the Spectacular Los Angeles Lakers in the Words of Those Who Lived It. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-07-143034-0.

- ^ a b c Thomsen, Ian (October 22, 2009). "Isiah blasts Magic Johnson over criticisms in forthcoming book". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- ^ "1984 NBA Finals Composite Box Score". basketball-reference.com. Archived from the original on October 21, 2008. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ Johnson, Earvin "Magic"; William Novak (1999). My Life. Black Book Company. p. 196. ISBN 1-902799-01-1.

- ^ a b "Aging Abdul-Jabbar Finds Youth". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ "1985 NBA Finals Composite Box Score". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2011. Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- ^ "Kareem, Lakers Conquer the Celtic Mystique". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ Johnson; Novak (1999). My Life. Black Book Company. p. 199. ISBN 1-902799-01-1.

- ^ "1986 Playoff Results". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ "All-Time #NBArank: Magic No. 4". ESPN. February 10, 2016. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ "1986–87 NBA MVP Voting". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on February 17, 2008. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Magic Maneuvers Lakers Past Celtics". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011.

- ^ "1987 NBA Finals Composite Box Score". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on August 8, 2011. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ "Riley Guarantees A Repeat". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ "1988 Playoff Results". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ "Bill Laimbeer career summary". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Earvin "Magic"; William Novak (1999). My Life. Black Book Company. p. 225. ISBN 1-902799-01-1.

- ^ Lazenby, p. 261.

- ^ "Lakers Capture the Elusive Repeat". NBA. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ "1988 NBA Finals Composite Box Score". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ Blevins, Dave (2012). The Sports Hall of Fame Encyclopedia: Baseball, Basketball, Football, Hockey, Soccer, Volume 1. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 499. ISBN 978-0-8108-6130-5.

- ^ "1988–89 NBA MVP Voting". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on February 17, 2008. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ "Waiting Game Ends for Impatient Pistons". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ "1989–90 NBA MVP Voting". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on March 1, 2008. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- ^ "1990 Playoff Results". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ Perlman, Jeff (2014). Showtime: Magic, Kareem, Riley, and the Los Angeles Lakers Dynasty of the 1980s. Gotham Books. pp. 396–7. ISBN 978-1-59240-755-2.

- ^ Aldridge, Dave (June 2, 1991). "Johnson Not Ready To Pass Mantle; For 9th Time, Lakers Show Magic Touch". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 28, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

But after a slow start under new coach Mike Dunleavy, Los Angeles found out that new weapons and new emphasis on defense could take it to the same place as Showtime did during the 1980s.

(subscription required) - ^ "Michael Jordan Bio". NBA. Archived from the original on September 2, 2006. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- ^ "Praise from his peers". Sports Illustrated. February 1, 1999. Archived from the original on January 21, 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- ^ "Bulls Finally Get That Championship Feeling". NBA. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ "1991 NBA Finals Composite Box Score". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Weinberg, Rick (September 1, 2004). "7: Magic Johnson announces he's HIV-positive". ESPN. Archived from the original on September 14, 2011. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Friend, Tom (November 7, 2001). "Still stunning the world 10 years later". ESPN. Archived from the original on March 13, 2022. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c Dworkin, Sharon Lee; Wachs, Faye Linda (2000). "The Morality/Manhood Paradox: Masculinity, Sport, and the Media". In McKay, Jim; Messner, Michael; Sabo, Donald (eds.). Masculinities, Gender Relations, and Sport. SAGE. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-0-7619-1272-9. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ Lazenby, pp. 297–8.

- ^ McCallum, Jack (February 17, 1992). "Most Valuable Person". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on January 28, 2010. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ Bork, Gunter (1994). Die großen Basketball Stars. pp. 90–94. ISBN 3-7679-0369-5.

- ^ Cooper, Jon. "1992 NBA All-Star Game". NBA. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Classic NBA Quotes: Magic and Larry". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ Ten of the 12 players on the team were named on the NBA's list of 50 Greatest Players: "The Original Dream Team". NBA. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ a b "Games of the XXVth Olympiad – 1992." Archived July 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. www.usabasketball.com. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ^ "From Rip City to Barcelona". Toledo Blade. Associated Press. July 6, 1992. p. 17. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ "The Original Dream Team". NBA. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ Barnard, Bill (July 29, 1992). "Knee injury knocks Magic out of Dream Team lineup against Germany". The Bend Bulletin. Retrieved June 27, 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Magic Johnson wishes he hadn't retired so early (Video)". Los Angeles Times. August 2, 2011. Archived from the original on May 26, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ "20 years of A Midsummer Night's Magic". magicjohnson.org. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ "Magic Johnson's Gala Midsummer Night Magic Gets $1.3 Mil for UNCF". Jet. October 19, 1992. Archived from the original on April 11, 2023. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ "Game worn Shaquille O'Neal jersey from "A Midsummer Night's Magic" charity game". LiveAuctioneers. Archived from the original on January 3, 2023. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ Araton, Harvey (March 23, 1994). "Pro Basketball; Los Angeles Lakers Hire Magic Johnson To Be Head Coach". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ a b "1993–94 Los Angeles Lakers Schedule and Results". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Magic coaching stint short term?". The Argus-Press. March 24, 1994. Retrieved June 27, 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Johnson gets win in first game as coach". The Fort Scott Tribune. March 28, 1994. Retrieved June 27, 2023.[permanent dead link]