Columbus Railway, Power & Light office

| Columbus Railway, Power & Light office | |

|---|---|

The building, vacant, in 2021 | |

| |

| General information | |

| Status | Vacant |

| Type | Railway office |

| Address | 842 Cleveland Avenue, Columbus, Ohio |

| Coordinates | 39°58′52″N 82°59′21″W / 39.981116°N 82.989274°W |

| Completed | 1890s |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 2 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Yost & Packard[1] |

The former Columbus Railway, Power & Light office is a historic building in the Milo-Grogan neighborhood of Columbus, Ohio. The two-story brick structure was designed by Yost & Packard and built in the 1890s as a transportation company office. The property was part of a complex of buildings, including a power plant, streetcar barn, and inspection shop. The office building, the only remaining portion of the property, was utilized as a transit office into the 1980s, and has remained vacant since then. Amid deterioration and lack of redevelopment, the site has been on Columbus Landmarks' list of endangered sites since 2014.

The office building is, along with the Milo Arts complex, one of the two most important historic structures in Milo-Grogan. The city's department of development recommended its listing on the Columbus Register of Historic Properties. Its preservation is also a top priority for neighborhood leaders.

Attributes

[edit]

The Columbus Railway, Power & Light office is located at the southern entrance to the Milo-Grogan neighborhood, at the northeast corner of Cleveland and Reynolds Avenues.[2] The building was designed by prominent architects Yost & Packard.[1]

The relatively small brick building has two stories and a steep hipped roof. It has a rectangular footprint and rows of windows along its two full floors; the first-floor windows are trabeated; the second-floor windows are round-arched. The building also includes a tall octagonal tower at its southwest corner, featuring a third, round, set of windows. It is topped with an eight-sided flared roof. Below the tower roof and much of the main roof is a brick arcaded corbel table. The eastern section of the building is slightly shorter than the rest; lacking the decorative corbel table.[3]

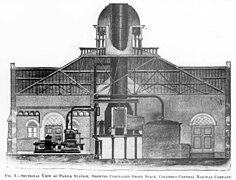

The building was part of a complex of a power plant and streetcar barn (the Columbus Central Street Railway Car Depot and Power House) during its operation; those buildings have since been demolished.[2][4] The power house, built in 1894, was a large building of cut stone, brick, and terra cotta, measuring 100 by 100 ft. The building had a pyramidal roof with large dormers on each side and a flat skylight in the center, surrounded by a balustrade, and with a central ornamental cupola.[5] The building was also designed by architects Yost & Packard.[6][7] The building was noted as a unique take away from the norm of power plants at the time; this structure was designed to hide its industrial uses, including its large smokestack.[5]

The site's carhouse and inspection shop were adjoining structures at the southeast corner of Cleveland and Reynolds Avenues. The carhouse was the largest of five in the streetcar system, and about a third of the streetcar staff were employed there in 1918.[8] It measured 88 by 360 ft., and was made of brick with a steel roof and concrete floor.[9]

History

[edit]The office building was built in the 1890s[2] for the Columbus Central Railway Company, which operated the Columbus & Westerville Railway (incorporated in 1891 and completed in 1895). The transit company became the Columbus Railway, Power & Light Co. in 1914.[2] The office remained in Columbus Railway Power & Light operation until 1937, when it was sold to the Columbus & Southern Ohio Electric Co. It became operated by the Columbus Transit Co. by 1949,[10] and was purchased by the transit company in 1958.[11]

A 1930 fire demolished part of the property's 1894 car barn, prompting a reconstruction within the following weeks.[12] The rail line serving the complex ceased service in December 1929, and was officially abandoned on October 13, 1931.[13]

In January 1974, the Central Ohio Transit Authority (COTA) began operation, soon after purchasing the Columbus Transit Company. On the first day of service, the agency board and management team met at the Milo-Grogan office, then known as the Cleveland Ave. Transportation Office. The team greeted employees and handed out "first-run" pins to mark the inaugural operation of COTA lines.[14]

In 1976, COTA purchased the property; it had been leasing it from the defunct transit company since 1974. The site included the bus storage facility, maintenance facility, and operational building, which COTA together purchased for $651,700.[15] COTA operated the facility through at least 1979;[16] COTA planned to replace the bus storage and maintenance facility with a new building that year.[17] In 1987, the agency agreed to sell the 5-acre property.[18] It sold to HVW Inc. that year.[11]

In 1993, Herbert L. Williams purchased the building, transferred to Viola Williams in 1994.[19][11] By 2000, the building fell into disrepair, marred with graffiti and tall weeds, and multiple broken windows with rusted bars across them. An artist, Nicole Tschampel, attempted to purchase the building in a June 2000 sheriff's sale, to create an art studio with apartments above. Despite Tschampel's winning bid of $25,500 ($3,000 of which was owed back taxes), local realtor Carl H. Woodford found the owner, paid the taxes, and put the building on sale for $80,000 before the deed could be transferred.[19] In 2014, Woodford's real estate license was revoked after the Ohio Department of Commerce investigated a similar action he took; Woodford has collected hundreds of thousands of dollars from former property owners through similar scams, revealed by The Columbus Dispatch in 2019.[20] Carl Woodford still owns the building. It has long been vacant and has never been restored; in 2017, Woodford disclosed that he has "private plans" in the works.[4][21]

