Spanish corvette Tornado

Painting of CSS Alabama, sister ship of Tornado, on display at the US Navy's Naval Historical Center

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | CSS Texas |

| Launched | 1863 |

| Commissioned | 1865 |

| Fate | Purchased by Chile for £75,000. |

| Owner | Chilean Navy |

| Acquired | February 1866 |

| Renamed | Pampero |

| Fate | Captured off Madeira by the Spanish frigate Gerona. |

| Acquired | 1870 |

| Commissioned | 1870 |

| Decommissioned | 1938 |

| Renamed | Tornado |

| Captured | 28 October 1873 |

| Fate |

|

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement | 2,100 tons[1] |

| Length | 231 ft (70 m)[1] |

| Beam | 33 ft (10 m)[1] |

| Propulsion | Steam, sail |

| Speed | 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph)[1] |

| Range | 1,700 miles (2,700 km)[1] |

| Armament | |

Tornado was a bark-rigged screw steam corvette[2][3] of the Spanish Navy, first launched at Clydebank, Scotland in 1863, as the Confederate raider CSS Texas. She is most famous for having captured the North American filibustering ship Virginius, which led to the "Virginius Affair", which afterwards led to the Spanish-American Crisis of 1873.

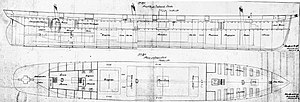

Design and construction

[edit]The ship was built as the Confederate raider CSS Texas, but was seized by the British government in 1863 and acquired in 1865.[4] She was purchased by the Chilean government for £75,000, through Isaac Campbell & Co, in February 1866.[5]

In early 1862, Lt. George T. Sinclair was sent to England, with orders to build a clipper propeller for cruising purposes, and to take command of her when she was ready for sea.[5][dead link] His instructions were to confer with Commander Bulloch in Liverpool, as to the design of the vessel, and the building, fitting out and arming of her.[5][dead link] Bulloch received orders to help Sinclair with funds and advice. He showed Sinclair the drawings and specifications for CSS Alabama, also the contract with Lairds, and they both decided to use these as a basis for the new cruiser.[5][dead link]

What Sinclair did, was to arrange, with the help of the Confederate diplomat James M. Mason, for an issue of bonds, each equal to 25 bales of cotton, weight 12,500 lb (5,700 kg). Seven individuals took up these bonds, and were effectively the owners of this new vessel.[5][dead link] The new cruiser was contracted by James and George Thomson of Glasgow, in October 1862. The same firm that was contracted to build an ironclad ram for Lt. North. Pampero was modeled on Alabama, even though she was somewhat larger.[6]

Pampero was to be 231 feet (70 m) in length, 33 feet (10 m) in breadth, powered by both sail and steam. Bark rigged, she was equipped for cruising under canvas or steam, with telescopic funnels, and a raise-able screw.[6] Similar, but larger engines to Alabama were placed below the waterline for protection. Her frame was iron, with a mixture of iron and wood for the planking.[6] Her armament was to be three 8-inch (203 mm) pivot guns, and a broadside battery of four or more guns. The original contract called for Pampero to be ready for sea by July 1863, but the schedule could not be maintained. Guns and gun carriages were ordered, and Sinclair received £10,000 ($40,000) from Bulloch, and perhaps more. For his crew, Sinclair made arrangements for some men to come out from Baltimore.[7] By the spring of 1863, Sinclair was becoming very concerned about Pampero, and feared that the British government would not permit the departure of any vessel suspected to be Confederate.[7]

He visited Paris to discuss with John Slidell the possibility of transferring the vessel to France. Slidell suggested Hamburg in Germany would be a better alternative. However, Sinclair investigated this, but did not proceed with it.[5][dead link] Meanwhile, the completion of Pampero was further delayed by labor troubles, and the seizure of Alexandria, another Confederate vessel in production at Lairds, by the British government. The Alexandria trial was indecisive, and Mason put off the launching of Pampero until a final verdict was reached.[5][dead link]

Pampero herself first came to the attention of Thomas H. Dudley, United States Consul in Liverpool, in the spring of 1863, when he made an investigative tour of Northern England and Scotland, looking for any warships being built for the Confederates.[5][dead link] He learned that Thomsons were building a screw steamer "of about 1500 tons," designed for great speed.[5][dead link] He was told that she was to have an angle-iron frame and teak planking, and he found that among the workmen it was generally believed that she was for the South.

