National Cancer Institute

| |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 5, 1937 |

| Jurisdiction | Federal government of the United States |

| Headquarters | Office of the Director, 31 Center Drive, Building 31, Bethesda, Maryland, 20814 |

| Agency executive |

|

| Parent department | United States Department of Health and Human Services |

| Parent agency | National Institutes of Health |

| Child agencies |

|

| Website | www |

| Footnotes | |

| [1][2][3][4][5] | |

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) coordinates the United States National Cancer Program and is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which is one of eleven agencies that are part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The NCI conducts and supports research, training, health information dissemination, and other activities related to the causes, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer; the supportive care of cancer patients and their families; and cancer survivorship.[6]

NCI is the oldest and has the largest budget and research program of the 27 institutes and centers of the NIH ($6.9 billion in 2020).[7] It fulfills the majority of its mission via an extramural program that provides grants for cancer research. Additionally, the National Cancer Institute has intramural research programs in Bethesda, Maryland, and at the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research[8] at Fort Detrick in Frederick, Maryland. The NCI receives more than US$5 billion in funding each year.[9]

The NCI supports a nationwide network of 72 NCI-designated Cancer Centers with a dedicated focus on cancer research and treatment[10] and maintains the National Clinical Trials Network.[11]

History

[edit]Timeline

[edit]

- August 5, 1937: President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed into law the National Cancer Institute Act (Pub. Law 75-244; 50 Stat. 559), which established the National Cancer Institute, as a division of the Public Health Service.[12][13][14][15]

- 1940: The first issue of the Journal of the National Cancer Institute was published.

- 1944: The United States Congress made the NCI an operating division of the National Institutes of Health by its passage of the Public Health Service Act. Congress later amended the Public Health Service Act with the National Cancer Act of 1971, to broaden the scope and responsibilities of the NCI "in order more effectively to carry out the national effort against cancer."

- 1955: NCI established the Clinical Trials Cooperative Group Program, which included several research networks that conducted cancer clinical research primarily under the sponsorship of NCI.

- 1957: The first cancer, choriocarcinoma, was cured with chemotherapy at NCI.

- 1960: NCI began funding government-supported cancer centers.

- 1971: President Richard Nixon converted the U.S. Army's former biological warfare facilities at Fort Detrick, Maryland, to house research activities on the causes, treatment, and prevention of cancer.

- 1971: The National Cancer Act of 1971 declares "war on cancer," establishes the National Cancer Advisory Board, and allots additional funding for cancer research.

- 1975: The Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research opened in Frederick, Maryland, as a Federally Funded Research and Development Center

- 1993: The NIH Revitalization Act of 1993 encourages NCI to expand its efforts in prostate cancer, breast and other cancers which primarily or solely affected women, and authorized increased appropriations.

- 1998: Establishes the Office of Cancer Complementary and Alternative Medicine to study pseudoscientific alternative medicine treatments for cancer

- 2009: The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 provided US$10 billion in additional funding for the NIH; the NCI received US$1.3 billion from that amount.

- 2016: The 21st Century Cures Act increased funding for biomedical research. The "Cancer Moonshot" program promised additional support for cancer research.[16]

- On October 17, 2017, Norman Sharpless was sworn in as the 15th director of the National Cancer Institute. In April 2019, Sharpless left NCI to serve as the acting Commissioner of Food and Drugs.[17] He returned to the institute in November 2019 as director.[18]

Anti-cancer drug investigations

[edit]

- Chlorambucil (Leukeran) (1957)

- Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) (1959)

- Thiotepa (1959)

- Melphalan (Alkeran) (1959) (IV in 1993)

- Streptozotocin (Zanosar) (1982)

- Ifosfamide (Ifex) (1988)

- Mercaptopurine (1953)

- Methotrexate (1953)

- Thioguanine (1966)

- Cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C) (1969)

- Floxuridine (FUDR) (1970)

- Fludarabine phosphate (1991)

- Pentostatin (1991)

- Chlorodeoxyadenosine (1992)

- Vincristine (Oncovin) (1963)

- Actinomycin D (Cosmegen) (1964)

