National Tramway Museum

Crich Tramway Village | |

The museum features working trams in a traditional street setting. A line up of such trams is seen here at Town End terminus | |

| |

| Established | 1963 |

|---|---|

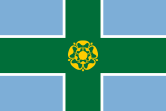

| Location | Crich, Derbyshire, England |

| Coordinates | 53°05′21″N 1°29′11″W / 53.08930°N 1.48632°W |

| Type | Transport museum |

| Owner | Tramway Museum Society |

| Website | tramway.co.uk |

The National Tramway Museum (trading as Crich Tramway Village) is a tram museum located at Crich (), in the Peak District of Derbyshire, England. The museum contains over 80 (mainly British) trams built between 1873 and 1982 and is set within a recreated period village containing a working pub, café, old-style sweetshop and tram depots. The museum's collection of trams runs through the village-setting with visitors transported out into the local countryside and back and is operated by the Tramway Museum Society, a registered charity.[1][2][3][4]

The Crich Tramway Village remains an independent charity, which receives no funding from the state or local government and relies on the voluntary contribution made by members of the Tramway Museum Society and its visitors.[5]

History of the museum

[edit]History of the site

[edit]

George Stephenson, the great railway pioneer, had a close connection with Crich and the present (2008) tramway follows part of the mineral railway he built to link the quarry with Ambergate.[6][7]

While building the North Midland Railway from Derby to Rotherham and Leeds, Stephenson had found rich coal seams in the Clay Cross area and he saw a new business opportunity. Crich was already well known for the quality of the limestone and Stephenson recognised that he could use the local coal and limestone to produce burnt lime for agricultural purposes, and then use the new railway to distribute it. Cliff Quarry, where the museum is now located, was acquired by Stephenson's company and to link the quarry with limekilns he had built at Ambergate, Stephenson constructed a 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) gauge line – apparently the first metre gauge railway in the world. Stephenson lived the last 10 years of his life in Chesterfield, often bringing visitors to Crich to see the mineral railway. He died in 1848 and is buried in Holy Trinity Church, Chesterfield.[6][8]

Cliff Quarry remained in use until it closed in 1957/8, and shortly afterwards part of it was acquired for use by the museum. Other parts of the quarry, now known as Crich Quarry, reopened in the 1960s and was then operated by RMC and Tarmac. In 2000 ownership of the active quarry site was transferred to Bardon Aggregates, who closed the quarry in 2010. It remains closed.[9]

Tramway Museum Society

[edit]

In the period after the Second World War, when most of the remaining British tramways were in decline or actually closing, the first event in the history of the National Tramway Museum took place. A group of enthusiasts on a farewell tour of Southampton Tramways in August 1948 decided to purchase one of the open top trams on which they had ridden. For the sum of £10 they purchased number 45 – now included in collection at the museum. From this purchase grew the idea of a working museum devoted to operating tramcars. From the original group developed the Tramway Museum Society, established in 1955, incorporated as a company limited by guarantee in 1962, and recognised as an educational charity in 1963.[10]

Acquisition of the site

[edit]

After a sustained search across the country, in 1959 the society's attention was drawn to the then derelict limestone quarry at Crich in Derbyshire, from which members of the Talyllyn Railway Preservation Society were recovering track from Stephenson's mineral railway for their pioneering preservation project in Wales. After a tour of the quarry, members of the society agreed to lease – and later purchase – part of the site and buildings. Over the years, by the efforts of the society members, a representative collection of tramcars was brought together and restored, tramway equipment was acquired, a working tramway was constructed and depots and workshops were built. Recognising that tramcars did not operate in limestone quarries, the society agreed in 1967 to create around the tramway the kind of streetscape through which the trams had run and thus the concept of the Crich Tramway Village was born. Members then turned their attention to collecting items of street furniture and even complete buildings, which were then adapted to house the Museum's collections of books, photographs and archives.[10]

Timeline

[edit]

- 1963 – First horse tram service[10][11]

- 1964 – First electric tram service[10]

