Gliclazide

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Diamicron, Diaprel, Azukon, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 10.4 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.040.221 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

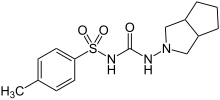

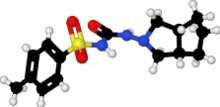

| Formula | C15H21N3O3S |

| Molar mass | 323.41 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 180 to 182 °C (356 to 360 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Gliclazide, sold under the brand name Diamicron among others, is a sulfonylurea type of anti-diabetic medication, used to treat type 2 diabetes.[7] It is used when dietary changes, exercise, and weight loss are not enough.[4] It is taken by mouth.[7]

Side effect may include low blood sugar, vomiting, abdominal pain, rash, and liver problems.[4][7] Use by those with significant kidney problems or liver problems or who are pregnant is not recommended.[7][4] Gliclazide is in the sulfonylurea family of medications.[7] It works mostly by increasing the release of insulin.[7]

Gliclazide was patented in 1966 and approved for medical use in 1972.[8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[9] It is not available for sale in the United States.[10]

Medical uses

[edit]Gliclazide is used for control of hyperglycemia in gliclazide-responsive diabetes mellitus of stable, mild, non-ketosis prone, type 2 diabetes. It is used when diabetes cannot be controlled by proper dietary management and exercise and when metformin has already been tried.[11]

National Kidney Foundation (2012 Update) claims that Gliclazide does not require dosage up titration even in end stage kidney disease.

Contraindications

[edit]- Type 1 diabetes[12]

- Hypersensitivity to sulfonylureas[12]

- Severe renal or hepatic failure[12] (But relatively useful in mild renal impairment e.g. CKD stage 3)

- Pregnancy and lactation[12]

Adverse effects

[edit]Common adverse effects over 10%:[13]

- Hypoglycemia (11 - 12%) - while it was shown to have the same efficacy as glimepiride, one of the newer sulfonylureas, the European GUIDE study has shown that it has approximately 50% less hypoglycemic confirmed episodes in comparison with glimepiride.[14]

Uncommon adverse effect between 1 - 10%:[13]

- Hypertension (3 - 4% incidence)

- Dizziness (2% incidence)

- Hyperglycemia (2% incidence)

- Viral infection (6 - 8% incidence)

- Back pain (4 - 5% incidence)

Rare adverse effects (under 1%):[13]

- cystitis

- weight gain

- Vomiting

Interactions

[edit]Hyperglycemic action may be caused by danazol, chlorpromazine, glucocorticoids, progestogens, or β-2 agonists. Its hypoglycemic action may be potentiated by phenylbutazone, alcohol, fluconazole, β-blockers, and possibly ACE inhibitors. It has been found that rifampin increases gliclazide metabolism in humans in vivo.[15]

Overdose

[edit]Gliclazide overdose may cause severe hypoglycemia, requiring urgent administration of glucose by IV and Monitoring.[16]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Gliclazide selectively binds to sulfonylurea receptors (SUR-1) on the surface of the pancreatic beta-cells. It was shown to provide cardiovascular protection as it does not bind to sulfonylurea receptors (SUR-2A) in the heart.[17] This binding effectively closes these K+ ion channels. This decreases the efflux of potassium from the cell which leads to the depolarization of the cell. This causes voltage dependent Ca2+ ion channels to open increasing the Ca2+ influx. The calcium can then bind to and activate calmodulin which in turn leads to exocytosis of insulin vesicles leading to insulin release.[18]

The mouse model of Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) diabetes suggested that the reduced gliclazide clearance stands behind their therapeutic success in human MODY patients, but Urbanova et al. found that human MODY patients respond differently and that there was no consistent decrease in gliclazide clearance in randomly selected HNF1A-MODY and HNF4A-MODY patients.[19]

Its classification has been ambiguous, as literature uses it as both a first-generation[20] and second-generation[21] sulfonylurea.

Properties

[edit]According to the Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS), gliclazide falls under the BCS Class II drug, which is poorly soluble and highly permeable.

Water solubility = 0.027mg/L[citation needed]

- Hypoglycemic sulfonylurea, restoring first peak of insulin secretion, increasing insulin Sensitivity.[22]

- No active circulating Metabolites.[13]

Metabolism

[edit]Gliclazide undergoes extensive metabolism to several inactive metabolites in human beings, mainly methylhydroxygliclazide and carboxygliclazide. CYP2C9 is involved in the formation of hydroxygliclazide in human liver microsomes and in a panel of recombinant human P450s in vitro.[23][24] But the pharmacokinetics of gliclazide MR are affected mainly by CYP2C19 genetic polymorphism instead of CYP2C9 genetic polymorphism.[25][26]

