Deportation of Azerbaijanis from Armenia

Mass deportation of Azerbaijanis from Armenia took place several times throughout the 20th century, and sometimes some of them have been described by some authors as acts of forced resettlement and ethnic cleansing.[1][2][3][failed verification][4]

Prior to the October Revolution, Azerbaijanis had made up 43 percent of the population of Yerevan.[5] [better source needed] The Tatar (i.e. Azerbaijani) population endured a process of forced migration from the territory of the First Republic of Armenia and later in the Armenian SSR several times during the 20th century.[6] [better source needed] Under Stalin's policies, approximately 100,000 Azerbaijanis were deported from the Armenian SSR in 1948.[5] Their houses were subsequently inhabited by Armenian repatriates who arrived in the Soviet Union from abroad.[7][8]

Azerbaijanis continued to live in the Armenian SSR until the outbreak of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in 1988–89, when practically all Azerbaijanis in Armenia left or were expelled concurrently with the expulsion/flight of Armenians from Azerbaijan.[3] The deportation was done largely without bloodshed[3] and it was partially in response to Armenians being forced out of Azerbaijan; it was also the last phase of the gradual homogenization of the Armenian republic under Soviet rule.[2]

Beginning of the 20th century

[edit]This article may have misleading content. (October 2022) |

As a result of Armenian-Azerbaijani interethnic conflict in the beginning of the 20th century, as well as Armenian and Azerbaijani nationalists' coordinated policy of ethnic cleansing, a substantial portion of the Armenian and Azerbaijani population was driven out from the territory of both Republic of Armenia and Republic of Azerbaijan. Starting in the middle of 1918, Armenian paramilitary forces under the leadership of General Andranik Ozanian destroyed Muslim settlements in Zangezur (the southernmost part of modern-day Armenia). The British command, which had its own political objectives didn't allow Andranik to extend his activity to Karabakh. Andranik brought 30,000 Armenian Genocide survivors from Eastern Anatolia in the Ottoman Empire, mainly from Mush and Bitlis. Part of Armenian refugees from the Ottoman Empire remained in Zangezur, whereas many others were settled in regions of Yerevan and Daralagoz, where they took the place of outcast Muslims in order to making Armenia's key regions ethnically homogeneous.[9]

Soviet Armenian historian and Bolshevik politician Bagrat Boryan charged that the ARF had not established state authority for the administrative needs of Armenia, but for the “extermination of the Muslim population and looting of their property”.[10] According to data from Caucasian Ethnographical Collection of Academy of Sciences of the USSR, "the settlements of Azerbaijani population in Armenia had become empty." Nataliya Volkova writes that the ruling party of the First Republic of Armenia, the ARF-Dashnaktsutyun, followed a "policy of 'cleansing the country from outsiders'" which "targeted the Muslim population, especially those who had been driven out from Novobayazet, Yerevan, Echmiadzin and Sherur-Daralagoz districts.[6] Volkova writes:

In 1897, out of the 137.9 thousand people living in Zangezur uezd, 63.6 thousand was Armenian (46.2 percent), 71.2 thousand was Azerbaijani (51.7 percent), 1,8 thousand was Kurdish (1.3%). According to agricultural census of 1922, the whole population of Zangezur[a] was 63.5 thousand people, including 59.9 thousand Armenians (89.5%), 6.5 thousand Azerbaijanis (10.2%) and 200 Russians (0.3%).[6][better source needed]

Relocation from the Armenian SSR

[edit]

