Ashik

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (April 2020) |

An ashik (Azerbaijani: aşıq, azb:آشؽق; Turkish: âşık; —all from Azerbaijani: aç) or ashugh (Armenian: աշուղ; Georgian: აშუღი)[1]: 1365 [2][3] is traditionally a singer-poet and bard who accompanies his song—be it a dastan (traditional epic story, also known as hikaye) or a shorter original composition—with a long-necked lute (usually a bağlama or saz)[4]: 225 in Azerbaijani culture, including Turkish and South Azerbaijani[4] and non-Turkic cultures of South Caucasus (primarily Armenian and Georgian).[5]: 15–36 [6]: 47 [7][3] In Azerbaijan, the modern ashik is a professional musician who usually serves an apprenticeship, masters playing the bağlama, and builds up a varied but individual repertoire of Turkic folk songs.[8]

The word ashiq (Arabic: عاشق, meaning "in love" or "lovelorn") is the nominative form of a noun derived from the word ishq (Arabic: عشق, "love"), which in turn may be related to the Avestan and Persian iš- ("to wish, desire, seek").[9] The term is synonymous with ozan in Turkish and Azerbaijani, which it superseded during the fifteenth to sixteenth centuries.[10]: 368 [11] Other alternatives include saz şair (meaning "saz poet") and halk şair ("folk poet"). In Armenian, the term gusan, which referred to creative and performing artists in public theaters of Parthia and ancient as well as medieval Armenia, is often used as a synonym. [5]: 20 [1]: 851–852

History

[edit]

The ashik tradition in Turkic cultures of Anatolia, Azerbaijan and Iran has its origin in the Shamanistic beliefs of ancient Turkic peoples.[12] The ancient ashiks were called by various names such as bakshy/bakhshi/Baxşı, dede (dədə), and uzan or ozan. Among their various roles, they played a major part in perpetuation of oral tradition, promotion of communal value system and traditional culture of their people. These wandering bards or troubadours are part of current rural and folk culture of Azerbaijan, and Iranian Azerbaijan, Turkey, the Turkmen Sahra (Iran) and Turkmenistan, where they are called bakshy. Thus, ashik, in traditional sense, may be defined as travelling bards who sang and played saz, an eight or ten string plucking instrument in the form of a long-necked lute.

Judging based on the Turkic epic Dede Korkut,[13] the roots of ashiks can be traced back to at least the 7th century, during the heroic age of the Oghuz Turks. This nomadic tribe journeyed westwards through Central Asia from the 9th century onward and settled in present Turkey, Azerbaijan Republic and North-west areas of Iran. Naturally, their music was evolved in the course of the grand migration and ensuing feuds with the original inhabitants the acquired lands. An important component of this cultural evolution was that the Turks embraced Islam within a short time and of their own free will. Muslim Turk dervishes, desiring to spread the religion among their brothers who had not yet entered the Islamic fold, moved among the nomadic Turks. They choose the folk language and its associate musical form as an appropriate medium for effective transmission of their message. Thus, ashik literature developed alongside mystical literature and was refined starting since the time of Turkic Sufi Khoja Akhmet Yassawi in early twelfth century.[14]

The single most important event in the history of ashik music was the ascent to the throne of Shah Isma'il (1487–1524), the founder of the Safavid dynasty. He was a prominent ruler-poet and has, apart from his diwan compiled a mathnawi called Deh-name, consisting of some eulogies of Ali, the fourth Caliph of early Islam. He used the pen-name Khata'i and, in ashik tradition, is considered as an amateur ashik .[15] Isma'il's praised playing Saz as a virtue in one of his renowned qauatrains;[16]

Bu gün ələ almaz oldum mən sazım --- (Today, I embraced my Saz)

Ərşə dirək-dirək çıxar mənim avazım --- (My song is being echoed by heavens)

Dörd iş vardır hər qarındaşa lazım: --- (Four things are required for the life:)

Bir elm, bir kəlam, bir nəfəs, bir saz. --- (Conscience, speech, respiration, and Saz.)

According to Köprülü's studies, the term ashik was used instead of ozan in Azerbaijan and in areas of Anatolia after the 15th century.[17][10] After the demise of Safavid dynasty in Iran, Turkish culture could not sustain its early development among the elites. Instead, there was a surge in the development of verse-folk stories, mainly intended for performance by ashiks in weddings. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union the governments of new republics in Caucasus region and Central Asia sought their identity in traditional cultures of their societies. This elevated the status of ashugs as the guardians of national culture. The newfound unprecedented popularity and frequent concerts and performances in urban settings have resulted in rapid innovative developments aiming to enhance the urban-appealing aspects of ashik performances.