On his next trip to Scotland in August 1863, his suspicions increased as new details on the vessel came to light. The builders insisted that the boat was for the Turkish government, but Dudley`s informants in the yard insisted the boat was for the Confederates, being supervised by the same men as those who supervised the building of the ironclad ram. Dudley left behind a spy in Thomsons yard, who soon reported that the vessel was rigged in the same manner as Alabama, the drawings of which, he was told, were in Glasgow.[5][dead link]

Pampero, by a Mrs. Galbraith, the vessel finally slid down the slipway on 29 October 1863. On 10 November, the American consul in Glasgow, W. L. Underwood formally requested that Pampero be detained.[5][dead link] Although the British government did not make any immediate legal moves, in late November a British warship was moored abreast of Pampero, and she was placed under a 24-hour scrutiny by customs officers. Court proceedings against Pampero commenced on 18 March 1864, and were never satisfactorily concluded.

Capture

[edit]

During the Chincha Islands War, the South American allies sent agents to European shipyards in search of unsold warships originally laid down for the Confederate states; Peru purchased two screw corvettes in France and Chile, purchased two in Britain, Tornado and the Chilean corvette Abtao[8] She set sail from Leith with a British register, British flag, with a British crew, after having been duly examined by the Custom-house authorities, on 19 August 1866.[9][10] Bound for a neutral destination, she had no Chilean men on board.[11]

She should have been in rendezvous with the British filibustering ship steamer Greathem Hall, aiming to interfere against the Spanish trade. However, the latter was captured by HMS Caledonia and taken into Portland. Pampero (now named Tornado) waited patiently in the rendezvous point, until the crew were ordered to re-coal and head for the desolate islands of Fernando de Noronha, an old pirate haunt off the Brazilian coast, in order to collect unpaid wages and bonuses offered for the delivery of the vessel.[12]

The Spanish frigate, brought strict orders from the Spanish government to capture these ships.[13] However, the Peruvian vessels made it to Latin American waters but the Chilean Pampero was about to be captured. Gerona sailed from Cádiz in the early morning of the 20th instant, arriving at Madeira, Portugal on 22nd instant. At 6:15 in the evening; before arriving at the anchoring ground, she discovered a suspicious steamer weighing anchor and apparently getting ready to put to sea, for which reason the commander of Gerona, Don Benito Escalera, thought fit to proceed towards her to see if he could obtains news, and to be at the same time in readiness to follow in her track, should she turn out to be either of the vessels indicated to him by the Spanish government.[14]

At 8:00pm, the frigate, thinking that she perceived that Tornado was putting herself in motion, and having been confirmed in that opinion by the showing of the signal agreed upon on board the Spanish schooner, commenced to move in pursuit.[14] The course which Tornado took was in every way suspicious, for she kept as close into the north-west shore of this island as she could, coasting along it at a very short distance as far as Cape Tristão, where she put to sea steering towards the north.[14]

Notwithstanding that Tornado was some distance off at 10:30pm, and at a distance of more than 4 miles (6.4 km) from the coast, the captain of Gerona, a slower ship,[15] resolved to call her attention by discharging at her a cannon loaded with blank cartridge, but seeing that she kept on her course, he fired another shotted cannon at her, and this he repeated three times, Tornado then stopped.[14]

He sent on board of her tow boats manned and tow officers to examine her, which was done in due form, although it could not be affirmed positively whether she carried munitions of war or not on account of the great quantity of coal with which she was stowed. The commander made the captain come on board Gerona, and this latter answered the questions that were put to him with insolent and insulting words so that he was obliged to be called to order. He then ordered the said captain to return to Tornado, which was navigated to Cadiz by the 1st Lieutenant Don Manuel del Bustillo, 2nd Lieutenant, four midshipmen, one engineer, and 51 armed men, and the crew of Tornado comprising 55 men, among whom were five Portuguese taken on board at Funchal, were transferred to Gerona.[14]

Captain John MacPherson and the crew of Tornado were treated with great severity, both on their way to Cádiz and after their arrival in that city. The case led to negotiations between the British and Spanish governments expressed the opinion that the Spanish government had no right to treat the crew as prisoners of war, much less to chain them up.[16]

Spanish service

[edit]

She was brought into Spanish service as Tornado,[13] and rated as screw corvette. During the Ten Years' War, she saw service in Cuban waters and had a notorious incident with the American filibustering steamer Virginius, that had been bought for the purpose of being used for landing military expeditions on Cuba in aid of the insurgents. Virginius had been engaged in this work for months, being even called by one of the Havana newspapers as the famous filibuster steamer Virginius.[17]