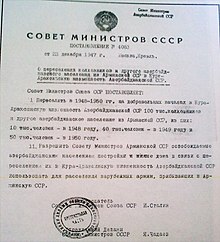

The relocation of the Azerbaijani population during the Stalinist era happened after the establishment of the Armenian SSR. According to the First All-Union Census of the Soviet Union of 1926, Azerbaijanis made up 9.6% of the Republic's population (84,705 people).[11] According to All-Union census of 1939, 130,896 Azerbaijanis lived in Armenian SSR.[12] Results of All-Union census of 1959 show that this figure decreased to 107,748,[13] although Azerbaijanis had one of the highest birth rates in the Soviet Union. The Soviet-era deportation of Azerbaijanis from Armenia and relocation of Armenians living outside the borders of the Soviet Union to Armenia, favoured by the Stalinist policy was the main factor of decrease in the size of Azerbaijani population. In 1937, Muslim Kurds were deported to Kazakhstan from border districts of Armenia with Turkey, immediately after appearance of the problem in USSR-Turkey relations, because of Turkey's denial of the Soviet Union's request for joint control of the Black Sea straits. In 1945 the Soviet Union presented a territorial claim to Turkish territories of Kars and Ardahan. This confrontation in the relations of both countries lasted until Stalin's death. These policies continued until 1953, and Stalin's decisions became the significant step of offering Armenians living in other countries to move to Soviet Armenia. The Armenian SSR was located in an advantageous military-geographical territory at the eastern frontier of Turkey within the context of influencing Turkey. Cleansing Armenia of the Azerbaijani Muslims with the purpose of strengthening Armenia's position within this framework was one of the plans of the Soviet regime. In the Soviet government's judgement, “disloyal”[14] Azerbaijanis were potential “fifth columns” in the case of conflict with Turkey and for this reason Stalin signed off Azerbaijani population's deportation from Armenian SSR in accordance with the Soviet Union's Council of Ministers’ Resolution No. 4083 from December 23, 1947.[15] One clauses of the resolution stated:

To allow the Council of Ministers of Armenian SSR to use the buildings and houses, which were vacated by Azerbaijani population in connection with their resettlement to Kura-Aras Lowland of Azerbaijan SSR for settlement of foreign Armenians coming to Armenian SSR.[16]

Details of resettlement were defined in the Soviet Union's Council of Ministers’ Resolution No. 754. The part of kolkhoz's (collective farm) moveable property was assigned and gratuitous transportation of this property to the new settlement was provided for the deported. The price of moveable property abandoned in Armenia was paid for in kolkhozes at places of the new settlement of Azerbaijanis. Some benefits were given to migrants and at the same time, permanent grants of 1000 rubles were given out per head of the family and 300 rubles per each member of the family. According to historian Vladislav Zubok, due to calls from Grigory Arutinov, the First Secretary of Armenian SSR's Communist Party's Central Committee, Stalin ordered to deport Azerbaijani population from the Armenian SSR to the Azerbaijan SSR. At the same time, he gave consent for the repatriation of 90,000 Armenians to settlements of the newly deported Azerbaijanis.[17][18][19] The resettlement was not voluntary.[20]

According to Krista A. Goff, First Secretary of the Azerbaijan SSR Mir Jafar Baghirov and Arutinov worked together to facilitate Azerbaijani relocation.[21]: 77 At the time, the Kura-Aras lowlands in Azerbaijan were sparsely populated, infrastructurally undeveloped, and economically unproductive. Through resettlement of Azerbaijanis in the Armenian SSR to the Azerbaijan SSR, Azerbaijan would gain a labor force that could make the Kura-Aras region productive. For the most part, Soviet Azerbaijani officials chose to collaborate in the Azerbaijani resettlement. On some occasions, they accused Armenian officials of subverting the resettlement, on the grounds that they were obstructing the relocation of Azerbaijani migrants and not returning the migrants who came back to Armenia. Indeed, some Armenian officials did obstruct resettlement to keep Azerbaijani collective farmers producing in the Armenian SSR.[21]: 78

Numerous reports were received of Azerbaijanis stating their unwillingness to leave the Armenian SSR. The Armenian SSR Interior Ministry reported in 1948 that some Azerbaijanis would even visit cemeteries and pray to the souls of their ancestors "to help them stay in their lands."[citation needed] On the other hand, some groups decided it was better to leave as, in the case of a war with Turkey, they were convinced they would be massacred by Armenians. According to Thomas de Waal, the Azerbaijanis of Armenia once again fell victims to the Armenian–Turkish question.[22] According to Arsene Saparov, more than 100,000 Azerbaijanis were forcibly resettled to Kura-Aras Lowland of the Azerbaijan SSR in three stages: 10,000 people in 1948, 40,000 in 1949, and 50,000 in 1950.[23] Krista Goff, however, has contested that based on the available documentation only a total of 45,000 were resettled through the period 1948-53.[21]: 134, 269

Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

[edit]According to the census of 1979, Azerbaijanis were the largest minority in Armenia making up 5.3% of Armenia's population (approximately 160,800 people).[24]

