Imipenem

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Primaxin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| MedlinePlus | a686013 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | IM, IV |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 20% |

| Metabolism | Renal |

| Elimination half-life | 38 minutes (children), 60 minutes (adults) |

| Excretion | Urine (70%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.058.831 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

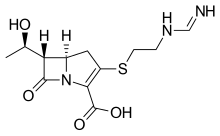

| Formula | C12H17N3O4S |

| Molar mass | 299.35 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Imipenem (trade name Primaxin among others) is a synthetic β-lactam antibiotic belonging to the carbapenems chemical class. developed by Merck scientists Burton Christensen, William Leanza, and Kenneth Wildonger in the mid-1970s.[1] Carbapenems are highly resistant to the β-lactamase enzymes produced by many multiple drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria,[2] thus playing a key role in the treatment of infections not readily treated with other antibiotics.[3] It is usually administered through intravenous injection.

Imipenem was patented in 1975 and approved for medical use in 1985.[4] It was developed via a lengthy trial-and-error search for a more stable version of the natural product thienamycin, which is produced by the bacterium Streptomyces cattleya. Thienamycin has antibacterial activity, but is unstable in aqueous solution, thus it is practically of no medicinal use.[5] Imipenem has a broad spectrum of activity against aerobic and anaerobic, Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.[6] It is particularly important for its activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus species. However, it is not active against MRSA.

Medical uses

[edit]Spectrum of bacterial susceptibility and resistance

[edit]Acinetobacter anitratus, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, Actinomyces odontolyticus, Aeromonas hydrophila, Bacteroides distasonis, Bacteroides uniformis, and Clostridium perfringens are generally susceptible to imipenem, while Acinetobacter baumannii, some Acinetobacter spp., Bacteroides fragilis, and Enterococcus faecalis have developed resistance to imipenem to varying degrees. Not many species are resistant to imipenem except Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Oman) and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia.[7]

Coadministration with cilastatin

[edit]Imipenem is rapidly degraded by the renal enzyme dehydropeptidase 1 when administered alone, and is almost always coadministered with cilastatin to prevent this inactivation.[8]

Adverse effects

[edit]Common adverse drug reactions are nausea and vomiting. People who are allergic to penicillin and other β-lactam antibiotics should take caution if taking imipenem, as cross-reactivity rates are high. At high doses, imipenem is seizurogenic.[9]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Imipenem acts as an antimicrobial through inhibiting cell wall synthesis of various Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. It remains very stable in the presence of β-lactamase (both penicillinase and cephalosporinase) produced by some bacteria, and is a strong inhibitor of β-lactamases from some Gram-negative bacteria that are resistant to most β-lactam antibiotics.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ U.S. patent 4,194,047

- ^ Clissold SP, Todd PA, Campoli-Richards DM (March 1987). "Imipenem/cilastatin. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy". Drugs. 33 (3): 183–241. doi:10.2165/00003495-198733030-00001. PMID 3552595. S2CID 209144637.

- ^ Vardakas KZ, Tansarli GS, Rafailidis PI, Falagas ME (December 2012). "Carbapenems versus alternative antibiotics for the treatment of bacteraemia due to Enterobacteriaceae producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 67 (12): 2793–803. doi:10.1093/jac/dks301. PMID 22915465.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 497. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ^ Kahan FM, Kropp H, Sundelof JG, Birnbaum J (December 1983). "Thienamycin: development of imipenen-cilastatin". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 12 Suppl D: 1–35. doi:10.1093/jac/12.suppl_d.1. PMID 6365872.

- ^ Kesado T, Hashizume T, Asahi Y (June 1980). "Antibacterial activities of a new stabilized thienamycin, N-formimidoyl thienamycin, in comparison with other antibiotics". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 17 (6): 912–7. doi:10.1128/aac.17.6.912. PMC 283902. PMID 6931548.

- ^ "Imipenem spectrum of bacterial susceptibility and Resistance" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ "Imipenem-Cilastatin". LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 17 January 2017. PMID 31644018. NBK548708. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Cannon JP, Lee TA, Clark NM, Setlak P, Grim SA (August 2014). "The risk of seizures among the carbapenems: a meta-analysis". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 69 (8): 2043–55. doi:10.1093/jac/dku111. PMID 24744302.

Further reading

[edit]- Clissold SP, Todd PA, Campoli-Richards DM (March 1987). "Imipenem/cilastatin. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy". Drugs. 33 (3): 183–241. doi:10.2165/00003495-198733030-00001. PMID 3552595. S2CID 209144637. Archived from the original on 2011-09-17. Retrieved 2011-03-21.

- Buckley MM, Brogden RN, Barradell LB, Goa KL (September 1992). "Imipenem/cilastatin. A reappraisal of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy". Drugs. 44 (3): 408–44. doi:10.2165/00003495-199244030-00008. PMID 1382937. S2CID 209143174. Archived from the original on 2012-04-06. Retrieved 2011-03-21.

External links

[edit]- "Imipenem". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.