War on cancer

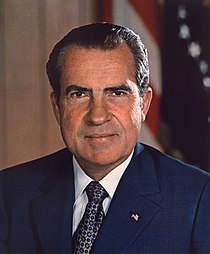

The "war on cancer" is the effort to find a cure for cancer by increased research to improve the understanding of cancer biology and the development of more effective cancer treatments, such as targeted drug therapies. The aim of such efforts is to eradicate cancer as a major cause of death. The signing of the National Cancer Act of 1971 by United States president Richard Nixon is generally viewed as the beginning of this effort, though it was not described as a "war" in the legislation itself.[1]

Despite significant progress in the treatment of certain forms of cancer (such as childhood leukemia[2]), cancer in general remains a major cause of death half a century after this war on cancer began,[3] leading to a perceived lack of progress[4][5][6] and to new legislation aimed at augmenting the original National Cancer Act of 1971.[7]

New research directions, in part based on the results of the Human Genome Project, hold promise for a better understanding of the genetic factors underlying cancer, and the development of new diagnostics, therapies, preventive measures, and early detection ability. However, targeting cancer proteins can be difficult, as a protein can be undruggable.

History

[edit]National Cancer Act of 1971

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

The war on cancer began with the National Cancer Act of 1971, a United States federal law.[9] The act was intended "to amend the Public Health Service Act so as to strengthen the National Cancer Institute in order to more effectively carry out the national effort against cancer".[1] It was signed into law by President Nixon on December 23, 1971.[10]

Health activist and philanthropist Mary Lasker was instrumental in persuading the United States Congress to pass the National Cancer Act.[11] She and her husband Albert Lasker were strong supporters of medical research. They established the Lasker Foundation which awarded people for their research. In the year of 1943, Mary Lasker began changing the American Cancer Society to get more funding for research. Five years later she contributed to getting federal funding for the National Cancer Institute and the National Heart Institute. In 1946 the funding was around $2.8 million and had grown to over $1.4 billion by 1972. In addition to all of these accomplishments, Mary became the president of the Lasker Foundation due to the death of her husband in 1952. Lasker's devotion to medical research and experience in the field eventually contributed to the passing of the National Cancer Act.[12]

The improved funding for cancer research has been quite beneficial over the last 40 years. In 1971, the number of survivors in the U.S. was 3 million and as of 2007 has increased to more than 12 million.[13]

NCI Director's Challenge

[edit]In 2003, Andrew von Eschenbach, the director of the National Cancer Institute (who served as FDA Commissioner from 2006 to 2009 and is now a Director at biotechnology company BioTime) issued a challenge "to eliminate the suffering and death from cancer, and to do so by 2015".[14][15] This was supported by the American Association for Cancer Research in 2005[16] though some scientists felt this goal was impossible to reach and undermined von Eschenbach's credibility.[17]

John E. Niederhuber, who succeeded Andrew von Eschenbach as NCI director, noted that cancer is a global health crisis, with 12.9 million new cases diagnosed in 2009 worldwide and that by 2030, this number could rise to 27 million including 17 million deaths "unless we take more pressing action".[18]

Harold Varmus, former director of the NIH and director of the NCI from 2010 to 2015,[19][20] held a town hall meeting in 2010[21] in which he outlined his priorities for improving the cancer research program, including the following:

- reforming the clinical trials system,

- improving utilization of the NIH clinical center (Mark O. Hatfield Clinical Research Center),

- readjusting the drug approval and regulation processes,

- improving cancer treatment and prevention, and

- formulating new, more specific and science-based questions.

Renewed focus on cancer

[edit]Recent years have seen an increased perception of a lack of progress in the war on cancer, and renewed motivation to confront the disease.[5][22] On July 15, 2008, the United States Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions convened a panel discussion titled, Cancer: Challenges and Opportunities in the 21st Century.[23] It included interviews with noted cancer survivors such as Arlen Specter, Elizabeth Edwards and Lance Armstrong, who came out of retirement in 2008, returning to competitive cycling "to raise awareness of the global cancer burden".[24]

Livestrong Foundation

[edit]The Livestrong Foundation created the Livestrong Global Cancer Campaign to address the burden of cancer worldwide and encourage nations to make commitments to battle the disease and provide better access to care.[25] In April 2009, the foundation announced that the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan pledged $300 million to fund three important cancer control initiatives – building a cutting-edge cancer treatment and research facility, developing a national cancer control plan and creating an Office of Advocacy and Survivorship.[26] The Livestrong Foundation encourages similar commitments from other nations to combat the disease.