References

[edit]- ^ "Gliclazide - Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ "Gliclazide GH MR, Gliclazide LAPL MR, Gliclazide Lupin MR (Lupin Australia Pty Limited)". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 5 December 2022. Archived from the original on 18 March 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ "Product monograph brand safety updates". Health Canada. 7 July 2016. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Gliclazide Accord-UK 30mg Prolonged-release Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 12 February 2021. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ "Diamicron 30 mg MR Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 11 May 2020. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ "Dacadis MR 30mg Modified Release Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 15 July 2020. Archived from the original on 8 November 2023. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f British National Formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 474. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 449. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "Gliclazide Advanced Patient Information - Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ "My Site - Special Article: Remission of Type 2 Diabetes". guidelines.diabetes.ca. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d "GLICLAZIDE 60 MG MR TABLETS DRUG LEAFLET". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Gliclazide". Lexicomp. Wolters Kluwer N.V. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ Schernthaner G, Grimaldi A, Di Mario U, Drzewoski J, Kempler P, Kvapil M, et al. (August 2004). "GUIDE study: double-blind comparison of once-daily gliclazide MR and glimepiride in type 2 diabetic patients". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 34 (8): 535–542. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2004.01381.x. hdl:1874/10657. PMID 15305887. S2CID 13636359.

- ^ Park JY, Kim KA, Park PW, Park CW, Shin JG (October 2003). "Effect of rifampin on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of gliclazide". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 74 (4): 334–340. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00221-2. PMID 14534520. S2CID 21519151.

- ^ Mégarbane B, Chevillard L, Khoudour N, Declèves X (April 2022). "Gliclazide disposition in overdose - a case report with pharmacokinetic modeling". Clinical Toxicology. 60 (4): 541–542. doi:10.1080/15563650.2021.1993245. PMID 34698608. S2CID 239887850.

- ^ Lawrence CL, Proks P, Rodrigo GC, Jones P, Hayabuchi Y, Standen NB, Ashcroft FM (August 2001). "Gliclazide produces high-affinity block of KATP channels in mouse isolated pancreatic beta cells but not rat heart or arterial smooth muscle cells". Diabetologia. 44 (8): 1019–1025. doi:10.1007/s001250100595. PMID 11484080.

- ^ Mégarbane B, Chevillard L, Khoudour N, Declèves X (April 2022). "Gliclazide disposition in overdose - a case report with pharmacokinetic modeling". Clinical Toxicology. 60 (4): 541–542. doi:10.1080/15563650.2021.1993245. PMID 34698608. S2CID 239887850.

- ^ Urbanova J, Andel M, Potockova J, Klima J, Macek J, Ptacek P, et al. (2015). "Half-Life of Sulfonylureas in HNF1A and HNF4A Human MODY Patients is not Prolonged as Suggested by the Mouse Hnf1a(-/-) Model". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 21 (39): 5736–5748. doi:10.2174/1381612821666151008124036. PMID 26446475.

- ^ Ballagi-Pordány G, Köszeghy A, Koltai MZ, Aranyi Z, Pogátsa G (January 1990). "Divergent cardiac effects of the first and second generation hypoglycemic sulfonylurea compounds". Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 8 (2): 109–114. doi:10.1016/0168-8227(90)90020-T. PMID 2106423.

- ^ Shimoyama T, Yamaguchi S, Takahashi K, Katsuta H, Ito E, Seki H, et al. (June 2006). "Gliclazide protects 3T3L1 adipocytes against insulin resistance induced by hydrogen peroxide with restoration of GLUT4 translocation". Metabolism. 55 (6): 722–730. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2006.01.019. PMID 16713429.

- ^ Mégarbane B, Chevillard L, Khoudour N, Declèves X (April 2022). "Gliclazide disposition in overdose - a case report with pharmacokinetic modeling". Clinical Toxicology. 60 (4): 541–542. doi:10.1080/15563650.2021.1993245. PMID 34698608. S2CID 239887850.

- ^ Rieutord A, Stupans I, Shenfield GM, Gross AS (December 1995). "Gliclazide hydroxylation by rat liver microsomes". Xenobiotica; the Fate of Foreign Compounds in Biological Systems. 25 (12): 1345–1354. doi:10.3109/00498259509061922. PMID 8719909.

- ^ Elliot DJ, Lewis BC, Gillam EM, Birkett DJ, Gross AS, Miners JO (October 2007). "Identification of the human cytochromes P450 catalysing the rate-limiting pathways of gliclazide elimination". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 64 (4): 450–457. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02943.x. PMC 2048545. PMID 17517049.

- ^ Zhang Y, Si D, Chen X, Lin N, Guo Y, Zhou H, Zhong D (July 2007). "Influence of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms on pharmacokinetics of gliclazide MR in Chinese subjects". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 64 (1): 67–74. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02846.x. PMC 2000619. PMID 17298483.

- ^ Xu H, Williams KM, Liauw WS, Murray M, Day RO, McLachlan AJ (April 2008). "Effects of St John's wort and CYP2C9 genotype on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of gliclazide". British Journal of Pharmacology. 153 (7): 1579–1586. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707685. PMC 2437900. PMID 18204476.