Daily life of the Etruscans

Daily life among the Etruscans is difficult to trace, as few literary testimonies are available and Etruscan historiography was highly controversial in the 19th century (see Etruscology).

Most of our knowledge of the habits and customs of Etruscan daily life is available through detailed observation of the funerary furnishings in their family tombs: decorated urns and sarcophagi, accompanied by everyday objects for both men and women, details of frescoes and bas-reliefs, most of which were discovered in the 18th and 19th centuries, when the scientific study of their civilization really began.

The table

[edit]

Nevertheless, a Greek historian, Posidonios, described the richness of the Etruscan table: "Twice a day, the Etruscans prepared a sumptuous table with all the amenities of a fine life; arranged tablecloths embroidered with flowers; covered the table with a large quantity of silver crockery; had a considerable number of slaves serve them".[note 1] This points to the life of wealthy men, quite different from that of the common people.

The abundant forests of the Etruscan territory enabled the construction of a maritime fleet, as well as mineral exploitation. The prosperity of its trade was based on the export of crafts (bucchero), large quantities of wine and the import of tin from Gaul. From at least the 6th century BC,[1] vine cultivation and wine production have been documented in the region, as evidenced by the manufacture of amphorae for transporting wine, which were widely distributed in the Tyrrhenian and Mediterranean seas.

Etruscan's diet

[edit]

The Etruscans' basic diet[2] consisted mainly of cereal porridge and vegetables. Salt and freshwater fish were certainly part of the diet. Meat consumption was linked to ritual sacrifices and eaten on religious feast days. The hare, depicted on vases in hunting scenes, was a highly prized game animal. Many kitchen utensils, colanders, amphorae, vases, bronze ladles and typical fish plates are on display in European museums, including the Altes Museum, the Louvre and the National Etruscan Museum at Villa Giulia.

Testaroli is an ancient pasta that originated from the Etruscan civilization. The book Rustico: Regional Italian Country Cooking states that testaroli is "a direct descendant of the porridges of the Neolithic age that were poured over hot stones to cook". According to an article published by The Wall Street Journal, it is "the earliest recorded pasta".

The pomp of a banquet

[edit]

The frescoes found in many Etruscan necropolis depict the Etruscans in the splendor of the Triclinium banquet, drinking and eating with opulence (also evident in the lids of the figurative sarcophagi). The frescoes show the richness of the crockery and everyday objects (such as dices) found in the tombs, accompanying the deceased into the afterlife with the memory of their earthly life.[citation needed]

The games

[edit]Etruscan games, also depicted in tomb frescoes, were an important part of their lives. Herodotus recounts their many games: dice, kottabos, ball (episkyros or harpastum), Phersu, Askôliasmos, and borsa.

The Etruscans drew direct inspiration from Greek practices for their pan-Etruscan sports games (Volsinies), pugilism and wrestling, throwing the discus, javelin, long jump, simple foot race or running with weapons (hoplitodromia). Some ludi circenses (games), which later the Romans partly took up, were different, such as mounted horse racing (bas-reliefs in Poggio Civitate), acrobatics by desultores, chariot racing (biga, triga and quadriga), which the auriga (slaves) practised with the reins tied behind their backs.

The Romans also took up other games known as ludi scaenici, ritual and votive stage games,[3] dance or ballet performances (including the histrionics),[4] which Varro tells us[5] were performed by an Etruscan tragedy writer called Volnius, for a genuinely theatrical purpose.

The music

[edit]The frescoes depict dancers, and musicians playing various instruments. This practice is also present on the many Hellenistic-inspired vases.

Festivities and rituals accompanied urban and agricultural life, and music was as much a part of this as the dancing it provoked.[citation needed]

Social rituals

[edit]

Etruscan divination was used to guide decision-making, and the remains of various buildings reveal the practice (the templum for the Etruscan temple) or the superstitions and beliefs that accompanied it (acroterial statues such as the "cowboy of Murlo").

Etruscan mythology, adapted from that of the Greeks, accompanied every gesture of daily life, including the home (Lares and Penates gods), farming, warfare and town-building (protective genius).

Family

[edit]- Passing on the father's and mother's surnames to children.

- Equal rights and powers for men and women

Clothing

[edit]- Bell skirt (Tomb of Francesca Giustiniani - Monterozzi)

- Dancers' costumes and shoes with colts (Tomb of the Triclinium, Tomb of the Leopards - Tarquinia)

Shoes

[edit]- Sandals (Tyrrhenica sandalia) widespread as far away as Athens (Cratinos, 5th century BC) with wooden soles held together by metal frames (Bisenzio, Caere)[6]

- Calcei repandi, shoes with a sheath (Tomb of the Augurs, Tomb of the Baron - Monterozzi, Sarcophagus of the Spouses of Caere)

- Brodequins worn by the Arringatore, Velia Seitithi and her slave (Tomb of the Shields - Monterozzi) with straps ("Tyrrhenian", the Tyrrhena pedum according to Virgil)

