Crossrail

| Crossrail | |

|---|---|

| |

Crossrail platform at Farringdon | |

| Overview | |

| Other name(s) | Elizabeth line |

| Owner | Transport for London |

| Locale | |

| Termini |

|

| Stations | 10 |

| Website | www |

| Service | |

| Type | |

| System | National Rail |

| Rolling stock | Class 345 (9 carriages per train) |

| History | |

| Opened | 24 May 2022 Paddington–Abbey Wood |

| Technical | |

| Number of tracks | 2 |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Electrification | 25 kV 50 Hz AC (overhead lines) |

| Operating speed | 60 mph (95 km/h) |

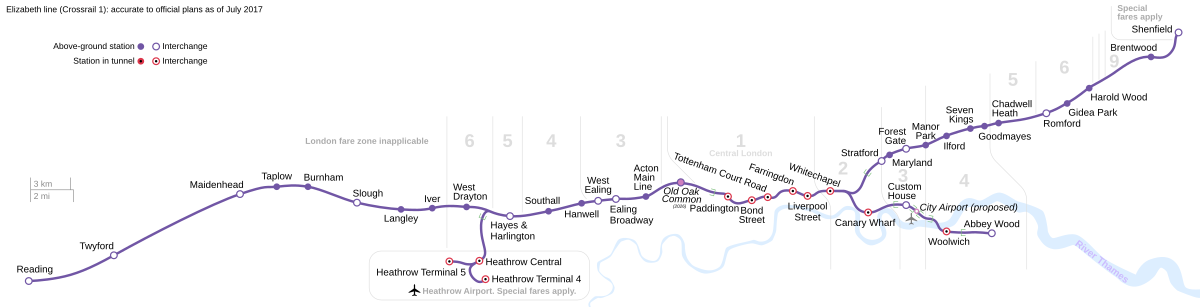

Crossrail is a completed railway project centred on London. It provides a high-frequency hybrid commuter rail and rapid transit system, known as the Elizabeth line, that crosses the capital from suburbs on the west to east and connects two major railway lines terminating in London: the Great Western Main Line and the Great Eastern Main Line. The project was approved in 2007, and construction began in 2009 on the central section and connections to existing lines that became part of the route, which has been named the Elizabeth line in honour of Queen Elizabeth II who opened the line on 17 May 2022 during her Platinum Jubilee. The central section of the line between Paddington and Abbey Wood opened on 24 May 2022, with 12 trains per hour running in each direction through the core section in Central London.

The main feature of the project was the construction of a new railway line that runs underground from Paddington Station to a junction near Whitechapel. There it splits into a branch to Stratford, where it joins the Great Eastern Main Line; and a branch to Abbey Wood in southeast London.

When the Elizabeth line became fully operational in May 2023, the new nine-carriage Class 345 trains started to run at frequencies in the central section of up to 24 trains per hour in each direction through the central core, after which services divide into two branches: in the west to Reading and to Heathrow Central; in the east to Abbey Wood and to Shenfield. Local services on the section of the Great Eastern Main Line between Liverpool Street and Shenfield had been transferred to TfL Rail in May 2015; TfL Rail also took over Heathrow Connect services in May 2018 and replaced some local services between Paddington and Reading in December 2019. The TfL Rail brand was discontinued when the core section of the Elizabeth line opened in May 2022.

The Elizabeth line is operated by MTR Corporation (Crossrail) Ltd as a London Rail concession of Transport for London (TfL), in a similar manner to London Overground. TfL's annual revenues from the line were forecast in 2018 to be nearly £500 million in 2022–23 and over £1 billion from 2024 to 2025.

The total estimated cost rose from an initial budget of £14.8 billion to £18.8 billion by December 2020. Originally planned to open in 2018, the project was repeatedly delayed, including several months caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

History

[edit]| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1941–48 | Proposals for cross-London railway tunnel(s), of the national network, by George Dow |

| 1974 | London Rail Study Report recommends a Paddington–Liverpool Street "Crossrail" tunnel |

| 1989 | Central London Rail Study proposes three Crossrail schemes, including an east–west Paddington or Marylebone–Liverpool Street route |

| 1991 | Private bill promoted by London Underground and British Rail submitted to Parliament proposing a Paddington–Liverpool Street tunnel; it was rejected in 1994 |

| 2001 | Crossrail scheme promoted through Cross London Rail Links (CLRL) |

| 2004 | Senior railway managers promote an expanded regional Superlink scheme |

| 2005 | Crossrail Bill put before Parliament |

| 2008 | Crossrail Act 2008 receives royal assent |

| 2009 | Construction work begins at Canary Wharf |

| 2015 | Liverpool Street–Shenfield service transferred to TfL Rail |

| 2017 | New Crossrail trains introduced on Liverpool Street–Shenfield route |

| 2018 | Paddington–Heathrow services transferred to TfL Rail |

| 2019 | TfL Rail begin operating Paddington–Reading services |

| 24 May 2022 | Paddington–Abbey Wood services begin |

| 6 November 2022 | Reading and Heathrow–Abbey Wood, and Paddington–Shenfield services begin |

| 21 May 2023[2] | full route opening for passenger trains |

Early proposals

[edit]The concept of large-diameter tunnels crossing central London to connect Paddington in the west and Liverpool Street in the east was first proposed by railwayman George Dow in The Star newspaper in June 1941.[3] The project that became Crossrail has origins in the 1943 County of London Plan and 1944 Greater London Plan by Patrick Abercrombie. These led to a specialist investigation by the Railway (London Plan) Committee, appointed in 1944 and reporting in 1946 and 1948.[4]

The term "Crossrail" emerged in the 1974 London Rail Study Report.[5] Although the idea was seen as imaginative, only a brief estimate of cost was given: £300 million. A feasibility study was recommended as a high priority so that the practicability and costs of the scheme could be determined. It was also suggested that the alignment of the tunnels should be safeguarded[6][7] while a final decision was taken.

Later proposals

[edit]The Central London Rail Study of 1989 proposed tunnels linking the existing rail network as the "East–West Crossrail", "City Crossrail", and "North–South Crossrail" schemes. The east–west scheme was for a line from Liverpool Street to Paddington/Marylebone with two connections at its western end linking the tunnel to the Great Western Main Line and the Metropolitan line on the Underground. The City route was shown as a new connection across the City of London linking the Great Northern Route with London Bridge.