- 1968 – The line was extended to Wakebridge, and the first Grand Transport Extravaganza held, in what was to become an annual event[7][12]

- 1969 – Opening of purpose built workshops[10]

- 1975 – The Duke of Gloucester become Patron of the Society[10]

- 1976 – The re-erected facade of Derby Assembly Rooms was opened by the Duke of Gloucester.[13]

- 1978 – Opening of scenic tramway to Glory Mine[7]

- 1982 – First phase of museum library opened[10]

- 1985 – Museum loans trams to Blackpool for Electric Tram Centenary[10]

- 1988 – Museum loans trams for Glasgow Garden Festival[10][14]

- 1990 – Museum loans trams for Gateshead Garden Festival[15]

- 1991 – Exhibition Hall inaugurated[10]

- 1997 – First AccessTram for visitors with disabilities[10]

- 2002 – Opening of Workshop Viewing Gallery and Red Lion Pub[16][17]

- 2004 – Woodland Walk and Sculpture Trail inaugurated by the Dowager Duchess of Devonshire[10]

- 2010 – Opening of new "Century of Trams" exhibition in main Exhibition Hall[10]

- 2011 – Opening of refurbished George Stephenson Workshop[10]

- 2014 – Passengers able to alight at Glory Mine for the first time[18]

The museum's site

[edit]

The museum site is made up of a number of different areas, with the museum's tramway passing either through or adjacent to all of them. The museum's main entrance delivers visitors to the Victoria Park area, but the trams start their journey at Town End, a walk or short tram ride under the Bowes Lyon Bridge and down Period Street.[18]

Period Street

[edit]

The running line of the tramway starts from a stub terminus at Town End where outbound trams board passengers, having first disembarked inbound passengers at Stephenson Place. The first 500 metres (1,600 ft) of line is double track, laid in a setted street, and this is known as the Period Street. It has broad footpaths on both sides and is flanked by a number of old buildings and street furniture elements. The street scene is closed off by the Bowes-Lyon Bridge, which the tramway passes under.[7][19]

Amongst the buildings and furniture in the street are:

- the grade II listed 1763 facade of the Derby Assembly Rooms, moved to the site in 1975–76. The modern building behind this facade houses a number of small exhibitions and the Tramway Museum Society's library.[20]

- the original workshop of Stephenson's railway, now housing the Stephenson Discovery Centre.[20]

- the Red Lion pub, relocated from Stoke on Trent and still serving its original purpose, together with the museum's café.[21]

- a cast iron and glass tram shelter, thought to originate in Birmingham, at the Town End tram stop[22]

- a Bundy clock, originally used in West Bromwich to regulate departure times of trams from termini.[23]

- a cast iron urinal, originally located at the Erleigh Road terminus of Reading Corporation Tramways.[24]

- a police box dating from the 1930s and a police call post dating from the 1920s. Both were formerly used by the London's Metropolitan Police and are grade II listed.[25]

- a Penfold pillar box, dating from 1872 to 1879, and a K1 telephone box, dating from 1921. Both were used by the Post Office and are grade II listed.

Stephenson Workshop and Discovery Centre

[edit]

One of the few buildings on the site that predate the creation of the museum and are in their original place, the Stephenson Workshop was built in the 19th century and was used as a smithy and wagon works for George Stephenson's metre gauge mineral railway. Originally known as the Stone Workshop, the building has been fully restored and is now home to a state of the art learning facility on the ground floor and the Stephenson Discovery Centre on the first floor.[20][26]

The Stephenson Discovery Centre explains the early history of the museum site, including the story of George Stephenson and his acquisition of Cliff Quarry and construction of the mineral railway. It also describes how overcrowding in expanding towns and cities paved the way for in the introductions of trams to Britain in the 19th century. A modern glass bridge from the upper floor provides access to the viewing gallery of the tram workshop (see below).[20][26]

Tram Depot and Exhibition Hall

[edit]

