Brunei

Brunei Darussalam Negara Brunei Darussalam (Malay) | |

|---|---|

Motto:

| |

Anthem:

| |

| Capital and largest city | Bandar Seri Begawan 4°53.417′N 114°56.533′E / 4.890283°N 114.942217°E |

| Official language | Malay[1] |

| Other languages and dialects[2][3][4] | |

| Official scripts | |

| Ethnic groups (2023)[6] | |

| Religion (2021)[6] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Bruneian |

| Government | Unitary Islamic absolute monarchy |

• Sultan and Prime Minister | Hassanal Bolkiah |

• Crown Prince and Senior Minister | Al-Muhtadee Billah |

| Legislature | none[a] |

| Formation | |

| c. 1368 | |

| 17 September 1888 | |

• Independence from the United Kingdom | 1 January 1984 |

| Area | |

• Total | 5,765[10] km2 (2,226 sq mi) (164th) |

• Water (%) | 8.6 |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 460,345[11] (169th) |

• 2016 census | 417,256 |

• Density | 72.11/km2 (186.8/sq mi) (134th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| HDI (2022) | very high (55th) |

| Currency | Brunei dollar (BND) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (Brunei Standard Time) |

| Drives on | left |

| Calling code | +673[c] |

| ISO 3166 code | BN |

| Internet TLD | .bn[14] |

| |

Brunei,[b] officially Brunei Darussalam,[c][d] is a country in Southeast Asia, situated on the northern coast of the island of Borneo. Apart from its coastline on the South China Sea, it is completely surrounded by the Malaysian state of Sarawak, with its territory bifurcated by the Sarawak district of Limbang. Brunei is the only sovereign state entirely on Borneo; the remainder of the island is divided between its multi-landmass neighbours of Malaysia and Indonesia. As of 2023[update], the country had a population of 455,858,[11] of whom approximately 180,000 resided in the capital and largest city of Bandar Seri Begawan. Its official language is Malay and Islam is the state religion of the country, although other religions are nominally tolerated. The government of Brunei is a constitutional absolute monarchy ruled by the Sultan, and it implements a fusion of English common law and jurisprudence inspired by Islam, including sharia.

At the Bruneian Empire's peak during the reign of Sultan Bolkiah (1485–1528), the state is claimed to have had control over the most of Borneo, including modern-day Sarawak and Sabah, as well as the Sulu archipelago and the islands off the northwestern tip of Borneo. There are also claims to its historical control over Seludong, the site of the modern Philippine capital of Manila, but Southeast Asian scholars believe the name of the location in question is actually in reference to Mount Selurong, in Indonesia.[18] The maritime state of Brunei was visited by the surviving crew of the Magellan Expedition in 1521, and in 1578 it fought against Spain in the Castilian War.

During the 19th century, the Bruneian Empire began to decline. The Sultanate ceded Sarawak (Kuching) to James Brooke and installed him as the White Rajah, and it ceded Sabah to the British North Borneo Chartered Company. In 1888, Brunei became a British protectorate and was assigned a British resident as colonial manager in 1906. After the Japanese occupation during World War II, a new constitution was written in 1959. In 1962, a small armed rebellion against the monarchy which was indirectly related to the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation was ended with British assistance and led to the ban of the pro-independent Brunei People's Party. The revolt had also influenced the Sultan's decision not to join the Malaysian Federation while it was being formed. Britain's protectorate over Brunei would eventually end on 1 January 1984, becoming a fully sovereign state.

Brunei has been led by Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah since 1967, and the country's unicameral legislature, the Legislative Council, is simply consultative and are all appointed by the Sultan. The country's wealth derives from its extensive petroleum and natural gas fields. Economic growth during the 1990s and 2000s has transformed Brunei into an industrialised country, with its GDP increasing 56% between 1999 and 2008. Political stability is maintained by the House of Bolkiah by providing a welfare state for its citizens, with free or significant subsidies in regards to housing, healthcare and education. It ranks "very high" on the Human Development Index (HDI)—the second-highest among Southeast Asian states after Singapore, which it maintains close relations with including a Currency Interchangeability Agreement. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Brunei is ranked ninth in the world by gross domestic product per capita at purchasing power parity. Brunei is a member of the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, the East Asia Summit, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, the Non-Aligned Movement, the Commonwealth of Nations, and ASEAN.

Etymology

According to local historiography, Brunei was founded by Awang Alak Betatar, later to be Sultan Muhammad Shah, reigning around AD 1400. He moved from Garang in the Temburong District[19] to the Brunei River estuary, discovering Brunei. According to legend, upon landing he exclaimed, Baru nah (loosely translated as "that's it!" or "there"), from which the name "Brunei" was derived.[20] He was the first Muslim ruler of Brunei.[21] Before the rise of the Bruneian Empire under the Muslim Bolkiah dynasty, Brunei is believed to have been under Buddhist rulers.[22]

It was renamed "Barunai" in the 14th century, possibly influenced by the Sanskrit word "varuṇ" (वरुण), meaning "seafarers".[23] The word "Borneo" is of the same origin. In the country's full name, Negara Brunei Darussalam, darussalam (Arabic: دار السلام) means "abode of peace", while negara means "country" in Malay. A shortened version of the Malay official name, "Brunei Darussalam", has also entered common usage, particularly in official contexts, and is present in the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names geographical database,[24] as well as the official ASEAN[25] and Commonwealth[26] listings.

The earliest recorded documentation by the West about Brunei is by an Italian known as Ludovico di Varthema. On his documentation back to 1550;

We arrived at the island of Bornei (Brunei or Borneo), which is distant from the Maluch about two hundred miles [three hundred kilometres], and we found that it was somewhat larger than the aforesaid and much lower. The people are pagans and are men of goodwill. Their colour is whiter than that of the other sort ... in this island justice is well administered ...[27]

History

Early history

Areas comprising what is now Brunei participated in the Maritime Jade Road, as ascertained by archeological research. The trading network existed for 3,000 years, between 2000 BC to 1000 AD.[28][29][30][31] The settlement known as Vijayapura was a vassal-state to the Buddhist Srivijaya empire and was thought to be located in Borneo's Northwest which flourished in the 7th Century.[32] Vijayapura itself upon earlier in its history, was a rump state of the fallen multi-ethnic: Austronesian, Austroasiatic and Indian, Funan Civilization; previously located in what is now Cambodia.[33]: 36 This alternative Srivijaya known as Vijayapura referring to Brunei, was known to Arabic sources as "Sribuza".[34]

One of the earliest Chinese records of an independent kingdom in Borneo is the 977 AD letter to the Chinese emperor from the ruler of Boni, which some scholars believe to refer to Borneo.[35] The Bruneians regained their independence from Srivijaya due to the onset of a Javanese-Sumatran war.[36] In 1225, the Chinese official Zhao Rukuo reported that Boni had 100 warships to protect its trade, and that there was great wealth in the kingdom.[37] Marco Polo suggested in his memoirs that the Great Khan or the ruler of the Mongol Empire, attempted and failed many times in invading "Great Java" which was the European name for Bruneian controlled Borneo.[38][additional citation(s) needed]

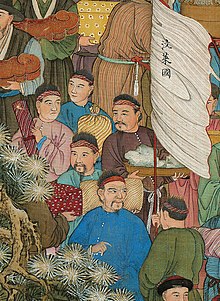

According to Wang Zhenping, in the 1300s, the Yuan Dade nanhai zhi or "Yuan dynasty Dade period southern sea records" reported that Brunei or administered Sarawak and Sabah as well as the Philippine kingdoms of Butuan, Sulu, Ma-i (Mindoro), Malilu 麻裏蘆 (Manila), Shahuchong 沙胡重 (Siocon or Zamboanga), Yachen 啞陳 Oton, and 文杜陵 Wenduling (Mindanao),[39] which would regain their independence at a later date.[40]

In the 14th century, the Javanese manuscript Nagarakretagama, written by Prapanca in 1365, mentioned Barune as the constituent state of Hindu Majapahit,[41] which had to make an annual tribute of 40 katis of camphor. In 1369, Sulu which was also formerly part of Majapahit, had successfully rebelled and then attacked Boni, and had invaded the Northeast Coast of Borneo[42] and afterwards had looted the capital of its treasure and gold including sacking two sacred pearls. A fleet from Majapahit succeeded in driving away the Sulus, but Boni was left weaker after the attack.[43] A Chinese report from 1371 described Boni as poor and totally controlled by Majapahit.[44] When the Chinese admiral Zheng He visited the Brunei in the early 15th century, he founded a major trading port which included Chinese people who were actively trading with China.[45]

During the 15th century, Boni had seceded from Majapahit and then converted to Islam. Thus transforming into the independent Sultanate of Brunei. Brunei became a Hashemite state when she allowed the Arab Emir of Mecca, Sharif Ali, to become her third sultan.