Ashugh music in Armenia

[edit]

A concise account of the ashik (called ashugh in Armenian) music and its development in Armenia is given in Garland Encyclopedia of World Music.[1]: 851–852 In Armenia, the ashugh are known since the 16th century onward, acting as the successors to the medieval gusan art. By far the most notable of the ashugh of all was Sayat Nova (1712–95), who honed the art of troubadour musicianship to crowning refinement.[18]

Ashik music in Iranian Azerbaijan

[edit]

During the Pahlavi era Ashiks frequently performed in coffee houses in all the major cities of east and west Azerbaijan in Iran. Tabriz was the eastern center for the ashiks and Urmia the western center. In Tabriz ashiks most often performed with two other musicians, a balaban player and a qaval player; in Urmia the ashik was always a solo performer.[19] After the Islamic revolution music was banned.{fact} Ten years later, ashik Rasool Ghorbani, who had been forced to make a living as a travelling salesman, aspired to return to the glorious days of fame and leisure. He started composing songs with religious and revolutionary themes. The government, realizing the propaganda potential of these songs, allowed their broadcast in national radio and sent Rasool to perform in some European cities.[citation needed] This facilitated the emergence of the ashik music as the symbol of Azeri cultural identity.[citation needed]

In September 2009, Azerbaijan's ashik art was included into UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage.[20]

The foundations of ashik art

[edit]

Ashik art combines poetic, musical and performance ability. Ashiks themselves describe the art as the unified duo of saz and söz (word).This duo is conspicuously featured in a popular composition by Səməd Vurğun:[21]

Binələri çadır çadır --- (The peaks rise up all around like tents)

Çox gəzmişəm özüm dağlar --- (I have wandered often in these mountains)

İlhamını səndən alıb --- (My saz and söz take inspiration)

Mənim sazım, sözüm dağlar. --- (From you, mountains.)

The following subsections provide more details about saz and söz.

Musical instruments

[edit]

Mastering in playing saz is the essential requirement for an ashik. This instrument, a variant of which is known as Bağlama, is a stringed musical instrument and belongs to the family of long-necked lutes.[22] Often performances of ashiks are accompanied by an ensemble of balaban[23] and qaval performers. During Eurovision Song Contest 2012 all three instruments were symbolically played as a cultural symbol of the host country, Azerbaijan.

Poetry genres

[edit]The most spread poetry genres are gerayly, qoshma and tajnis.[24][25]

Ethical code of behaviour and attitude for ashiks

[edit]The defining characteristic of ashik profession is the ethical code of behaviour and attitude, which has been summarized by Aşiq Ələsgər in the following verses;[26][27]

Aşıq olub diyar-diyar gəzənin ----(To be a bard and wander far from home)

Əzəl başdan pürkəmalı gərəkdi --- (You knowledge and thinking head must have.)

Oturub durmaqda ədəbin bilə --- (How you are to behave, you too must know,)

Mə'rifət elmində dolu gərəkti --- (Politeness, erudition you must have.)

Xalqa həqiqətdən mətləb qandıra --- (He should be able to teach people the truth,)

Şeytanı öldürə, nəfsin yandıra --- (To kill evil within himself, refrain from ill emotions,)

El içinde pak otura pak dura --- (He should socialize virtuously)

Dalısınca xoş sedalı gərəkdi --- (Then people will think highly of him)

Danışdığı sözün qiymətin bilə --- (He should know the weight of his words,)

Kəlməsindən ləl'i-gövhər tokülə --- (He should be brilliant in speech,)

Məcazi danışa, məcazi gülə --- (He should speak figuratively,)

Tamam sözü müəmmalı gərəkdi --- (And be a politician in discourse.)

Arif ola, eyham ilə söz qana --- (Be quick to understand a hint, howe'er,)

Naməhrəmdən şərm eyleyə, utana --- (Of strangers you should, as a rule, beware,)

Saat kimi meyli Haqq'a dolana --- (And like a clock advance to what is fair.)

Doğru qəlbi, doğru yolu gərəkdi --- (True heart and word of honour you must have.)

Ələsgər haqq sözün isbatın verə --- (Ələsgər will prove his assertions,)

Əməlin mələklər yaza dəftərə --- (Angels will record his deeds,)

Her yanı istese baxanda göre --- (Your glance should be both resolute and pure,)

Teriqetde bu sevdalı gerekdi --- (You must devote himself to righteous path.)

