Chlorotrianisene

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Tace, Estregur, Anisene, Clorotrisin, Merbentyl, Triagen, others |

| Other names | CTA; Trianisylchloroethylene; tri-p-Anisylchloroethylene; TACE; tris(p-Methoxyphenyl)-chloroethylene; NSC-10108 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Multum Consumer Information |

| Routes of administration | By mouth[1][2] |

| Drug class | Nonsteroidal estrogen |

| ATC code | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Mono-O-demethylation (liver CYP450)[3][4] |

| Metabolites | Desmethylchlorotrianisene[3][4] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.472 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C23H21ClO3 |

| Molar mass | 380.87 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Chlorotrianisene (CTA), also known as tri-p-anisylchloroethylene (TACE) and sold under the brand name Tace among others, is a nonsteroidal estrogen related to diethylstilbestrol (DES) which was previously used in the treatment of menopausal symptoms and estrogen deficiency in women and prostate cancer in men, among other indications, but has since been discontinued and is now no longer available.[5][6][7][1][8] It is taken by mouth.[1][2]

CTA is an estrogen, or an agonist of the estrogen receptors, the biological target of estrogens like estradiol.[7][1][9][10] It is a high-efficacy partial estrogen and shows some properties of a selective estrogen receptor modulator, with predominantly estrogenic activity but also some antiestrogenic activity.[11][12] CTA itself is inactive and is a prodrug in the body.[2][13]

CTA was introduced for medical use in 1952.[14] It has been marketed in the United States and Europe.[14][6] However, it has since been discontinued and is no longer available in any country.[1][15]

Medical uses

[edit]CTA has been used in the treatment of menopausal symptoms and estrogen deficiency in women and prostate cancer in men, among other indications.[7][1] It has been used to suppress lactation in women.[16] CTA has been used in the treatment of acne as well.[17][18][19]

| Route/form | Estrogen | Dosage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Estradiol | 1–2 mg 3x/day | |

| Conjugated estrogens | 1.25–2.5 mg 3x/day | ||

| Ethinylestradiol | 0.15–3 mg/day | ||

| Ethinylestradiol sulfonate | 1–2 mg 1x/week | ||

| Diethylstilbestrol | 1–3 mg/day | ||

| Dienestrol | 5 mg/day | ||

| Hexestrol | 5 mg/day | ||

| Fosfestrol | 100–480 mg 1–3x/day | ||

| Chlorotrianisene | 12–48 mg/day | ||

| Quadrosilan | 900 mg/day | ||

| Estramustine phosphate | 140–1400 mg/day | ||

| Transdermal patch | Estradiol | 2–6x 100 μg/day Scrotal: 1x 100 μg/day | |

| IM or SC injection | Estradiol benzoate | 1.66 mg 3x/week | |

| Estradiol dipropionate | 5 mg 1x/week | ||

| Estradiol valerate | 10–40 mg 1x/1–2 weeks | ||

| Estradiol undecylate | 100 mg 1x/4 weeks | ||

| Polyestradiol phosphate | Alone: 160–320 mg 1x/4 weeks With oral EE: 40–80 mg 1x/4 weeks | ||

| Estrone | 2–4 mg 2–3x/week | ||

| IV injection | Fosfestrol | 300–1200 mg 1–7x/week | |

| Estramustine phosphate | 240–450 mg/day | ||

| Note: Dosages are not necessarily equivalent. Sources: See template. | |||

Side effects

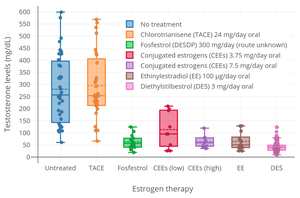

[edit]In men, CTA can produce gynecomastia as a side effect.[20][21] Conversely, it does not appear to lower testosterone levels in men, and hence does not seem to have a risk of hypogonadism and associated side effects in men.[22]

Pharmacology

[edit]