As customary for close affiliation and alliances in Southeast Asia, the royal family of Luzon intermarried with the ruling houses of the Sultanate of Brunei.[46] Intermarriage was a common strategy for Southeast Asian states to extend their influence.[47] However, Islamic Brunei's power was not uncontested in Borneo since it had a Hindu rival in a state founded by Indians called Kutai in the south which they overpowered but didn't destroy.

Nevertheless, by the 16th century, Islam was firmly rooted in Brunei, and the country had built one of its biggest mosques. In 1578, Alonso Beltrán, a Spanish traveller, described it as being five stories tall and built on the water.[48]

War with Spain and decline

Brunei briefly rose to prominence in Southeast Asia when the Portuguese occupied Malacca and thereby forced the wealthy and powerful but displaced Muslim refugees there to relocate to nearby Sultanates such as Brunei. The Bruneian Sultan then intervened in a territorial conflict between Hindu Tondo and Muslim Manila in the Philippines by appointing the Bruneian descended Rajah Ache of Manila as admiral of the Bruneian navy in a rivalry against Tondo and as the enforcer of Bruneian interests in the Philippines. He subsequently encountered the Magellan expedition[49] wherein Antonio Pigafetta noted that under orders from his grandfather the Sultan of Brunei, Ache had previously sacked the Buddhist city of Loue in Southwest Borneo for being faithful to the old religion and rebelling against the authority of Sultanate.[50] However, European influence gradually brought an end to Brunei's regional power, as Brunei entered a period of decline compounded by internal strife over royal succession. In the face of these invasions by European Christian powers, the Ottoman Caliphate aided the beleaguered Southeast Asian Sultanates by making Aceh a protectorate and sending expeditions to reinforce, train and equip the local mujahideen.[51] Turks were routinely migrating to Brunei as evidenced by the complaints of Manila Oidor Melchor Davalos who in his 1585 report, say that Turks were coming to Sumatra, Borneo and Ternate every year, including defeated veterans from the Battle of Lepanto.[52]

Spain declared war in 1578, planning to attack and capture Kota Batu, Brunei's capital at the time. This was based in part on the assistance of two Bruneian noblemen, Pengiran Seri Lela and Pengiran Seri Ratna. The former had travelled to Manila, then the centre of the Spanish colony. Manila itself was captured from Brunei, Christianised and made a territory of the Viceroyalty of New Spain which was centered in Mexico City. Pengiran Seri Lela came to offer Brunei as a tributary to Spain for help to recover the throne usurped by his brother, Saiful Rijal.[53] The Spanish agreed that if they succeeded in conquering Brunei, Pengiran Seri Lela would be appointed as the sultan, while Pengiran Seri Ratna would be the new Bendahara.

In March 1578, a fresh Spanish fleet had arrived from Mexico and settled at the Philippines. They were led by De Sande, acting as Capitán-General. He organized an expedition from Manila for Brunei, consisting of 400 Spaniards and Mexicans, 1,500 Filipino natives, and 300 Borneans.[54] The campaign was one of many, which also included action in Mindanao and Sulu.[55][56] The racial make-up of the Christian side was diverse since it were usually made up of Mestizos, Mulattoes and Amerindians (Aztecs, Mayans and Incans) who were gathered and sent from Mexico and were led by Spanish officers who had worked together with native Filipinos in military campaigns across the Southeast Asia.[57] The Muslim side was also equally racially diverse. In addition to the native Malay warriors, the Ottomans had repeatedly sent military expeditions to nearby Aceh. The expeditions were composed mainly of Turks, Egyptians, Swahilis, Somalis, Sindhis, Gujaratis and Malabars.[58] These expeditionary forces had also spread to other nearby Sultanates such as Brunei and had taught new fighting tactics and techniques on how to forge cannons.[59]

Eventually, the Spanish captured the capital on 16 April 1578, with the help of Pengiran Seri Lela and Pengiran Seri Ratna. The Sultan Saiful Rijal and Paduka Seri Begawan Sultan Abdul Kahar were forced to flee to Meragang then to Jerudong. In Jerudong, they made plans to chase the conquering army away from Brunei. Suffering high fatalities due to a cholera or dysentery outbreak,[60][61] the Spanish decided to abandon Brunei and returned to Manila on 26 June 1578, after 72 days.[62]

Pengiran Seri Lela died in August or September 1578, probably from the same illness suffered by his Spanish allies.[citation needed] There was suspicion that the legitimist sultan could have been poisoned by the ruling sultan.[citation needed] Seri Lela's daughter, a Bruneian princess, "Putri", had left with the Spanish, she abandoned her claim to the crown and then she married a Christian Tagalog, named Agustín de Legazpi de Tondo.[63] Agustin de Legaspi along with his family and associates were soon implicated in the Conspiracy of the Maharlikas, an attempt by Filipinos to link up with the Brunei Sultanate and Japanese Shogunate to expel the Spaniards from the Philippines.[64] However, upon the Spanish suppression of the conspiracy, the Bruneian descended aristocracy of precolonial Manila were exiled to Guerrero, Mexico which consequently later became a center of the Mexican war of independence against Spain.[65][66]

The local Brunei accounts[67] of the Castilian War differ greatly from the generally accepted view of events. What was called the Castilian War was seen as a heroic episode, with the Spaniards being driven out by Bendahara Sakam, purportedly a brother of the ruling sultan, and a thousand native warriors. Most historians consider this to be a folk-hero account, which probably developed decades or centuries after.[68]

Brunei eventually descended into anarchy. The country suffered a civil war from 1660 to 1673.

British intervention

The British have intervened in the affairs of Brunei on several occasions. Britain attacked Brunei in July 1846 due to internal conflicts over who was the rightful Sultan.[69]

In the 1880s, the decline of the Bruneian Empire continued. The sultan granted land (now Sarawak) to James Brooke, who had helped him quell a rebellion, and allowed him to establish the Raj of Sarawak. Over time, Brooke and his nephews (who succeeded him) leased or annexed more land. Brunei lost much of its territory to him and his dynasty, known as the White Rajahs.

Sultan Hashim Jalilul Alam Aqamaddin appealed to the British to stop further encroachment by the Brookes.[70] The "Treaty of Protection" was negotiated by Sir Hugh Low and signed into effect on 17 September 1888. The treaty said that the sultan "could not cede or lease any territory to foreign powers without British consent"; it provided Britain effective control over Brunei's external affairs, making it a British protected state (which continued until 1984).[71][72] But, when the Raj of Sarawak annexed Brunei's Pandaruan District in 1890,[73] the British did not take any action to stop it. They did not regard either Brunei or the Raj of Sarawak as 'foreign' (per the Treaty of Protection). This final annexation by Sarawak left Brunei with its current small land mass and separation into two parts.[74]

British residents were introduced in Brunei under the Supplementary Protectorate Agreement in 1906.[75][76] The residents were to advise the sultan on all matters of administration. Over time, the resident assumed more executive control than the sultan. The residential system ended in 1959.[77]

Discovery of oil

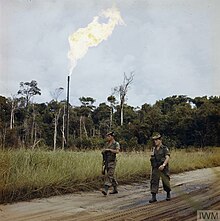

Petroleum was discovered in 1929 after several fruitless attempts.[78] Two men, F. F. Marriot and T. G. Cochrane, smelled oil near the Seria river in late 1926.[79] They informed a geophysicist, who conducted a survey there. In 1927, gas seepages were reported in the area. Seria Well Number One (S-1) was drilled on 12 July 1928. Oil was struck at 297 metres (974 ft) on 5 April 1929. Seria Well Number 2 was drilled on 19 August 1929, and, as of 2009[update], continues to produce oil.[80] Oil production was increased considerably in the 1930s with the development of more oil fields. In 1940, oil production was at more than six million barrels.[80] The British Malayan Petroleum Company (now Brunei Shell Petroleum Company) was formed on 22 July 1922.[81] The first offshore well was drilled in 1957.[82] Oil and natural gas have been the basis of Brunei's development and wealth since the late 20th century.