Ashik stories (dastan)

[edit]

İlhan Başgöz was the first to introduce the word hikaye into the academic literature to describe ashik stories.[28] According to Başgöz, hikaye cannot properly be included in any of the folk narrative classification systems presently used by Western scholars. Though prose narrative is dominant in a hikaye, it also includes several folk songs. These songs, which represent the major part of Turkish folk music repertory, may number more than one hundred in a single hekaye, each having three, five or more stanzas.[29]

As the art of ashik is based on oral tradition, the number of ashik stories can be as many as the ashiks themselves. Throughout the centuries of this tradition, many interesting stories and epics have thrived, and some have survived to our times. The main themes of the most ashik stories are worldly love or epics of wars and battles or both.

In the following we present a brief list of the most famous hikayes:[30]

- Shah Ismail, the founder of the Safavid empire, is the protagonist of a major hikaye. Despite the apparent basis in history, Shah Ismail's hikaye demonstrates a remarkable transformative ability. Feared as a ruthless despot during his lifetime, Shah Ismail becomes a poetic maestro in the hikaye, with his sword replaced by his saz, which is the weapon of choice for Shah Ismail's new persona of folk hero.[31]

- The Warrior of The North. A Romantic Action Epic about bard named ashik in Constantinople in the 16th Century where he faces political and military problems and saves many people. In the end, he marries his soul mate, Nuur, but dies the same day in an attempt to save her from Hardun The Evil.

- The Epic of Köroğlu is one of the most widespread of the Turkic hikayes. It is shared not only by nearly all Turkic peoples, but also by some non-Turkic neighboring communities, such as the Armenians, Georgians, Kurds, Tajiks, and Afghans. Although the hikaye's path of transmission is not yet fully understood, most researchers agree that it originated in the south Caucasus region, most likely Azerbaijan.[32] In the Azeri version, the epic combines the occasional romance with Robin Hood-like chivalry. Köroğlu, is himself an ashik, who punctuates the third-person narratives of his adventures by breaking into verse: this is Köroğlu. This popular story has spread from Anatolia to the countries of Central Asia somehow changing its character and content.[8] Azerbaijani composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov has created an opera by this name, using the ashik stories and masterfully combined some ashik music with this major classical work.

- Ashiq Qərib, Azeri epic, made famous by Mikhail Lermontov, is another major story of a wandering ashik who began his journeys with worldly love and attains wisdom by traveling and learning then achieving sainthood. The story of Ashiq Qərib has been the main feature of a movie with the same name by director and producer Sergei Parajanov.[33] In early 1980s Aşıq Kamandar narrated and sang the story in a one-hour-long TV program, the cosset record of which was widely distributed in Iranian Azerbaijan and had a key impact on the revival of ashug music.

- Aşıq Valeh is the story of a debate between Aşıq Valeh[34] (1729–1822) and Aşıq Zərniyar. Forty ashiks have already lost the debate to Aşıq Zərniyar and have been imprisoned. Valeh, however, wins the debate, frees the jailed ashiks and marries Zərniyar.

In order to stay in the profession and defend their reputation ashiks used to challenge each other by indulging in verbal duelings, which were held in public places. In its simplest form one ashik would recite a riddle by singing and the other had to respond by means of improvisation to the verses resembling riddles in form. Here is an example:[35]

| The first ashik | The second ashik |

|---|---|

| Tell me what falls to the ground from the sky? | Rain falls down to the ground from the sky |

| Who calms down sooner of all? | A child calms down sooner of all. |

| What is passed from hand to hand? | Money is passed from hand to hand |

| The second ashik | Shik |

|---|---|

| What remains dry in water? | Light does not become wet in water |

| Guess what does not become dirty in the ground? | Only stones at the pier remain clean. |

| Tell me the name of the bird living alone in the nest | The name of the bird living in its nest in loneliness is heart. |

Famous ashiks

[edit]21st century

[edit]- Changiz Mehdipour, born in Sheykh Hoseynlu, has significantly contributed to the revival and development of ashik music. His book on the subject[36] attempts to adapt the ashik music to the artistic taste of the contemporary audience.

- Samira Aliyeva, born in Baku (1981), is a popular professional ashik who teaches at the Azerbaijan State University of Culture and Art. She is committed to the survival of the ashik tradition.[37]

- Zulfiyya Ibadova, born in 1976, is a passionate and vibrant performer with a strong individual style. She has written a great deal of original music and lyrics, and likes combining the Saz with other instruments.[37]

- Fazail Miskinli, born in 1972, is a master Saz player. He teaches at the Azerbaijan State University of Culture and Art.[38]

20th century

[edit]- Ali Ekber Chichek, Ashik Ibreti, Ashik Khanlar, Ashik Mubarak Yaafar, Muhlis Akarsu, Ashig Adalet, Ashik Daimi, Davut Sulari, Ashig Hossein Bozalganly, Ashig Hossein Sarajly, Ashig Mikayil Azafly, Ashig Emrah, Ashik Seyit Meftuni

- Neshet Ertash, was born in 1938 in Kirshehir, and started playing baglama since he was 5. He died on 25 September 2012 in Izmir.[39] The opening quatrain of his composition, Yalan Dünya, is as the following:[40]

Hep sen mi ağladın hep sen mi yandın, --- (Did you cry all the time, did you burn all the time?)