Livestrong Day is an annual event established by the LAF to serve as "a global day of action to raise awareness about the fight against cancer". Individuals from around the world are encouraged to host cancer-oriented events in their local communities and then register their events with the Livestrong website.[27]

21st Century Cancer Access to Life-Saving Early detection, Research and Treatment (ALERT) Act

[edit]The US Senate on 26 March 2009 issued a new bill (S. 717), the 21st Century Cancer Access to Life-Saving Early detection, Research and Treatment (ALERT) Act[28] intended to "overhaul the 1971 National Cancer Act."[7] The bill aims to improve patient access to prevention and early detection by:

- providing funding for research in early detection,

- supplying grants for screening and referrals for treatment, and

- increasing access to clinical trials and information.

Obama-Biden Plan to Combat Cancer

[edit]During their 2008 U.S. presidential campaign then Senators Barack Obama and Joe Biden published a plan to combat cancer that entailed doubling "federal funding for cancer research within 5 years, focusing on NIH and NCI" as well as working "with Congress to increase funding for the Food and Drug Administration."[29][30] Their plan would provide additional funding for:

- research on rare cancers and those without effective treatment options,

- the study of health disparities and evaluation of possible interventions,

- and efforts to better understand genetic factors that can impact cancer onset and outcomes.

President Obama's 2009 economic stimulus package includes $10 billion for the NIH, which funds much of the cancer research in the U.S., and he has pledged to increase federal funding for cancer research by a third for the next two years as part of a drive to find "a cure for cancer in our time".[31][32] In a message published in the July 2009 issue of Harper's Bazaar, President Obama described his mother's battle with ovarian cancer and, noting the additional funding his administration has slated for cancer research, stated: "Now is the time to commit ourselves to waging a war against cancer as aggressive as the war cancer wages against us."[33] On 30 September 2009, Obama announced that $1 billion of a $5 billion medical research spending plan would be earmarked for research into the genetic causes of cancer and targeted cancer treatments.[34]

Cancer-related federal spending of money from the 2009 Recovery Act can be tracked online.[35]

World Cancer Campaign

[edit]The International Union Against Cancer (UICC) has organized a World Cancer campaign in 2009 with the theme, "I love my healthy active childhood," to promote healthy habits in children and thereby reduce their lifestyle-based cancer risk as adults.[36] The World Health Organization is also promoting this campaign[37] and joins with the UICC in annually promoting World Cancer Day on 4 February.[38]

United States' 2022 Moonshot 2.0

[edit]Joe Biden announced Moonshot 2.0, a new front in the war on cancer on 4 February 2022 as part of World Cancer Day.[39][40] As part of the Moonshot 2.0, the Biden administration set a goal of reducing cancer death rate by at least 50 percent over the next 25 years, and improving the experience of living with and surviving cancer. The new effort will signal a "reignition" of the "cancer moonshot" Biden began as vice president under Barack Obama. Moonshot 2.0 was reported to be deeply imbued with personal grief, since the president's son Beau had died the year before from brain cancer.[41]

Biden's new plan calls for a "cancer Cabinet", as well as a new federal agency for high-level research for which his administration is seeking $6.5 billion in seed funding. The president named Danielle Carnival, a neuroscientist who worked on the 2016 cancer initiative, to oversee the moonshot's second version.[42] Moonshot 2.0 would continue work from 2016, involving fostering public-private partnerships, including with biomedical giants, community organizations and academic institutions.

The administration noted that the pandemic showed that researchers collaborating across countries and regulatory barriers could work to produce vaccines whose safety and efficacy are widely regarded as "a marvel of science". On the same day that Moonshot 2.0 was launched, the United Kingdom, a key ally and important research partner, launched their 2022 National War on Cancer [1].

Specifically, the White House announced new goals outlining:

- Working together over the next 25 years, to will cut today's age-adjusted death rate from cancer by at least 50 percent.

- To improve the experience of people and their families living with and surviving cancer.

