Kvass

A mug of mint kvass and its ingredients | |||||||

| Alternative names | kvas, quass, quasse, quas, quash, kuass, kwas, gira | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Fermented low-alcoholic beverage | ||||||

| Course | Beverage | ||||||

| Region or state | Northeastern Europe; Central and Eastern Europe; North Caucasus; Xinjiang, China; Heilongjiang, China | ||||||

| Associated cuisine | Slavic (Belarusian, Polish,[1] Russian,[2][3][4] and Ukrainian), Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian and Uyghur cuisine | ||||||

| Serving temperature | Cold or room temperature | ||||||

| Main ingredients | Rye bread or rye flour and rye malt, as well as water and yeast | ||||||

| Ingredients generally used | Berries, fruits, herbs, honey | ||||||

| Variations | Beetroot kvass,[5] white kvass[6] | ||||||

| Circa 30–100 kcal | |||||||

| |||||||

Kvass is a fermented, cereal-based, low-alcoholic beverage of cloudy appearance and sweet-sour taste.

Kvass originates from northeastern Europe, where grain production was considered insufficient for beer to become a daily drink. The first written mention of kvass is found in Primary Chronicle, describing the celebration of Vladimir the Great's[8][9] baptism in 988.[10] In the traditional method, kvass is made from a mash obtained from rye bread or rye flour and malt soaked in hot water, fermented for about 12 hours with the help of sugar and bread yeast or baker's yeast at room temperature. In industrial methods, kvass is produced from wort concentrate combined with various grain mixtures. It is a popular drink in Poland,[11][12] Russia,[13][3] Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Moldova, as well as some parts of Finland, Sweden, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and China.

Terminology

[edit]The word kvass is ultimately from Proto-Indo-European base *kwh₂et- ('to become sour').[14] In English it was first mentioned in a text around 1553 as quass.[15][16] Nowadays, the name of the drink is almost the same in most languages: in Polish: kwas chlebowy (lit. 'bread kvass', to differentiate it from kwas, 'acid', originally from kwaśny, 'sour'); Belarusian: квас, kvas; Russian: квас, kvas; Ukrainian: квас/хлібний квас/сирівець, kvas/khlibny kvas/syrivets; Latvian: kvass; Romanian: cvas; Hungarian: kvasz; Serbian: квас/kvas; Chinese: 格瓦斯/克瓦斯, géwǎsī/kèwǎsī; Eastern Finnish: vaasa. Non-cognates include Estonian kali, Finnish kalja, Latvian dzersis (lit. 'beverage'), Latgalian dzyra (lit. 'beverage', similar to Lithuanian gira), Lithuanian gira (lit. 'beverage', similar to Latvian dzira), and Swedish bröddricka (lit. 'bread drink').

Production

[edit]

In the traditional method, either dried rye bread or a combination of rye flour and rye malt is used. The dried rye bread is extracted with hot water and incubated for 12 hours at room temperature, after which bread yeast and sugar are added to the extract and fermented for 12 hours at 20 °C (293 K; 68 °F). Alternatively, rye flour is boiled, mixed with rye malt, sugar, and baker's yeast and then fermented for 12 hours at 20 °C (293 K; 68 °F).[5]

The simplest industrial method produces kvass from a wort concentrate. The concentrate is warmed up and mixed with a water and sugar solution to create wort with a sugar concentration of 5–7% and pasteurized to stabilize it. After that, the wort is pumped into a fermentation tank, where baker's yeast and lactic acid bacteria culture is added, and the solution is fermented for 12–24 hours at 12 to 30 °C (285 to 303 K; 54 to 86 °F). Only around 1% of the extract is fermented out into ethanol, carbon dioxide, and lactic acid. Afterwards, the kvass is cooled to 6 °C (279 K; 43 °F), clarified through either filtration or centrifugation, and adjusted for sugar content, if necessary.[17]

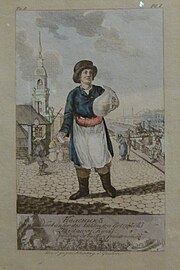

Initially, it was filled in large containers from which the kvass was sold on streets, but now, the vast majority of industrially produced kvass is filled and sold in 1–3-litre plastic bottles and has a shelf life of 4–6 weeks.[18]