The north–south line proposed routing West Coast Main Line, Thameslink, and Great Northern trains through Euston and King's Cross/St Pancras, then under the West End via Tottenham Court Road, Piccadilly Circus and Victoria towards Crystal Palace and Hounslow. The report also recommended a number of other schemes including a "Thameslink Metro" route enhancement, and the Chelsea–Hackney line. The cost of the east–west scheme including rolling stock was estimated at £885 million.[8]

In 1991, a private bill was submitted to Parliament for a scheme including a new underground line from Paddington to Liverpool Street.[9] The bill was promoted by London Underground and British Rail, and supported by the government; it was rejected by the Private Bill Committee in 1994[10] on the grounds that a case had not been made, though the government issued "Safeguarding Directions", protecting the route from any development that would jeopardise future schemes.[11]

In 2001, Cross London Rail Links (CLRL), a joint-venture between TfL and the Department for Transport (DfT), was formed to develop and promote the Crossrail scheme,[12] and also a Wimbledon–Hackney scheme.

While CLRL was promoting the Crossrail project, alternative schemes were being proposed. In 2002, GB Railways put forward a scheme called SuperCrossRail which would link regional stations such as Cambridge, Guildford, Oxford, Milton Keynes Central, Southend Victoria and Ipswich via a west–east rail tunnel through central London. The tunnel would follow an alignment along the River Thames, with stations at Charing Cross, Blackfriars and London Bridge. In 2004 another proposal named Superlink was promoted by a group of senior railway managers. Like SuperCrossRail, Superlink envisaged linking a number of regional stations via a tunnel through London, but advocated the route already safeguarded for Crossrail. CLRL evaluated both proposals and rejected them due to concerns about network capacity and cost issues.[13][14]

Approval

[edit]The Crossrail Act 2008 was given royal assent in July 2008,[15][16] giving CLRL the powers necessary to build the line.[17] In September 2009, TfL was loaned £1 billion towards the project by the European Investment Bank.[18] Both Conservatives and Labour made commitments in their 2010 election manifestos to deliver Crossrail, and the coalition government following the election was committed to the project.[19]

Construction

[edit]

Chronology

[edit]

In April 2009, Crossrail announced that 17 firms had secured 'Enabling Works Framework Agreements' and would now be able to compete for packages of works.[20] At the peak of construction up to 14,000 people were expected to be needed in the project's supply chain.[21][22]

Work began on 15 May 2009 when piling works started at the future Canary Wharf station.[23]

The threat of diseases being released by work on the project was raised by Lord James of Blackheath at the passing of the Crossrail Bill. He told the House of Lords select committee that 682 victims of anthrax had been brought into Smithfield in Farringdon with some contaminated meat in 1520 and then buried in the area.[24] On 24 June 2009 it was reported that no traces of anthrax or bubonic plague had been found on human bone fragments discovered during tunnelling.[25]

Invitations to tender for the two principal tunnelling contracts were published in the Official Journal of the European Union in August 2009. 'Tunnels West' (C300) was for twin 6.2-kilometre-long (3.9-mile) tunnels from Royal Oak through to the new Crossrail Farringdon Station, with a portal west of Paddington. The 'Tunnels East' (C305) request was for three tunnel sections and 'launch chambers' in east London.[26] Contracts were awarded in late 2010: the 'Tunnels West' contract was awarded to BAM Nuttall, Ferrovial Agroman and Kier Construction (BFK); the 'Tunnels East' contract was awarded to Dragados and John Sisk & Son.[27][28] The remaining tunnelling contract (C310, Plumstead to North Woolwich), which included a tunnel under the Thames, was awarded to Hochtief and J. Murphy & Sons in 2011.[29]

By September 2009, preparatory work for the £1 billion developments at Tottenham Court Road station had begun, with buildings (including the Astoria Theatre) being compulsorily purchased and demolished.[30]

In March 2010, contracts were awarded to civil engineering companies for the second round of 'enabling work' including 'Royal Oak Portal Taxi Facility Demolition', 'Demolition works for Crossrail Bond Street Station', 'Demolition works for Crossrail Tottenham Court Road Station' and 'Pudding Mill Lane Portal'.[31] In December 2010, contracts were awarded for most of the tunnelling work.[32] To assist with the skills required for the Crossrail project, Crossrail opened in 2011 the Tunnelling and Underground Construction Academy in Ilford.[33] The academy was handed over to TfL in 2017, who have sub-contracted its management to PROCAT.[34]

In February 2010, Crossrail was accused of bullying residents whose property lay on the route into selling for less than the market value.[35] A subsequent London Assembly report was highly critical of the insensitive way in which Crossrail had dealt with compulsory purchases and the lack of assistance given to the people and businesses affected.[36] There were also complaints from music fans, as the London Astoria was forced to close.[37]

In December 2011, a contract to ship the excavated material from the tunnel to Wallasea Island[38] was awarded to a joint venture comprising BAM Nuttall Limited and Van Oord UK Limited.[39][40] Between 4.5 and 5 million tonnes of soil would be used to construct a new wetland nature reserve (Wallasea Wetlands).[38][41] The project eventually moved seven million tons of earth.[42]

Restoration of Connaught Tunnel by filling with concrete foam and reboring, as originally intended, was deemed too great a risk to the structural integrity of the tunnel, and so the docks above were drained to give access to the tunnel roof in order to enlarge its profile. This work took place during 2013.[43][44][45]

Boring of the railway tunnels was officially completed at Farringdon on 4 June 2015 in the presence of the Prime Minister and the Mayor of London.[46]

Installation of the track was completed in September 2017.[47] The ETCS signalling was scheduled to be tested in the Heathrow tunnels over the winter of 2017–2018.[48] The south east section of the infrastructure was energised in February 2018, with the first test train run between Plumstead and Abbey Wood that month.[49] In May 2018 the overhead lines were powered up between Westbourne Park and Stepney, the installation of platform doors was completed,[50] and video was released of the first trains travelling through the tunnels.[51]

TfL Rail took over Heathrow Connect services from Paddington to Heathrow in May 2018.[52][48]

At the end of August 2018, four months before the scheduled opening of the core section of the line, it was announced that completion was delayed and that the line would not open before autumn 2019.[53]

In April 2019, it was announced that Crossrail would be completed between October 2020 and March 2021, two years behind schedule, and that it would not include the opening of the Bond Street station, one of ten new stations on the line.[54][55] The London Assembly's transport committee concluded that TfL played down the prospect of delays to the project in updates to Mayor of London Sadiq Khan, and called for TfL commissioner Mike Brown to consider his position.[56] Crossrail said major challenges before completion included writing and testing the software that would integrate the train with three different track signalling systems, and installing equipment inside the tunnels.[54]

In July 2019, it was announced that the line would not open in 2021, with TfL not expecting the full line from Heathrow to Shenfield to open until the early part of the 2023/24 financial year.[57]

In August 2020, Crossrail announced that the central section would be ready to open "in the first half of 2022".[58]