The Moonshot 2.0 statement detailed actions that the White House stated would drive us toward ending cancer as we know it today

- To diagnose cancer sooner. Noting "we can also greatly expand the cancers we can screen for. Five years ago, detecting many cancers at once through blood tests was a dream. Now new technologies and rigorous clinical trials could put this within our reach"

- To prevent cancer

- To address inequities. Noting a plan to ensure that every community in America – rural, urban, Tribal, and everywhere else – has access to cutting-edge cancer diagnostics, therapeutics, and clinical trials.

- To target the right treatments to the right patients

- To speed progress against the most deadly and rare cancers, including childhood cancers

- To support patients, caregivers, and survivors

- To learn from all patients

- Re-establish White House Leadership with a White House Cancer Moonshot coordinator in the Executive Office of the President, to demonstrate the President and First Lady's personal commitment to making progress and to leverage the whole-of-government approach and national response that the challenge of cancer demands. And additionally form a Cancer Cabinet, and host a White House Cancer Moonshot Summit.

- Issue a Call to Action on Cancer Screening and Early Detection.

United Kingdom's 2022 National War on Cancer

[edit]The United Kingdom initiated a 10-year National war on cancer on World Cancer Day on 4 February 2022.[43] This was on the same day as United States' 2022 Moonshot 2.0 initiative calling for increasing collaboration for a new front in the war on cancer across countries. It was launched by the Health and Social Care Secretary Sajid Javid at the Francis Crick institute in London. Started in the shadow of the third coronavirus wave in the United Kingdom, Sajid Javid promised the National War on Cancer will "make the UK's cancer care system "the best in Europe"",[44] and "show how we are learning the lessons from the pandemic, and apply them to improving cancer services over the next decade".

A set of six new and strengthened priorities were made public including:-

- Increasing the number of people diagnosed at an early stage where treatment can prove much more effective

- Intensifying research on new early diagnostic tools to catch cancer at an earlier stage. A key strategy of the National War on Cancer was building on the latest scientific advances and partnering with the country's technology pioneers. The United Kingdom's NHS-Galleri trial is evaluating a new test that looks for distinct markers in blood to identify cancer risk and was listed as a key example of how technology can transform the way cancer is detected. The test is being trialled across England, with thousands of people already recruited. The UK government wants similar technologies to help form new partnerships and give their National Health Service early, cost effective access to new diagnostics.

- Intensifying research on mRNA vaccines and therapeutics for cancer – this will be achieved through the UK's global leadership and supporting industry to develop new cancer treatments by combining expertise in cancer immunotherapy treatment and the vaccine capabilities developed throughout the pandemic

- Improving prevention of cancer through tackling the big known risk factors such as smoking

- Boosting the cancer workforce

- Tackling disparities and inequalities, including in cancer diagnosis times and ensuring recovery from the pandemic is delivered in a fair way – for instance, the "Help Us Help You" cancer awareness campaign will be directed towards people from more deprived groups and ethnic minorities

Progress

[edit]Though there has been significant progress in the understanding of cancer biology, risk factors, treatments, and prognosis of some types of cancer (such as childhood leukemia[2]) since the inception of the National Cancer Act of 1971, progress in reducing the overall cancer mortality rate has been disappointing.[5][32] Many types of cancer remain largely incurable (such as pancreatic cancer[45]) and the overall death rate from cancer has not decreased appreciably since the 1970s.[46] The death rate for cancer in the U.S., adjusted for population size and age, dropped only 5 percent from 1950 to 2005.[3] As of 2012, WHO reported 8.2 million annual deaths from cancer[47] Heart disease (including both Ischaemic and hypertensive) accounted for 8.5 million annual deaths. Stroke accounted for 6.7 million annual deaths. [48]

There is evidence for progress in reducing cancer mortality.[49] Age-specific analysis of cancer mortality rates has had progress in reducing cancer mortality in the United States since 1955. An August 2009 study found that age-specific cancer mortality rates have been steadily declining since the early 1950s for individuals born since 1925, with the youngest age groups experiencing the steepest decline in mortality rate at 25.9 percent per decade, and the oldest age groups experiencing a 6.8 percent per decade decline.[50] Dr. Eric Kort, the lead author of this study, claims that public reports often focus on cancer incidence rates and underappreciate the progress that has been achieved in reduced cancer mortality rates.[51]