Japanese occupation

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

The Japanese invaded Brunei on 16 December 1941, eight days after their attack on Pearl Harbor and the United States Navy. They landed 10,000 troops of the Kawaguchi Detachment from Cam Ranh Bay at Kuala Belait. After six days' fighting, they occupied the entire country. The only Allied troops in the area were the 2nd Battalion of the 15th Punjab Regiment based at Kuching, Sarawak.[83]

Once the Japanese occupied Brunei, they made an agreement with Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin over governing the country. Inche Ibrahim (known later as Pehin Datu Perdana Menteri Dato Laila Utama Awang Haji Ibrahim), a former Secretary to the British Resident, Ernest Edgar Pengilly, was appointed chief administrative officer under the Japanese Governor. The Japanese had proposed that Pengilly retain his position under their administration, but he declined. Both he and other British nationals still in Brunei were interned by the Japanese at Batu Lintang camp in Sarawak. While the British officials were under Japanese guard, Ibrahim made a point of personally shaking each one by the hand and wishing him well.[84][85]

The Sultan retained his throne and was given a pension and honours by the Japanese. During the later part of the occupation, he resided at Tantuya, Limbang and had little to do with the Japanese. Most of the Malay government officers were retained by the Japanese. Brunei's administration was reorganised into five prefectures, which included British North Borneo. The Prefectures included Baram, Labuan, Lawas, and Limbang. Ibrahim hid numerous significant government documents from the Japanese during the occupation. Pengiran Yusuf (later YAM Pengiran Setia Negara Pengiran Haji Mohd Yusuf), along with other Bruneians, was sent to Japan for training. Although in the area the day of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Yusuf survived.

The British had anticipated a Japanese attack, but lacked the resources to defend the area because of their engagement in the war in Europe. The troops from the Punjab Regiment filled in the Seria oilfield oilwells with concrete in September 1941 to deny the Japanese their use. The remaining equipment and installations were destroyed when the Japanese invaded Malaya. By the end of the war, 16 wells at Miri and Seria had been restarted, with production reaching about half the pre-war level. Coal production at Muara was also recommenced, but with little success.

During the occupation, the Japanese had their language taught in schools, and Government officers were required to learn Japanese. The local currency was replaced by what was to become known as duit pisang (banana money). From 1943 hyper-inflation destroyed the currency's value and, at the end of the war, this currency was worthless. Allied attacks on shipping eventually caused trade to cease. Food and medicine fell into short supply, and the population suffered from famine and disease.

The airport runway was constructed by the Japanese during the occupation, and in 1943 Japanese naval units were based in Brunei Bay and Labuan. The naval base was destroyed by Allied bombing, but the airport runway survived. The facility was developed as a public airport. In 1944 the Allies began a bombing campaign against the occupying Japanese, which destroyed much of the town and Kuala Belait, but missed Kampong Ayer.[86]

On 10 June 1945, the Australian 9th Division landed at Muara under Operation Oboe Six to recapture Borneo from the Japanese. They were supported by American air and naval units. Brunei town was bombed extensively and recaptured after three days of heavy fighting. Many buildings were destroyed, including the Mosque. The Japanese forces in Brunei, Borneo, and Sarawak, under Lieutenant-General Masao Baba, formally surrendered at Labuan on 10 September 1945. The British Military Administration took over from the Japanese and remained until July 1946.

Post-World War II

After World War II, a new government was formed in Brunei under the British Military Administration (BMA). It consisted mainly of Australian officers and servicemen.[87] The administration of Brunei was passed to the Civil Administration on 6 July 1945. The Brunei State Council was also revived that year.[88] The BMA was tasked to revive the Bruneian economy, which was extensively damaged by the Japanese during their occupation. They also had to put out the fires on the wells of Seria, which had been set by the Japanese prior to their defeat.[88]

Before 1941, the Governor of the Straits Settlements, based in Singapore, was responsible for the duties of British High Commissioner for Brunei, Sarawak, and North Borneo (now Sabah).[89] The first British High Commissioner for Brunei was the Governor of Sarawak, Sir Charles Ardon Clarke. The Barisan Pemuda ("Youth Front"; abbreviated as BARIP) was the first political party to be formed in Brunei, on 12 April 1946. The party intended to "preserve the sovereignty of the Sultan and the country, and to defend the rights of the Malays".[90] BARIP also contributed to the composition of the country's national anthem. The party was dissolved in 1948 due to inactivity.

In 1959, a new constitution was written declaring Brunei a self-governing state, while its foreign affairs, security, and defence remained the responsibility of the United Kingdom.[91] A small rebellion erupted against the monarchy in 1962, which was suppressed with help of the UK.[92] Known as the Brunei Revolt, the rebellion contributed to the Sultan's decision to opt out of joining the emerging state now called Malaysia under the umbrella of North Borneo Federation.[91]

Brunei gained its independence from the United Kingdom on 1 January 1984.[91] The official National Day, which celebrates the country's independence, is held by tradition on 23 February.[93]

Writing of the Constitution

In July 1953, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III formed a seven-member committee named Tujuh Serangkai, to determine the citizens' views regarding a written constitution for Brunei. In May 1954, the Sultan, Resident and High Commissioner met to discuss the findings of the committee. They agreed to authorise the drafting of a constitution. In March 1959, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III led a delegation to London to discuss the proposed Constitution.[94] The British delegation was led by Sir Alan Lennox-Boyd, Secretary of State for the Colonies. The British Government later accepted the draft constitution.

On 29 September 1959, the Constitution Agreement was signed in Brunei Town. The agreement was signed by Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III and Sir Robert Scott, the Commissioner-General for Southeast Asia. It included the following provisions:[75]

- The Sultan was made the Supreme Head of State.

- Brunei was responsible for its internal administration.

- The British Government was responsible for foreign and defence affairs only.

- The post of Resident was abolished and replaced by a British High Commissioner.

Five councils were established:[95]

- The Executive Council

- The Legislative Council of Brunei

- The Privy Council

- The Council of Succession

- The State Religious Council

National development plans

A series of National Development Plans was initiated by the 28th Sultan of Brunei, Omar Ali Saifuddien III.

The first was introduced in 1953.[96] A total sum of B$100 million was approved by the Brunei State Council for the plan. E.R. Bevington, from the Colonial Office in Fiji, was appointed to implement it.[97] A US$14 million Gas Plant was built under the plan. In 1954, survey and exploration work were undertaken by the Brunei Shell Petroleum on both offshore and onshore fields. By 1956, production reached 114,700 bpd.

The plan also aided the development of public education. By 1958, expenditure on education totalled at $4 million.[97] Communications were improved, as new roads were built and reconstruction at Berakas Airport was completed in 1954.[98]

The second National Development Plan was launched in 1962.[98] A major oil and gas field was discovered in 1963. Developments in the oil and gas sector have continued, and oil production has steadily increased since then.[99] The plan also promoted the production of meat and eggs for consumption by citizens. The fishing industry increased its output by 25% throughout the course of the plan. The deepwater port at Muara was also constructed during this period. Power requirements were met, and studies were made to provide electricity to rural areas.[99] Efforts were made to eradicate malaria, an endemic disease in the region, with the help of the World Health Organization. Malaria cases were reduced from 300 cases in 1953 to only 66 cases in 1959.[100] The death rate was reduced from 20 per thousand in 1947 to 11.3 per thousand in 1953.[100] Infectious disease has been prevented by public sanitation and improvement of drainage, and the provision of piped pure water to the population.[100]

Independence

On 14 November 1971, Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah left for London to discuss matters regarding the amendments to the 1959 constitution. A new agreement was signed on 23 November 1971 with the British representative being Anthony Royle.[101]

Under this agreement, the following terms were agreed upon:

- Brunei was granted full internal self-government

- The UK would still be responsible for external affairs and defence.