In May 2021, trial running commenced,[59] with the core section opened by Queen Elizabeth II for passenger service on 24 May 2022.[60]

Tunnel boring machines

[edit]

The project used eight 7.1-metre (23-foot) diameter tunnel-boring machines (TBM) from Herrenknecht AG (Germany). Two types are used; 'slurry' type for the Thames tunnel, which involves tunnelling through chalk; and 'Earth Pressure Balance Machines' (EPBM) for tunnelling through clay, sand and gravel (at lower levels through Lambeth Group and Thanet Sands ground formation). The TBMs weigh nearly 1,000 tonnes and are over 100 metres (330 feet) long.[61][62] The main tunnelling contracts were valued at around £1.5 billion.[63]

Crossrail ran a competition in January 2012 to name the TBMs, in which over 2,500 entries were received and 10 pairs of names short-listed. After a public vote in February 2012, the first three pairs of names were announced on 13 March and the last pair on 16 August 2013:[64][65]

- Ada and Phyllis, Royal Oak to Farringdon section, named after Ada Lovelace and Phyllis Pearsall

- Victoria and Elizabeth, Limmo Peninsula to Farringdon section, named after Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth II

- Mary and Sophia, Plumstead to North Woolwich section, named after Mary and Sophia, the wives respectively of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and his father Marc Isambard Brunel, builders of the first tunnel under the Thames

- Jessica and Ellie, Pudding Mill Lane to Stepney Green and Limmo Peninsula to Victoria Dock sections, named after Jessica Ennis and Ellie Simmonds

Health, safety, and industrial relations

[edit]

In September 2012, a gantry supporting a spoil hopper, used to load rail wagons with excavated waste at a construction site near Westbourne Park Underground station, collapsed. It tipped sideways, causing the adjacent Network Rail line to be closed.[66][67]

On 7 March 2014, Rene Tkacik, a Slovakian construction worker, was killed by a piece of falling concrete while working in a tunnel.[68] In April 2014, The Observer reported details of a leaked internal report, compiled for the Crossrail contractors by an independent safety consultancy. The report was alleged to have pointed to poor industrial relations arising from safety concerns, and that workers were "too scared to report injuries for fear of being sacked".[69]

Three construction workers died from suspected heart attacks over six months in 2019, but Crossrail announced that, following extensive testing, the air quality at Bond Street station was within acceptable limits.[70]

Blacklisting

[edit]In 2012, Crossrail faced accusations of blacklisting. It was revealed that an industrial relations manager, Ron Barron, employed by Bechtel, had routinely cross-checked job applicants against the Consulting Association database.[71] An employment tribunal in 2010 heard that Barron introduced the use of the blacklist at his former employer, the construction firm Chicago Bridge & Iron Company (CB&I), and referred to it more than 900 times in 2007 alone. He was found to have unlawfully refused employment to a Philip Willis. Aggravated damages were awarded because Barron had added information about Willis to the blacklist.[71]

In May 2012, a BFK manager challenged their subcontractor, Electrical Installations Services Ltd. (EIS), saying that one of their electricians was a trade union activist. Some days later, Pat Swift, the HR manager for BFK and a regular user of the Consulting Association, again challenged EIS. EIS refused to dismiss their worker and lost the contract. Flash pickets were held at the Crossrail site and also at the sites of the BFK partners.[citation needed] The Scottish Affairs Select Committee called on the UK Business Secretary, Vince Cable, to set up a government investigation into blacklisting at Crossrail.[72][73]

Further allegations of blacklisting against Crossrail were made in Parliament in September 2017.[74]

In March 2023, a former Crossrail worker made a High Court statement regarding a damages claim against Crossrail, Skanska, Costain, T Clarke and NG Bailey for blacklisting. The case had been settled out of court in December 2021. Electrician Daniel Collins had raised health and safety concerns at the Bond Street station site in February 2015, was fired three days later, and faced repeated difficulties in gaining new employment on the project. He alleged there was a "secretive system of misuse of private information" about union activists. Crossrail and the contractors denied all Collins' allegations, saying they settled the court case "for purely commercial reasons" and "without admission of liability or wrongdoing". Collins received an undisclosed sum for damages and to cover court costs.[75]

Archaeology

[edit]Much like the Thames Tideway Scheme and the High Speed 2 projects, which were under development in London at the same time as Crossrail, the excavation works that took place during the project gave archaeologists a valuable opportunity to explore the earth underneath London's streets that was previously seen as inaccessible. Crossrail undertook what was described as one of the most extensive archaeological programmes ever seen in the UK. Over 100 archaeologists have found tens of thousands of items from 40 sites, spanning 55 million years of London's history and prehistory.[76] Many of the items were placed on show at the Museum of London Docklands from February to September 2017. Some of the most notable finds include:[77][78]

- Victims of the Great Plague, a mass grave of 42 skeletons found at Liverpool Street station

- Thirteen skeletons, thought to be of victims of the Black Death in the 14th century, uncovered 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) under the road that surrounds the gardens in Charterhouse Square, Farringdon in March 2013[79][80]

- Prehistoric knapped flints discovered in North Woolwich

- A Tudor period bowling ball found in Stepney Green

- Medieval ice skates found near Liverpool Street station

- Bison and reindeer bones

- Leather shoes dating from the Tudor period

- Roman coins and a Roman medallion found at Liverpool Street which was issued to mark the New Year celebrations in AD 245. This medallion was only the second ever of its kind to be found in Europe.

- Two parts of a woolly mammoth jawbone

- The largest piece of amber ever found in the UK, discovered at Canary Wharf

- A Victorian chamber pot found near Stepney Green

- 13,000 Crosse & Blackwell jars found near Tottenham Court Road from the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[81]

- Part of a small barge or fishing vessel from 1223 to 1290 found at Canning Town

Operational testing

[edit]In the first half of 2021, Crossrail entered trial running stage of construction.[82] Crossrail, in partnership with TfL, ran trains to a timetable through the core section, to check the reliability of the railway. In November 2021, Crossrail entered trial operation which is the final stage before opening.[83]

Expected completion

[edit]With an initial budget of £14.8 billion, the total cost rose to £18.25 billion by November 2019,[84][85] and increased further to £18.8 billion by December 2020.[86] Delays to the project of several months were caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in England,[87][88] and in late 2020 this reduced the number of workers that could be safely on-site.[89]

By August 2021, seven of the nine new stations had been handed over to TfL.[90]