The effectiveness and expansion of available therapies has seen significant improvements since the 1970s. For example, lumpectomy replaced more invasive mastectomy surgery for the treatment of breast cancer.[52] Treatment of childhood leukemia[2] and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) have undergone major advances since the war on cancer began. The drug Gleevec now cures most CML patients, compared to previous therapy with interferon, which extended life for approximately 1 year in only 20-30 percent of patients.[53]

Dr. Steven Rosenberg, chief of surgery at the NCI has said that as of the year 2000, 50% of all diagnosed cases of cancer are curable through a combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.[52][54] Cancer surveillance experts have reported a 15.8 percent decrease in the age-standardized death rate from all cancers combined between 1991 and 2006 along with an approximately 1 percent annual decrease in the rate of new diagnoses between 1999 and 2006.[49] A large portion of this decreased mortality for men was attributable to smoking cessation efforts in the United States.

A 2010 report from the American Cancer Society found that death rates for all cancers combined decreased 1.3% per year from 2001 to 2006 in males and 0.5% per year from 1998 to 2006 in females, largely due to decreases in the 3 major cancer sites in men (lung, prostate, and colorectum) and 2 major cancer sites in women (breast and colorectum). Cancer death rates between 1990 and 2006 for all races combined decreased by 21.0% among men and by 12.3% among women. This reduction in the overall cancer death rates translates to the avoidance of approximately 767,000 deaths from cancer over the 16-year period. Despite these reductions, the report noted, cancer still accounts for more deaths than heart disease in persons younger than 85 years.[55][56]

An improvement in the number of cancer survivors living in the U.S. was indicated in a 2011 report by the CDC and the NCI, which noted that the number of cancer survivors in 2007 (11.7 million) increased by 19% from 2001 (9.8 million survivors). The number of cancer survivors in 1971 was 3 million. Breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers were the most common types of cancer among survivors, accounting for 51% of diagnoses. As of January 1, 2007, an estimated 64.8% of cancer survivors had lived ≥5 years after their diagnosis of cancer, and 59.5% of survivors were aged ≥65 years.[57][58] A continued decline in cancer rates in the U.S. among both women and men, across most major racial groups, and in the most common cancer sites (lung, colon and rectum), was indicated in a 2013 report by the National Cancer Institute. However, the same report indicated an increase from 2000 to 2009 in cancers of the liver, pancreas and uterus.[59]

Challenges

[edit]A multitude of factors have been cited as impeding progress in finding a cure for cancer[5][6] and key areas have been identified and suggested as important to accelerate progress in cancer research.[60] Since there are many different forms of cancer with distinct causes, each form requires different treatment approaches. However, this research could still lead to therapies and cures for many forms of cancer. Some of the factors that have posed challenges for the development of preventive measures and anti-cancer drugs and therapies include the following:

- Inherent biological complexity of the disease:

- number of changes within a cell leading to the cancerous state[61]

- disease heterogeneity due to different tissues of origin[62]

- contribution of numerous genetic and environmental risk factors[63]

- complexity of cellular interactions and cell signaling within the tumor microenvironment[64][65][66]

- suitability of model organisms for understanding human disease.[6]

- Roadblocks to translational medicine[67]

- Challenges of early detection and diagnosis[68][69]

- The drug approval process[70]

- Availability of and access to patients with suitable tumor tissue for research[71]

- Challenges in implementing preventive measures, such as the development and use of preventive drugs and therapies[72][73]

- Choropleth mapping of the changes over time, of the national incidence rate, by cancer type, relative to the population at risk, is a technical challenge.[citation needed]

The public is so jaded by cancer research media attention at the moment... And let's face it, rather embarrassingly, most claimed "breakthroughs" are not proving to significantly advance cancer therapies... It is a real conundrum for researchers today, because "early publicity" is needed for funding, capital raising and professional kudos, but not too helpful for the public who then think that an immediate cure might be just around the corner.

— Professor Brendon Coventry, 9 July 2013[74]

Modern cancer research

[edit]Genome-based cancer research projects

[edit]The rise of a new class of molecular technologies developed during the Human Genome Project opens up new ways to study cancer and holds the promise for the discovery of new aspects of cancer biology that could eventually lead to novel, more effective diagnostics and therapies for cancer patients.[75] [76] [77] These new technologies are capable of screening many biomolecules and genetic variations such as SNPs[78] and copy number variations in a single experiment and are employed within functional genomics and personalized medicine studies.