Ben de gülemedim yalan dünyada --- (I couldn't smile too in untrue world)

Sen beni gönlümce mutlu mu sandın --- (Did you think I was happy with my heart)

Ömrümü boş yere çalan dünyada. --- (In the world which stole my life in vain")

- Ashig Hossein Javan, born in Oti Kandi in Qareh Dagh, is the legendary ashik who was exiled to Soviet Union due to his revolutionary songs during the brief reign of Azerbaijan People's Government following the World War II.[41] Hoseyn Javan's music, in contrast to the contemporary poetry in Iran, emphasizes on realism and highlights the beauties of real life. One of Hoseyn's songs, with the title "Kimin olacaqsan yari, bəxtəvər?", is among the most famous ashugh songs.

- Kamandar Afandov was born in 1932 in Georgia. In early eighties Kamndar performed shortened version of famous hikayes intended for contemporary audience. These performances were effective in the revival of ashik music.[42]

- Rasool Ghorbani, recognized as the godfather among the masters of ashugh music, was born in 1933 in AbbasAbad. Rasool started his music career in 1952 and by 1965 was an accomplished ashik. Rasool had performed in international music festivals held in France, Germany, the Netherlands, England, Japan, China, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Austria, Australia, Azerbaijan, Serbia, Turkey and Hungary.[43][44] Rasool has been awarded highest art awards of Iran,[45] and will be honored by government during the celebration for his 80th birthday.[46]

- Ashik Mahzuni Sherif,(17 November 1940 – 17 May 2002), was a folk musician, ashik, composer, poet, and author from Turkey.[47] His had an undeniable contribution in popularizing ashik music in intellectual circles.[48] The opening quatrain of his composition, İşte gidiyorum çeşm-i siyahım, is as the following:[49]

İşte gidiyorum çeşm-i siyahım --- (That's it, I go my black eyed)

Önümüze dağlar sıralansa da --- (Despite mountains ranked before us)

Sermayem derdimdir servetim ahım --- (My capital is my sorrow, my wealth is my trouble)

Karardıkça bahtım karalansa da --- (Withal my blacken fortune darkened")

- Ashik Veysel (25 October 1894 – 21 March 1973). The opening quatrain of his composition, Kara Toprak ("Black earth"), is as the following:[50]

Dost dost diye nicesine sarıldım --- (I expected for many people to be real friends)

Benim sâdık yârim kara topraktır --- (My faithful beloved is black soil)

Beyhude dolandım boşa yoruldum --- (I wandered around with no end, I got tired for nothing)

Benim sâdık yârim kara topraktır --- (My faithful beloved is black soil")

19th century

[edit]- Ashik Summani, Ashig Aly, Molla Juma, Ashig Musa,

- Ashiq Basti (1836–1936), is one of the most outstanding female representatives of the art of Ashig in nineteenth century Azerbaijan. She was born in the Loh village of the Kalbajar region. She had a deep knowledge of Azerbaijani folk literature and was able to recite poems of her own at these folk ceremonies. She also learned to play the saz. Basti was known to be an active member of 'Gurban Bulaghi', a famous literary gathering of her era. She fell deeply in love with a shepherd sometime between the age of seventeen and eighteen. Her first love, however, was killed by a nobleman in her presence. Having helplessly witnessed this scene, Basti was thrown into a state of mental turmoil by this tragic incident. In her poems, Basti refers to her sweetheart as Khanchoban. In her lifetime, an epic story called 'Basti and Khanchoban' was created to deal with her ill-fated love. She avenges the nobleman who had killed her beloved by cursing him in her poems. Basti lost her eyesight from her endless weeping and she grew old well before her time. She was called 'Blind Basti' and a saying was created about her: 'Even the stone was crying when Basti cried'. However, she lived a long life and died in 1936, at the age of one hundred.[51]