- Brunei and the UK agreed to share the responsibility for security and defence.

This agreement also caused Gurkha units to be deployed in Brunei, where they remain up to this day.

On 7 January 1979, another treaty was signed between Brunei and the United Kingdom. It was signed with Lord Goronwy-Roberts being the representative of the UK. This agreement granted Brunei to take over international responsibilities as an independent nation. Britain agreed to assist Brunei in diplomatic matters. In May 1983, it was announced by the UK that the date of independence of Brunei would be 1 January 1984.[102]

On 31 December 1983, a mass gathering was held on main mosques on all four of the districts of the country and at midnight, on 1 January 1984, the Proclamation of Independence was read by Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah. The sultan subsequently assumed the title "His Majesty", rather than the previous "His Royal Highness".[103] Brunei was admitted to the United Nations on 22 September 1984, becoming the organisation's 159th member.[104]

21st century

In October 2013, Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah announced his intention to impose Penal Code from Sharia on the country's Muslims, which make up roughly two thirds of the country's population.[105] This would be implemented in three phases, culminating in 2016, and making Brunei the first and only country in East Asia to introduce Sharia into its penal code, excluding the subnational Indonesian special territory of Aceh.[106] The move attracted international criticism,[107] the United Nations expressing "deep concern".[108]

Geography

Brunei is a southeast Asian country consisting of two unconnected parts with a total area of 5,765 square kilometres (2,226 sq mi) on the island of Borneo. It has 161 kilometres (100 mi) of coastline next to the South China Sea, and it shares a 381 km (237 mi) border with Malaysia. It has 500 square kilometres (193 sq mi) of territorial waters, and a 200-nautical-mile (370 km; 230 mi) exclusive economic zone.[71]

About 97% of the population lives in the larger western part (Belait, Tutong, and Brunei-Muara), while only about 10,000 people live in the mountainous eastern part (Temburong District). The total population of Brunei is approximately 408,000 as of July 2010[update], of which around 150,000 live in the capital Bandar Seri Begawan.[109] Other major towns are the port town of Muara, the oil-producing town of Seria and its neighbouring town, Kuala Belait. In Belait District, the Panaga area is home to large numbers of Europeans expatriates, due to Royal Dutch Shell and British Army housing, and several recreational facilities are located there.[110]

Most of Brunei is within the Borneo lowland rain forests ecoregion, which covers most of the island. Areas of mountain rain forests are located inland.[111] In Brunei forest cover is around 72% of the total land area, equivalent to 380,000 hectares (ha) of forest in 2020, down from 413,000 hectares (ha) in 1990. In 2020, naturally regenerating forest covered 374,740 hectares (ha) and planted forest covered 5,260 hectares (ha). Of the naturally regenerating forest 69% was reported to be primary forest (consisting of native tree species with no clearly visible indications of human activity) and around 5% of the forest area was found within protected areas. For the year 2015, 100% of the forest area was reported to be under public ownership.[112][113]

The climate of Brunei is tropical equatorial that is a tropical rainforest climate[71] more subject to the Intertropical Convergence Zone than the trade winds and with no or rare cyclones. Brunei is exposed to the risks stemming from climate change along with other ASEAN member states.[114][115]

Politics and government

Brunei's political system is governed by the constitution and the national tradition of the Malay Islamic Monarchy (Melayu Islam Beraja; MIB). The three components of MIB cover Malay culture, Islamic religion, and the political framework under the monarchy.[116] It has a legal system based on English common law, although Islamic law (sharia) supersedes this in some cases.[71] Brunei has a parliament but there are no elections; the last election was held in 1962.[117]

Under Brunei's 1959 constitution, the Sultan, currently Hassanal Bolkiah, is the head of state with full executive authority. Following the Brunei Revolt of 1962, this authority has included emergency powers, which are renewed every two years, meaning that Brunei has technically been under martial law since then.[91] Hassanal Bolkiah also serves as the state's prime minister, finance minister and defence minister.[118]

Foreign relations

Until 1979, Brunei's foreign relations were managed by the UK government. After that, they were handled by the Brunei Diplomatic Service. After independence in 1984, this Service was upgraded to ministerial level and is now known as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[119]

Officially, Brunei's foreign policy is as follows:[120]

- Mutual respect of others' territorial sovereignty, integrity and independence;

- The maintenance of friendly relations among nations;

- Non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries; and

- The maintenance and the promotion of peace, security and stability in the region.

With its traditional ties with the United Kingdom, Brunei became the 49th member of the Commonwealth immediately on the day of its independence on 1 January 1984.[121] As one of its first initiatives toward improved regional relations, Brunei joined ASEAN on 7 January 1984, becoming the sixth member. To achieve recognition of its sovereignty and independence, it joined the United Nations as a full member on 21 September of that same year.[122]

As an Islamic country, Brunei became a full member of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (now the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation) in January 1984 at the Fourth Islamic Summit held in Morocco.[123]

After its accession to the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum (APEC) in 1989, Brunei hosted the APEC Economic Leaders' Meeting in November 2000 and the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) in July 2002.[124] Brunei became a founding member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) on 1 January 1995,[125] and is a major player in BIMP-EAGA, which was formed during the Inaugural Ministers' Meeting in Davao, Philippines, on 24 March 1994.[126]

Brunei shares a close relationship with Singapore and the Philippines. In April 2009, Brunei and the Philippines signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) that seeks to strengthen the bilateral co-operation of the two countries in the fields of agriculture and farm-related trade and investments.[127]

Brunei is one of many nations to lay claim to some of the disputed Spratly Islands.[128] The status of Limbang as part of Sarawak has been disputed by Brunei since the area was first annexed in 1890.[128] The issue was reportedly settled in 2009, with Brunei agreeing to accept the border in exchange for Malaysia giving up claims to oil fields in Bruneian waters.[129] The Brunei government denies this and says that their claim on Limbang was never dropped.[130][131]

Brunei was the chair for ASEAN in 2013.[132] It also hosted the ASEAN summit on that same year.[133]

Military

Brunei maintains three infantry battalions stationed around the country.[91] The Brunei navy has several "Ijtihad"-class patrol boats purchased from a German manufacturer. The United Kingdom also maintains a base in Seria, the centre of the oil industry in Brunei. A Gurkha battalion consisting of 1,500 personnel is stationed there.[91] United Kingdom military personnel are stationed there under a defence agreement signed between the two countries.[91]

A Bell 212 operated by the air force crashed in Kuala Belait on 20 July 2012 with the loss of 12 of the 14 crew on board. The cause of the accident has yet to be ascertained.[134] The crash is the worst aviation incident in the history of Brunei.

The Army is currently acquiring new equipment,[135] including UAVs and S-70i Black Hawks.[136]

Brunei's Legislative Council proposed an increase of the defence budget for the 2016–17 fiscal year of about five per cent to 564 million Brunei dollars ($408 million). This amounts to about ten per cent of the state's total national yearly expenditure and represents around 2.5 per cent of GDP.[137]

Administrative divisions

Brunei is divided into four districts (daerah), namely Brunei-Muara, Belait, Tutong and Temburong. Brunei-Muara District is the smallest yet the most populous, and home to the country's capital Bandar Seri Begawan. Belait is the birthplace and centre for the country's oil and gas industry. Temburong is an exclave and separated from the rest of the country by the Brunei Bay and Malaysian state of Sarawak. Tutong is home to Tasek Merimbun, the country's largest natural lake.

Each district is divided into several mukims. Altogether there are 39 mukims in Brunei. Each mukim encompasses several villages (kampung or kampong).

Bandar Seri Begawan and towns in the country (except Muara and Bangar) are administered as Municipal Board areas (kawasan Lembaga Bandaran). Each municipal area may constitute villages or mukims, partially or as a whole. Bandar Seri Begawan and a few of the towns also function as capitals of the districts where they are located.

A district and its constituent mukims and villages are administered by a District Office (Jabatan Daerah). Meanwhile, municipal areas are governed by Municipal Departments (Jabatan Bandaran). Both District Offices and Municipal Departments are government departments under the Ministry of Home Affairs.