Speaking on the occasion of the announcement of $1 billion in new funding for genome-based cancer research, Dr. Francis Collins, director of the NIH claimed, "We are about to see a quantum leap in our understanding of cancer."[34] Harold Varmus, after his appointment to be the director of the NCI, said we are in a "golden era for cancer research", poised to profit from advances in our understanding of the cancer genome.[20]

High-throughput DNA sequencing has been used to study the whole genome sequence of two different cancer tissues: a small-cell lung cancer metastasis and a malignant melanoma cell line.[79] The sequence information provides a comprehensive catalog of approximately 90% of the somatic mutations in the cancerous tissue, providing a more detailed molecular and genetic understanding of cancer biology than was previously possible, and offering hope for the development of new therapeutic strategies gleaned from these insights.[80][81]

The Cancer Genome Atlas

[edit]The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), a collaborative effort between the National Cancer Institute and the National Human Genome Research Institute, is an example of a basic research project that is employing some of these new molecular approaches.[82] One TCGA publication notes the following:

Here we report the interim integrative analysis of DNA copy number, gene expression and DNA methylation aberrations in 206 glioblastomas...Together, these findings establish the feasibility and power of TCGA, demonstrating that it can rapidly expand knowledge of the molecular basis of cancer.[83]

In a cancer research funding announcement made by President Obama in September 2009, TCGA project is slated to receive $175 million in funding to collect comprehensive gene sequence data on 20,000 tissue samples from people with more than 20 different types of cancer, in order to help researchers understand the genetic changes underlying cancer. New, targeted therapeutic approaches are expected to arise from the insights resulting from such studies.[34]

Cancer Genome Project

[edit]The Cancer Genome Project at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute aims to identify sequence variants/mutations critical in the development of human cancers. The Cancer Genome Project combines knowledge of the human genome sequence with high throughput mutation detection techniques.[84]

Cancer research supportive infrastructure

[edit]Advances in information technology supporting cancer research, such as the NCI's caBIG project, promise to improve data sharing among cancer researchers and accelerate "the discovery of new approaches for the detection, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cancer, ultimately improving patient outcomes."[85]

Modern cancer treatment

[edit]Cancer clinical trials

[edit]Researchers are considering ways to improve the efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and overall success rate of cancer clinical trials.[86]

Increased participation in rigorously designed clinical trials would increase the pace of research. Currently, about 3% of people with cancer participate in clinical trials; more than half of them are patients for whom no other options are left, patients who are participating in "exploratory" trials designed to burnish the researchers' résumés or promote a drug rather than to produce meaningful information, or in trials that will not enroll enough patients to produce a statistically significant result.[citation needed]

Targeted tumor treatment

[edit]A major challenge in cancer treatment is to find better ways to specifically target tumors with drugs and chemotherapeutic agents in order to provide a more effective, localized dose and to minimize exposure of healthy tissue in other parts of the body to the potentially adverse effects of the treatments. The accessibility of different tissues and organs to anti-tumor drugs contributes to this challenge. For example, the blood–brain barrier blocks many drugs that may otherwise be effective against brain tumors. In November 2009, a new, experimental therapeutic approach for treating glioblastoma was published in which the anti-tumor drug Avastin was delivered to the tumor site within the brain through the use of microcatheters, along with mannitol to temporarily open the blood–brain barrier permitting delivery of the chemotherapy into the brain.[87][88]

Public education and support

[edit]An important aspect to the war on cancer is improving public access to educational and supportive resources, to provide individuals with the latest information about cancer prevention and treatment, as well as access to support communities. Resources have been created by governmental and other organizations to provide support for cancer patients, their families and caregivers, to help them share information and find advice to guide decision making.[89][90][91][92][93][94][95]

See also

[edit]- American Cancer Society

- American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) project CancerProgress[96]

- caBIG

- International Agency for Research on Cancer

- International Union Against Cancer

- National Cancer Institute

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- Stand Up to Cancer

- The Cancer Genome Atlas project

- War metaphors in cancer

- War as metaphor

References

[edit]- ^ a b "National Cancer Act of 1971". National Cancer Institute. 16 February 2016. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c Kersey, John H. (1997). "Fifty Years of Studies of the Biology and Therapy of Childhood Leukemia". Blood. 90 (11): 4243–4251. doi:10.1182/blood.V90.11.4243. PMID 9373234.