The Abbey Wood to Paddington section opened to passengers on 24 May 2022, although initially trains did not run on Sundays to allow for further testing, nor did they call at Bond Street, which opened on 24 October 2022. From Sunday 6 November trains began running directly from Reading and Heathrow in the west to Abbey Wood, and from Shenfield in the east through to Paddington as the surface railways connect with the central tunnels.[91] TfL expects that the full line, with final timetable, will be operational by May 2023.[92]

Route

[edit]

In the west, the new tunnel connects with the Great Western Main Line at Royal Oak, west of Paddington. East of Whitechapel the line splits at an underground junction. The north-eastern branch emerges to join the existing Great Eastern Main Line at Stratford. The south-eastern branch runs underground to Abbey Wood via Canary Wharf, Custom House and Woolwich. This branch takes over a stretch of the former North London line built by the Eastern Counties and Thames Junction Railway, and connects it with the North Kent Line via a tunnel under the Thames at North Woolwich.[93]

The tunnelled sections are altogether approximately 42 km (26 miles) in length.[94]

There are new stations at Paddington, Bond Street, Tottenham Court Road, Farringdon, Liverpool Street and Whitechapel, with interchanges with London Underground and National Rail services. Due to the length and positioning of the new platforms, Farringdon station is also connected to Barbican station,[95] and Liverpool Street to Moorgate station.[96]

Western end

[edit]From the western end of the tunnel Elizabeth line services continue to Hayes and Harlington where they either remain on the Great Western Main Line and run to Reading or Maidenhead via Slough or split off to the Heathrow branch terminating at Heathrow Terminals 4 or 5. Existing stations were refurbished and upgraded, including the provision of step-free access at all stations, and platform lengthening at most to accommodate the new 200-metre-long (660 ft) trains.[97]

Earlier plans suggested terminating at Maidenhead, with an extension to Reading safeguarded.[98] Various commentators advocated an extension further west as far as Reading because it was seen as complementary to the Great Western Electrification project which was announced in July 2009.[99] A Reading terminus was also recommended by Network Rail's 2011 Route Utilisation Strategy.[100] On 27 March 2014 it was announced that the line would indeed extend to Reading.[101][102][103]

A flyover at Airport Junction near Hayes & Harlington station allows Heathrow Express trains to pass over the track used by Crossrail, avoiding delays caused by crossings.[104] The line between the junction and Heathrow Central (mostly in a tunnel) is not owned by Network Rail but by Heathrow Airport Holdings.

A "dive-under" was constructed at Acton to allow passenger trains to pass slower freight trains leaving and entering a goods yard. It was completed in July 2016 and was brought into use in 2017.[105][106]

Eastern end

[edit]The north-eastern Crossrail tunnel connects with the Great Eastern Main Line at Stratford. The Elizabeth line runs to Shenfield via Ilford, Romford and Gidea Park.[107]

Design and infrastructure

[edit]

Name and identity

[edit]Crossrail is the name of the construction project and of the limited company, wholly owned by TfL, that was formed to carry out construction works.[108][109] The Elizabeth line is the name of the new service that will be seen on signage throughout the stations. It is named in honour of Queen Elizabeth II.[110][111] The Elizabeth line logo features a Transport for London roundel with a purple ring and TfL-blue bar with white text. TfL Rail was an intermediate brand name which was introduced in May 2015 and discontinued in May 2022. It was used by TfL on services between Paddington and Heathrow Terminal 5 and Reading, as well as trains between Liverpool Street and Shenfield.[112]

Tunnels

[edit]21 km (13 miles) of twin-bore tunnels were constructed by tunnel boring machines (TBM), each with an internal diameter of 6.2 m (20 ft 4 in)[61] (compared with 3.81 m (12 ft 6 in) for the deep-level Victoria line). The wide-diameter tunnels allow for new Class 345 rolling stock, which is larger than the traditional deep-level tube trains. The tunnels allow for the emergency evacuation of passengers through the side doors rather than along the length of the train.

The tunnels are made up of three main sections: a 15.39 km (9.6 miles) tunnel from Royal Oak portal near Royal Oak station to Victoria Dock portal near Custom House station, a 2.72 km (1.7 miles) tunnel from Pudding Mill Lane portal connecting to the longer tunnel at an underground junction at Stepney Green cavern, and a separate 2.64 km (1.6 miles) tunnel from Plumstead to North Woolwich underneath the Thames. The Custom House to North Woolwich section, included a £50 million investment to renovate and reuse the Connaught tunnel.[113][114]

Crossrail has often been compared to Paris's RER system due to the length of the central tunnel.[115][116]

Stations

[edit]

The majority of stations in the central section all have distinctive architecture at street level; whereas stations at platform level have identical "kit-of-parts" architecture, including full height platform screen doors with integrated passenger information displays.[93] This is a different approach from the Jubilee Line Extension in the 1990s, where each station was designed by a different architect.[117] Artwork was also installed at seven of the stations in the central section.[118]

A mock-up of the new stations was built in Bedfordshire in 2011 to ensure that their architectural integrity would last for a century.[119] It was planned to bring at least one mock-up to London for the public to view the design and give feedback before final construction commenced.[120]

81 escalators were installed at the nine new stations.[121] At 60 metres (200 ft) in length, the escalators at Bond Street are just one metre shorter than the escalators at Angel, the longest escalator on the Underground.[121] All stations in the central section were built to be step free from street to train, with 54 lifts installed in the nine new stations.[122][121]

Existing stations on the Great Western Main Line and Great Eastern Main Line were upgraded and refurbished, with some stations receiving new entrance buildings.[123] All surface level stations have lifts, allowing step free access from street to platform.[124][123]

Elizabeth line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Electrification and signalling

[edit]Crossrail uses 25 kV, 50 Hz AC overhead lines, which are also used on the Great Eastern and Great Western Main Lines.

The Heathrow branch started using the European Train Control System (ETCS) in 2020. The Automatic Warning (AWS) and Train Protection & Warning (TPWS) systems are used on the Great Western and Great Eastern Main Lines, with possible later upgrades to ETCS. Communications-based train control (CBTC) is installed in the central section and the Abbey Wood branch.[126][127][128]

Depots

[edit]Crossrail will have depots in west London at Old Oak Common TMD, in south-east London at Plumstead Depot, and in east London at Ilford EMU Depot and at a new signalling centre at Romford in Havering, East London.[129][130]

Further proposals

[edit]Additional stations

[edit]

Silvertown (London City Airport)

[edit]Although the Crossrail route passes very close to London City Airport, there is no station serving the airport directly. London City Airport had proposed the re-opening of Silvertown railway station, in order to create an interchange between the rail line and the airport.[131] The self-funded £50 million station plan was supported 'in principle' by the London Borough of Newham.[132] Provisions for re-opening of the station were made in 2012 by Crossrail.[133] However, it was alleged by the airport that TfL was hostile to the idea of a station on the site, a claim disputed by TfL.[134]