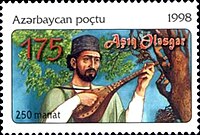

- Ashig Alasgar, perhaps the most renowned Azerbaijani ashik of all ages, was born in 1821 in Gegharkunik Province (Գեղարքունիքի մարզ) of the present day Armenia to an impoverished family. At the age of 14 he was employed as a servant boy and worked for five years, during which fell in love with his employer's daughter, Səhnəbanı. The girl was married off to her cousin and Alasgar was sent home. This failed love urged young Alasgar to buy a saz and seek apprenticeship with Ashik Ali for five years. He emerged as an accomplished ashik and poet and in 1850, unwillingly, defeated his master in a verbal dueling. The rest of Alasgar's productive life was spent training ashiks and composing songs until his death in 1926.[52] Here, we present the opening verses of one of Alasgar's finest compositions, titled Deer (Jeyran).[53] The song has been recently performed by Azerbaijan's beloved traditional singer Fargana Qasimova. Alim Qasimov offers the following commentary on this popular song: "In Azerbaijan, jeyran refers to a kind of deer that lives in the mountains and the plains. They’re lovely animals, and because their eyes are so beautiful, poets often use this word. There are many girls named Jeyran in Azerbaijan. We hope that when listeners hear this song, they’ll get in touch with their own inner purity and sincerity."[54]

Durum dolanım başına, --- (Let me encircle you with love,)

Qaşı, gözü qara, Ceyran! --- (Your black eyes and eyebrows, Jeyran.)

Həsrətindən xəstə düşdüm, --- (I have fallen into the flames of longing,)

Eylə dərdə çara, Ceyran! --- (Help me to recover from this pain, Jeyran".)

.......

- Jivani (Armenian: Ջիվանի, 1846–1909), born Serob Stepani Levonian (Սերոբ Ստեփանի Լևոնյան), was an Armenian ashugh (or gusan) and poet.[55] Jivani's compositions mostly deal with social issues. An example:[56]

THE mournful and unhappy days, like winter, come and go.

We should not be discouraged, they will end, they come and go.

Our bitter griefs and sorrows do not tarry with us long;

Like customers arrayed in line, they come, and then they go. ...

18th century

[edit]- Sayat-Nova

- Khasta Qasim, (1684–1760) was one of the most popular folk poets in Azerbaijan. Khasta, which he chose for a pen-name, means "one in pain".

- Dadaloğlu

- Zarnigar Derbentli

17th century

[edit]- Naghash Hovnatan was an Armenian poet, ashugh, painter, and founder of the Hovnatanian artistic family. He was born in 1661 in the town of Shorot, Nakhijevan. He is considered the founder of the new Armenian minstrel school, following medieval Armenian lyric poetry.[57]

- Kul Nesîmî, Aşıq Abdulla, Sarı Aşıq

- Karacaoğlan is a 17th-century Ottoman folk poet and ashik, who was born around 1606 and died around 1680. The opening quatrain of his composition, Elif, is as the following:[58]

incecikten bir kar yağar, --- (With its tender flakes, snow flutters about,)

Tozar Elif, Elif deyi... --- (Keeps falling, calling out "Elif… Elif…”)

Deli gönül abdal olmuş, --- (This frenzied heart of mine wanders about)

Gezer Elif, Elif deyi... --- (Like minstrels, calling out "Elif… Elif…”)

- Aşıq Ümer (1621—1707) medieval Crimean Tatar poet from Kezlev. He wrote mainly lyric poems and greatly influenced the later ashiks.

- Ashik Abbas Tufarganly was born in the late 16th century in Azarshahr. According to a popular ashik hikaye, known as Abbas və Gülgəz, he was a love rival of King Abbas. The facts about Ashik Abbas's life are mixed with the myths of the said hikaye. Ashik Abbas's compositions have survived and are still song by contemporary ashiks. A famous song starts as the following:[59][60]

Ay həzarət, bir zamana gəlibdir, --- (Oh brothers and sisters, what have we come to:)

Ala qarğa şux tərlanı bəyənməz --- (The jay hates the eagle as never before.)

Başına bir hal gelirse canım, --- If something happens to you,

Dağlara gel dağlara, --- Come to the mountains,

Seni saklar vermez ele canım, --- She will embrace you as her own,

Seni saklar vermez ele. --- Never hands you in to the strangers.

........

16th century

[edit]- Shah Ismail Khatai, (1485–1524) was the founder of the Safavid dynasty (1502–1736). Writing under the pen name of

Khatai, he produced a large volume of lyric poetry in Azerbaijani language. Khatai's poetry is graceful and polished and his language closely approaches to folk idiom:[61]

Winter's shaken off, and spring arrives! --- Rosebuds waken, garden plot revives,

Birds all trill in aching harmony,--- Love's a thrilling flame, disturbing me.

Earth is dressed in furry, downy green, --- Whispers press the silence once serene, .......