- ^ a b Kolata, Gina (April 24, 2009). "As Other Death Rates Fall, Cancer's Scarcely Moves". The New York Times. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

- ^ "The War on Cancer A Progress Report for Skeptics". Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 34, no. 1. January–February 2010. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Hughes R. (2006). The War on Cancer: An Anatomy of Failure, a Blueprint for the Future (book review). Vol. 295. pp. 2891–2892. doi:10.1001/jama.295.24.2891. ISBN 978-1-4020-3618-7.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Sharon Begley (September 15, 2008). "Rethinking the War on Cancer". Newsweek. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ a b "Kennedy, Hutchison Introduce Bill To Overhaul 1971 National Cancer Act". Medical News Today. March 30, 2009. Retrieved March 30, 2009.

- ^ Kolata, Gina (November 4, 2013). "Hopeful Glimmers in Long War on Cancer". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ "Milestone (1971): National Cancer Act of 1971". Developmental Therapeutics Program Timeline. National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ^ "National Cancer Act, Legislative History". Office of Government and Congressional Relations. National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ^ Mukherjee, Siddhartha (2010). The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-0795-9. OCLC 464593321.

- ^ Katz, Esther. "LASKER, Mary Woodard Reinhardt. November 30, 1900-February 21, 1994". Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ Merenda, Christine (2012). "How Far Has the War on Cancer Come in the Past 40 Years?". ONS Connect. 27 (6): 20. PMID 22774344. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ Andrew von Eschenbach. "Director's Update: August 27, 2003: Eliminating Suffering and Death from Cancer by 2015: What Should NCI Contribute to the Challenge Goal?". Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ^ Dr. Andrew von Eschenbach (September 2005). "Eliminating the Suffering and Death Due to Cancer by 2015". Medical Progress Bulletin, Issue 1. Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

- ^ Margaret Foti, Ph.D., M.D. (2005-04-15). "Written Testimony Submitted to The House Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies". AACR. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kaiser, Jocelyn (28 February 2003). "NCI Goal Aims for Cancer Victory by 2015". Science. 299 (5611): 1297–1298. doi:10.1126/science.299.5611.1297b. PMID 12610266. S2CID 37245832.

- ^ John E. Niederhuber (2009-10-06). "Global Cancer Control: An Essential Duty". NCI Cancer Bulletin. NCI. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

- ^ Bill Robinson (2010-07-12). "Harold Varmus Becomes Fourteenth Director of the National Cancer Institute". NCI Cancer Bulletin. Retrieved 2010-08-04.

- ^ a b "Harold Varmus Returns To Politics". NPR's Science Friday. 2010-07-16. Retrieved 2010-08-04.

- ^ Harold Varmus: NCI Town Hall Meeting (excerpts). NCI. 2010-07-12. Archived from the original on 2013-08-01. Retrieved 2010-08-04.

- ^ Bernadine Healy (2008-06-12). "We Need a New War on Cancer". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 2009-10-26.

- ^ Stand Up to Cancer (2008-07-15). "Renewing the War on Cancer". YouTube. Archived from the original (video) on 2009-11-25. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ^ Sal Ruibal (2008-09-10). "Armstrong coming out of retirement for another Tour". USA Today. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- ^ "A Global Movement To End Cancer". Lance Armstrong Foundation. Archived from the original on 2009-08-30. Retrieved 2009-10-02. [third-party source needed]

- ^ "LIVESTRONG Global Cancer campaign announces Hashemite Kingdom Of Jordan's commitment of $300 million to fund three cancer control initiatives". Lance Armstrong Foundation. 2009-04-16. Archived from the original on 2009-04-20. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ^ "LIVESTRONG Day home page". Lance Armstrong Foundation. Archived from the original on 2009-09-27. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- ^ Senators Edward Kennedy and Kay Bailey Hutchison (2009-03-26). "S.717: 21st Century Cancer ALERT (Access to Life-Saving Early detection, Research and Treatment) Act". GovTrack.us, 111th Congress (2009–2010). Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ^ "The Obama-Biden Plan To Combat Cancer" (PDF). Organizing for America. 2008-09-06. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- ^ The Senior Vote Team (2008-09-06). "Obama-Biden release plan to combat cancer". Organizing for America Community Blog. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- ^ Foster, Kate (April 26, 2009). "Obama makes $10bn pledge to find cure for global killer 'in our time'". Scotsman.com News. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- ^ a b Kolata, Gina (April 23, 2009). "Advances Elusive in the Drive to Cure Cancer". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- ^ Lennon, Christine (2009-06-03). "Ovarian Cancer: Fighting For A Cure". Harper's Bazaar. Archived from the original on 2009-06-10. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