CTA is a relatively weak estrogen, with about one-eighth the potency of DES.[2][12] However, it is highly lipophilic and is stored in fat tissue for prolonged periods of time, with its slow release from fat resulting in a very long duration of action.[2][12][24] CTA itself is inactive; it behaves as a prodrug to desmethylchlorotrianisene (DMCTA),[3][4] a weak estrogen that is formed as a metabolite via mono-O-demethylation of CTA in the liver.[2][13] As such, the potency of CTA is reduced if it is given parenterally instead of orally.[2]

Although it is referred to as a weak estrogen and was used solely as an estrogen in clinical practice, CTA is a high-efficacy partial agonist of the estrogen receptor.[12] As such, it is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), with predominantly estrogenic effects but also with antiestrogenic effects, and was arguably the first SERM to ever be introduced.[11] CTA can antagonize estradiol at the level of the hypothalamus, resulting in disinhibition of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis and an increase in estrogen levels.[12] Clomifene and tamoxifen were both derived from CTA via structural modification, and are much lower-efficacy partial agonists than CTA and hence much more antiestrogenic in comparison.[12][9] As an example, chlorotrianisene produces gynecomastia in men,[21] albeit reportedly to a lesser extent than other estrogens,[25] while clomifene and tamoxifen do not and can be used to treat gynecomastia.[26]

CTA at a dosage of 48 mg/day inhibits ovulation in almost all women.[27] Conversely, it has been reported that CTA has no measurable effect on circulating levels of testosterone in men.[22] This is in contrast to other estrogens, like diethylstilbestrol, which can suppress testosterone levels by as much as 96%—or to an equivalent extent as castration.[22] These findings suggest that CTA is not an effective antigonadotropin in men.[22]

Chemistry

[edit]Chlorotrianisene, also known as tri-p-anisylchloroethylene (TACE) or as tris(p-methoxyphenyl)chloroethylene, is a synthetic nonsteroidal compound of the triphenylethylene group.[5][7][1] It is structurally related to the nonsteroidal estrogen diethylstilbestrol and to the SERMs clomifene and tamoxifen.[1][12][9]

History

[edit]CTA was introduced for medical use in the United States in 1952, and was subsequently introduced for use throughout Europe.[14][6] It was the first estrogenic compound of the triphenylethylene series to be introduced.[11] CTA was derived from estrobin (DBE), a derivative of the very weakly estrogenic compound triphenylethylene (TPE), which in turn was derived from structural modification of diethylstilbestrol (DES).[2][12][24][28] The SERMs clomifene and tamoxifen, as well as the antiestrogen ethamoxytriphetol, were derived from CTA via structural modification.[12][9][29][30]

Society and culture

[edit]Generic names

[edit]Chlorotrianisene is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, and BAN.[5][6][7] It is also known as tri-p-anisylchloroethylene (TACE).[5][6][7]

Brand names

[edit]CTA has been marketed under the brand names Tace, Estregur, Anisene, Clorotrisin, Merbentyl, Merbentul, and Triagen among many others.[5][6]

Availability

[edit]CTA is no longer marketed and hence is no longer available in any country.[1][15] It was previously used in the United States and Europe.[14][6]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sweetman SC, ed. (2009). "Sex hormones and their modulators". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. p. 2085. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Meikle AW (24 April 2003). Endocrine Replacement Therapy in Clinical Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 486–. ISBN 978-1-59259-375-0.

- ^ a b c Ruenitz PC, Toledo MM (August 1981). "Chemical and biochemical characteristics of O-demethylation of chlorotrianisene in the rat". Biochem. Pharmacol. 30 (16): 2203–7. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(81)90088-5. PMID 7295335.

- ^ a b c Jordan VC (1986). Estrogen/antiestrogen Action and Breast Cancer Therapy. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-299-10480-1.

- ^ a b c d e Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 263–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 219–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Morton IK, Hall JM (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 73–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- ^ Cox RL, Crawford ED (December 1995). "Estrogens in the treatment of prostate cancer". The Journal of Urology. 154 (6): 1991–8. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66670-9. PMID 7500443.