On 31 October 1873, she was bound from Kingston, Jamaica to some point in Cuba, flying the US flag, and carrying a cargo of war material. Having a crew of 52 (chiefly Americans and Britons) and 103 passengers (mostly Cubans),[17] Virginius was sighted by Tornado, and she immediately fled in a northerly direction toward Jamaica, but was chased by her, captured and taken into Santiago de Cuba. Fifty-three of the crew and passengers were condemned to death by court-martial, and between 4–8 November, were shot; among them were eight American citizens.[17]

The capture on the high seas of a vessel vearing the American flag, presents a very grave question, which will need investigation; ...and if it prove that an American citizen has been wrongfully executed, this government will require most ample reparation.[17]

Relations between Spain and the United States became strained, and war seemed imminent, but on 8 December, the Spanish government agreed to surrender Virginius to the US on 16 December, to deliver the survivors of the crew and passengers to a US warship at Santiago, and to salute the US flag at Santiago on 25 December if it was not proved before that date that Virginius was not entitled to sail under American colors. Virginius foundered off Cape Hatteras as she was being towed to the United States by Ossipee. George Henry Williams, the Attorney General of the United States decided before 25 December that Virginius was the property of General Quesada and other Cubans, and had had no right to carry the American flag.

Under an agreement of the 27 February 1875, the Spanish government paid to the United States an indemnity of $80,000 for the execution of the Americans, and another indemnity to the British government.

Tornado was converted to a torpedo-training vessel in 1886. From 1898 until her destruction by the Nationalist aviation in 1938, she served as a hospice for poor children of sailors and fishermen killed or drowned in maritime accidents, in the port of Barcelona.[18] She was finally broken up in 1939.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Christian de Saint Hubert, "The Early Spanish Steam Warships 1834-1870". Warship International 1983.

- ^ Hagan, p. 180

- ^ Albertson, p. 17

- ^ Jack Greene, Alessandro Massignani, p. 275

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "When Liverpool Was Dixie". www.whenliverpoolwasdixie.co.uk. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012.

- ^ a b c McKenna, p. 163.

- ^ a b McKenna, p. 164.

- ^ Website of the Chilean Navy Abtao, corbeta (1º) Archived 2012-05-16 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on 6 December 2011

- ^ Bentinck, p. 30.

- ^ Bentinck p.9

- ^ Urrutia, p. 320.

- ^ Graham, p. 62.

- ^ a b Sondhaus, p. 98.

- ^ a b c d e House of Commons, p. 18.

- ^ Greene, p. 276.

- ^ Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events, p. 688.

- ^ a b c d Rhodes, p. 93.

- ^ Universitat de Barcelona. Centre d'Estudis Històrics Internacionals, p. 226.

Sources

[edit]- Accounts and papers of the House of Commons Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons

- Albertson, Mark (2007). They'll Have to Follow You!: The Triumph of the Great White Fleet. Mustang, Oklahoma, US: Tate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60462-145-7.

- Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events: Embracing political, military, and ecclesiastical affairs; public documents; biography, statistics, commerce, finance, literature, science, agriculture, and mechanical industry, Vol. 6.

- Bentinck, G. C. Case of the Tornado.

- Graham, Eric J. (2008). Clyde Built: blockade runners, cruisers and armoured rams of the American Civil War. Birlinn Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84158-584-0.

- Hagan, Kenneth J. (1991). This People's Navy: The Making of American Sea Power. New York: The Free Press. ISBN 0-02-913471-4.

- History of the United States: From the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896, Vol. VII (in Eight Volumes)

- McKenna, Joseph (2010). British Ships in the Confederate Navy. McFarland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7864-4530-1.

- Greene, Jack; Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads at war: the origin and development of the armored warship, 1854-1891. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-938289-58-6.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval Warfare, 1815-1914. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21478-5.

- (in Spanish) Carlos López Urrutia. Historia de la Marina de Chile

- (in Spanish) Indice Historico Español Vol. 39,Nº114 . Universitat de Barcelona. Centre d'Estudis Històrics Internacionals

External links

[edit]- https://web.archive.org/web/20120323132501/http://www.whenliverpoolwasdixie.co.uk/pamp.htm

- http://www.spanamwar.com/spanwoodenbcruisers.htm

- (in Spanish) http://www.ligamar.cl/revis9/57.htm Archived 2013-04-19 at the Wayback Machine