According to a 2003 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees report, Azerbaijanis were expelled from Armenia or fled out of fear following the anti-Armenian pogroms in Sumgait and Baku of 1988–89.[25] Armenian nationalists, together with the Soviet republic's administration, were thought to have co-operated in driving Azerbaijanis out.[26] According to data collected by Arif Yunusov, about 40,897 Azerbaijani families fled and 216 Azerbaijanis died (127 of them killed by Armenians) during the resettlements in 1988–1991.[27] Soviet official statistics confirmed 25 victims from that list to be killed in the northern regions of Armenia, including the Gugark district, where 11 people were killed during the Gugark pogrom. The remainder of the Azerbaijani population was driven away from the country in 1991.[28] By 2004, not more than 30 Azerbaijanis were living in Armenia.[29]

Razmik Panossian refers to this population transfer as the last phase of Armenia's gradual ethnic homogenization and an episode of ethnic cleansing that increased the country's ethnic Armenian population from 97% to 98%.[30] According to Russian human rights defender Sergey Lyozov, the mass deportation of Azerbaijanis from Armenia in November 1988 was one of the factors that turned the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict into a "battle to the end" involving either physical extermination or total expulsion of an ethnic group.[31]

Changes in the demographic character were accompanied by a policy of renaming settlements and toponyms on the territory of Armenian SSR. In total, more than 600 toponyms have been renamed from 1924 to 1988 in Armenian SSR.[32] Such alterations of toponyms continued in post-Soviet period. According to State Committee's superior Manuk Vardanyan, 57 toponyms were further renamed in 2006, with plans to rename a further 21 settlements in 2007.[33] Azerbaijani cultural institutions in Armenia also suffered as a result of the expulsions. The Agababa-Childir and Daralagoz ashig schools entirely disappeared in the wake of the expulsion of Azerbaijanis from Armenia.[34]

Population statistics of Azerbaijanis in Armenia

[edit]Chronology

[edit]• 1947 - The Soviet Union's Councils of Ministers’ resolution about resettlement of Azerbaijanis from Armenian SSR to Azerbaijan SSR

• 1947–1950 - Eviction of Azerbaijanis from Armenian SSR

• November, 1987- Deportation of Azerbaijanis from Kapan and Meghri districts of the Armenian SSR[35]

• February 21, 1988 - Mass demonstrations began in Yerevan for the unification of Nagorno-Karabakh with the Armenia SSR

• November, 1988 - Mass deportation of Azerbaijanis from Armenia[36]

Number of Azerbaijanis in Armenia

[edit]| 1926 | 1939 | 1959 | 1970 | 1979 | 1989 | 2001 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azerbaijanis (number of people and their percentage as part of Armenia's population) | 84,705 (9.6%) | 130,896 (10.2%) | 107,748 (6.1%) | 148,189 (5.9%) | 160,841 (5.2%) | 84,860 (2.5%) | 29 (0.01%) |

Changes in the demographic structure of Yerevan

[edit]According to the Russian census of 1897, Yerevan, then a town called Erivan, had 29,006 residents: 12,523 of them were Armenian-speakers and 12,359 were Tatar-speakers.[37] According to the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedia, Azerbaijanis (Tatars) made up more than 12 thousand (41 percent) of 29 thousand inhabitants in the city.[38] According to the census of 1959, Armenians made up 96 percent population of the country and in 1989 more than 96.5 percent. Azerbaijanis then made up only 0.1 percent of Yerevan's population, this change was attributed to Soviet nationalities policies.[39] Yerevan's population was changed in Armenians' favour by sidelining the local Muslim population.[40] As a result of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, the Azerbaijanis of Yerevan were driven away.[41][42]

See also

[edit]- Yeraz

- Nagorno-Karabakh war

- Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- Forced settlements in the Soviet Union

- Azerbaijanis in Armenia

- Deportation of Azerbaijanis from Armenia (1947-1950)

- Flight of Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Zangezur uezd was partitioned between the Armenian and Azerbaijan Soviet republics, with the latter receiving the predominantly Muslim-inhabited southeastern slopes, thereby reducing the Muslim population of the remainder of the county.