- Mithramycin (Mithracin) (1970)

- Bleomycin (Blenoxane) (1973)

- Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) (1974)

- Mitomycin C (Mutamycin) (1974)

- L-Asparaginase (Elspar) (1978)

- Daunomycin (Cerubidine) (1979)

- VP-16-213 (Etoposide) (1983)

- VM-26 (Teniposide) (1992)

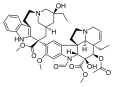

- Taxol (Paclitaxel) (1992)

Plant flavonoids

- chrysin quercetin galangin naringenin (1994)

- Hydroxyurea (Hydrea) (1967)

- Procarbazine (Matulane) (1969)

- O, P'-DDD (Lysodren, Mitotane) (1970)

- Dacarbazine (DTIC) (1975)

- CCNU (Lomustine) (1976)

- BCNU (Carmustine) (1977)

- Cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (Cisplatin) (1978)

- Mitoxantrone (Novantrone) (1988)

- Carboplatin (Paraplatin) (1989)

- Levamisole (Ergamisol) (1990)

- Hexamethylmelamine (Hexalen) (1990)

- All-trans retinoid acid (Vesanoid) (1995)

- Porfimer sodium (Photofrin) (1995)

- DES (1950)

- Prednisone (1953)

- Fluoxymesterone (Halotestin) (1958)

- Dromostanolone (Drolban) (1961)

- Testolactone (Teslac) (1970)

- Methyl prednisolone

- Prednisolone

- Zoladex (1989)

Biologicals

- Alpha interferon (Intron A, Roferon-A) (1986)

- BCG (TheraCys, TICE) (1990)

- G-CSF (1991)

- GM-CSF (1991)

- Interleukin 2 (Proleukin) (1992)

Organization

[edit]The NCI is divided into several divisions and centers.[19]

Intramural

[edit]- The CCR includes approximately 250 internal NCI research groups in Frederick and Bethesda.[20]

- DCEG is made up of eight branches within the Trans-divisional Research Program.[21]

Extramural

[edit]- Division of Cancer Biology

- DCB oversees approximately 2000 grants per year in the areas of cancer cell biology; cancer immunology, hematology, and etiology; DNA and chromosome aberrations; structural biology and molecular applications; tumor biology and microenvironment; and tumor metastasis.[22] "Special Research Programs" falling under the aegis of the DCB include: Physical Sciences-Oncology Network, Cancer Systems Biology Consortium, Oncology Models Forum, Barrett's Esophagus Translational Research Network, New Approaches to Synthetic Lethality for Mutant KRAS-Dependent Cancers, Molecular and Cellular Characterization of Screen-Detected Lesions, Fusion Oncoproteins in Childhood Cancers, and Cancer Tissue Engineering Collaborative.[23]

- Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences

- Division of Cancer Prevention

- Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis

- DCTD supports eight research programs: The Biometric Research Program, The Cancer Diagnosis Program, The Cancer Imaging Program, The Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, The Developmental Therapeutics Program, The Radiation Research Program, The Translational Research Program, and The Office of Cancer Complementary and Alternative Medicine.[24]

- Division of Extramural Activities

- DEA processes and supports the thousands of grant applications NCI receives each year and compiles reports on the progress of research funded by the NCI's programs.[25]

Office of the director

[edit]- Center for Biomedical Informatics and Information Technology

- Center for Cancer Genomics

- CCG was created in 2011 and is responsible for management of The Cancer Genome Atlas and cancer genomics initiatives.

- Center for Cancer Training

- Center for Global Health

- Center for Strategic Scientific Initiatives

- In the 1990s, the Unconventional Innovation Program was created to integrate interdisciplinary technology research with biological applications. It was reorganized in 2004 as the CSSI.[26]

- Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities

- Center for Research Strategy

- Coordinating Center for Clinical Trials

- Technology Transfer Center

Programs

[edit]NCI-designated Cancer Centers

[edit]The NCI-designated Cancer Centers are one of the primary arms in the NCI's mission in supporting cancer research. There are currently 72 so-designated centers; 9 cancer centers, 56 comprehensive cancer centers, and 7 basic laboratory cancer centers. NCI supports these centers with grant funding in the form of P30 Cancer Center Support Grants to support shared research resources and interdisciplinary programs. Additionally, faculty at the cancer centers receive approximately 75% of the grant funding awarded by the NCI to individual investigators.[10][27]