In 2018, the airport's chief development officer described the lack of a Crossrail station as a "missed opportunity", but did not rule out a future station for the airport.[135] The CEO stated in an interview that a station is not essential to the airport's success.[136] In May 2019, the chief development officer confirmed discussions are ongoing about a station for the airport as part of the proposed extension to Ebbsfleet.[137]

Old Oak Common

[edit]As part of the High Speed 2 (HS2) rail link from London to Birmingham, a new station is being built at Old Oak Common between Paddington and Acton Main Line station.[138] The new station will connect HS2 services with Crossrail and National Rail services on the Great Western Main Line, as well as London Overground services running through the area.[139] The original plan was that the station would open with High Speed 2 in 2026, with preliminary construction beginning in 2019.[140] Go-ahead for construction was given in June 2021.[141][142]

Extensions

[edit]

To Ebbsfleet and Gravesend

[edit]In the 2003 and 2004 consultations into Crossrail, the South East branch was proposed to go beyond Abbey Wood, running along the North Kent Line to Ebbsfleet, linking up with the (then under construction) Channel Tunnel Rail Link.[144][145] However, prior to the submission of the Crossrail Hybrid Bill to Parliament in 2005, the branch was truncated at Abbey Wood to cut overall project costs.[146] Although dropped from the main scheme, the route was safeguarded by the DfT as far as Gravesend and Hoo Junction, protecting the route from development.[147]

With the Crossrail project nearing completion in 2018, local MPs, council leaders and local businesses began lobbying[148] the government to fund the development of a business case for the extension to Ebbsfleet,[149][150] with the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan including the project in his Mayor's Transport Strategy.[151] The Mayor's Transport Strategy estimated that an extension could assist in delivering 55,000 new homes and 50,000 new jobs planned along the route in Bexley and north Kent.[152] In March 2019, the Government committed £4.8 million on exploratory work into the extension as part of the Thames Estuary 2050 Growth Commission.[153][146]

The following stations are on the protected route extension to Gravesend: Belvedere, Erith, Slade Green, Dartford, Stone Crossing, Greenhithe for Bluewater, Swanscombe, Ebbsfleet, Northfleet, and Gravesend.[154]

To the West Coast Main Line

[edit]Network Rail's July 2011 London & South East Route Utilisation Strategy (RUS) recommended that a short railway line could be built to connect the West Coast Main Line (WCML) with the Crossrail route. This would enable train services that currently run between Milton Keynes Central and London Euston to be re-routed via Old Oak Common to serve central London, Shenfield and Abbey Wood. The report argued that this would free up capacity at Euston for the planned High Speed 2, reduce London Underground congestion at Euston, make better use of Crossrail's capacity west of Paddington, and improve access to Heathrow Airport from the north.[155] Under this scheme, all Crossrail trains would continue west of Paddington, instead of some of them terminating there. They would serve Heathrow Airport (10 tph), stations to Maidenhead and Reading (6 tph), and stations to Milton Keynes Central (8 tph).[156]

In August 2014, a statement by transport secretary Patrick McLoughlin indicated that the government was actively evaluating the extension of Crossrail as far as Tring and Milton Keynes Central, with potential Crossrail stops at Wembley Central, Harrow & Wealdstone, Bushey, Watford Junction, Kings Langley, Apsley, Hemel Hempstead, Berkhamsted, Tring, Cheddington, Leighton Buzzard and Bletchley. The extension would relieve some pressure from London Underground and London Euston station while also increasing connectivity. Conditions to the extension were that any extra services should not affect the planned service pattern for confirmed routes, as well as affordability.[157][158] This proposal was shelved in August 2016 due to "poor overall value for money to the taxpayer".[159]

To Staines

[edit]As part of the Heathrow Southern Railway scheme proposed in 2017, the western extent of the Crossrail route could be extended beyond Heathrow Airport to terminate at Staines. This extension would form part of a wider scheme to create new rail links in west London and Surrey serving Heathrow, and would require the construction of an extra platform at Staines station. This proposal has not been approved or funded.[160]

To Southend Airport

[edit]Stobart Aviation, the company that previously operated Southend Airport in Essex, proposed that Crossrail should be extended beyond Shenfield along the Shenfield–Southend line to serve Southend Airport and Southend Victoria. The company has suggested that a direct Heathrow-Southend link could alleviate capacity problems at Heathrow.[161] The extension proposal has been supported by Southend-on-Sea City Council.[162]

Management and franchise

[edit]Funding for the project came from:

- TfL

- Mayoral Community Infrastructure Levy (a local tax charged on property developments across Greater London, with different charging rates for each London borough)[163]

- Crossrail Business Rate Supplement (additional business rates)

- Section 106 Agreement payments

- Over-site development opportunities

- UK Government

- City of London Corporation

- Major landowners: Canary Wharf Group, Heathrow Airport Holdings, and Berkeley Homes.

Crossrail was built by Crossrail Ltd, jointly owned by TfL and the DfT until December 2008, when full ownership was transferred to TfL. In 2007, Crossrail had a £15.9 billion funding package in place[164] for the construction of the line. Although the branch lines to the west and to Shenfield will still be owned by Network Rail, the tunnel will be owned and operated by TfL.[165]

On 18 July 2014, TfL London Rail said that MTR Corp had won the concession to operate the services for eight years, with an option for two more years.[166] The concession will be similar to London Overground.[167][non-primary source needed] It is planned for the franchise to run for eight years from May 2015,[166] taking over control of Shenfield metro services from Abellio Greater Anglia in May 2015,[166] and Reading / Heathrow services from Great Western Railway in 2018.[168]

In anticipation of a May 2015 transfer of Shenfield to Liverpool Street services from the East Anglia franchise to Crossrail, the invitation to tender for the 2012–2013 franchise required the new rail operator to set up a separate "Crossrail business unit" for those services before the end of 2012, to allow transfer of services to the new Crossrail Train Operating Concession (CTOC) operator during the next franchise.[165][169]

The infrastructure of the core section is managed by Rail for London Infrastructure (RfLI), a subsidiary of TfL. Signalling is controlled by Network Rail's Romford Rail Operating Centre.[170]

See also

[edit]- Crossrail 2 – second proposed Crossrail route providing a new north–south rail link across Greater London.

- The Fifteen Billion Pound Railway – a documentary about the Elizabeth line's construction and commissioning

- Transport in London

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "TfL Rail: What we do". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ "The transformational Elizabeth line clocks more than one hundred million passenger journeys" (Press release). TfL. 1 February 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Dow, Andrew (2005). Telling the Passenger Where to Get Off. London: Capital Transport. pp. 52–55. ISBN 978-1-85414-291-7.