References

[edit]- ^ ""Черный сад": Глава 5. Ереван. Тайны Востока". BBC Russia. 8 July 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ a b Barrington, Lowell W. (2006). After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial & Postcommunist States. USA: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-06898-9.

In late 1988, the entire Azerbaijani population (including Muslim Kurds) – some 167,000 people – was kicked out of the Armenian SSR. In the process, dozens of people died due to isolated Armenian attacks and adverse conditions. This population transfer was partially in response to Armenians being forced out of Azerbaijan, but it was also the last phase of the gradual homogenization of the republic under Soviet rule. The population transfer was the latest, and not so "gentle," episode of ethnic cleansing that increased Armenia's homogenization from 90 percent to 98 percent. Nationalists, in collaboration with the Armenian state authorities, were responsible for this exodus

- ^ a b c Suny, Ronald Grigor (Winter 1999–2000). Provisional Stabilities: The Politics of Identities in Post-Soviet Eurasia. International Security. Vol 24, No. 3. pp. 139–178.

A second reason for Armenian unity and coherence was the fact that progressively through the seventy years of Soviet power, the republic grew more Armenian in population until it became the most ethnically homogeneous republic in the USSR. On several occasions local Muslims were removed from its territory and Armenians from neighboring republics settled in Armenia. The nearly 200,000 Azerbaijanis who lived in Soviet Armenia in the early 1980s either left or were expelled from the republic in 1988-89, largely without bloodshed. The result was a mass of refugees flooding into Azerbaijan, many of them becoming the most radical opponents of Armenians in Azerbaijan.

- ^ Thomas Ambrosio (2001). Irredentism: ethnic conflict and international politics. USA: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 160. ISBN 0-275-97260-7. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ a b Grenoble, Lenore A. Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Springer: 2003, p.135 ISBN 1402012985

Prior to the Revolution, Azerbaijanis had made up 43 percent of the population of Erevan, but approximately 100,000 were deported from the Armenian SSR in 1948 (Dragadze 1990:166–7).

- ^ a b c Volkova, Nataliya G. (1969). Caucasian Ethnographical Collection of Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Vol. IV. USSR, Institute of Ethnography named after M. Maklay, Academy of Sciences, USSR, Moscow: Nauka. p. 10. 2131 Т11272.

- ^ Burdett 1998, p. 2.

- ^ - Н. А. Добронравин, профессор, доктор филологических наук Archived 2016-06-01 at the Wayback Machine: Около 53 тыс. азербайджанцев оказались переселены из Армении, в основном из горных районов, в Кура-Араксинскую низменность Азербайджана, где быстро развивалось хлопководство. Освободившиеся дома заселяли армяне, переехавшие в Советский Союз из-за рубежа. — Page 334

- ^ Bloxham 2005, p. 103-105.

- ^ Firuz Kazemzadeh (1951). The struggle for Transcaucasia, 1917-1921. New York: Philosophycal Library inc. pp. 214–215. ISBN 9780802208347.

- ^ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1926 года. Национальный состав населения по регионам республик СССР". Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1939 года. Национальный состав населения по регионам республик СССР". Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1959 года. Национальный состав населения по регионам республик СССР". Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Vladislav M. Zubok (2007). A failed empire: the Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev. New York: UNC Press Books. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-8078-3098-7.

he decided to resume the "ethnic cleansing" of South Caucasus from suspicious and potential disloyal elements

- ^ "Постановление N: 754 Совета министров СССР. О мероприятиях по переселению колхозников и другого азербайджанского населения из Армянской ССР в Кура-Араксинскую низменность Азербайджанской ССР". Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Постановление N: 754 Совета министров СССР. О мероприятиях по переселению колхозников и другого азербайджанского населения из Армянской ССР в Кура-Араксинскую низменность Азербайджанской ССР". Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Vladislav M. Zubok (2007). A failed empire: the Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev. New York: UNC Press Books. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-8078-3098-7.

After the dream of returning "ancestral lands" in Turkey did not materialize, the leaders of Georgia and Armenia began to scheme against Azerbaijan. Grigory Arutyunov complained that he had no room for repatriates (although, instead of the projected 400,000 Armenians arrived in Soviet Armenia, only 90,000 arrived in Soviet Armenia). He proposed to resettle Azeri peasants living in Armenian territory in Azerbaijan

- ^ Hafeez Malik (1996). Central Asia: its strategic importance and future prospects. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 149. ISBN 0-312-16452-1.