The NCI cancer centers program was introduced in 1971 with 15 participating institutions.[28]

National Clinical Trials Network

[edit]The National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) was formed in 2014, from the Cooperative Group program to modernize the existing system to support precision medicine clinical trials. With precision medicine, many patients must be screened to determine eligibility for treatments in development.[citation needed]

Lead Academic Participating Sites (LAPS) were chosen at 30 academic institutions for their ability to conduct clinical trials and screen a large number of participants and awarded grants to support the infrastructure and administration required for clinical trials. Most LAPS grant recipients are also NCI-designated cancer centers.[11] NCTN also stores surgical tissue from patients in a nationwide network of tissue banks at various universities.[29]

Developmental Therapeutics Program

[edit]The NCI Development Therapeutics Program (DTP) provides services and resources to the academic and private-sector research communities worldwide to facilitate the discovery and development of new cancer therapeutic agents.[30]

Under the label "Discovery & Development Services" several services are offered, among them the NCI-60 human cancer cell line screen and the Molecular Target Program.[31]

In the Molecular Target Program thousands of molecular targets have been measured in the NCI panel of 60 human tumor cell lines. Measurements include protein levels, RNA measurements, mutation status and enzyme activity levels.[32]

NCI-60 Human Tumor Cell Lines Screen

[edit]The evolution of strategies at the NCI illustrates the changes in screening that have resulted from advances in cancer biology. The Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP) operates a tiered anti-cancer compound screening program with the goal of identifying novel chemical leads and biological mechanisms. The DTP screen is a three phase screen which includes: an initial screen which first involves a single dose cytotoxicity screen with the 60 cell line assay. Those passing certain thresholds are subjected to a 5 dose screen of the same 60 cell-line panel to determine a more detailed picture of the biological activity. A second phase screen establishes the maximum tolerable dosage and involves in vivo examination of tumor regression using the hollow fiber assay. The third phase of the study is the human tumor xenograft evaluation.

Active compounds are selected for testing based on several criteria: disease type specificity in the in vitro assay, unique structure, potency, and demonstration of a unique pattern of cellular cytotoxicity or cytostasis, indicating a unique mechanism of action or intracellular target.

A high correlation of cytotoxicity with compounds of known biological mechanism is often predictive of the drugs mechanism of action and thus a tool to aid in the drug development and testing. It also tells if there is any unique response of the drug which is not similar to any of the standard prototype compounds in the NCI database.

Leadership

[edit]| Portrait | Director | Tenure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Carl Voegtlin[33] | January 13, 1938 – July 31, 1943 | |

|

Roscoe Roy Spencer | August 1, 1943 – July 1, 1947 | |

|

Leonard Andrew Scheele | July 1, 1947 – April 6, 1948 | Served as the seventh Surgeon General of the United States from 1948 to 1956. |

|

John Roderick Heller | May 15, 1948 – July 1, 1960 | |

|

Kenneth Milo Endicott | July 1, 1960 – November 10, 1969 | |

|

Carl Gwin Baker | July 13, 1970 – May 5, 1972 | |

|

Frank Joseph Rauscher, Jr. | May 5, 1972 – November 1, 1976 | |

|

Arthur Canfield Upton | July 29, 1977 – December 31, 1980 | |

|

Vincent T. DeVita, Jr. | July 9, 1980 – September 1, 1988 | |

|

Samuel Broder | December 22, 1988 – April 1, 1995 | |

|

Richard D. Klausner | August 1, 1995 – September 30, 2001 | 11th Director, left to become President of the Case Institute of Health, Science, and Technology and later Executive Director of Global Health for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.[34] |

|

Andrew C. von Eschenbach | January 22, 2002 – June 10, 2006 | 12th Director, served from 2001 to 2006 before transitioning to a role as Commissioner of Food and Drugs.[35][36] |