Preservation

[edit]The former railway building is, along with the Milo Arts building, one of the two most important historic structures in Milo-Grogan. It is a top priority for preservation for neighborhood leaders. The 2007 Milo-Grogan Neighborhood Plan recommended listing on the Columbus Register of Historic Properties in order to preserve the site, and to look into placing it on the National Register of Historic Places as well.[22] In 1897, The Columbus Dispatch called the property's buildings the "largest and handsomest" in Milo, even following completion of the now-historic Milo Public Elementary School.[23]

The site was listed on Columbus Landmarks' 2014, 2015, and 2016 "Most Endangered" sites lists.[24] The office building remains on the organization's list of endangered sites.[25]

Gallery

[edit]-

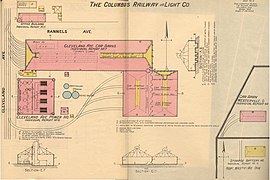

Map of the site in 1899

-

1909 map

-

1918 map

-

Cutaway diagram of the powerhouse, 1895

-

Powerhouse interior, 1895

-

The complex housing COTA buses in 1978

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Classified List Of Public and Private Structures, by Yost & Packard" (PDF). Portfolio of Architectural Realities. 1897. OCLC 81808814. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 4, 2022. Retrieved August 18, 2023 – via Grandview Heights/Marble Cliff Historical Society.

- ^ a b c d Dunham, Tom (2010). Columbus's Industrial Communities: Olentangy, Milo-Grogan, Steelton. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4520-5970-9. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ Samuelson, Robert E.; et al. (Pasquale C. Grado, Judith L. Kitchen, Jeffrey T. Darbee) (1976). Architecture: Columbus. The Foundation of The Columbus Chapter of The American Institute of Architects. pp. 262–3. OCLC 2697928.

- ^ a b "Columbus Railway Power & Light". Columbus Landmarks. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ a b "Electrical Review 1894-08-01: Vol 25 Iss 5". August 1894.

- ^ "Electric Power House". The Columbus Dispatch. July 21, 1894. p. 7. Retrieved May 28, 2021. Columbus Metropolitan Library access

- ^ "Columbus Central". The Columbus Dispatch. November 22, 1894. p. 8. Retrieved May 28, 2021. Columbus Metropolitan Library access

- ^ "Columbus Inspection Rebuilt as Unit, and Track Layout Improved" (PDF). Electric Railway Journal. May 18, 1918.

- ^ "Novel Powerhouse Construction in Columbus, O." (PDF). The Street Railway Journal. February 1985.

- ^ "Urge Bus Riders To Get Refund Slips". The Columbus Dispatch. November 22, 1949. p. 1. Retrieved May 22, 2021. Columbus Metropolitan Library access

- ^ a b c "Franklin County Auditor Assessment List". Franklin County Auditor. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ "Milo Car Barn To Be Reconstructed". The Columbus Dispatch. August 23, 1930. p. 3. Retrieved May 28, 2021. Columbus Metropolitan Library access

- ^ "The Villager" (PDF). Minerva Park Community Association. March 1998. p. 4. Archived from the original (.pdf) on 8 October 2021.

- ^ "COTA Readies Takeover". The Columbus Dispatch. December 30, 1973. p. 12A. Retrieved May 22, 2021. Columbus Metropolitan Library access

- ^ Switzer, John (April 1, 1976). "COTA Trustees OK Purchase of 2 Sites". The Columbus Dispatch. p. A-4. Retrieved May 22, 2021. Columbus Metropolitan Library access

- ^ Daft, Betty (August 5, 1979). "Milo-Grogan". The Columbus Dispatch. p. 42. Retrieved May 22, 2021. Columbus Metropolitan Library access

- ^ Ruth, Robert (June 3, 1979). "Voters To Decide COTA Tax Issue". The Columbus Dispatch. p. 8-6. Retrieved May 22, 2021. Columbus Metropolitan Library access

- ^ Kubera, Rosemary (July 30, 1987). "COTA Still Needs A Downtown Office". The Columbus Dispatch. p. 9D. Retrieved May 22, 2021. Columbus Metropolitan Library access

- ^ a b Carmen, Barbara (August 15, 2000). "Buyers Beware: Pitfalls Lurking At Sheriff's Sale". The Columbus Dispatch. p. 01B. Retrieved May 22, 2021. Columbus Metropolitan Library access

- ^ Jim Weiker; John Futty; Julie Fulton (August 11, 2019). "Foreclosed and Fleeced". The Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ Ball, Brian. "History: Central Ohio's railroad relics". Columbus Monthly. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ "Milo-Grogan Neighborhood Plan". City of Columbus Department of Development. 2007. pp. 12, 23. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ "Milo Annexation". The Columbus Dispatch. March 8, 1897. p. 10. Retrieved May 22, 2021. Columbus Metropolitan Library access

- ^ "2021 Most Endangered Sites – Columbus Landmarks". Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ "2021 Atlas of Columbus Landmarks". Columbus Landmarks. 2021. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

External links

[edit]