- ^ N.A.Dobravin. "АЗЕРБАЙДЖАН: "ПОСЛЕДНИЙ РУБЕЖ" ЕВРОПЫ НА ГРАНИЦЕ C ИРАНОМ?*" (PDF). p. 334. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ A.L.P. Burdett (1998). Slavic & Balkan Titles: Armenia: Political And Ethnic Boundaries 1878–1948. Cambridge University. p. 1 volume. ISBN 978-1-85207-955-0. Archived from the original on 2017-09-17. Retrieved 2011-09-01.

- ^ a b c Krista A. Goff. Nested Nationalism: Making and Unmaking Nations in the Soviet Caucasus. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2021.

- ^ de Waal 2015, p. 197.

- ^ Arseny Saparov. "The alteration of place names and construction of national identity in Soviet Armenia". Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "NATIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE POPULATION IN ARMENIA". Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "International Protection Considerations Regarding Armenian Asylum-Seekers and Refugees" (PDF). UNHCR. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Lowell W. Barrington (2006). After independence: making and protecting the nation in postcolonial & postcommunist states. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. p. 231. ISBN 0-472-06898-9.

In late 1988, the entire Azerbaijani population (including Muslim Kurds) — some 167000 people — was deported out of the Armenian SSR. In the process, dozens of people died due to isolated Armenian attacks and adverse conditions. This population transfer was partially in response to Armenians being forced out of Azerbaijan, but it was also the last phase of the gradual homogenization of the republic under Soviet rule. The population transfer was the latest episode of ethnic cleansing that increased Armenia's homogenization from 90 percent to 98 percent. Nationalists, in collaboration with the Armenian state authorities, were responsible for this exodus

- ^ Thomas de Waal. "A free-thinker loses his freedom in Azerbaijan". Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Armenia. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices". US Department of State. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "SECOND REPORT SUBMITTED BY ARMENIA PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25, PARAGRAPH 1 OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES Demographic Landscape of the Republic of Armenia" (PDF). Council of Europe ACFC/SR/II (2004) 010. 24 November 2004. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ After Independence by Lowell W. Barrington. University of Michigan Press, 2006; p. 231. ISBN 0-472-06898-9

- ^ Sergey Lyozov. Попытка понимания. Университетская книга, 1999; p. 339

- ^ Azeri Arseny Saparov. "The alteration of place names and construction of national identity in Soviet Armenia". Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "News Armenia". Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Региональный семинар ЮНЕСКО по продвижению конвенции об охране нематериального культурного наследия стран Европы и Северной Америки Казань, Российская Федерация, 15-17 декабря 2004. 15-17 декабря 2004. НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЙ ДОКЛАД ПО СОСТОЯНИЮ ОХРАНЫ НЕМАТЕРИАЛЬНОГО КУЛЬТУРНОГО НАСЛЕДИЯ В АЗЕРБАЙДЖАНЕ" (PDF). Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Kaufman, Stuart J. (2001). Modern hatreds: the symbolic politics of ethnic war. Ithaca, New York. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-1-5017-0199-3. OCLC 1160511946.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Карабах: хронология конфликта". BBC Russian. 29 August 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г." Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона. "Эривань"". Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Lenore A. Grenoble (2003). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. University of Michigan Press. pp. 134–135. ISBN 1-4020-1298-5.

- ^ Ronald Grigor Suny (1993). Looking toward Ararat: Armenia in modern history. Indiana University Press. p. 138. ISBN 0-253-20773-8.

Ronald Grigor Suny Looking Toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana State University, 1993

- ^ "The New Yorker, A Reporter at Large, "Roots,"". April 15, 1991.

- ^ "Том де Ваал. Черный сад. Между миром и войной. Глава 5. Ереван. Тайны Востока". BBC News. 8 July 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bloxham, Donald (2005). The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199226887.

- Burdett, A.L.P. (1998). Slavic & Balkan Titles: Armenia: Political And Ethnic Boundaries - 1878–1948. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781852079550. Archived from the original on 2017-09-17. Retrieved 2011-09-01.

- de Waal, Thomas (1996). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through peace and war. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7.

- de Waal, Thomas (2015). Great Catastrophe : Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-935069-8.