The tram depot is situated at the further end of the museum's Period Street, just before it passes under the Bowes-Lyon Bridge. The tram depot houses most of the museum's fleet of trams, including the running fleet when not in operation, other than those displayed in the exhibition hall, which faces the depot across the depot yard. The depot has 18 tracks, with each track able to accommodate several trams. The first 10 tracks are directly accessible from the depot yard, while tracks 11 to 18 are accessed via a traverser, which also provides rail access to the exhibition hall.[18][27]

The tram depot includes a workshop, on tracks 1 to 3, used for the maintenance of the tram fleet. This has a viewing gallery, accessed by a glass bridge from the upper floor of the Stephenson Discovery Centre, which allows visitors to watch the work going on below and displays small exhibits relating to this work.[20]

The exhibition hall presents the ‘Century of Trams’ exhibition, telling the story of a hundred years of tramway development, from 1860 – 1960, taking in horse trams, steam trams and electric trams. The story is told through the display of number of the museum's tram cars, together with interpretive panels, audio sounds to represent each decade of the timeline, and interactive displays.[20]

Bowes-Lyon Bridge and Victoria Park

[edit]

The Bowes-Lyon Bridge spans the end of the museum's period street, and provides both a vantage point and a visual closure to the recreated urban part of the museum. The bridge deck is constructed in cast iron and dates from 1844, when it was installed at the Bowes-Lyon Estate in St Paul's Walden, Hertfordshire. The bridge was donated to the museum in 1971, and subsequently re-erected at its present site. Embedded in the deck of the Bowes-Lyon Bridge is a stretch of horse-tram track, demonstrating the lightweight nature of such track when compared to that used by the electric trams on the lower level.[18][28]

Immediately to the north and west of the bridge is Victoria Park, a recreated Victorian era public park. This has, as its centrepiece, a bandstand that was erected here in 1978 but was previously at Longford Park in Stretford, Greater Manchester. From the park, a path leads to the museum's Woodland Walk and Sculpture Trail. Alongside the park is a tram stop, served by both inbound and outbound trams and named after the park. To the east of the park, on the opposite side of the tramway, is the museum entrance.[18][29]

Wakebridge and Glory Mine

[edit]

Just past the Victoria Park tram stop, the museum's running track transitions from grooved tram track set in a road surface to sleeper track and becomes single track. The line passes between woodland to the west and the now disused Cliff Quarry to the east, before arriving at the Wakebridge passing loop and tram stop.[18]

The stop has a selection of shelters and simple buildings, including the Birmingham Tram Shelter, the Bradford Cabmans Shelter, and the Octogon, together with the line's electrical sub-station. A path leads to the museum's Woodland Walk and Sculpture Trail. Adjacent to the stop, the Peak District Mines Historical Society has created an exhibition of mining equipment, including the mouth of a drift mine with a battery powered locomotive coming out of it, and a shop selling mineral samples, books and gemstones.[18][30][31][32]

Beyond Wakebridge, the line runs along an exposed hillside with vistas across the valley of the River Derwent, which is here part of the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site. While now largely rural, this valley was one of the cradles of the Industrial Revolution, where the modern factory system was introduced during the 18th century to take advantage of Richard Arkwright's invention of the water frame for spinning cotton.[33]

At the end of the line is the Glory Mine tram stop and passing loop. A public footpath crosses the line, giving access to Crich Stand.[7][18][34]

Woodland Walk and Sculpture Trail

[edit]

The Woodland Walk and Sculpture trail connects the tram stops at Victoria Park and Wakebridge, passing through the mixed woodland that is native to the limestone geology of the Crich area. Tree cover is mostly ash, but also includes sycamore, alder and silver birch, with a shrub layer of hazel, wych elm, wild rose, elder and hawthorn. The combination of the ash canopy and limestone results in a range of ground-cover plants including primrose, early purple orchid, cowslip, marjoram, garlic and strawberries.[35]

Most of the sculptures along the trail were carved by the sculptor, Andrew Frost, using a chainsaw and carving a basic shape from a tree trunk before working on the detail. Such sculptures do not last forever, with wood splitting, fungi and the claws of badgers all contributing to their deterioration. The sculpture trail is therefore always evolving, as old sculptures are removed and new ones added.[35]