- ^ a b c d Luniwal A, Jetson R, Erhardt P (2012). "Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators". In Fischer J, Ganellin CR, Rotella DP (eds.). Analogue-Based Drug Discovery III. pp. 165–185. doi:10.1002/9783527651085.ch7. ISBN 9783527651085.

- ^ Jordan VC, Lieberman ME (September 1984). "Estrogen-stimulated prolactin synthesis in vitro. Classification of agonist, partial agonist, and antagonist actions based on structure". Molecular Pharmacology. 26 (2): 279–85. PMID 6541293.

- ^ a b c Fischer J, Ganellin CR, Rotella DP (15 October 2012). Analogue-based Drug Discovery III. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-3-527-65110-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sneader W (23 June 2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 198–. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

- ^ a b Hadden J (9 November 2013). Pharmacology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 249–. ISBN 978-1-4615-9406-2.

- ^ a b c d William Andrew Publishing (22 October 2013). Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition. Elsevier. pp. 980–. ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3.

- ^ a b http://www.micromedexsolutions.com/micromedex2/[permanent dead link]

- ^ Vorherr H (2 December 2012). The Breast: Morphology, Physiology, and Lactation. Elsevier Science. pp. 203–. ISBN 978-0-323-15726-1.

- ^ Schirren C (1961). "Die Sexualhormone". Therapie der Haut- und Geschlechtskrankheiten. pp. 470–549. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-94850-3_6. ISBN 978-3-642-94851-0.

- ^ Kile RL (August 1953). "The treatment of acne with TACE". J Invest Dermatol. 21 (2): 79–81. doi:10.1038/jid.1953.73. PMID 13084969.

- ^ Welsh AL (April 1954). "Use of synthetic estrogenic substance chlorotrianisene (TACE) in treatment of acne". AMA Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 69 (4): 418–27. doi:10.1001/archderm.1954.01540160020004. PMID 13147544.

- ^ Dao TL (1975). "Pharmacology and Clinical Utility of Hormones in Hormone Related Neoplasms". In Sartorelli AC, Johns DG (eds.). Antineoplastic and Immunosuppressive Agents. pp. 170–192. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-65806-8_11. ISBN 978-3-642-65806-8.

- ^ a b Li JJ (3 April 2009). Triumph of the Heart: The Story of Statins. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-19-532357-3.

- ^ a b c d Ghanadian R (6 December 2012). The Endocrinology of Prostate Tumours. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-94-011-7256-1.

- ^ a b c Shearer RJ, Hendry WF, Sommerville IF, Fergusson JD (December 1973). "Plasma testosterone: an accurate monitor of hormone treatment in prostatic cancer". Br J Urol. 45 (6): 668–77. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.1973.tb12238.x. PMID 4359746.

- ^ a b Jordan VC, Mittal S, Gosden B, Koch R, Lieberman ME (September 1985). "Structure-activity relationships of estrogens". Environmental Health Perspectives. 61: 97–110. doi:10.1289/ehp.856197. PMC 1568776. PMID 3905383.

- ^ Vitamins and Hormones. Academic Press. 18 May 1976. pp. 387–. ISBN 978-0-08-086630-7.

- ^ Khan HN, Blamey RW (August 2003). "Endocrine treatment of physiological gynaecomastia". BMJ. 327 (7410): 301–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7410.301. PMC 1126712. PMID 12907471.

- ^ Duncan CJ, Kistner RW, Mansell H (October 1956). "Suppression of ovulation by trip-anisyl chloroethylene (TACE)". Obstet Gynecol. 8 (4): 399–407. PMID 13370006.

- ^ Avendano C, Menendez JC (11 June 2015). Medicinal Chemistry of Anticancer Drugs. Elsevier Science. pp. 87–. ISBN 978-0-444-62667-7.

- ^ Manni A (15 January 1999). Endocrinology of Breast Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 286–287. ISBN 978-1-59259-699-7.

- ^ Ravina E (11 January 2011). The Evolution of Drug Discovery: From Traditional Medicines to Modern Drugs. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 178–. ISBN 978-3-527-32669-3.