Kvass is usually 0.5–1.0% alcohol by weight,[19][20] but may sometimes be as high as 2.0%.[21]

History

[edit]

The exact origins of kvass are unclear, and whether it was invented by Slavic people or any other Eastern European ethnicity is unknown,[22] although some Polish sources claim that kvass was invented by Slavs.[23][21] Kvass has existed in the northeastern part of Europe, where grain production is thought to have been insufficient for beer to become a daily drink.[22] It has been known among the Early Slavs since the 10th century.[23][21] Likely invented in the Kievan Rus' and known there since at least the 10th century, kvass has become one of the symbols of East Slavic cuisine.[21] The first written mention of kvass is found in the Primary Chronicle, describing the celebration of Vladimir the Great's baptism in 988, when kvass along with mead and food was given out to the citizens of Kiev.[24] Kvass-making remained a daily household activity well into the 19th century.[17]

In the second half of the 19th century, with military engagement, increasing industrialization, and large-scale projects, such as the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway creating a growing need to supply large numbers of people with foodstuff for extended periods of time, kvass became commercialized; more than 150 kvass varieties, such as apple, pear, mint, lemon, chicory, raspberry, and cherry were recorded. As commercial kvass producers began selling it in barrels on the streets, domestic kvass-making started to decline.[17] For example, in the year ended 30 June 1912, there were 17 factories in the Governorate of Livonia, producing a total of 437,255 gallons of kvass.[25]

In the 1890s, the first scientific studies into the production of kvass were conducted in Kiev, and in the 1960s, commercial mass production technology of kvass was further developed by chemists in Moscow.[17]

By country

[edit]Russia

[edit]

Although the massive flood of western soft drinks after the fall of the USSR, such as Coca-Cola and Pepsi substantially shrank the market share of kvass in Russia, in recent years it has regained its original popularity, often marketed as a national soft drink or "patriotic" alternative to the famous Coca-Cola drink. For example, the Russian company Nikola has promoted its brand of kvass with an advertising campaign emphasizing "anti-cola-nisation." Moscow-based Business Analytica reported in 2008 that bottled kvass sales had tripled since 2005 and estimated that per capita kvass consumption in Russia would reach three litres in 2008. Between 2005 and 2007, cola's share of the Moscow soft drink market fell from 37% to 32%. Meanwhile, kvass's share more than doubled over the same time period, reaching 16% in 2007. In response, Coca-Cola launched its own brand of kvass in May 2008. This is the first time a foreign company has made an appreciable entrance into the Russian kvass market. Pepsi has also signed an agreement with a Russian kvass manufacturer to act as a distribution agent. The development of new technologies for storage and distribution, and heavy advertising, have contributed to this surge in popularity; three new major brands have been introduced since 2004.[26]

Market shares for Russia (2014)

| Company | Brand name | Share [%][27] |

|---|---|---|

| Deka | Никола | 39 |

| Ochakovo | Очаковский | 18.9 |

| PepsiCo | Русский дар | 11.6 |

| Carlsberg Group | Хлебный край | 5.5 |

| Coca-Cola, Inc. | Кружка и бочка | 2.1 |

| Other | 22.9 |

Belarus

[edit]

Belarus has several breweries producing kvass: Alivaria Brewery, Babrujski Brovar, and Krinitsa. It also has a variety of kvass tasting and entertainment festivals.[28] The largest show takes place in the city of Lida.[29]

-

Belarusian white kvass, produced by Alivaria Brewery (Minsk, 2022).