Also to be spotted in the Woodland Walk is a stretch of the original narrow-gauge track as used in the old quarry, and a labyrinth made from old stones left in the quarry. There are views down into the valley of the River Derwent and up to Crich Stand.[35]

The museum's tramcar fleet

[edit]

The museum has over 80 tramcars in its collection. The majority of these are electric double-decker trams built between 1900 and 1930 for use in a large selection of British towns and cities, but the collection also includes earlier horse and steam hauled trams, more modern trams, and trams built for a number of cities across the world.[1][36]

Many of the cars are in operable condition, and are used on the museum's running line, whilst others are restored in static condition and are displayed in the museum's display hall or elsewhere on the site. A few are stored in unrestored condition, some of these being at the museum's off-site store at Clay Cross.

Among this fleet are:

- Southampton 45, built in 1903, was the very first tramcar to be preserved by the Tramway Museum Society, purchased for just £10 in 1949, after the closing ceremony of the Southampton Corporation.[37][38]

- Sheffield 15, a horse-drawn tram dating from 1874, was the first tram to operate at the museum, in 1963 and before the electric overhead was erected. The car still operates on a few 'horse tram' days a year.[39]

- Blackpool and Fleetwood 2, a single deck tram built in 1898, was the first electric tram to carry passengers at the museum, in 1964.[40]

- Blackpool 4 is the oldest electric tram in the collection and built in 1885 for the opening of Britain's first electric street tramway. Stored, and then preserved, by Blackpool tramways, it has been in the care of the museum since 1973.[41]

- London United Tramways 159, an electric tram built in 1902 to a particularly luxurious specification to serve London's affluent western suburbs, between Hampton Court, Hammersmith and Wimbledon.[42]

- Chesterfield 7, an electric tram built in 1904, survived a depot fire which destroyed many other trams and was also used as a house after withdrawal. The museum found the tram and restored it.[43]

- Metropolitan Electric Tramways 331, built in 1930 as a prototype for the fleet of Feltham cars that served London's northern suburbs until the 1950s.[44]

- Glasgow 1282, a "Coronation" streamliner, built in 1940 and survived to run in the closing procession in 1962. Built to a very high specification and described as the finest short stage carriage vehicles in Europe.[45]

- Sheffield 510, which entered service in 1950 and was withdrawn, still almost brand-new, when the city's tram system closed in 1960. Car 510 was specially decorated for the occasion as Sheffield's last tram, and still retains this decoration.[43]

- Prague 180, built in 1908, was gifted to the museum during the Prague Spring and transported to Crich days before the subsequent Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia. It became a symbol of the plight of the country.[43]

- Den Haag Tramways No. 1147, built in 1957 in Belgium for a Dutch tramway to the classic US PCC design. This car presages the modern tram cars that are to be seen around the world today, including on the UK's second generation tramways.[46]

The museum's tramway

[edit]Crich Tramway Village Running Line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Running line

[edit]

The running line of the tramway is approximately 1.6 kilometres (0.99 mi) long. The line starts from a stub terminus at Town End where outbound trams board passengers, having first disembarked inbound passengers at Stephenson Place. From Town End, about the first 500 metres (1,600 ft) of line is double track, laid in a setted street, flanked by the buildings of the recreated period village, and including the inbound-only Stephenson Place tram stop. The street scene is closed off by the Bowes-Lyon Bridge, which the line crosses under on interlaced track. Just before the bridge, a junction gives access to the depot and yard.[7]

On the far side of the bridge the line returns to double track and calls at the Victoria Park tram stop, which serves both the recreated Victorian-era public park of the same name, and the main entrance to the site from the car park. The double track continues for another 240 metres (790 ft) before converging into single track that continues as far as the Wakebridge tram stop and passing loop, which is located some 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) from Town End. Beyond the passing loop, the track returns to single track as far as the Glory Mine tram stop and terminus, where there is a further passing loop and a headshunt, together with a siding.[7]

Passenger services

[edit]

The tramway is generally operated whenever the museum is open. Depending on the time of year and level of demand, a two or three car service is normally provided. If a two car service is operated, trams pass on the double-track section in the street. If three trams are in service, trams pass both in the loop at Wakebridge and in the street.[7]

On special occasions, up to 18 tramcars can be operated, with trams operating in convoys of two or three through the single track sections. The convoys pass each other on the in the street, at Wakebridge, and at Glory Mine terminus.[7]

The tramway has a 1969 tram from Berlin, which has been converted to allows visitors with disabilities to travel the line, with the provision of a wheelchair lift and wider doors.