- Aşıq Qərib

- Nahapet Kuchak (Armenian: Նահապետ Քուչակ) (died 1592) was an Armenian medieval poet, considered one of the first ashughs.[62] He is best known for his hairens (հայրեն), "couplets with a single coherent theme."[63] Kuchak was probably born in the village of Kharakonis, near the city of Van.[64] He later married a woman named Tangiatun. The poet lived his entire life near the Lake Van area until his death in 1592. Kuchak was buried in the cemetery of Kharakonis St. Theodoros Church and his grave became pilgrimage site.[65]

- Pir Sultan Abdal (ca. 1480–1550) was a Turkish Alevi poet and ashik. During the time, Pir Sultan Abdal with the villagers, went against injustice, and was hanged by the Sivas governor Hızır pasha, who was once his comrade.[66] The opening quatrain of his composition, THE ROUGH MAN, is as the following:[67]

Dostun en güzeli bahçesine bir hoyrat girmiş, --- (The rough man entered the lover's garden)

Korudur hey benli dilber korudur --- (It is woods now, my beautiful one, it is woods,)

Gülünü dererken dalını kırmış --- (Gathering roses, he has broken their stems)

Kurudur hey benli dilber kurudur --- (They are dry now, my beautiful one, they are dry)

- Ashiq Qurbani was born in 1477 in Dirili. He was a contemporary of Shah Ismail and may have served as the court musician. His compositions were handed down as gems of oral art from generation to generation and constitute a necessary repertoire of every ashik. A famous qushma, titled Violet, starts as the following:[38][68]

Başina mən dönüm ala göz Pəri, --- (O my dearest, my love, my beautiful green-eyed Pari)

Adətdir dərələr yaz bənəvşəni. --- (Custom bids us pluck violets when spring days begin)

Ağ nazik əlinən dər dəstə bağla, --- (With your tender white hand gather a nosegay,)

Tər buxaq altinə düz bənəvşəni... --- (Pin it under your dainty chin.....)

15th century

[edit]- Kaygusuz Abdal, was born in the late 14th century into a noble and aristocratic family of the Anatolian province of Teke and died in 1445. He traveled throughout the Middle East and eventually came to Cairo where he founded a Bektashi convent. Kaygusuz's poetry is among the strangest expressions of Sufism. He does not hesitate to describe in great detail his dreams of good food, nor does he shrink from singing about his love adventures with a charming young man. A tekerleme by Kaygusuz sounds like a perfect translation of a nursery rhyme:[69]

kaplu kaplu bağalar kanatlanmiş uçmağa.. ---- The turturturtles have taken wings to fly ...

- Imadaddin Nasimi, born 1369 and skinned alive in Aleppo in 1417, was an Azerbaijani or Iraqi Turkmen Ḥurūfī poet. His quatrains are very close to ashik bayati.[70]

13th century

[edit]

- Yunus Emre (1240–1321) was one of the first Turkish poets who wrote poems in his mother tongue rather than Persian or Arabic, which were the writing medium of the era. Emre was not literally an ashik, but his undeniable influence on the evolution of ashik literature is being felt to the present times.[71] The opening quatrain of his composition, Bülbül Kasidesi Sözleri, is as the following:[72]

İsmi sübhan virdin mi var? --- (is The Father's name your mantra?)

Bahçelerde yurdun mu var? --- (are those gardens your home?)

Bencileyin derdin mi var? --- (is your plight just as mine?)

Garip garip ötme bülbül --- (don't sing in sorrow nightingale)

See also

[edit]- Ashiqs of Azerbaijan

- Aqyn

- Bakshy

- Dengbêj

- Gusans

- Khananda

- Ishq

- Ashik Kerib and Ashiq Qarib

- Epic of Koroghlu

- Epic of Manas

- The Color of Pomegranates

- List of Turkic-languages poets

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ a b c The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 2. Routledge. 2013. ISBN 978-1136095948.

- ^ Russell, James R. (2018). "43. From Parthia to Robin Hood: The Epic of the Blind Man's Son". In DiTommaso, Lorenzo; Henze, Matthias; Adler, William (eds.). The Embroidered Bible: Studies in Biblical Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha in Honour of Michael E. Stone. Leiden: Brill. pp. 878–898. ISBN 9789004355880. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ a b Ziegler, Susanne (1997). "East Meets West - Urban Musical Styles in Georgia". In Stockmann, Doris; Koudal, Henrik Jens (eds.). Historical Studies on Folk and Traditional Music: ICTM Study Group on Historical Sources of Folk Music, Conference Report, Copenhagen, 24–28 April 1995. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 159–161. ISBN 8772894415.