Legal system

Brunei has numerous courts in its judicial branch. The highest court, though subject in civil cases to the appellate jurisdiction of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council,[138] is the Supreme Court, which consists of the Court of Appeal and High Court. Both of these have a chief justice and two judges.[71]

Women and children

The U.S. Department of State has stated that discrimination against women is a problem in Brunei.[139] The law prohibits sexual harassment and stipulates that whoever assaults or uses criminal force, intending thereby to outrage or knowing it is likely to outrage the modesty of a person, shall be punished with imprisonment for as much as five years and caning. The law stipulates imprisonment of up to 30 years, and caning with not fewer than 12 strokes for rape. The law does not criminalise spousal rape; it explicitly states that sexual intercourse by a man with his wife, as long as she is not under 13 years of age, is not rape. Protections against sexual assault by a spouse are provided under the amended Islamic Family Law Order 2010 and Married Women Act Order 2010. The penalty for breaching a protection order is a fine not exceeding BN$2,000 or imprisonment not exceeding six months. By law, sexual intercourse with a female under 14 years of age constitutes rape and is punishable by imprisonment for not less than eight years and not more than 30 years and not less than 12 strokes of the cane. The intent of the law is to protect girls from exploitation through prostitution and "other immoral purposes", including pornography.[139]

Bruneian citizenship is derived through parents' nationality rather than jus soli. Parents with stateless status are required to apply for a special pass for a child born in the country. Failure to register a child may make it difficult to enroll the child in school.

LGBT rights

Male and female homosexuality is illegal in Brunei. Sexual relations between men are punishable by death or whipping; sex between women is punishable by caning or imprisonment.

In May 2019, the Brunei government extended its existing moratorium on the death penalty to the Sharia criminal code as well that made homosexual acts punishable with death by stoning.[140]

In 2019, Brunei announced that it would no longer be implementing the second phase of its controversial sharia penal code. The code, which was first introduced in 2014, included a range of punishments for crimes such as theft, drug offences, and same-sex relationships, including amputation and death by stoning.

The decision to halt the implementation of the second phase of the code came after significant international backlash and pressure from countries and human rights organizations, who criticized the harsh punishments as inhumane and a violation of human rights.

The government of Brunei stated that the decision was made in order to maintain peace and stability in the country, and to avoid any negative impact on the economy and reputation of the country. The Sultan of Brunei, Hassanal Bolkiah, also issued a statement saying that the country would continue to "strengthen and improve" its legal system in line with international norms and best practices.

It is worth mentioning that the first phase of the sharia penal code, which includes fines and imprisonment for offenses such as failure to attend Friday prayers and consuming alcohol, remains in place.

Religious rights

In The Laws of Brunei, the right of non-Muslims to practice their faith is guaranteed by the 1959 Constitution. However, celebrations and prayers must be confined to places of worship and private residences.[141] Upon adopting Sharia Penal Code, the Ministry of Religious Affairs banned Christmas decorations in public places, but did not forbid celebration of Christmas in places of worship and private premises.[142] On 25 December 2015, 4,000 out of 18,000 estimated local Catholics attended the mass of Christmas Day and Christmas Eve.[141] In 2015, the then-head of the Catholic Church in Brunei told The Brunei Times, "To be quite honest there has been no change for us this year; no new restrictions have been laid down, although we fully respect and adhere to the existing regulations that our celebrations and worship be [confined] to the compounds of the church and private residences".[141]

Brunei's revised penal code came into force in phases, commencing on 22 April 2014 with offences punishable by fines or imprisonment.[143][144] The complete code, due for final implementation later,[when?] stipulated the death penalty for numerous offenses (both violent and non-violent), such as insult or defamation of Muhammad, insulting any verses of the Quran and Hadith, blasphemy, declaring oneself a prophet or non-Muslim, robbery, rape, adultery, sodomy, extramarital sexual relations for Muslims, and murder. Stoning to death was the specified "method of execution for crimes of a sexual nature". Rupert Colville, spokesperson for the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) declared that, "Application of the death penalty for such a broad range of offences contravenes international law."[145]

Animal rights

Brunei is the first country in Asia to have banned shark finning nationwide.[146]

Brunei has retained most of its forests, compared to its neighbours that share Borneo island. There is a public campaign calling to protect pangolins which are considered a threatened treasure in Brunei.[147]

Economy

Brunei has the second-highest Human Development Index among the Southeast Asian nations, after Singapore.[148][149] Crude oil and natural gas production account for about 90% of its GDP.[91] About 167,000 barrels (26,600 m3) of oil are produced every day, making Brunei the fourth-largest producer of oil in Southeast Asia.[91] It also produces approximately 25.3 million cubic metres (890 million cubic feet) of liquified natural gas per day, making Brunei the ninth-largest gas exporter in the world.[91] Forbes also ranks Brunei as the fifth-richest nation out of 182, based on its petroleum and natural gas fields.[150] Brunei was ranked 88th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[151]

Substantial income from overseas investment supplements income from domestic production. Most of these investments are made by the Brunei Investment Agency, an arm of the Ministry of Finance.[91] The government provides for all medical services,[152] and subsidises rice[153] and housing.[91]

The national air carrier, Royal Brunei Airlines, is trying to develop Brunei as a hub for international travel between Europe and Australia/New Zealand. Central to this strategy is the position that the airline maintains at London Heathrow Airport. It holds a daily slot at the highly capacity-controlled airport, which it serves from Bandar Seri Begawan via Dubai. The airline also has services to major Asian destinations including Hong Kong, Bangkok, Singapore and Manila.

Brunei depends heavily on imports such as agricultural products (e.g. rice, food products, livestock, etc.),[154] vehicles and electrical products from other countries.[155] Brunei imports 60% of its food; of that amount, around 75% come from other ASEAN countries.[154]

Brunei's leaders are concerned that increasing integration in the world economy will undermine internal social cohesion and have therefore pursued an isolationist policy. However, it has become a more prominent player by serving as chairman for the 2000 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum. Brunei's leaders plan to upgrade the labour force, reduce unemployment, which was at 6.9% in 2014;[156] strengthen the banking and tourism sectors, and, in general, broaden the economic base.[157] A long-term development plan aims to diversify growth.[158]

The government of Brunei has also promoted food self-sufficiency, especially in rice. Brunei renamed its Brunei Darussalam Rice 1 as Laila Rice during the launch of the "Padi Planting Towards Achieving Self-Sufficiency of Rice Production in Brunei Darussalam" ceremony at the Wasan padi fields in April 2009.[159] In August 2009, the Royal Family reaped the first few Laila padi stalks, after years of attempts to boost local rice production, a goal first articulated about half a century ago.[160] In July 2009 Brunei launched its national halal branding scheme, Brunei Halal, with a goal to export to foreign markets.[161]

In 2020, Brunei's electricity production was largely based on fossil fuels; renewable energy accounted for less than 1% of produced electricity in the country.[162]

Infrastructure

As of 2019, the country's road network constituted a total length of 3,713.57 kilometres (2,307.51 mi), out of which 86.8% were paved.[163] The 135-kilometre (84 mi) highway from Muara Town to Kuala Belait is a dual carriageway.[116]

Brunei is accessible by air, sea, and land transport. Brunei International Airport is the main entry point to the country. Royal Brunei Airlines[164] is the national carrier. There is another airfield, the Anduki Airfield, located in Seria. The ferry terminal at Muara services regular connections to Labuan (Malaysia). Speedboats provide passenger and goods transportation to the Temburong district.[165] The main highway running across Brunei is the Tutong-Muara Highway. The country's road network is well developed. Brunei has one main sea port located at Muara.[91]

The airport in Brunei is currently being extensively upgraded.[166] Changi Airport International is the consultant working on this modernisation, which planned cost is currently $150 million.[167][168] This project is slated to add 14,000 square metres (150,000 sq ft) of new floorspace and includes a new terminal and arrival hall.[169] With the completion of this project, the annual passenger capacity of the airport is expected to double from 1.5 to 3 million.[167]

With one private car for every 2.09 persons, Brunei has one of the highest car ownership rates in the world. This has been attributed to the absence of a comprehensive transport system, low import tax, and low unleaded petrol price of B$0.53 per litre.[116]

A new 30-kilometre (19 mi) roadway connecting the Muara and Temburong districts of opened to traffic on March 17, 2020.[170] Fourteen kilometres (9 mi) of this roadway would be crossing the Brunei Bay.[171] The bridge cost is $1.6 billion.[172]

Banking

Bank of China received permission to open a branch in Brunei in April 2016. Citibank, which entered in 1972, closed its operations in Brunei in 2014. HSBC, which had entered in 1947, closed its operation in Brunei in November 2017.[173] Maybank of Malaysia, RHB Bank of Malaysia, Standard Chartered Bank of United Kingdom, United Overseas Bank of Singapore and Bank of China are currently operating in Brunei.