|

John E. Niederhuber | September 15, 2006 – July 12, 2010 | 13th Director of the NCI, was nominated by President George W. Bush.[37] |

|

Harold Varmus | July 12, 2010 – March 31, 2015 | Co-winner of the Nobel Prize for studies of the genetic basis of cancer.[38] He was director of the National Institutes of Health from 1993 to 1999. |

|

Norman E. Sharpless | October 17, 2017 – April 30, 2022 | 15th Director of the NCI.[39][40] Transitioned to acting Commissioner of Food and Drugs in April 2019 and returned to NCI in November 2019.[41] |

|

Monica Bertagnolli | October 17, 2022 – November 9, 2023 | 16th Director of NCI. First woman to hold the position.[42] |

|

Kimryn Rathmell | December 18, 2023 – Present | 17th Director of NCI.[43] |

Notable NCI faculty

[edit]- Amy Berrington de González, senior investigator and radiation epidemiology branch chief.

- Kathryn Zoon, Principal Deputy Director, 2002 to 2004.

- Michael B. Sporn was the Chief of the Laboratory of Chemoprevention, 1978 to 1995.

- Tom Misteli, NIH Distinguished Investigator and Director of the NCI Center for Cancer Research

- Susan Gottesman

- Sankar Adhya

- Ira Pastan

- Elaine Jaffe

- Michael Gottesman

- Robert C. Gallo

- Rosandra N. Kaplan, head of the tumor microenvironment and metastasis branch

- Michael Potter

- Sandra Wolin

- Charles J. Sherr

- Louis M. Staudt

- Gordon Zubrod

- Steven Rosenberg

- Alfred Singer, Chief of the Experimental Immunology Branch of the National Cancer Institute

- Xiaohong Rose Yang, senior investigator.

- Douglas R. Lowy, Chief, Laboratory of Cellular Oncology; NCI Principal Deputy Director, initial development, characterization, and clinical testing of the preventive virus-like particle-based HPV vaccines.

Notable people

[edit]- Susan Shurin, senior adviser

- Sudhir Srivastava, chief scientist at Cancer Biomarkers Research Group of the Division of Cancer Prevention

- Catharine West and Barry Rosenstein, lead investigators for the Radio-Genomics Consortium (established 2009)

See also

[edit]- American Cancer Society Center

- caBIG, the Cancer BioInformatics Grid, a National Cancer Institute (USA) initiative to link cancer researchers and their data

- Cancer Information Service (CIS)

- European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)

- Journal of the National Cancer Institute

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- NCI-designated Cancer Center

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "Director's Page". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ "NCI Director Dr. Norman E. Sharpless—Director's Page—Leadership—About NCI". National Cancer Institute. 18 December 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ "Dr Norman Edward Sharpless, MD, NIH Enterprise Directory (NED)". NED.NIH.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ "Visitor Information". National Cancer Institute. 1980-01-01. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ NCI's Shady Grove Campus To Open In 2013. Vol. LXII. 2 April 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

The change is being made primarily due to the leases expiring at EPN, EPS and a few other buildings on Executive Blvd. The new buildings would house, in one facility, staff from those leased sites... NCI will continue to occupy floors 10 and 11 of Bldg. 31's A wing, as well as much of the 3rd floor, and the NCI director will remain in 31. There are also many staff members in lab buildings and the Clinical Center on campus and a large presence in Frederick at Ft. Detrick.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Aviles, Natalie B. (2024). An Ungovernable Foe: Science and Policy Innovation in the U.S. National Cancer Institute. Columbia University Press. doi:10.7312/avil19668. ISBN 978-0-231-19668-0.

- ^ Philippidis, Alex (2020-09-21). "Top 50 NIH-Funded Institutions of 2020". GEN - Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ^ "NCI-Frederick: NCI-Frederick Home Page". NCIfCrf.gov. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ "Funding Trends". National Cancer Institute. 2018-12-20.

- ^ a b "NCI-Designated Cancer Centers". National Cancer Institute. 5 April 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ^ a b "NCI's National Clinical Trials Network". National Cancer Institute. 2014-05-29.