- ^ Jackson, Alan A.; Croome, Desmond F. (1962). Rails Through The Clay. London: Allen & Unwin. pp. 309–312. OCLC 55438.

- ^ London Rail Study Report Part 2, pub. GLC/DoE 1974, page 87–88

- ^ "Safeguarding". Crossrail. n.d. Archived from the original on 25 October 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ "London Rail Study". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 20 December 1974. col. 2111–2112. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

A further recommendation which concerns the Minister, this time wearing his planning hat, is that contained in paragraph 7.11. It concerns safeguarding the alignment for the Chelsea-Hackney line, Crossrail, and other schemes, from encroachment by other developments. Maps 6, 7 and 8 show the routes of the proposed lines. Will the Minister take the proposed routes into account when he considers planning applications for offices and other developments in London?

- ^ British Rail (Network SouthEast); London Regional Transport; London Underground (January 1989). "Central London Rail Study". Department of Transport. pp. 11–16, maps 3, 6 & 7.

- ^ "Crossrail Bill". 1991.

- ^ Norris, Steven (20 June 1994). "Crossrail". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

We were disappointed by the Private Bill Committee's decision not to find the preamble to the Crossrail Bill proved.

- ^ "Select Committee on the Crossrail Bill : 1st Special Report of Session 2007–08: Crossrail Bill" (PDF). House of Lords. Chapter 1: Introduction: The History of Crossrail, page 8.

- ^ "Sponsors and Partners". Crossrail. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

Crossrail Limited is the company charged with delivering Crossrail. Formerly known as Cross London Rail Links (CLRL), it was created in 2001 [..] Established as a 50/50 joint venture company between Transport for London and the Department for Transport, Crossrail Limited became a wholly owned subsidiary of TfL on 5 December 2008

- ^ "Rival cross-city rail plan aired". BBC News. 15 December 2004. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- ^ Landels, John (24 May 2005). "SuperCrossrail and Superlink Update Report" (PDF). Cross London Rail Links Limited. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ "Crossrail Bill 2005". Crossrail. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ "Soho shops make way for Crossrail". BBC News. 13 November 2009.

- ^ "Crossrail gets £230m BAA funding". BBC News. 4 November 2008. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ^ "Crossrail project gets £1bn loan". BBC News. 7 September 2009.

- ^ "New coalition government makes Crossrail pledge". BBC News. 15 April 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ^ Owen, Ed (9 April 2009). "Crossrail enabling works frameworks announced". New Civil Engineer. EMap. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ "Careers". Crossrail. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Crossrail pledges 14,000 jobs boom for Londoners". Evening Standard. London. 11 October 2007. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ Gerrard, Neil (15 May 2009). "Work officially starts on Crossrail". Contract Journal. Archived from the original on 17 May 2009.

- ^ "House of Lords – Crossrail Bill Examination of Witnesses (Questions 12705–12719)". UK Parliament. 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ "No anthrax in Crossrail remains". BBC News. 24 June 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ "Crossrail tunnelling contracts advertised" (Press release). Crossrail. 25 August 2009. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Crossrail awards major tunnelling contracts worth £1.25bn" (Press release). Crossrail. 10 December 2010. Archived from the original on 27 February 2011.

- ^ "Crossrail tunnel factory in Kent at full production". BBC News. 16 April 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ "Hochtief and Vinci win last Crossrail tunnels". The Construction Index. 4 August 2011.

- ^ "Crossrail station profile: Tottenham Court Road". New Civil Engineer. 24 September 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ "Crossrail to awards second round of enabling contracts". New Civil Engineer. 16 March 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ^ "Crossrail awards tunnelling contracts". Railway Gazette International. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 13 December 2010. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- ^ "TfL takes on TUCA – Tunnelsonline.info p.23 March 2017". Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ "Tunnelling academy's future secured – The Construction Index p.14 March 2017". Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Bar-Hillel, Mira (10 February 2010). "Boris Johnson takes on the 'bullies' evicting residents to make way for Crossrail". Evening Standard. London. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ "Light at the end of the tunnel". London Assembly. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- ^ Hoyle, Ben (14 March 2008). "Astoria makes way for Crossrail". The Times. London. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ^ a b Carrington, Damian (17 September 2012). "Crossrail earth to help create biggest man-made nature reserve in Europe". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "Crossrail awards contract to ship excavated material to Wallasea Island" (Press release). Crossrail. 16 December 2011. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012.

- ^ "Monster lift sends east London tunnelling machines 40 metres underground". Crossrail. 2013. Archived from the original on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ Morelle, Rebecca (17 September 2012). "Wallasea Island nature reserve project construction begins". BBC News. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "From railway to wildlife". The Telegraph. 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ "Crossrail team gain confidence". Modern Railways. July 2012. p. 37.

- ^ "Connaught Tunnel restoration complete" Archived 8 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Global Rail News, accessed 8 March 2014

- ^ "Breathing New Life into the Connaught Tunnel". Crossrail. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022.

- ^ MacLennan, Peter (4 June 2015). "Prime Minister and Mayor of London celebrate completion of Crossrail's tunnelling marathon" (Press release). Crossrail. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ "Elizabeth line permanent track installation is complete". Crossrail. 29 December 2022. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Elizabeth Line Operational Readiness and Integration" (PDF). Transport for London. 12 December 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ "First Elizabeth line train tests through Crossrail Tunnels". Construction Manager Magazine. 27 February 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ "Footage of train testing under London and new construction images highlight Elizabeth line progress". Crossrail. 29 December 2022. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018.

- ^ Neild, Barry (25 May 2018). "First look at epic new Crossrail tunnel ride under London". CNN. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ "TfL takes over Heathrow Connect services in Elizabeth line milestone". railtechnologymagazine.com. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Crossrail to miss December opening date". BBC News. 31 August 2018. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ a b "Crossrail to be finished 'by March 2021'". BBC News. 26 April 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Burroughs, David (26 April 2019). "Crossrail releases updated plan for delayed Elizabeth Line". International Railway Journal. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Weinfass, Ian (23 April 2019). "Crossrail delay: TfL boss 'should consider position'". Construction News. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Marshall2020-07-24T11:30:00+01:00, Jordan. "TfL planning for 2023 Crossrail opening". Building. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Crossrail needs extra £450m and delayed until 2022". BBC News. 21 August 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ "Trial Running Explained". Crossrail. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Sandle, Paul (24 May 2022). "London's $24 billion Crossrail finally opens". Reuters. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ a b Sources:

- "Crossrail Tunnel Boring Machines". Crossrail. 29 December 2022.