- ^ a b Shidfar, Farhad (5 February 2019). "Azerbaijani Ashiq Saz in West and East Azerbaijan Provinces of Iran". In Özdemir, Ulas; Hamelink, Wendelmoet; Greve, Martin (eds.). Diversity and Contact Among Singer-Poet Traditions in Eastern Anatolia. Ergon Verlag. ISBN 978-3956504815.

- ^ a b Yang, Xi (5 February 2019). "History and Organization of the Anatolian Ašuł/Âşık/Aşıq Bardic Traditions". In Özdemir, Ulas; Hamelink, Wendelmoet; Greve, Martin (eds.). Diversity and Contact Among Singer-Poet Traditions in Eastern Anatolia. Ergon Verlag. ISBN 978-3956504815.

- ^ Kardaş, Canser (5 February 2019). "The Legacy of Sounds in Turkey: Âşıks and Dengbêjs". In Özdemir, Ulas; Hamelink, Wendelmoet; Greve, Martin (eds.). Diversity and Contact Among Singer-Poet Traditions in Eastern Anatolia. Ergon Verlag. ISBN 978-3956504815.

- ^ Babayan, Kathryn; Pifer, Michael (7 May 2018). An Armenian Mediterranean: Words and Worlds in Motion. Springer. pp. 200–201. ISBN 978-3319728650.

- ^ a b Colin P. Mitchell (Editor), New Perspectives on Safavid Iran: Empire and Society, 2011, Routledge, 90–92

- ^ M. Heydari-Malayeri On the origin of the word ešq

- ^ a b Köprülü, Mehmet Fuat (2006). Early Mystics in Turkish Literature. Psychology Press. ISBN 0415366860.

- ^ Studies on the Soviet Union - 1971, Volume 11 - Page 71

- ^ "DASTAN GENRE IN CENTRAL ASIA – ESSAYS ON CENTRAL ASIA by H.B. PAKSOY – CARRIE Books". Vlib.iue.it. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ G. Lewis (translator), The Book of Dede Korkut, Penguin Classics(1988)

- ^ AlMAD, Y. S. (2006). LITERARY INFLUENCE. Early Mystics in Turkish Literature (PDF). pp. lii–lvi.

- ^ Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu (Editor), Culture and Learning in Islam, 2003, p. 282

- ^ "Atlas of traditional music of Azerbaijan". Atlas.musigi-dunya.az. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Köprülü, Mehmet Fuat (1962). Türk Saz Şairleri I. Ankara: Güven Basımevi. p. 12.

- ^ Rouben Paul Adalian, Historical Dictionary of Armenia, 2010, p.452.

- ^ Albright, C.F. "ʿĀŠEQ". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Today.az. Azerbaijan’s ashik art included into UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage. 1 October 2009

- ^ A. Oldfield Senarslan, Women Aşiqs of Azerbaijan: Tradition and Transformation, 2008, ProQuest LLC., p. 44

- ^ "ATLAS of Plucked Instruments – Middle East". ATLAS of Plucked Instruments. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Kipp, N. (2012). Organological geopolitics and the Balaban of Azerbaijan: comparative musical dialogues concerning a double-reed aerophone of the post-Soviet Caucasus (Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign).

- ^ "Ashiq poems- Proverbs and sayings". Azerbaijans.com. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ "Poetry genres". Azerbaijans.com. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ [1] Archived 5 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Madatli, Eynulla (2010). Poetry of Azerbaijan (PDF). Embassy of the Republic of Azerbaijan in Islamabad. p. 110. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ Baṣgöz, I. (1967). Dream Motif in Turkish Folk Stories and Shamanistic Initiation. Asian Folklore Studies, 26(1), 1–18.

- ^ Basgoz, I. (1970). Turkish Hikaye-Telling Tradition in Azerbaijan, Iran. Journal of American Folklore, 83(330), 394.

- ^ Sabri Koz, M. "Comparative Bibliographic Notes on Karamanlidika Editions of Turkish Folk Stories" (PDF). Harrassowitz Verlag.

- ^ Gallagher, Amelia (2009). "The Transformation of Shah Ismail Safevi in the Turkish Hikaye". Journal of Folklore Research. 46 (2): 173–196. doi:10.2979/jfr.2009.46.2.173. S2CID 161620767.