- ^ a b c Charles, Deborah (2009-09-30). "Obama announces $5 billion for new medical research". Reuters. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ^ "Recovery.gov: Track the Money (search term=cancer)". United States government. Retrieved 2009-11-14.

- ^ "World Cancer Campaign". UICC. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ "Cancer". WHO. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ "World Cancer Day". WHO. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: President Biden Reignites Cancer Moonshot to End Cancer as We Know It". The White House. 2022-02-02. Retrieved 2022-02-05.

- ^ "Cancer Moonshot - National Cancer Institute". www.cancer.gov. 2016-02-01. Retrieved 2022-02-05.

- ^ "'Moonshot' 2.0: Biden announces new front in war on cancer". uk.news.yahoo.com. 2 February 2022. Retrieved 2022-02-05.

- ^ Flannery, Russell (August 8, 2022). "Meet The Scientist Coordinating Joe Biden's New Cancer Moonshot". Forbes. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ "Health and Social Care Secretary to launch new 10-year 'national war on cancer'". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2022-02-05.

- ^ "Health Secretary developing "new vision" as part of 'war on cancer'". The Independent. 2022-01-18. Retrieved 2022-02-05.

- ^ "Pancreatic Cancer Report Urges Changes in Clinical Trials". NCI Cancer Bulletin. NCI. 2009-11-03. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

- ^ Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, Stinchcomb DG, Howlader N, Horner MJ, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Feuer EJ, Altekruse SF, Lewis DR, Clegg L, Eisner MP, Reichman M, Edwards BK. "SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2005, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD". Retrieved 2008-10-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "WHO: Cancer". Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ^ "WHO: The Top 10 Causes of Death". Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ^ a b "Progress Has Been Made in War on Cancer, but Still Many Challenges". Science Daily. 2010-03-19. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- ^ Kort, Eric J.; Nigel Paneth; George F. Vande Woude (2009-08-15). "The Decline in U.S. Cancer Mortality in People Born since 1925". Cancer Research. 69 (16): 6500–5. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0357. PMC 4326089. PMID 19679548.

- ^ Moore, Jeremy (2009-08-13). "Cancer mortality rates experience steady decline". EurekAlert. Retrieved 2009-08-30.

- ^ a b "History of Cancer". Waging War on Cancer. Episode 101. 2009-08-23.

- ^ Claudia Dreifus (2009-11-02). "Researcher Behind the Drug Gleevec: A Conversation with Brian K. Druker, M.D." The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-11-03.

- ^ "Millennium 2000: Cancer (transcript)". CNN. 2000-01-02. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

- ^ Jemal, A; Siegel, R; Xu, J; Ward, E (2010-07-07). "Cancer Statistics, 2010". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 60 (5): 277–300. doi:10.3322/caac.20073. PMID 20610543. S2CID 36759023.

- ^ Bill Hendrick (2010-07-08). "Cancer Death Rates Are Dropping in U.S." WebMD Health News. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- ^ "Cancer Survivors --- United States, 2007". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). CDC. 11 March 2011. pp. 269–272. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Belluck, Pam (10 March 2011). "20% Rise Seen in Number of Survivors of Cancer". New York Times. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Editorial Staff (2013-01-08). "Cancer U.S. cancer rates dip". TriMed Media. Retrieved 2013-01-09.

- ^ "NCI Think Tanks in Cancer Biology". NCI. 2004. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ^ "Cancer - A Complex Disease". Understanding Cancer Series: Genetic Variation (SNPs). NCI. 2009-09-01. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ "Cancer Fact Sheet". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. CDC. 2002-08-30. Archived from the original on July 5, 2004. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ Amundadottir, LT; Thorvaldsson, S; Gudbjartsson, DF; Sulem, P; Kristjansson, K; Arnason, S; Gulcher, JR; Bjornsson, J; et al. (2004). "Cancer as a Complex Phenotype: Pattern of Cancer Distribution within and beyond the Nuclear Family". PLOS Med. 1 (3): e65. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0010065. PMC 539051. PMID 15630470.