Poland

[edit]

Kvass may have appeared in Poland as early as the 10th century,[23] it quickly became a trendy beverage thanks to it easy and cheap method of production as well as its thirst-quenching and digestion-aiding qualities.[30] By the time of Władysław II Jagiełło's rule, kvass was universal.[21] It was at first commonly drunk by peasants in the eastern parts of the country, but eventually the drink spread to the szlachta.[21] One example of this is kwas chlebowy sapieżyński kodeński, an old type of Polish kvass that is still sold as a contemporary brand. Its origins can be traced back to the 1500s, when Jan Sapieha founded the town of Kodeń on land granted by the Polish king. He then bought the mills and 24 villages of the surrounding areas from their previous landowners. Then, the taste of kvass became known among the Polish szlachta, who used it for its supposed healing qualities. Throughout the 19th century, kvass remained popular among Poles who lived in the Congress Poland of Imperial Russia and in Austrian Galicia, especially the inhabitants of rural areas.[31] Up until the 19th century, recipes for local variants of kvass remained well-guarded secrets of families, religious orders, and monasteries.[32]

The beverage production in Poland on an industrial scale can be traced back to the more recent interwar period, when the Polish state regained independence as the Second Polish Republic. In interwar Poland, kvass was brewed and sold in mass numbers by magnates of the Polish drinks market like the Varsovian brewery Haberbusch i Schiele or the Karpiński company.[33] Kvass remained particularly popular in eastern Poland.[31] However, with the collapse of many prewar businesses and much of the Polish industry during World War II, kvass lost popularity following the aftermath of the war. It also gradually lost favour throughout the 20th century upon introducing mass-produced soft drinks and carbonated water into the Polish market.[34][23][21] In the early 21st century, kvass experienced a renaissance in Poland due to the heightened interest in healthy diets, natural products, and traditions.[23]

Kvass can be found in some supermarkets and grocery stores, where it is known in Polish as kwas chlebowy ([kvas xlɛbɔvɨ]). Commercial bottled versions of the drink are the most common variant, as some companies specialise in manufacturing a more modern version of the drink (some variants are manufactured in Poland whilst others are imported from its neighbouring countries, Lithuania and Ukraine being the most popular source).[35][36] However, old recipes for a traditional version of kvass exist. Some of them originate from eastern Poland;[37] others from more central regions include adding honey for flavour.[38] Although commercial kvass is much easier to find in Polish shops, Polish manufacturers of more natural and healthier variants of kvass have become increasingly popular both within and outside of the country's borders.[39][23] A less healthy alternative of quick-to-make variants using kvass concentrate can also be purchased in shops.[40] One colloquial Polish name for kwas chlebowy is wiejska oranżada ('rural orangeade').[21] In some Polish villages, such as Zaława and its surroundings, kvass was traditionally produced on every farm.[41]

Latvia

[edit]

In Latvian, kvass was also called dzersis.[42] After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the street vendors disappeared from the streets of Latvia due to new health laws that banned its sale on the street. Economic disruptions forced many kvass factories to close. The Coca-Cola Company moved in and began quickly dominating the soft drink market. In 1998, the local soft drink industry adapted by selling bottled kvass and launching aggressive marketing campaigns. This surge in sales was stimulated by the fact that kvass sold for about half the price of Coca-Cola. In just three years, kvass constituted as much as 30% of the soft drink market in Latvia, while the market share of Coca-Cola fell from 65% to 44%. The Coca-Cola Company had losses in Latvia of about $1 million in 1999 and 2000. Coca-Cola responded by purchasing kvass manufacturers and producing kvass at their own soft drink plants.[43][44]

On 30 September 2010, the Saeima (parliament) adopted quality and classification requirements for kvass, defining it as "a beverage obtained by fermenting a mixture of kvass wort with a yeast of microorganism cultures to which sugar and other food sources and food additives are added or not added after the fermentation" with a maximum ABV of 1.2 percent, and differentiating it from an unfermented non-alcoholic mixture of grain product extract, water, flavourings, preservatives, and other ingredients, which is designated as a "kvass (malt) beverage".[45]

In 2014, Latvian kvass producers won seven medals at the Russian Beverage exposition in Moscow, with Ilgezeem's Porter Tanheiser kvass winning two gold medals.[46] In 2019, Iļģuciema kvass ranked second in the Most Loved Latvian Beverage Brand Top,[47][unreliable source?] and first in the subsequent 2020 top.[48][unreliable source?]

Lithuania

[edit]In Lithuania, kvass is known as gira and is widely available in bottles and drafts. The first written records of kvass and kvass recipes in Lithuania appeared in the 16th century.[citation needed] Many restaurants in Vilnius make their own kvass, which they sell on the premises. Some brands of mass-produced Lithuanian kvass are also sold on the Polish market.[35] Strictly speaking, gira can be made from anything fermentable—such as caraway tea, beetroot juice, or berries—but it is made mainly from black bread, or barley or rye malt.

Estonia

[edit]

In Estonia, kvass is known as kali. Initially, it was made from either brewer's spent grain or wort left to ferment in a closed container, but later, special kvass bread (kaljaleib) or industrially produced malt concentrate started to be used. Nowadays, kali generally is industrially produced with the use of pasteurization, the addition of preservatives, and artificial carbonation.[49]

Finland

[edit]In Finland, a fermented drink made from a mixture of rye flour and rye malt was ubiquitous in parts of Eastern Finland and was heated in the oven. It was called kalja (which can also be used to refer to small beer) or vaasa (in Eastern Finnish), while nowadays the drink is often known as kotikalja (lit. 'home kalja') and is available in many work canteens, gas stations, and lower-end restaurants.[22]

Traditionally, kalja was usually made in households once a week from a mixture of malted and unmalted rye grains. Other grains, such as oats or barley, were also sometimes used; occasionally, leftover potatoes or pieces of bread were added. Everything was mixed with water in a metal cauldron or a clay pot and kept warm in the oven or by the stove for at least six hours for the mixture to darken and sweeten. Sometimes, the grain solids were filtered out through lautering. In Eastern Finland, the mixture was formed into large loaves and briefly baked for the crust to turn brown. The porridge or pieces of the malt bread were mixed into a wooden cask with water and fermented for one or two days with a previous batch, a sourdough starter, spontaneously or in more recent times with commercial baker's yeast. In the early 20th century, with sugar becoming more readily available, it started replacing the malting process, and modern kalja is made from dark rye malt, sugar, and baker's yeast.[50]

Sweden

[edit]Kvass was also made in Sweden, where it was known as bröddricka (lit. 'bread drink'). However, it was very likely limited only to areas where rye bread was the standard bread as opposed to crispbread, which was more common in Western Sweden and did not go stale. Bröddricka was still being made in Öland farms up until 1935.[22]

China

[edit]

In the mid-19th century, kvass was introduced in Xinjiang, where it became known as kavas (Chinese: 格瓦斯; pinyin: géwǎsī) and eventually became one of the region's signature drinks.[51] It is usually consumed cold together with barbecue.[52] In 1900, Russian merchant Ivan Churin founded Harbin Churin Food (秋林 Qiulin) in Harbin, offering kvass and other specialities, and by 2009, the company was already producing 5,000 tons of kvass a year, making up 90% of the local market. In 2011, it moved its kvass factory to Tianjin, increasing its sales to 20,000 tons in the first year.[53]

Elsewhere

[edit]Following the influx of immigrants in the UK due to the 2004 enlargement of the European Union, several stores selling cuisine and beverages from Eastern Europe were established, many of which stock imported (primarily pasteurised) kvass. As a result, since then a number of different flavours of not-pasteurised kvass, fermented using sourdough starter culture, have also become available in the UK in 2023.[54] In recent years, kvass has also become more popular in Serbia.[55]

In 2017, a version of kvass from carrots or beets was developed in California by the producer Biotic Ferments.[56]

Nutritional composition

[edit]Naturally fermented kvass contains 5.9%±0.02 carbohydrates, of which 5.7%±0.02 are sugars (mostly fructose, glucose, and maltose), as well as 0.71±0.09, 1.28±0.12, and 18.14±0.48 mg/100 g of thiamine, riboflavin, and niacin respectively. In addition to that, 19 different aroma volatile compounds have also been identified in naturally fermented kvass, most notably 4-penten-2-ol (10.05×107 PAU), which has a fruity odour; carvone (2.28×107 PAU) originating from caraway fruits used as an ingredient in rye bread; and ethyl octanoate (1.03×107 PAU), which has an odour of fruit and fat.[7]