- ^ "The Persianization of Koroglu : Banditry and Royalty in Three Versions of the Koroglu Destan" (PDF). Nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ James Steffen, The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov, 2013, Chap. 8

- ^ Azad Nabiyev, Azarbaycan xalq adabiyyati, 2006, Page 213

- ^ ÜSTÜNYER, Ýlyas (2009). "Tradition of the Ashugh Poetry and ashik in Georgia" (PDF). IBSU Scientific Journal. 3. 1: 137–149. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ خبرگزاری باشگاه خبرنگاران | آخرین اخبار ایران و جهان | (26 October 1390). "مجموعه كتاب مكتب قوپوز در زمینه موسیقی عاشیقی منتشر شد". fa. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Oldfield Senarslan, Anna. "It's time to drink blood like its Sherbet": Azerbaijani women ashiqs and the transformation of tradition" (PDF). Congrès des musiques dans le monde de l'islam. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Neşet Ertaş". Biyografi.net. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Untrue World". Lyricstranslate.com. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Ashugh Hoseyn Javan". Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "OZAN DÜNYASI" (PDF). 2012. pp. 17–43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Rasool, The prominent figure of Azeri music". Gunaz.tv. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "سازمان فرهنگی هنری – عاشيق رسول قرباني". Honar.tabriz.ir. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Ashik Rasool was awarded for achievements". Khabarfarsi.com. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "تولد 80 سالگی "عاشیق رسول" در فرهنگسرای نیاوران برگزار میشود". fa. 8 December 1392. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014.

- ^ "Bouwgids.com". 31 August 2021. Archived from the original on 20 April 2008.

- ^ "Aşık Mahzuni Şerif". Mahzuniserif.com. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Gulalys. "That's it, I go my black eyed". Lyricstranslate.com. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Black soil/earth". Lyricstranslate.com. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Naghiyeva, Shahla; Amirdabbaghian, Amin; Shunmugam, Krishnavanie (16 December 2019). "Ashik Basti: My Saz Wails for My Beloved". Southeast Asian Review of English. 56 (2): 116–138. doi:10.22452/sare.vol56no2.10.

- ^ Aşiq Ələsgər Əəsərləri (PDF). Bakı: ŞƏRQ-QƏRB. 2004. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "AŞIQ ƏLƏSGƏR GƏRAYLI LAR". Azeritest.com/. Archived from the original on 23 June 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Alim and Fargana Qasimov: Spiritual Music of Azerbaijan". Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Michnadar, by Agop Jack Hacikyan, Gabriel Basmajian, Edward S. Franchuk, Nourhan Ouzounian – 2002 – Page 1036

- ^ Stone Blackwell, Alice. "UNHAPPY DAYS". ArmenianHouse.org. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Basmajian, Gabriel; Franchuk, Edward S.; Ouzounian, Nourhan (2000). Hacikyan, Agop Jack (ed.). The Heritage of Armenian Literature: From the Sixth to the Eighteenth Century, Volume II. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 867–872. ISBN 0814330231.

- ^ "Translation of "Elif" by Badem from Turkish to English". Lyricstranslate.com. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Bəyənməz". Archived from the original on 2 May 2014.

- ^ Madatli, Eynulla (2010). Poetry of Azerbaijan (PDF). Embassy of the Republic of Azerbaijan in Islamabad. p. 80. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Madatli, Eynulla (2010). Poetry of Azerbaijan (PDF). Embassy of the Republic of Azerbaijan in Islamabad. p. 67. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Նահապետ Քոչւակ". ArmenianHouse.org. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ^ Roland Greene; Stephen Cushman; Clare Cavanagh; Jahan Ramazani; Paul F. Rouzer (2012). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics: Fourth Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 84. ISBN 9780691154916.

- ^ "Nahapet Kuchak". Writers.am. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ^ Holding, Nicholas. Bradt Armenia: With Nagorno Karabagh (3rd ed.). Chalfont St. Peter, Bucks: Bradt Travel Guides. p. 44. ISBN 9781841623450.

- ^ "The Pir Sultan Abdal play". Hackneyempire.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "THE ROUGH MAN ENTERED THE LOVER'S GARDEN". Siir.gen.tr. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Madatli, Eynulla (2010). Poetry of Azerbaijan (PDF). Embassy of the Republic of Azerbaijan in Islamabad. p. 75. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Kaygusuz Abdal Sultan: Poetry, Biography". bektashiorder.com. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Azerbaijan". Azerbaijans.com. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ AlMAD, Y. S. (2006). LITERARY INFLUENCE. Early Mystics in Turkish Literature (PDF). pp. 367–368. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Psalm of The Nightingale". Retrieved 17 November 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Mignon, Laurent (2015). "Ashugh". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

External links

[edit]- Details of the film Ashik Kerib by Parajanov

- Women Performers of Legend and Folk Poetry

- The Poet Minstrels of Azerbaijan

- "ĀŠEQ" (Iranica Encyclopedia)

- "Asik" in Turkish Oral Narrative Archived 29 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine