Sexuality of Abraham Lincoln

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal Political 16th President of the United States First term Second term Presidential elections Speeches and works

Assassination and legacy  |

||

The sexuality of Abraham Lincoln has been the topic of historical speculation and research. No such discussions have been documented during or shortly after Lincoln's lifetime; however, in recent decades (circa 1995),[1] some writers have discussed purported evidence that he may have been homosexual.

Mainstream historians generally hold that Lincoln was heterosexual,[2][3] noting that the historical context explains any of the supposed evidence.[4] Lincoln had romantic ties with women, and he had four children in an enduring marriage to a woman.[5]

Historical scholarship and debate

[edit]Commentary on President Abraham Lincoln's sexuality has been documented since the early 20th century. Attention to the sexuality of public figures has been heightened since the gay rights movement in the late 20th century. In his 1926 biography of Lincoln, Carl Sandburg alluded to the early relationship of Lincoln and his friend Joshua Fry Speed as having "a streak of lavender, and spots soft as May violets". "Streak of lavender" was period slang for an effeminate man and later connoted homosexuality.[6] Sandburg did not elaborate on this comment.[7] Historian and psychoanalyst Charles B. Strozier believes that it is unlikely for Sandburg to have used that phrase with homosexual implications, suggesting that he instead used the term to note "Speed's and Lincoln's softer, more vulnerable sides, which shielded their vigorous masculinity".[8]

In 1999, playwright and activist Larry Kramer claimed that he had uncovered previously unknown documents while conducting research for his work-in-progress, The American People: A History.[9] Some were allegedly found hidden in the floorboards of the old store once shared by Lincoln and Joshua Speed. According to Kramer, the unseen documents reportedly provided explicit details of a relationship between Lincoln and Speed, and they currently reside in a private collection in Davenport, Iowa.[10] Their authenticity, however, has been called into question by historians such as Gabor Boritt, who wrote, "Almost certainly this is a hoax."[11] C. A. Tripp also expressed his skepticism over Kramer's discovery, writing, "Seeing is believing, should that diary ever show up; the passages claimed for it have not the slightest Lincolnian ring."[12]

In 2005, C. A. Tripp's book, The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln, was posthumously published. Tripp was a sex researcher, a protégé of Alfred Kinsey, and was gay. He began writing The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln with Philip Nobile, but they had a falling out. Nobile later accused Tripp's book of being fraudulent and distorted.[13][14]

Time magazine addressed the book as part of a cover article by Joshua Wolf Shenk, author of Lincoln's Melancholy: How Depression Challenged a President and Fueled His Greatness. Shenk dismissed Tripp's conclusions, saying that arguments for Lincoln's homosexuality were "based on a tortured misreading of conventional 19th century sleeping arrangements".[15] But historian Michael B. Chesson said that Tripp's work was significant, commenting that "any open-minded reader who has reached this point may well have a reasonable doubt about the nature of Lincoln's sexuality".[16]

In 2009, Charles Morris critically analyzed the academic and popular responses to Tripp's book, arguing that much of the negative response by the "Lincoln Establishment" reveals as much rhetorical and political partisanship as that of Tripp's defenders.[17] In an earlier 2007 essay, Morris argues that in the wake of playwright Larry Kramer's "outing" of Lincoln, the Lincoln Establishment engaged in "mnemonicide", or the assassination of a threatening counter-memory. He put in this category what he called the methodologically flawed but widely appropriated case against the "gay Lincoln thesis" by David Herbert Donald in his book, We Are Lincoln Men.[18]

Lincoln's stepmother, Sarah Bush Lincoln, commented that he "never took much interest in the girls". However some accounts of Lincoln's contemporaries suggest that he had a strong but controlled passion for women.[19] Lincoln was allegedly devastated over the 1835 death of Ann Rutledge. While some historians have questioned whether he had a romantic relationship with her, historian John Y. Simon reviewed the historiography of the subject and concluded that "Available evidence overwhelmingly indicates that Lincoln so loved Ann that her death plunged him into severe depression. More than a century and a half after her death, when significant new evidence cannot be expected, she should take her proper place in Lincoln biography."[20]

In her book Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, historian Doris Kearns Goodwin argues:

Their intimacy is more an index to an era when close male friendships, accompanied by open expressions of affection and passion, were familiar and socially acceptable. Nor can sharing a bed be considered evidence of an erotic involvement. It was common practice in an era when private quarters were a rare luxury.... The attorneys of the Eighth Circuit in Illinois where Lincoln would travel regularly shared beds. (58)

Critics of the hypothesis that Lincoln was homosexual emphasize that Lincoln married and had four children. Scholar Douglas Wilson writes that Lincoln as a young man displayed robustly heterosexual behavior, including telling stories to his friends of his interactions with women.[21]

Lincoln wrote a poem that described a marriage between two men, which included the lines:

For Reuben and Charles have married two girls,

But Billy has married a boy.

The girls he had tried on every side,

But none he could get to agree;

All was in vain, he went home again,

And since that he's married to Natty.

This poem was included in the first edition of the 1889 biography of Lincoln by his friend and colleague William Herndon.[22] It was expurgated from subsequent editions until 1942, when the editor Paul Angle restored it.

Tripp states that Lincoln's awareness of homosexuality and openness in penning this "bawdy poem" "was unique for the time period" and that "any ... nineteen or twenty year-old heterosexual male [would not have been able to write the poem]."[23] Lewis Gannett notes that the poem was "a satirical poem, written to embarrass someone against whom Lincoln held a grudge".[4]

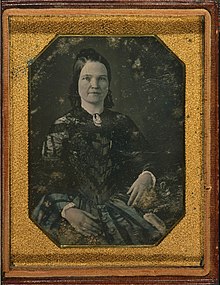

Marriage with Mary Todd Lincoln

[edit]

Lincoln and Mary Todd met in Springfield in 1839 and became engaged in 1840. In what historian Allen Guelzo calls "one of the murkiest episodes in Lincoln's life," Lincoln called off his engagement to Mary Todd. This was at the same time as the collapse of a legislative program he had supported for years, the permanent departure of his best friend, Joshua Speed, from Springfield, Illinois, and the proposal by John Stuart, Lincoln's law partner, to end their law practice.[24] Lincoln is believed to have suffered something approaching clinical depression. In the book Lincoln's Preparation for Greatness: The Illinois Legislative Years, Paul Simon has a chapter covering the period, which Lincoln later referred to as "The Fatal First", or January 1, 1841. That was "the date on which Lincoln asked to be released from his engagement to Mary Todd".[25] Simon explains that the various reasons given for the engagement being broken contradict one another. The incident was not fully documented, but Lincoln did become unusually depressed, which showed in his appearance. Simon wrote that it was "traceable to Mary Todd".[25] During this time, he avoided seeing Mary, causing her to comment that Lincoln "deems me unworthy of notice".[25]

Jean H. Baker, historian and biographer of Mary Todd Lincoln, describes the relationship between Lincoln and his wife as "bound together by three strong bonds—sex, parenting and politics".[26] In addition to the anti–Mary Todd bias of many historians, engendered by William Herndon's (Lincoln's law partner and early biographer) personal hatred of Mrs. Lincoln, Baker discounts historic criticism of the marriage. She says that contemporary historians have a misunderstanding of the changing nature of marriage and courtship in the mid-19th century, and attempt to judge the Lincoln marriage by modern standards.[26] According to the book Lincoln the Unknown, Lincoln chose to spend several months of the year practicing law on a circuit that kept him living separately from his wife.[26]

Baker states that "most observers of the Lincoln marriage have been impressed with their sexuality" and that "male historians" suggest that the Lincolns' sex life ended either in 1853 after their son Tad's difficult birth or in 1856 when they moved into a bigger house, but have no evidence for their speculations. Baker writes that there are "almost no gynecological conditions resulting from childbirth" other than a prolapsed uterus (which would have produced other noticeable effects on Mrs. Lincoln) that would have prevented intercourse, and in the 1850s, "many middle-class couples slept in separate bedrooms" as a matter of custom adopted from the English.[26]

Far from abstaining from sex, Baker suggests that the Lincolns were part of a new development in America of smaller families; the birth rate declined from seven births to a family in 1800 to around 4 per family by 1850. As Americans separated sexuality from childbearing, forms of birth control such as coitus interruptus, long-term breastfeeding, and crude forms of condoms and womb veils, available through mail order, were available and used. The spacing of the Lincoln children (Robert in 1843, Eddie in 1846, Willie in 1850, and Tad in 1853) is consistent with some type of planning and would have required "an intimacy about sexual relations that for aspiring couples meant shared companionate power over reproduction".[27]

Herndon, Lincoln's law partner and biographer, attests to the depth of Lincoln's love for Ann Rutledge. An anonymous poem about suicide published locally three years after her death is widely attributed to Lincoln.[28][29] In contrast, his courting of Mary Owens was diffident. In 1837, Lincoln wrote to her from Springfield to give her an opportunity to break off their relationship. Lincoln wrote to a friend in 1838: "I knew she was oversize, but now she appeared a fair match for Falstaff".[30]

Relationship with Joshua Speed

[edit]

Lincoln met Joshua Fry Speed in Springfield, Illinois, in 1837, when Lincoln was a successful attorney and member of Illinois' House of Representatives. They lived together for four years, during which time they occupied the same bed during the night (some sources specify a large double bed) and developed a friendship that would last until Lincoln's death.[31] According to some sources, William Herndon[32] and a fourth man also slept in the same room.[33]

Historians such as David Herbert Donald point out that it was not unusual at that time for two men to share a bed due to myriad circumstances, without anything sexual being implied, for a night or two when nothing else was available. Lincoln, who had just moved to a new town when he met Speed, was also at least initially unable to afford his own bed and bedding; however, Lincoln continued sleeping in a bed with Speed for several years.[34] A tabulation of historical sources shows that Lincoln slept in the same bed with at least 11 boys and men during his youth and adulthood.[35]

There are no known instances in which Lincoln tried to suppress knowledge or discussion of such arrangements, and in some conversations, raised the subject himself. Tripp discusses three men at length and possible sustained relationships: Joshua Speed, William Greene, and Charles Derickson. However, in 19th-century America, it was not necessarily uncommon for men to bunk-up with other men, briefly, if no other arrangement were available. For example, when other lawyers and judges traveled "the circuit" with Lincoln, the lawyers often slept "two in a bed and eight in a room".[36] William H. Herndon recalled for example, "I have slept with 20 men in the same room".[37]

In the nineteenth century, most men were probably not conscious of any erotic possibility of bed-sharing, since it was in public. Speed's immediate, casual offer, and his later report of it, suggests that men's public bed-sharing was not then often explicitly understood as conducive to forbidden sexual experiments.[19] In such public arrangements, they would not be alone.

Nevertheless, Katz says that such sleeping arrangements "did provide an important site (probably the major site) of erotic opportunity" if they could keep others from noticing. Katz states that referring to present-day concepts of "homo, hetero, and bi distorts our present understanding of Lincoln and Speed's experiences."[19] He states that, rather than there being "an unchanging essence of homosexuality and heterosexuality," people throughout history "continually reconfigure their affectionate and erotic feelings and acts".[19] He suggests that the Lincoln-Speed relationship fell within a 19th-century category of intense, even romantic man-to-man friendships with erotic overtones that may have been "a world apart in that era's consciousness from the sensual universe of mutual masturbation and the legal universe of 'sodomy,' 'buggery,' and 'the crime against nature'".[19]

Some correspondence of the period, such as that between Thomas Jefferson Withers and James Henry Hammond, may provide evidence of a sexual dimension to some secret same-sex bed-sharing.[38] The fact that Lincoln was open about sharing a bed with Speed is seen by some historians as an indication that their relationship was not romantic.[39] None of Lincoln's enemies hinted at any homosexual implication.[40]

Joshua Speed and Lincoln corresponded about their impending marriages, and Gore Vidal regarded their letters to each other as having evinced a degree of anxiety about being able to perform sexually on their wedding nights that indicated a homosexual relationship had once existed between them.[41] Despite having some political differences over slavery, they remained in touch until Lincoln died, and Lincoln appointed Joshua's brother, James Speed, to his cabinet as Attorney General.[42]

In 2016, historian and psychoanalyst Charles B. Strozier published, Your Friend Forever, A. Lincoln: The Enduring Friendship of Abraham Lincoln and Joshua Speed, in which he examines their relationship. In 1982, Strozier had previously written Lincoln’s Quest for Union, in which there was a chapter that some had taken as support for the Lincoln gay thesis. Strozier concludes that the relationship was not homosexual and that Lincoln was straight.[43]

Relationship with David Derickson

[edit]Captain David Derickson of the 150th Pennsylvania Infantry was Lincoln's bodyguard and companion between September 1862 and April 1863. They shared a bed during the absences of Lincoln's wife, until Derickson was promoted in 1863.[44] Derickson was twice married and fathered ten children. Tripp recounts that, whatever the level of intimacy of the relationship, it was the subject of gossip. Elizabeth Woodbury Fox, the wife of Lincoln's naval aide, wrote in her diary for November 16, 1862, "Tish says, 'Oh, there is a Bucktail soldier here devoted to the president, drives with him, and when Mrs. L. is not home, sleeps with him.' What stuff!"[16] This sleeping arrangement was also mentioned by a fellow officer in Derickson's regiment, Thomas Chamberlin, in the book History of the One Hundred and Fiftieth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, Second Regiment, Bucktail Brigade. Historian Martin P. Johnson states that the strong similarity in style and content of the Fox and Chamberlin accounts suggests that, rather than being two independent accounts of the same events as Tripp claims, both were based on the same report from a single source.[45] David Donald and Johnson both dispute Tripp's interpretation of Fox's comment, saying that the exclamation of "What stuff!" was, in that day, an exclamation over the absurdity of the suggestion rather than the gossip value of it (as in the phrase "stuff and nonsense").[46]

References

[edit]- ^ "Did Washington Hate Gays?". Newsweek. 15 October 1995.

- ^ Baker, Jean (2005). Gannett, Lewis (ed.). Introduction. Simon and Schuster. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-4391-0404-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Media, Participant (2012). Lincoln: A President for the Ages. PublicAffairs. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-61039-264-8.

Some historians have dismissed the claim, saying they misinterpreted such once-common practices as men sharing a bed "while traveling".

- ^ a b Gannett, Lewis (2016). "Straight Abe: Back Like a Bad Penny." The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide 23 (5): 17-20."

- ^ Steers Jr., Edward (2007). "The Gay Lincoln Myth". Lincoln Legends: Myths, Hoaxes, and Confabulations Associated with Our Greatest President. University Press of Kentucky. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-8131-7275-0.

- ^ A. J. Pollock, Underworld Speaks (1935) p 115/2, cited in Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ Philip Nobile, "Don't Ask, Don't Tell, Don't Publish: Homophobia in Lincoln Studies?", GMU History News Network, June 2001

- ^ Strozier, Charles B. (2016). Your Friend Forever, A. Lincoln: The Enduring Friendship of Abraham Lincoln and Joshua Speed. Columbia University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-231-54130-5.

- ^ Kramer, Larry. "Nuremberg Trials for AIDS" Archived 2011-07-25 at the Wayback Machine, The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide. September–October 2006.

- ^ Carol Lloyd "Was Lincoln Gay?", Salon Ivory Tower May 3, 1999

- ^ Gabor Boritt, The Lincoln Enigma: The Changing Faces of an American Icon, Oxford University Press, 2001, p.xiv.

- ^ C.A. Tripp, The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln, pg xxx, Free Press, 2005 ISBN 0-7432-6639-0

- ^ Smith, Dinitia "Finding Homosexual Threads in Lincoln's Legend", December 16, 2004, New York Times

- ^ Nobile, Philip "Honest, Abe?", Weekly Standard, Vol. 10, Issue 17, 17 January 2005

- ^ "The True Lincoln". Time. June 26, 2005. Archived from the original on June 28, 2005. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ a b Michael B. Chesson, "Afterword: 'The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln'," p. 245, Free Press, 2005, ISBN 0-7432-6639-0

- ^ Charles E. Morris III, "Hard Evidence: The Vexations of Lincoln's Queer Corpus", in Rhetoric, Materiality, Politics, ed. Barbara Biesecker and John Louis Lucaites (New York: Peter Lang, 2009): 185-213

- ^ "My Old Kentucky Homo: Abraham Lincoln, Larry Kramer, and the Politics of Queer Memory", Queering Public Address: Sexualities and American Historical Discourse, ed. Charles E. Morris III (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2007): 93-120

- ^ a b c d e Jonathan Ned Katz, Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001. On Lincoln and Speed, see chapter 1, "No Two Men Were Ever More Intimate", pp. 3-25. For more on Lincoln and sexuality see the notes to this chapter.

- ^ Abraham Lincoln and Ann Rutledge Archived 2006-06-22 at the Wayback Machine, John Y. Simon

- ^ Douglas Wilson Honor's Voice: The Transformation of Abraham Lincoln, Vintage Publishing, 1999, ISBN 0-375-70396-9

- ^ Herndon, W. H., Herndon's Lincoln: The True Story of a Great Life. Scituate, MA: Digital Scanning, 2000.

- ^ C.A. Tripp, The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln pg 40-41 Free Press 2005 ISBN 0-7432-6639-0

- ^ Allen C. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President, (1999) pg. 97-98.

- ^ a b c Paul Simon, Lincoln's Preparation for Greatness: The Illinois Legislative Years

- ^ a b c d Jean H. Baker, "Mary and Abraham: A Marriage" in The Lincoln Enigma, edited by Gabor Boritt, pgs. 49-55

- ^ Baker pg. 50. Baker relies on (page 286, footnote 36) Linda Gordon's Woman's Body, Woman's Right: A Social History of Birth Control (1976) and Janet Brodie's Contraception and Abortion in 19th Century America (1994).

- ^ "The Suicide Poem", The New Yorker, Eureka Dept., Jun 14, 2004

- ^ Library of Congress: Collection Guides (online), Lincoln as Poet

- ^ "Letter, Abraham Lincoln to Mary S. Owens reflecting the frustration of courtship, 16 August 1837". Library of Congress. (Abraham Lincoln Papers)

- ^ Excerpt from D. H. Donald's We are Lincoln Men Simon & Schuster 2003 ISBN 0-7432-5468-6

- ^ Sandburg 1:244

- ^ Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years (1926) 1:244

Richard Brookhiser (Jan 9, 2005). "Richard Brookhiser's NYT Book Review of C.A. Tripp's Gay Lincoln Biography". NYT Book Review – via History News Network.

David H. Donald's We are Lincoln Men, op.cit. - ^ Keneally, Thomas (2002). Abraham Lincoln: A Life. Penguin. Chapter 4. ISBN 978-0670031757.

- ^ Sotos, JG (2008). The Physical Lincoln Sourcebook. Mount Vernon, VA: Mt. Vernon Book Systems.

- ^ Randall, Ruth Painter. Mary Lincoln: Biography of a Marriage. Boston: Little, Brown, 1953. pp 70-71.

- ^ Donald, D.H. Lincoln's Herndon. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1948, pg. 46

- ^ Martin Duberman, "Writhing Bedfellows: 1826 Two Young Men from Antebellum South Carolina's Ruling Elite Share 'Extravagant Delight'", in Salvatore Licata and Robert Petersen, eds., Historical Perspectives on Homosexuality (New York: Haworth Press & Stein & Day, 1981), pages 85-99.

- ^ Donald, pg. 38. In speaking of an incident when Lincoln openly referred to the four years he "slept with Joshua", Donald wrote, "I simply cannot believe that, if the early relationship between Joshua Speed and Lincoln had been sexual, the President of the United States would so freely and publicly speak of it."

- ^ Donald, pg. 36. Donald states, "Though nearly every other possible charge against Lincoln was raised during his long public career – from his alleged illegitimacy to his possible romance with Ann Rutledge, to the breakup of his engagement to Mary Todd, to some turbulent aspects of their marriage – no one ever suggested that he and Speed were sexual partners."

- ^ Vanity Fair Was Lincoln Bisexual BY GORE VIDAL, JANUARY 2005

- ^ Letter from Lincoln to Speed in August 1855.

- ^ Fried, Ronald K. (2016-05-15). "Debunking the Myth That Lincoln Was Gay". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2021-08-09.

- ^ Tripp, C.A. : Intimate World, Ibid.

- ^ Martin P. Johnson, "Did Abraham Lincoln Sleep with His Bodyguard? Another Look at the Evidence" Archived 2007-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Vol 27 No 2 (Summer 2006)

- ^ D. H. Donald, We are Lincoln Men, pp. 141-143 Simon & Schuster, 2003, ISBN 0-7432-5468-6

Further reading

[edit]- Hay, John; Nicolay, John George (1890). Abraham Lincoln: A History. Ten volumes.

- Michael F. Bishop, "All the President's Men", The Washington Post, February 13, 2005; Page BW03 online Review of Tripp, C. A., The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln.

- Book Questions Abraham Lincoln's Sexuality - Discovery Channel

- "The sexual life of Abraham Lincoln" by Andrew O'Hehir, Salon.com, Jan. 12, 2005.

- The Lincoln Bedroom: A Critical Symposium Claremont Review of Books, Summer 2005

- Exploring Lincoln's Loves Scott Simon in conversation with Lincoln scholars Michael Chesson and Michael Burlingame. National Public Radio, February 12, 2005

- We Are Lincoln Men Margaret Warner speaks with Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Herbert Donald about his book, We Are Lincoln Men: Abraham Lincoln and His Friends. Public Broadcasting Service, November 26, 2003

- Jay Hatheway. American Historical Review 111#2 (April 2006) - An Edgewood College history professor's book review of C.A. Tripp's The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln online

- Mr. Lincoln and Friends: Joshua F. Speed Archived 2016-03-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Strozier, Charles B. (2016). Your Friend Forever, A. Lincoln: The Enduring Friendship of Abraham Lincoln and Joshua Speed. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54130-5.

New research reveals a more emotional and troubled President Abraham Lincoln at Wikinews

New research reveals a more emotional and troubled President Abraham Lincoln at Wikinews