Delamanid

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Deltyba |

| Other names | OPC-67683 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | UK Drug Information |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | ≥99.5% |

| Metabolism | in plasma by albumin, in liver by CYP3A4 (to a lesser extent) |

| Elimination half-life | 30–38 hours |

| Excretion | not excreted in urine[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.348.783 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

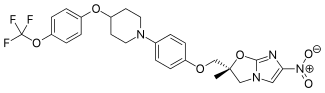

| Formula | C25H25F3N4O6 |

| Molar mass | 534.492 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Delamanid is sold under the brand name Deltyba, is a medication used to treat tuberculosis.[2] Specifically it is used, along with other antituberculosis medications, for active multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.[2] It is taken by mouth.[2]

There are common side effects which include headache, dizziness, and nausea.[3] Other side effects include QT prolongation.[2] Delamanid works by blocking the manufacture of mycolic acids thus destabilising the bacterial cell wall.[4] It is in the nitroimidazole class of medications.[5]

Delamanid was approved for medical use in 2014 in Europe, Japan, and South Korea.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7] As of 2016 the Stop TB Partnership had an agreement to get the medication for US$1,700 per six month for use in more than 100 countries.[8]

Medical uses

[edit]Delamanid is used, along with other antituberculosis medications, for active multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.[2]

Adverse effects

[edit]Common side effects include headache, dizziness, and nausea.[3] Other side effects include QT prolongation.[2] Use in pregnancy has not been extensively studied, but there have been reports of success[9] and it is currently recommended as part of the standard treatment regimen for pregnant women with rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa.[10]

Interactions

[edit]Delamanid is metabolised by the liver enzyme CYP3A4; therefore strong inducers of this enzyme can reduce its effectiveness.[11]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Delamanid is activated in the mycobacterium by deazaflavin-dependent nitroreductase (Ddn), an enzyme which uses dihydro-F420 (reduced form), into nitric oxide and a highly reactive metabolite. This metabolite attacks the synthesis enzyme DprE2, which is important for the synthesis of cell wall arabinogalactan, to which mycolic acid would be attached. This mechanism is shared with pretomanid. Clinical isolates resistant to this drug tend to have mutations in the biosynthetic pathway for Coenzyme F420.[12]

History

[edit]In phase II clinical trials, the drug was used in combination with standard treatments, such as four or five of the drugs ethambutol, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, rifampicin, aminoglycoside antibiotics, and quinolones. Healing rates (measured as sputum culture conversion) were significantly better in patients who additionally took delamanid.[13][14]

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended conditional marketing authorization for delamanid in adults with multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis without other treatment options because of resistance or tolerability. The EMA considered the data show that the benefits of delamanid outweigh the risks, but that additional studies were needed on the long-term effectiveness.[15]

Society and culture

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (March 2020) |

The medication was not readily available globally as of 2015. It was believed that pricing will be similar to bedaquiline, which for six months is approximately US$900 in low income countries, US$3,000 in middle income countries, and US$30,000 in high income countries.[2] As of 2016 the Stop TB Partnership had an agreement to get the medication for US$1,700 per six month.[8]

References

[edit]- ^ "Deltyba (delamanid): Summary of Product Characteristics. 5.2. Pharmacokinetic Properties" (PDF). Otsuka Novel Products GmbH. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g World Health Organization (2015). The selection and use of essential medicines. Twentieth report of the WHO Expert Committee 2015 (including 19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and 5th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children). Geneva: World Health Organization. pp. 30–1. hdl:10665/189763. ISBN 9789241209946. ISSN 0512-3054. WHO technical report series;994.

- ^ a b Smith MR, Accinelli A, Tejada FR, Kharel MK (2016). "Drugs Used in Tuberculosis and Leprosy". In Ray SD (ed.). Side Effects of Drugs Annual: A Worldwide Yearly Survey of New Data in Adverse Drug Reactions. Elsevier. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-444-63889-2. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- ^ Blair HA, Scott LJ (January 2015). "Delamanid: a review of its use in patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis". Drugs. 75 (1): 91–100. doi:10.1007/s40265-014-0331-4. PMID 25404020. S2CID 34541500.

- ^ Alves de Oliverira TS, da Sliva Rabello MC (2017). "Vaccines Against Tuberculosis". In de Paiva Cavalcanti M, Pereira VR, Dessein AJ (eds.). Tropical Diseases: An Overview of Major Diseases Occurring in the Americas. Bentham Science Publishers. p. 461. doi:10.2174/9781681085876117010022. ISBN 978-1-68108-587-6.

- ^ Fischer J (2016). Successful Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 139. ISBN 978-3-527-34115-3. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ a b "Stop TB Partnership | "Stop TB Partnership's Global Drug Facility jumpstarts access to new drugs for MDR-TB with innovative public-private partnerships". www.stoptb.org. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ Acquah R, Mohr-Holland E, Daniels J, Furin J, Loveday M, Mudaly V, et al. (May 2021). "Outcomes of Children Born to Pregnant Women With Drug-resistant Tuberculosis Treated With Novel Drugs in Khayelitsha, South Africa: A Report of Five Patients". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 40 (5): e191–e192. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000003069. PMC 8043512. PMID 33847295.

- ^ "Clinical Management of Rifampicin-Resistant Tuberculosis: Updated Clinical Reference Guide" (PDF). Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. September 2023.

- ^ "Delamanid: Neuer Wirkstoff gegen multiresistente TB". Pharmazeutische Zeitung (in German). 9 May 2014. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ Abrahams KA, Batt SM, Gurcha SS, Veerapen N, Bashiri G, Besra GS (June 2023). "DprE2 is a molecular target of the anti-tubercular nitroimidazole compounds pretomanid and delamanid". Nature Communications. 14 (1): 3828. Bibcode:2023NatCo..14.3828A. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39300-z. PMC 10307805. PMID 37380634.

- ^ Spreitzer H (18 February 2013). "Neue Wirkstoffe – Bedaquilin und Delamanid". Österreichische Apothekerzeitung (in German) (4/2013): 22.

- ^ Gler MT, Skripconoka V, Sanchez-Garavito E, Xiao H, Cabrera-Rivero JL, Vargas-Vasquez DE, et al. (June 2012). "Delamanid for multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 366 (23): 2151–2160. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1112433. PMID 22670901.

- ^ "European Medicines Agency recommends two new treatment options for tuberculosis". European Medicines Agency. 22 November 2013. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.