Demographics

Ethnicities indigenous to Brunei include the Belait, Brunei Bisaya (not to be confused with the Bisaya/Visaya of the nearby Philippines), indigenous Bruneian Malay, Dusun, Kedayan, Lun Bawang, Murut and Tutong.

The population of Brunei in 2021 was 445,373,[174][175] of which 76% live in urban areas. The rate of urbanisation is estimated at 2.13% per year from 2010 to 2015. The average life expectancy is 77.7 years.[176] In 2014, 65.7% of the population were Malay, 10.3% are Chinese, 3.4% are indigenous, with 20.6% smaller groups making up the rest.[177] There is a relatively large expatriate community.[178] Most expats come from non-Muslim countries such as Australia, United Kingdom, South Korea, Japan, The Philippines, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam and India.

Religion

Religion in Brunei (2021)[6]

Islam is the official religion of Brunei,[71] specifically that of the Sunni denomination and the Shafi'i school of Islamic jurisprudence. More than 82% of the population, including the majority of Bruneian Malays and Kedayans identify as Muslim. Other faiths practised are Christianity (6.7%) Buddhism (6.3%, mainly by the Chinese).[6] Freethinkers, mostly Chinese, form about 2% of the population. Although most of them practise some form of religion with elements of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism, they prefer to present themselves as having practised no religion officially, hence labelled as atheists in official censuses. Followers of indigenous religions are about 2% of the population.[179]

Languages

The official language of Brunei is Standard Malay, for which both the Latin alphabet (Rumi) and the Arabic alphabet (Jawi) are used.[180] Initially, Malay was written in the Jawi script before it switched to the Latin alphabet around 1941.[181]

The principal spoken language is Melayu Brunei (Brunei Malay). Brunei Malay is rather divergent from standard Malay and the rest of the Malay dialects, being about 84% cognate with standard Malay,[182] and is mostly mutually intelligible with it.[183]

English is widely used as a business and official language and it is spoken by a majority of the population in Brunei. English is used in business as a working language and as the language of instruction from primary to tertiary education.[184][185][186][187]

Chinese languages are also widely spoken, and the Chinese minority in Brunei speaks a number of varieties of Chinese.

Arabic is the religious language of Muslims and is taught in schools, particularly religious schools, and also in institutes of higher learning. As of 2004, there are six Arabic schools and one religious teachers' college in Brunei. A majority of Brunei's Muslim population has had some form of formal or informal education in the reading, writing and pronunciation of the Arabic language as part of their religious education.

Other languages and dialects spoken include Kedayan Malay dialect, Tutong Malay dialect, Murut, and Dusun.[182]

Culture

The culture of Brunei is predominantly Malay (reflecting its ethnicity), with heavy influences from Islam, but is seen as much more conservative than Indonesia and Malaysia.[188] Influences to Bruneian culture come from the Malay cultures of the Malay Archipelago. Four periods of cultural influence have occurred: animist, Hindu, Islamic, and Western. Islam had a very strong influence, and was adopted as Brunei's ideology and philosophy.[189]

As a Sharia country, the sale and public consumption of alcohol is banned.[190] Non-Muslims are allowed to bring in a limited amount of alcohol from their point of embarkation overseas for their own private consumption.[116]

Media

Media in Brunei are said to be pro-government; press criticism of the government and monarchy is rare. The country ranks "Not Free" in media by Freedom House.[191] Nonetheless, the press is not overtly hostile toward alternative viewpoints and is not restricted to publishing only articles regarding the government. The government allowed a printing and publishing company, Brunei Press PLC, to form in 1953. The company continues to print the English daily Borneo Bulletin. This paper began as a weekly community paper and became a daily in 1990[116] Apart from The Borneo Bulletin, there is also the Media Permata and Pelita Brunei, the local Malay newspapers which are circulated daily. The Brunei Times is another English independent newspaper published in Brunei since 2006.[192]

The Brunei government, through state broadcaster Radio Television Brunei (RTB), owns and operates three television channels with the introduction of digital TV using DVB-T (RTB Perdana, RTB Aneka and RTB Sukmaindera) and five radio stations (National FM, Pilihan FM, Nur Islam FM, Harmony FM and Pelangi FM). A private company has made cable television available (Astro-Kristal) as well as one private radio station, Kristal FM.[116] It also has an online campus radio station, UBD FM, that streams from its first university, Universiti Brunei Darussalam.[193]

Sport

The most popular sport in Brunei is association football. The Brunei national football team joined FIFA in 1969, but has not had much success. Brunei's top football league is the Brunei Super League, which is managed by the Football Association of Brunei Darussalam (FABD). The nation has its own martial arts called "Silat Suffian Bela Diri".[194]

Brunei debuted at the Olympics in 1996 and has competed at all subsequent Summer Olympics except the 2008 edition. The country has competed in badminton, shooting, swimming, and track-and-field, but has yet to win any medals. The Brunei Darussalam National Olympic Council is the National Olympic Committee for Brunei.

Brunei has had slightly more success at the Asian Games, winning four bronze medals. The first major international sporting event to be hosted in Brunei was the 1999 Southeast Asian Games. According to the all-time Southeast Asian Games medal table, Bruneian athletes have won a total of 14 gold, 55 silver and 163 bronze medals at the games.

See also

Notes

- ^ There is a Legislative Council, which has no legislative power.[7] As its role is only consultative it is not considered to be a legislature.[8][9]

- ^ /bruːˈnaɪ/ broo-NY, Malay: [brunaɪ]

- ^ In Malay, the official name of Brunei is Negara Brunei Darussalam, literal meaning "Nation of Brunei, the Abode of Peace". However, in English, the official name of the country is always written as Brunei Darussalam.[15][16]

- ^ Malay: Negara Brunei Darussalam Jawi: نݢارا بروني دارالسلام, lit. 'State of Brunei, the Abode of Peace'[17]

References

- ^ Deterding, David; Athirah, Ishamina (22 July 2016). "Brunei Malay". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 47. Cambridge University Press: 99–108. doi:10.1017/S0025100316000189. ISSN 0025-1003. S2CID 201819132. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ "Brunei". Ethnologue. 19 February 1999. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ McLellan, J., Noor Azam Haji-Othman, & Deterding, D. (2016). The Language Situation in Brunei Darussalam. In Noor Azam Haji-Othman., J. McLellan & D. Deterding (Eds.), The use and status of language in Brunei Darussalam: A kingdom of unexpected linguistic diversity (pp. 9–16). Singapore: Springer.

- ^ "Call to add ethnic languages as optional subject in schools". Archived from the original on 19 November 2013. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ Writing contest promotes usage, history of Jawi script Archived 12 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. The Brunei Times (22 October 2010)

- ^ a b c d "Population by Religion, Sex and Census Year". Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ "Brunei Darussalam" (PDF). United Nations (Human Rights Council): 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "Brunei: Freedom in the World 2020 Country Report". Freedom House. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "Brunei". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "Brunei-Muara District" (PDF). Information.gov.bn (2nd ed.). Information Department, Prime Minister's Office, Brunei Darussalam. 2010. p. 8. ISBN 978-99917-49-24-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Population". Department of Economic Planning and Development. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Brunei)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Archived from the original on 1 November 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/2024" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "Delegation Record for .BN". IANA. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ "Home - gov.bn". Archived from the original on 4 September 2018.

- ^ "Embassy of Brunei Darussalam to the United States of America". Brunei Embassy. Archived from the original on 6 December 2000.