- "Crossrail information paper: D8 – Tunnel construction methodology" (PDF). Crossrail. 20 November 2007.[permanent dead link]

- Thomas, Tris (22 September 2011). "Herrenknecht supply final Crossrail TBMs". Tunneling Journal.

- ^ Sources:

- "Bulletin: The giant burrowers" (PDF). Crossrail Bulletin. No. 23. Crossrail. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2011.

- Symes, Claire (14 December 2011). "Crossrail's first TBM ready for delivery". New Civil Engineer.

- ^ "Crossrail awards remaining tunnelling contracts as Crossrail's momentum becomes unstoppable" (PDF) (Press release). Crossrail. 7 April 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2011.

- ^ "Names of our first six tunnel boring machines announced". Crossrail. 13 March 2012. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012.

- ^ "Olympic champions join Crossrail's marathon tunnelling race". Crossrail. 16 August 2013. Archived from the original on 11 September 2013.

- ^ Lewis, Mark (28 September 2012). "Gantry collapse at Westbourne Park Crossrail site". Construction News.

- ^ Freeman, Simon (28 September 2012). "Waste hopper collapses at Paddington station". Evening Standard. London.

- ^ "Slovakian identified as killed Crossrail worker". BBC News. 12 March 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ Boffey, Daniel (27 April 2014). "Crossrail managers accused of 'culture of spying and fear'". The Observer. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ Wadham, Caroline (15 October 2019). "Crossrail: Bond Street air quality 'within required limits'". Construction News.

- ^ a b Boffey, Daniel (2 December 2012). "Crossrail project dragged into blacklist scandal". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ Smith, Dave; Chamberlain, Phil (2015). Blacklisted The Secret War between Big Business and Union Activists. New Internationalist. ISBN 978-0-7453-3398-4.

- ^ Taylor, Matthew (28 July 2013). "Construction industry blacklisting is unacceptable, warns Vince Cable". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ "Crossrail blacklisting aired in Parliament". The Construction Index. 6 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Stein, Joshua (20 March 2023). "Sacked Crossrail spark blasts builders after blacklisting case settled". Construction News. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ "About Tunnel: The Archaeology of Crossrail". Crossrail Archaeology Museum. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ "Museum of London Docklands to reveal archaeological finds unearthed by the Crossrail project". crossrail.co.uk. 29 December 2022. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017.

- ^ McDermott, Josephine (10 February 2017). "A vignette of life in the past". BBC News.

- ^ Eleftheriou, Krista (15 March 2013). "14th century burial ground discovered in Central London" (Press release). Crossrail. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ Berkin, Chris (15 March 2013). "Crossrail discovers Black Death burial ground". Construction News. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ "Crossrail dig unearths 13,000 Victorian jam jars". BBC News. 11 January 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ "Crossrail Project Update". Crossrail. 29 December 2022. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019.

- ^ "Trial Operations underway ahead of Elizabeth line opening next year". Crossrail. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Farrell, Sean; Topham, Gwyn (8 November 2019). "Crossrail faces further delays and will cost more than £18bn". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ "Crossrail delayed until 2021 as costs increase". BBC News. 8 November 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ "Funding". Crossrail Ltd. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "Crossrail opening delayed again due to coronavirus". The Guardian. London. 23 July 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ "'It has to be flawless': long wait for London's Elizabeth line is nearly over". The Guardian. London. 8 February 2022.

- ^ "Crossrail needs extra £450m and delayed until 2022". BBC News. 21 August 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ "New modern ticket hall with step-free access opens at Moorgate as part of Elizabeth line improvements". Rail Business Daily. 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Crossrail Project Update". Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "Elizabeth line to open on 24 May 2022" (Press release). Transport for London. 4 May 2022. Archived from the original on 4 May 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Central and South East Stations". Crossrail. Archived from the original on 25 October 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "42 kilometers of new rail tunnels under London". Crossrail. 2013. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ "Farringdon Station". Crossrail. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Liverpool Street Station". Crossrail. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Western section – Paddington to Heathrow and Reading". Crossrail. Archived from the original on 25 June 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "SAFEGUARDING DIRECTIONS FOR DEVELOPMENT AFFECTING THE ROUTE AND ASSOCIATED WORKS PROPOSED FOR THE CROSSRAIL PROJECT – MAIDENHEAD TO OLD OAK COMMON, OLD OAK COMMON TO ABBEY WOOD, STRATFORD TO SHENFIELD AND WORKS AT WEST HAM, PITSEA AND CLACTON-ON-SEA" (PDF). Archived from the original (.doc) on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ Owen, Ed (23 July 2009). "Crossrail to Reading would keep it on track". New Civil Engineer.

- ^ Rail Utilisation Strategy, 2011, page 9

- ^ "London Crossrail plans extended to Reading". BBC News. 27 March 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ "Crossrail extended to Reading". Department for Transport. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ "DfT and TfL extend Crossrail route to Reading" (Press release). Transport for London. 27 March 2014.

- ^ "First Crossrail tracks laid on Stockley Flyover bridge". BBC News. 24 November 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ^ "New train underpass at Acton reaches structural completion". Archived from the original on 29 December 2016.

- ^ "Network Rail completes £100m of upgrades over Christmas". Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ "Eastern section – Stratford to Shenfield". Crossrail. Archived from the original on 25 June 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Smith, Howard. "Crossrail – Moving to the Operating Railway Rail and Underground Panel 12 February 2015" (PDF). 12 February 2015. Transport for London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ "About Crossrail Ltd". Crossrail. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ Jobson, Robert (23 February 2016). "Crossrail named the Elizabeth line: Royal title unveiled as the Queen visits Bond Street station". Evening Standard. London. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Crossrail to be named Elizabeth line in honour of the Queen". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ "Elizabeth line Design Idiom" (PDF). Transport for London. 6 December 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ Edwards, Tom (27 April 2011). "Crossrail brings old tunnel back to life". BBC London. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ "Building the Rail Tunnels". Crossrail. 2015. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ Boagey, Andrew; Genain, Marc (13 March 2009). "London's cross-city line follows the RER model". Railway Gazette International. London. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ May, Jack (11 January 2017). "To RER A, or to RER C? How Paris typifies the two models for cross-city commuter train lines". CityMetric. London. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ Bevan, Robert (14 October 2014). "The man who's setting the Crossrail style: Julian Robinson". Evening Standard. London. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Gregory, Elizabeth (26 May 2022). "Art on the Elizabeth Line: travel on London's newest public gallery". Evening Standard. London. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Hyde, John (16 March 2011). "Crossrail 'mock-ups' for stations that will last 100 years". The Docklands. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011.