- ^ "The Tumor and its Microenvironment: How they communicate, and why it's important". AACR. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ Matrisian, Lynn M.; Cunha, Gerald R.; Mohla, Suresh (2001). "Epithelial-Stromal Interactions and Tumor Progression: Meeting Summary and Future Directions". Cancer Research. 61 (9): 3844–3846. PMID 11325861.

- ^ Gina Kolata (2009-12-28). "Old Ideas Spur New Approaches in Cancer Fight". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-01-17.

- ^ "About Science Translational Medicine (journal)". AAAS. May 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ Singer, Natasha (2009-07-16). "In Push for Cancer Screening, Limited Benefits". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-10-26.

- ^ "PDQ Cancer Information Summaries: Screening/Detection (Testing for Cancer)". NCI. January 1980. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ^ Harris, Gardiner (2009-09-15). "Where Cancer Progress Is Rare, One Man Says No". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ Harmon, Amy (2010-12-28). "Enlisting the Dying for Clues to Save Others". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- ^ Gina Kolata (2009-11-13). "Medicines to Deter Some Cancers Are Not Taken". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- ^ Parker-Pope, Tara (2009-12-14). "When Lowering the Odds of Cancer Isn't Enough". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ^ Brendon Coventry (8 July 2013). "Found: a new drug mix to nix breast cancer". The Conversation. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ "NCI Director's Challenge: Toward a Molecular Classification of Cancer". NCI's Cancer Diagnosis Program. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ^ Bernadine Healy M.D. (2008-10-23). "Breaking Cancer's Gene Code". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ^ "Empowering Cancer Research". NCI's "The Nation's Investment in Cancer Research". Archived from the original on 2008-06-16. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ^ "SNPs May Be The Solution". Understanding Cancer Series: Genetic Variation (SNPs). National Cancer Institute. 2006-09-01. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ Pleasance, Erin D.; Cheetham, R. Keira; Stephens, Philip J.; McBride, David J.; Humphray, Sean J.; Greenman, Chris D.; Varela, Ignacio; Lin, Meng-Lay; et al. (2009). "A comprehensive catalogue of somatic mutations from a human cancer genome". Nature. 463 (7278): 191–6. doi:10.1038/nature08658. PMC 3145108. PMID 20016485.

- ^ Karol Sikora (2009-12-18). "We're winning the war on cancer". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on December 20, 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ^ Akst, Jef (2009-12-16). "Cancer Genomes Sequenced". News blog. The-Scientist.com. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ^ "The Cancer Genome Atlas website". National Cancer Institute and the National Human Genome Research Institute. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- ^ McLendon, R.; Friedman, Allan; Bigner, Darrell; Van Meir, Erwin G.; Brat, Daniel J.; M. Mastrogianakis, Gena; Olson, Jeffrey J.; Mikkelsen, Tom; et al. (2008-10-23). "Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways". Nature. 455 (7216): 1061–1068. Bibcode:2008Natur.455.1061M. doi:10.1038/nature07385. PMC 2671642. PMID 18772890.

- ^ "The Cancer Genome Project website". Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. Archived from the original on 2013-07-02. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- ^ "About caBIG". NCI's cancer Biomedical Informatics Grid website. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

- ^ Patlak, Margie; Nass, Sharyl (2008). Improving the Quality of Cancer Clinical Trials: Workshop Summary. National Academies Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-309-11668-8.

- ^ Grady, Denise (2009-11-16). "Breaching a Barrier to Fight Brain Cancer". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ^ "World's First Delivery of Intra-Arterial Avastin Directly Into Brain Tumor". Science Daily. 2009-11-17. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ^ "Cancer Information Service". NCI. January 1980. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ "Need Answers? 1-800-227-2345". ACS. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

- ^ "Cancer Prevention and Control". CDC. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- ^ "World Health Organization's Cancer website". WHO. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- ^ "Cancer Compass, Community for cancer patients & caregivers". Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- ^ "Cancer Survivors Network". ACS. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- ^ "CancerTV". Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- ^ "About CancerProgress.Net". CancerProgress. American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). 2011. Retrieved May 10, 2012.