- ^ Peter Haggett (ed). Encyclopedia of World Geography, Volume 1, Marshall Cavendish, 2001, p. 2913.

- ^ Abinales, Patricio N. and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines. Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2005.

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 26.

- ^ de Vienne 2016, p. 27.

- ^ "Treasuring Brunei's past". Southeast Asian Archaeology. 8 March 2007. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ Robert Nicholl (1980). Notes on Some Controversial Issues in Brunei History. pp. 32–37.

- ^ James B. Minahan (2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-59884-660-7.

- ^ "Geographical Names Database". United Nations Statistics Division. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ "Brunei Darussalam". asean.org. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ "Brunei Darussalam". The Commonwealth. 15 August 2013. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Bilcher Bala (2005). Thalassocracy: a history of the medieval Sultanate of Brunei Darussalam. School of Social Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah. ISBN 978-983-2643-74-6.

- ^ Tsang, Cheng-hwa (2000), "Recent advances in the Iron Age archaeology of Taiwan", Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 20: 153–158, doi:10.7152/bippa.v20i0.11751

- ^ Turton, M. (2021). Notes from central Taiwan: Our brother to the south. Taiwan's relations with the Philippines date back millennia, so it's a mystery that it's not the jewel in the crown of the New Southbound Policy. Taiwan Times.

- ^ Everington, K. (2017). Birthplace of Austronesians is Taiwan, capital was Taitung: Scholar. Taiwan News.

- ^ Bellwood, P., H. Hung, H., Lizuka, Y. (2011). Taiwan Jade in the Philippines: 3,000 Years of Trade and Long-distance Interaction. Semantic Scholar.

- ^ Wendy Hutton (2000). Adventure Guides: East Malaysia. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 31–57. ISBN 978-962-593-180-7. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Brunei Rediscovered: A Survey of Early Times By Robert Nicholl p. 35 citing Ferrand. Relations, page 564-65. Tibbets, Arabic Texts, pg 47.

- ^ Brunei Rediscovered: A Survey of Early Times By Robert Nicholl Archived 20 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine p. 35 citing Ferrand. Relations, page 564–65. Tibbets, Arabic Texts, pg 47.

- ^ Wendy Hutton (2000). Adventure Guides: East Malaysia. Tuttle Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-962-593-180-7.

- ^ Coedes, Indianized States, Page 128, 132.

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 43.

- ^ Journal of Southeast Asian Studies Vol. 14, No. 1 (Mar., 1983) Page 40. Published by: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Reading Song-Ming Records on the Pre-colonial History of the Philippines Archived 13 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine By Wang Zhenping Page 256.

- ^ Quanzhou to the Sulu Zone and beyond: Questions Related to the Early Fourteenth Century Archived 3 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine By: Roderich Ptak. Page 280

- ^ "Naskah Nagarakretagama" (in Indonesian). Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ Ming shi, 325, p. 8411, p. 8422.

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 44.

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 45.

- ^ Church, Peter (2017). A Short History of South-East Asia. John Wiley & Sons. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-119-06249-3.

- ^ Junker, Laura Lee (1998). "Integrating History and Archaeology in the Study of Contact Period Philippine Chiefdoms". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 2 (4): 291–320. doi:10.1023/A:1022611908759. S2CID 141415414.

- ^ Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 978-971-550-135-4.

- ^ Nicholl 2002, pp. 47–51

- ^ de Aganduru Moriz, Rodrigo (1882). Historia general de las Islas Occidentales a la Asia adyacentes, llamadas Philipinas. Colección de Documentos inéditos para la historia de España, v.78–79. Madrid: Impr. de Miguel Ginesta.

- ^ Tom Harrisson, Brunei's Two (or More) Capitals, Brunei Museum Journal, Vol. 3, No. 4 (1976), p. 77 sq.

- ^ Kayadibi, Saim. "Ottoman Connections to the Malay World: Islam, Law and Society", (Kuala Lumpur: The Other Press, 2011)

- ^ Melchor Davalos to the King, Manila 20 June 1585, in Lewis Hanke, Cuerpo de Documentos del Siglo XVI sobre los derechos de España en las Indias y las Filipinas (Mexico 1977), pp 72, 75.

- ^ Melo Alip 1964, pp. 201, 317

- ^ United States War Dept 1903, p. 379

- ^ McAmis 2002, p. 33

- ^ "Letter from Francisco de Sande to Felipe II, 1578". filipiniana.net. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ Letter from Fajardo to Felipe III From Manila, August 15 1620. (From the Spanish Archives of the Indies) Archived 4 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine("The infantry does not amount to two hundred men, in three companies. If these men were that number, and Spaniards, it would not be so bad; but, although I have not seen them, because they have not yet arrived here, I am told that they are, as at other times, for the most part boys, mestizos, and mulattoes, with some Indians (Native Americans). There is no little cause for regret in the great sums that reënforcements of such men waste for, and cost, your Majesty. I cannot see what betterment there will be until your Majesty shall provide it, since I do not think, that more can be done in Nueva Spaña, although the viceroy must be endeavoring to do so, as he is ordered.")

- ^ Tarling, Nicholas (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia by Nicholas Tarling p. 39. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521663700. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ Cambridge illustrated atlas, warfare: Renaissance to revolution, 1492–1792 by Jeremy Black p. 16 [1] Archived 1 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Frankham 2008, p. 278

- ^ Atiyah 2002, p. 71

- ^ Saunders 2002, pp. 54–60

- ^ Saunders 2002, p. 57

- ^ Martinez, Manuel F. Assassinations & conspiracies : from Rajah Humabon to Imelda Marcos. Manila: Anvil Publishing, 2002.

- ^ "Estado de Guerrero Historia" [State of Guerrero History]. Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. 2005. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "La Riqueza Histórica de Guerrero" [The Historical Richness of Guerrero] (in Spanish). Guerrero, Mexico: Government of Guerrero. Archived from the original on 3 November 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 41.

- ^ Saunders 2002, pp. 57–58

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 52.

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f "Brunei". CIA World Factbook. 2011. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ Hussainmiya, B. A. (2006). "Appendix 3: British-Brunei (Protectorate) Treaty, 17 September 1888". Brunei Revival of 1906: A Popular History Archived 7 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine (PDF). Bandar Seri Begawan: Brunei Press Sdn Bhd. p. 77. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ "Translation: From His Highness the Sultan Hashim of Brunei- To A. Keyser, Esq. H. M. Consul for Brunei, 22 Zulkaidah 1316". Cession of the Limbang territory to Sarawak. Forwards letter, from the Sultan of Brunei, regarding- (Archival File). High Commissioner Office, Malaya. 1 March 1899. pp. 6–10. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2022 – via Arkib Negara Malaysia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 58.

- ^ a b History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 59.

- ^ Hussainmiya, B. A. (2006). "Appendix 4: British-Brunei (Protectorate) Document, 3 December 1905 and 2 January 1906: (Supplementary) Agreement between His Majesty's Government and the Sultan of Brunei Providing for More Effectual British Protection over the State of Brunei". Brunei Revival of 1906: A Popular History (PDF). Bandar Seri Begawan: Brunei Press Sdn Bhd. p. 77. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 September 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

His Highness will receive a British Officer, to be styled Resident, and will provide a suitable residence for him. The Resident will be the Agent and Representative of His Britannic Majesty's Government under the High Commissioner for the British Protectorates in Borneo, and his advice must be taken and acted upon on all questions in Brunei

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 67.

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 12.

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 13.

- ^ a b History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 14.

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Berry, Rob (2008). Macmillan Atlas. Macmillan Education Australia. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4202-0995-2.

- ^ "Brunei under the Japanese occupation", Rozan Yunos, Brunei Times, Bandar Seri Begawan, 29 June 2008

- ^ Hussainmiya, B. A. (2003). "Resuscitating Nationalism : Brunei under the Japanese Military Administration (1941-1945)". Senri Ethnological Studies. 65. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ "The Japanese Interregnum...," Graham Saunders, A history of Brunei, Edition 2, illustrated, reprint, Routledge, 2002, p. 129, ISBN 070071698X, 978-0700716982

- ^ "Japanese occupation", Historical Dictionary of Brunei Darussalam, Jatswan S. Sidhu, Edition 2, illustrated, Scarecrow Press, 2009, p. 115, ISBN 0810870789, 978-0810870789

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 79.