- ^ "Future of London transport revealed at secret site". BBC News. 16 March 2011. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Dempsey, Andrew (11 November 2017). "Over 1.5 kilometres of escalators now installed in Elizabeth line stations – Crossrail". Crossrail. Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Accessibility on the Elizabeth line". Transport for London. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Elizabeth line stations". Transport for London. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

We refurbished many of the existing stations that are now served by the Elizabeth line. Alongside Network Rail, we: Built new station buildings and improved others with features like brighter and more spacious ticket halls and waiting areas, Created step-free access at every station with new lifts and footbridges, Refurbished waiting rooms and toilets as well as platform shelters and canopies, Added platform enhancements such as new signage, help points, information screens and CCTV

- ^ "Campaigners celebrate their Crossrail access win as line finally opens, eight years on". Disability News Service. 26 May 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Rail Networks Connection Agreement in respect of a connection between the Network Rail Network and the Crossrail Central Operating Section at Pudding Mill Lane Junction" (PDF). Office of Rail and Road. 24 January 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ "Now it's 2019: Crossrail's stealth delay". BorisWatch (blog). 8 June 2011.

- ^ "Crossrail starts tender process for signalling system" (Press release). Crossrail. 14 April 2011. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

- ^ "Crossrail Rolling Stock Tender is Issued". London Reconnections (blog). 1 December 2010.

- ^ "Could we finally see the end of overcrowded trains?". BBC News. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ^ "Route Window NE9 Romford station and depot (east)" (PDF). Crossrail. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ^ "Transforming East London Together 2013–2023" (PDF). London City Airport. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ "Examination of the London Borough of Newham – Detailed Sites and Policies Development Plan Document – Written Statement of London City Airport" (PDF). London Borough of Newham. 11 April 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ "Silvertown Station – Crossrail Proposals" (PDF). Crossrail. 17 January 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2015.

- ^ Broadbent, Giles (31 May 2016). "Why is TfL so hostile to a Crossrail station at LCY?". The Wharf. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Horgan, Rob; Smale, Katherine (20 April 2018). "London City Airport – Crossrail 'a missed opportunity'". New Civil Engineer.

- ^ "London City Airport CEO says Crossrail isn't essential to its success". InYourArea.co.uk. 12 February 2018.

- ^ Smale, Katherine (21 May 2019). "London City Airport in talks with TfL about Crossrail station". New Civil Engineer. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Old Oak Common". High Speed 2. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Have your say on plans to transform Old Oak and Park Royal". London.gov.uk (Press release). London City Hall. 5 February 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ^ "'World Class' Old Oak Common images unveiled by HS2". railnews.co.uk. 5 February 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Construction of HS2's Old Oak Common station to be given the go-ahead". ITV News. 23 June 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ "Transport Secretary to give the go-ahead for start of permanent works on HS2's west London 'super-hub' station". HS2. June 2021.

- ^ Rail Utilisation Strategy, 2011, page 153.

- ^ "Round 1 Consultation Panels Generic Information" (PDF). Crossrail Learning Legacy. September 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Developing Crossrail – Round 2 Consultation Document – August to October 2004" (PDF). Crossrail Learning Legacy. August 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ a b Smale, Katherine (27 March 2019). "Crossrail extension to Ebbsfleet buoyed by government fund". New Civil Engineer. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Harris, Tom (6 February 2008). "Crossrail Safeguarding Update 2008". Department for Transport. Archived from the original on 7 June 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- ^ "C2E Crossrail to Ebbsfleet". c2e-campaign. Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Calls for Crossrail's 'missing link' to be extended to south London and Kent". Evening Standard. London. 11 October 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "'Important' Crossrail extension through Dartford listed as priority for government". News Shopper. 9 January 2018.

- ^ "Elizabeth Line extension plans east of Abbey Wood back in the spotlight". City AM. 12 January 2018. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ "Mayor's Transport Strategy" (PDF). London.gov.uk. March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Government response to the Thames Estuary 2050 Growth Commission" (PDF). Government of the United Kingdom. March 2019.

- ^ "Crossrail Safeguarding Directions Abbey Wood to Gravesend and Hoo Junction (Volume 4)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Rail Utilisation Strategy, 2011, page 150.

- ^ "'Emerging scenario' suggests Crossrail to the West Coast Main Line". Rail. Peterborough. 10 August 2011. p. 8.

- ^ "Crossrail extension to Hertfordshire being considered". BBC News. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Topham, Gwyn (7 August 2014). "New Crossrail route mooted from Hertfordshire into London". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ "Crossrail off the tracks as plans are shelved". Hemel Today. Johnston Publishing. 5 August 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ^ "Service Opportunities". Heathrow Southern Railway. 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Lo, Hsin-Yi (9 February 2018). "Extend Crossrail to Southend Airport". Southend Echo. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Council launches campaign to extend Crossrail to Southend-on-Sea". Rail Technology Magazine. 1 November 2018. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Mayor of London – https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/planning/implementing-london-plan/mayoral-community-infrastructure-levy

- ^ "The future of Crossrail". House of Commons. 5 November 2007.

- ^ a b "Greater Anglia Franchise Invitation to Tender 21 April 2011" (PDF). Department for Transport. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2011.

- ^ a b c "MTR selected to operate Crossrail services". Railway Gazette International. London. 18 July 2014. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ "Crossrail moves forward with major train and depot contract" (Press release). Crossrail. 1 December 2010. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011.

- ^ "TfL Board Meeting Summary: DLR, Overground and Other Ways of Travelling". London Reconnections (blog). 2 October 2008. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010.

- ^ "Greater Anglia Franchise Consultation January 2010" (PDF). Department for Transpprt. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2011.

- ^ Rennie, Kim (2022). "London's newest railway – The Elizabeth line opens". Underground News. No. 728. pp. 468–469. ISSN 0306-8617.

General and cited sources

[edit]- "London & South East RUS (final)". Network Rail. 28 July 2011. p. 9. Archived from the original on 28 November 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- "Crossrail Act 2008". The National Archives.

- "Crossrail Bill supporting documents". Archived from the original on 13 February 2009.

- "Government backs £10bn Crossrail". BBC News. 20 June 2004.

- Geoghegan, Tom (20 June 2004). "Will Crossrail beat the Tube?". BBC News.

- "Crossrail link 'to get go-ahead'". BBC News. 13 February 2005.

- "First Crossrail bill for Commons". BBC News. 22 February 2005.

- "Election holds up Crossrail bill". BBC News. 7 April 2005.

- "Crossrail plan in Queen's Speech". BBC News. 17 May 2005.

- "Crossrail's giant tunnelling machines unveiled". BBC News. 2 January 2012.

- "Crossrail: A rare look deep under London" (video). BBC News. 25 January 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2013.