Methods of current collection

[edit]Most of the museum's trams are electric trams which were designed to be powered by an overhead wire system using one of, or a combination of, trolley poles, bow collectors or pantographs. The museum's overhead wire system has been built so that trams with any of those types of current collection can be used. The current is supplied at 600 volts DC.[7][47][48]

Other forms of current collection were used by electric trams, especially in the early days of such tramways, and the museum has non-operational displays of several of them:

- Conductors set in steel troughs under the roadway, as used on the UK's first street running electric tramway at Blackpool, and represented in Crich by the display of Blackpool 4 in the Exhibition Hall.[49]

- The stud contact system, as demonstrated with a dummy stud between the rails in the yard. This is the only known example of this form remaining, and is from Wolverhampton.[citation needed]

Access to the museum

[edit]The museum is open from early March to early November on every day of the week except Fridays, and also on Fridays during bank and school holidays. The museum opens at 10:00 and closes at 16:30 on weekdays or 17:30 on weekends and bank holidays.[50]

The museum is some 18 kilometres (11 mi) north of Derby, 32 kilometres (20 mi) south of Sheffield, 66 kilometres (41 mi) south-east of Manchester, and 200 kilometres (120 mi) north-west of London. There is a large on-site car park.[50]

The nearest railway station is Whatstandwell, on the Derwent Valley Line from Derby to Matlock, from which there is a steep uphill walk of about 1 mile (1.6 km) to the museum. The museum is also directly served by roughly hourly bus services from Matlock and Alfreton, and less frequent services from Belper and Ripley. There is no bus service on Sundays.[50]

In the media

[edit]The museum features in the opening of the 1969 film Women in Love, and as one of the locations in the 2012 film Sightseers.[51][52]

The museum, under its old name of Crich Tramway Museum, also features in the lyrics of the John Shuttleworth song "Dandelion and Burdock".[53]

See also

[edit]- Listed buildings in Crich

- Beamish Museum, in County Durham

- Light Rail Transit Association

- Maley & Taunton

- Scottish Tramway and Transport Society

- Summerlee Heritage Park (Coatbridge)

- The Trolleybus Museum at Sandtoft, in Lincolnshire

- Wirral Tramway, in Birkenhead on Merseyside

Gallery

[edit]-

London tram 1622 leaving the depot.

-

Glasgow Tram 22.

-

A 1925 Leeds tram at Victoria Park, at the entrance to the Village

-

A 1936 Liverpool streamlined tram outside the reconstructed Derby Assembly Rooms at Crich Town End

-

Night scene with early London tramcar.

-

The tram sheds

-

Tram shelter.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "The Tramcar Collection". Crich Tramway Village. Archived from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "Village Scene". Crich Tramway Village. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ "Ride the Trams". Crich Tramway Village. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ "The Tramway Museum Society". Charity Commission. Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ "Make a Donation". Crich Tramway Village. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Crich Heritage Report". Amber Valley Borough Council. pp. 24–25. Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hollis, EJ (14 March 2006). "A survey of UK tram and light railway systems relating to the wheel/rail interface". Health & Safety Laboratory. pp. 147–161. Archived from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ "George Stephenson". Spartacus Educational Publishers Ltd. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ "Crich Quarry". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Our Story". The Tramway Museum Society. Archived from the original on 22 February 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ "Derbyshire tram museum at Crich celebrates 50 years". BBC News. 8 July 2013. Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ Brooks, Donald (August 2019). "Quarry Railway with a Difference". Narrow Gauge World. Warners Group Publications Plc. pp. 23–25.