- ^ "National Cancer Institute Act: Text of the Act of August 5, 1937, creating the National Cancer Institute and authorizing an appropriation therefor". JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 19 (2): 133–137. 1 August 1957. doi:10.1093/jnci/19.2.133. ISSN 0027-8874. PMID 13502712.

- ^ "Statutes at Large Volume 50 (1937) Table of Contents; VOL. 49 – VOL. 51". LegisWorks.org. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ "75th Congress Public Law 244" (PDF). LegisWorks.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ "Statute 50 Page 559" (PDF). LegisWorks.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ December 13, 2016—Important Events in NCI History—National Cancer Institute (NCI). 18 October 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Kaplan, Sheila (2019-03-12). "National Cancer Chief, Ned Sharpless, Named F.D.A.'s Acting Commissioner". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ^ Collins, Francis (November 1, 2019). "Statement on the return of Dr. Ned Sharpless as NCI Director". The NIH Director. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ "NCI Organization". National Cancer Institute. 1980-01-01.

- ^ "About CCR". 21 July 2014.

- ^ "DCEG Home". Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics – National Cancer Institute. 1980-01-01.

- ^ "DCB Research Portfolio". National Cancer Institute. 2016-08-08.

- ^ "Division of Cancer Biology". National Cancer Institute. 2016-08-08.

- ^ "About DCTD – DCTD". dctd.cancer.gov.

- ^ "About NCI Division of Extramural Activities". deainfo.nci.nih.gov.

- ^ "History – Center for Strategic Scientific Initiatives (CSSI)". cssi.cancer.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-09-29. Retrieved 2017-09-28.

- ^ "OCC Homepage – OCCWebApp 2.1.0". cancercenters.cancer.gov.

- ^ "History of the NCI Cancer Centers Program". National Cancer Institute. 2012-08-13.

- ^ "NCTN Biospecimen Banks". nctnbanks.cancer.gov. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ "Welcome to the Developmental Therapeutics Program". Developmental Therapeutics Program. National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "Discovery & Development Services". Developmental Therapeutics Program. National Cancer Institute. 26 August 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "Molecular Targets". Developmental Therapeutics Program. National Cancer Institute. 12 May 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ "National Cancer Institute (NCI)". 7 July 2015.

- ^ "Dr. Richard D. Klausner Named Executive Director of Global Health for Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation".

- ^ U.S. Congress (7 December 2006). "Executive Session". Congressional Record. 152 (134): S11404–29, S11447–51. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 109th Congress – 2nd Session". www.senate.gov.

- ^ "Emergent Biosolutions – Board of Directors bio". Retrieved 2013-12-06.

- ^ "Director's Page – National Cancer Institute (Archive)". Cancer.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-03-31. Retrieved 2015-04-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "NCI Director Dr. Norman E. Sharpless—Director's Page—Leadership—About NCI". National Cancer Institute. 18 December 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019. [verification needed]

- ^ "Dr Norman Edward Sharpless, MD, NIH Enterprise Directory (NED)". NED.NIH.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2019. [verification needed]

- ^ "NCI Director Dr. Norman E. Sharpless". National Cancer Institute. 2017-10-17. Retrieved 2020-02-12.

- ^ "Monica Bertagnolli becomes NCI director - NCI". www.cancer.gov. 2022-10-03. Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- ^ "W. Kimryn Rathmell begins work as 17th director of the National Cancer Institute". www.cancer.gov. 2023-12-18. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

General references

[edit]- National Cancer Institute Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- "NCI MISSION STATEMENT". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 18 August 2004.

- "THE NATIONAL CANCER ACT OF 1971". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 18 August 2004.

- Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP)

External links

[edit]- Official website

- NCI account on USAspending.gov

- NCI Dictionaries: NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms (utilizing non-technical language) • NCI Dictionary of Genetics Terms (for healthcare professionals) • NCI Drug Dictionary (includes links for potential clinical trials)

- NCI in A Short History of the National Institutes of Health, an online exhibit by the Office of NIH History

- Important Events in NCI History from the NIH Almanac

- Major NCI Milestones infographic