Hats

[edit]- The tutulus, a conical feminine bonnet (Tomb of the Lionesses of Monterozzi, Sarcophagus of the Spouses of Caere, spectators from the Tomb of the Biges of Tarquinia)

Horse equipment

[edit]- Phalera (military decoration)

Social structure

[edit]- The founding ritual of a city

- Roads between cities

- The citizens

- The aristocracy of princes

- The gentilices

- Freed servants (oiketes)

- Slaves (servus)

- Serfs (penestes)

- Independent peasants

- Artisans who held important positions[note 2]

- The division of time and the Etruscan calendar:

- the day from noon to noon (as opposed to midnight to midnight for the Babylonians and Romans, and sunset to sunset for the Greeks)[7]

- the weeks, the nones of eight full days (nundinae) and market day on the ninth

- the months, based on the lunar cycle, with the full moon in the middle, the Ides (which the Romans took over)

- the elapsed years are indicated by a nail driven into the wall of the temple of the goddess Nortia (taken over by the Romans in the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus)

- the centuries of varying length (up to 119 and 123 years, exceeding the maximum human lifespan), each passage of which is subject to prodigies (the Etruscan nation was expected to last ten centuries) (Censor).

- The villa and its well-attributed features:

- the atrium with its compluvium and impluvium

- the tablinum

Some objects

[edit]- The simple plough

- The comb

- Hand fans with ivory hand shaped handles (Vulci)[8]

- Cauldron or basin and tripod (Tarquinia)

- Cheese graters (Chianciano Terme and Sarteano)

- The Graffione, the roasting spit (Chianciano Terme and Piombino)

- The colander handle[9]

- The half-moon razor

- The censer, a theriomorphic cult chariot[9] (a zoomorphic figure with a mixture of bird bodies and deer heads, all mounted on wheels, on display at Tarquinia)[8]

- The perfume needle (Poggio Civitate)

- The double-bulb vase

- Vase with the full alphabet written around the rim (probably used as an inkwell)

- The two-wheeled cart with tarpaulin under hoops

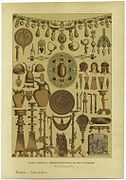

Some objects were originally from the area, while others were imported and then modified locally by adding figures (recognisable because they were more rudimentary). [10]

-

Plate of various objects presumed to be Etruscan, in gold and bronze.

-

Relief details of everyday objects on the walls and columns of the Tomb of the Reliefs.

-

Etruscan razor

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Filipo Delfino, translated from italian by Émilie Formoso, « La culture de la vigne et la consommation de vin » in Les Dossiers d'archéologie n°322 July-August 2007, p. 81

- ^ Mireille Cebeillac-Gervasoni, « L'alimentation chez les Étrusques » in Archeologia, No. 238, 1988, p. 21

- ^ Livy, VII, 2

- ^ Dominique Briquel, La Civilisation étrusque, p. 177-179.

- ^ Varron, Treaty on the Latin language, V, 55

- ^ Jacques Heurgon, La Vie quotidienne des Étrusques, Hachette, 1961 and 1989, p. 223

- ^ Jacques Heurgon, La Vie quotidienne des Étrusques, Hachette, 1961 and 1989, p. 229

- ^ a b Jean-Paul Thuillier, Les Étrusques, la fin d'un mystère, p. 56

- ^ a b p. 279 in Les Étrusques et l'Europe, prefaced by Massimo Pallottino, following the eponymous exhibition at the "Grand-Palais", Paris, between 15 September and 14 December 1992, and in Berlin in 1993

- ^ Note by R.Bianchi Bandinelli in Jean-Paul Thuillier, Les Étrusques, la fin d'un mystère, p. 56

Bibliography

[edit]- Briquel, Dominique (1993). Les Étrusques. Peuple de la différence. Armand Colin.

- Briquel, Dominique (1999). La Civilisation étrusque. Fayard. p. 353. ISBN 2-213-60385-5.

- Briquel, Dominique (2012). Les Étrusques (2nd ed.).

- Jannot, Jean-René (1987). À la rencontre des Étrusques. Ouest France.

- Heurgon, Jacques (1961). La Vie quotidienne des Étrusques. Hachette.

- Hus, Alain (1971). Vulci étrusque et étrusco-romaine (Klincksieck ed.). p. 228.

- Hus, Alain (1980). Les Étrusques et leur destin. Picard.

- Irollo, Jean-Marc (2010). Histoire des Étrusques. Tempus.

- Rossi, Fulvia; Locatelli, Davide (2010). Les Étrusques: pouvoir, religion, vie quotidienne. Hazan.

- Thuillier, Jean-Paul (1990). Les Étrusques: La fin d'un mystère. Gallimard. ISBN 2-07-053026-4.

- Thuillier, Jean-Paul (2003). Les Étrusques. Histoire d'un peuple. Armand Colin.