- ^ "Facade of the former Derby Assembly Rooms at the National Tramway Museum". 13 August 1985. Archived from the original on 4 March 2024. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ Prior, Gareth (17 October 2019). "Picture in Time: Glasgow 22". Archived from the original on 22 February 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Prior, Gareth (17 June 2022). "Picture in Time: Gateshead Garden Festival – Sunderland 100". Archived from the original on 22 February 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ "Tramway Village Spend Lottery Grant with Morris". Morris Material Handling. 27 February 2002. Archived from the original on 4 March 2024. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Red Lion Hotel, Crich". WhatPub. CAMRA. Archived from the original on 4 March 2024. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Visitor's Guide to…Crich Tramway Village". British Trams Online. Archived from the original on 5 March 2024. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ "Village Scene". Crich Tramway Village. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Exhibitions". Crich Tramway Village. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ "Red Lion". Crich Tramway Village. Archived from the original on 23 May 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ "Crich tram shelter 1". The Scottish Ironwork Foundation. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ "New season of fun family events and entertainment at Crich Tramway Village – hop on board now". Derbyshire Times. 15 March 2024. Archived from the original on 23 May 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ "Did You Know – Reading Urinal". Crich Tramway Village. 12 May 2017. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ "Time Stands Still for Police Box at Crich Tramway Village". Crich Tramway Village. 1 July 2022. Archived from the original on 23 May 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Tramway Museum wins National Building Excellence Award for new discovery centre". Derbyshire Times. 5 December 2012. Archived from the original on 23 May 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ "Traverser Returns". Crich Tramway Village. 21 February 2019. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Bowes-Lyon Bridge". Open Plaques. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Longford Conservation Area Conservation Area Appraisal" (PDF). Trafford Council. October 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Winter Outside Working". Crich Tramway Village. 12 November 2018. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Restoration of a 19th Century Bradford Cabmen's Shelter Project". Crich Tramway Village. 23 December 2020. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Crich Project and Lead Mining Display". Peak District Mines Historical Society. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "World Heritage Committee Inscribes 31 New Sites on the World Heritage List". UNESCO. December 2001. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

- ^ Explorer 269 – Chesterfield & Alfreton (Map). Ordnance Survey. 16 September 2015. ISBN 978-0-319-24466-1.

- ^ a b c "The Woodland Walk and Sculpture Trail" (PDF). 4. Crich Tramway Village and The Countryside Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2024. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ "Crich Tramway Village". British Trams Online. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ "Official Fleetlist". Archived from the original on 1 April 2009.

- ^ "Southampton 45 Profile". Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ "Sheffield Corporation Tramways No. 15". Crich Tramway Village. Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ "Blackpool & Fleetwood Tramroad No. 2". Crich Tramway Village. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ "Blackpool Electric Tramway Company Ltd. No. 4". Crich Tramway Village. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ "London United Tramways No. 159". Crich Tramway Village. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Crich Tramway Village Guidebook, 2003–2008 Edition. National Tramway Museum. 2003–2008.

- ^ "'Metropolitan Electric Tramways No. 331". Crich Tramway Village. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Glasgow Corporation Transport No. 1282". Crich Tramway Village. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ "Den Haag Tramways No. 1147". Crich Tramway Village. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Methods of Current Collection". Archived from the original on 29 April 2007.

- ^ David Tudor. The tram driver. p. 10.

- ^ "Blackpool Electric Tramway Company Ltd. No. 4". Crich Tramway Village. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ a b c "How To Find Us". Crich Tramway Village. Archived from the original on 2 March 2024. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ "Women in Love". The Worldwide Guide To Movie Locations. Archived from the original on 23 February 2024. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ "Sightseers". British Railway Movie Database. Archived from the original on 23 February 2024. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ "John Shuttleworth – Dandelion & Burdock Lyrics". SongLyrics. Archived from the original on 23 February 2024. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- The London County Council Tramways Trust —- responsible for the restoration of London nos. 1, 106, 159, 1622

- Photographs and Information from Strolling Guides

- Tram Travels: Crich Tramway Village