- ^ a b History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 80.

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 81.

- ^ A History of Brunei (2002). A History of Brunei. Routledge. p. 131. ISBN 0-7007-1698-X. Archived from the original on 25 April 2024. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Background Note: Brunei". US Department of State. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ Pocock, Tom (1973). Fighting General – The Public &Private Campaigns of General Sir Walter Walker (First ed.). London: Collins. ISBN 0-00-211295-7.

- ^ "Brunei National Day". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 98.

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 100.

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 92.

- ^ a b History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 129.

- ^ a b History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 21.

- ^ a b History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 96.

- ^ a b c A History of Brunei (2002). A History of Brunei. Routledge. p. 130. ISBN 0-7007-1698-X. Archived from the original on 25 April 2024. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- ^ Ministry of Education, Brunei (2008). "The Nation Building Years 150–1984". History for Brunei Darussalam. EBP Pan Pacific. p. 101. ISBN 978-9991725451.

- ^ Ministry of Education, Brunei (2008). "The Nation Building Years 150–1984". History for Brunei Darussalam. EBP Pan Pacific. p. 102. ISBN 978-9991725451.

- ^ "Reminiscing Brunei's independence proclamation". Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 21 March 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ Brunei is Greeted as the 159th U.N. Member Archived 30 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times

- ^ "Brunei's sultan to implement Sharia penal code". USA Today. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "The Implications of Brunei's Sharia Law". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ McNew, David (7 May 2014). "Brunei's Sharia law creates backlash in Beverly Hills". MSNBC. Archived from the original on 30 December 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ "Brunei introduces tough Islamic penal code". BBC News. 30 April 2014. Archived from the original on 26 May 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ 2001 Summary Tables of the Population Census. Department of Statistics, Brunei Darussalam

- ^ "Outpost Seria". Outpost Seria Housing Information. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ "Brunei Darussalam Country Profile". UK Foreign & Commonwealth Office. Archived from the original on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ Terms and Definitions FRA 2025 Forest Resources Assessment, Working Paper 194. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2023.

- ^ "Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020, Brunei Darussalam". Food Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- ^ Indra Overland (2017). "Impact of Climate Change on ASEAN International Affairs: Risk and Opportunity Multiplier". Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) and Myanmar Institute of International and Strategic Studies (MISIS). Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Overland, Indra; Sagbakken, Haakon Fossum; Chan, Hoy-Yen; Merdekawati, Monika; Suryadi, Beni; Utama, Nuki Agya; Vakulchuk, Roman (December 2021). "The ASEAN climate and energy paradox". Energy and Climate Change. 2: 100019. doi:10.1016/j.egycc.2020.100019. hdl:11250/2734506.

- ^ a b c d e f "About Brunei". Bruneipress.com.bn. 30 July 1998. Archived from the original on 23 June 2002. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ "Brunei Darussalam : Constitution and politics". thecommonwealth.org. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ PMO Organisation Chart. "Organisation Chart at the Prime Minister's Office". Archived from the original on 22 December 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ "About Us". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ Ministry of Education (2008). History for Brunei Darussalam. EBP Pan Pacific. p. 104. ISBN 978-9991725451.

- ^ "MOFAT, Commonwealth". Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade of Brunei Darussalam. 30 March 2010. Archived from the original on 28 January 2010.

- ^ "MOFAT, UN". Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade of Brunei Darussalam. 30 March 2010. Archived from the original on 18 February 2008.

- ^ "MOFAT, OIC". Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade of Brunei Darussalam. 30 March 2010. Archived from the original on 18 June 2008.

- ^ "APEC, 2000 Leaders' Declaration". Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation. 30 March 2010. Archived from the original on 21 March 2010.

- ^ "MOFAT, WTO". Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 30 March 2010. Archived from the original on 25 June 2008.

- ^ "MOFAT, BIMP-EAGA". Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 30 March 2010. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008.

- ^ Marvyn N. Benaning (29 April 2009) RP, "Brunei seal agri cooperation deal"[dead link], Manila Bulletin

- ^ a b "Disputes – International". CIA. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- ^ "Brunei drops all claims to Limbang". Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Azlan Othman. "Brunei Denies Limbang Story". Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ "Brunei Denies Limbang Story". MySinchew. 19 March 2009. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ State Department, United States. "Brunei's ASEAN Chairmanship Scorecard". cogitASIA CSIS Asia Policy Blog. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Rano Iskandar. "Brunei to host ASEAN Summit 2013". Archived from the original on 30 April 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ "12 killed in Brunei helicopter crash". CNN. 21 July 2012. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ "RBAF stages large-scale exercise using new military equipment, vehicles". Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Black Hawks expected to arrive in 2014". Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Maierbrugger, Arno (12 March 2016). "Brunei defense budget to be raised by 5% | Investvine". Investvine. Archived from the original on 21 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Court, The Supreme. "Role of the JCPC - Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC)". www.jcpc.uk. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ a b 2010 Human Rights Report: Brunei Darussalam Archived 25 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine. US Department of State

- ^ Oppenheim, Maya (5 May 2019). "Brunei says it will not enforce death penalty for gay sex in dramatic U-turn". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ a b c The Brunei Times Archived 31 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Minister: Brunei unfairly hurt by unverified news on Christmas ban". 26 December 2015. Archived from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ "30.04.14 Implementation of the Shari'ah Penal Code Order, 2013". 30 April 2014. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ "Brunei announces implementation of Sharia law". Deutsche Welle. 30 April 2014. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ UN concerned at broad application of death penalty in Brunei's revised penal code, 11 April 2014, archived from the original on 7 August 2015, retrieved 5 August 2015

- ^ "Brunei Institutes Asia's First Nationwide Shark Fin Ban". WildAid. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ Hii, Robert (3 October 2015). "Saving Pangolins From Extinction: Brunei". Huffpost. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ Nations, United. "Human Development Reports". United Nations. Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2020: Brunei Darussalam" (PDF). 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Forbes ranks Brunei fifth richest nation". 25 February 2012. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012.

- ^ World Intellectual Property Organization (2024). "Global Innovation Index 2024: Unlocking the Promise of Social Entrepreneurship". www.wipo.int. p. 18. doi:10.34667/tind.50062. ISBN 978-92-805-3681-2. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Brunei Healthcare Info. "Brunei Healthcare". Archived from the original on 30 December 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ Bandar Seri Begawan (16 May 2008). "Subsidy on rice, sugar to stay". Brunei Times via Chinese Embassy. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ a b "Department of Agriculture, Brunei Darussalam". Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ Brunei Statistical Year Book (PDF). Brunei Government. 2010. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2012.

- ^ "Brunei unemployment rate in 2014 at 6.9%". The Brunei Times. 1 July 2015. Archived from the original on 21 June 2016.

- ^ "Sultanate Moves to reduce unemployment". BruDirect. 14 December 2011. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ "Report by Brunei Darussalam", Trade Policy Review: Brunei Darussalam 2015, Trade Policy Reviews, WTO, 21 May 2015, pp. 81–93, doi:10.30875/048d8871-en, ISBN 978-92-870-4182-1

- ^ Ubaidillah Masli, Goh De No and Faez Hani Brunei-Muapa (28 April 2009). "'Laila Rice' to Brunei's rescue". Bt.com.bn. Archived from the original on 16 January 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ Ubaidillah Masli, Deno Goh and Faez Hani Brunei-Muapa (4 August 2009). "HM inaugurates Laila harvest". Bt.com.bn. Archived from the original on 16 January 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ Hadi Dp Mahmud (1 August 2009). "Brunei pioneers national halal branding". Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 2 August 2009. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ "Brunei Darussalam: How to Build an Investment Climate for Renewable Energy?". Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ BRUNEI DARUSSALAM STATISTICAL YEARBOOK 2019 (PDF). Department of Economic Planning and Statistics. 2020. ISBN 9789991772264. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ^ "Welcome to Royal Brunei Airlines". Bruneiair. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- ^ "Speedboat services to and from Temburong". Borneo Bulletin. 3 September 2009. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.