Traditional kvass made from rye wholemeal bread has been found to have, on average, twice the dietary fibre content, 60% more antioxidant activity (due to the addition of caramel and citric acid to the bread), and three times less reducing sugar content than industrially produced kvass.[57]

Historically, alcohol by volume (ABV) of kvass varied depending on the ingredients, microbial flora, as well as temperature and length of fermentation,[17] but nowadays it is usually not higher than 1.5%. The wide availability and consumption of kvass, including by children of all ages, together with the lacking indication of ABV for kvass on the labels and in advertisements, has been named a possible contributor to chronic alcoholism in the former Soviet Union.[58]

Use

[edit]Apart from drinking, kvass is also used by families as the basis for many dishes.[59] Traditional cold summertime soups of Russian cuisine, such as okroshka,[60] botvinya, and tyurya, are based on kvass.

Cultural references

[edit]

The name of Kvasir, a wise being in Norse mythology, is possibly related to kvass.[61][62][63][64][65]

There is a Russian expression, Перебиваться с хлеба на квас (literally 'to clamber from bread to kvass'), which means 'to live from hand to mouth' or to 'scrape by'[66] referring to the frugal practice amongst the poor peasants of making kvass from stale leftovers of rye bread.[67] Another kvass-related term in Russian is "kvass patriotism" (квасной патриотизм) dating back to an 1823 letter by the Russian poet Pyotr Vyazemsky who defined it as "unqualified praise of everything that is your own".[68]

In the Polish language, several traditional sayings that reference kwas chlebowy exist.[41] There is also an old Polish folk rhyming song. It shows the history of kvass in the country as having been drunk by generations of Polish reapers as a thirst-quenching beverage used during periods of hard work during the harvest season, long before it became popular as a medicinal drink among the szlachta. The song goes as follows:[69]

| Original Polish lyrics | English translation |

|---|---|

Od dawien dawna słynie napój zdrowy: |

A healthy drink has long been renowned: |

In the Polish village of Zaława, there is a customary game known as wulkan ('volcano') that is associated with the beverage. The fermentation of sugars makes kvass slightly carbonated, thus, when shaken or heated, it can cause the liquid to suddenly and rapidly rise out of an open vessel. Playing wulkan consists of vigorously shaking a bottle of kvass shortly before handing it to someone else who is going to drink it; the sudden "shooting out" of the beverage onto the person opening the bottle is a source of entertainment for the youth of Zaława and a well-known prank during regional festivities.[41]

In Tolstoy's War and Peace, French soldiers are aware of kvass on entering Moscow, enjoying it but referring to it as "pig's lemonade".[70] In Sholem Aleichem's Motl, Peysi the Cantor's Son, diluted kvass is the focus of one of Motl's older brother's get-rich-quick schemes.[71]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Co warto wiedzieć o kwasie chlebowym" (in Polish). WP Kuchnia. 8 January 2016. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ "Kvas Patriotism in Russia: Cultural Problems, Cultural Myths". NYU Jordan Center. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ a b "A brief history of Kvass, Russia's 'bread in a bottle'". Russia Beyond. 23 August 2021. Archived from the original on 30 November 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ "История кваса и его полезные свойства" (in Russian). Сергиев Канон. Archived from the original on 30 November 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ a b Amaresan, Natarajan; Ayyadurai, Sankaranarayanan; Dhanasekaran, Dharumadurai, eds. (2020). Fermented Food Products. Taylor & Francis. pp. 287–292. ISBN 978-0-367-22422-6.

- ^ Tarasevich, Grigory (5 September 2013). "White kvass: An old drink with a new taste". Russia Beyond. Archived from the original on 20 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d Līdums, Ivo; Kārkliņa, Daina; Ķirse, Asnate; Šabovics, Mārtiņš (April 2017). "Nutritional value, vitamins, sugars and aroma volatiles in naturally fermented and dry kvass" (PDF). Foodbalt. Faculty of Food Technology, Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies: 61–65. doi:10.22616/foodbalt.2017.027. ISSN 2501-0190. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ "Vladimir the Great: From Pagan Philanderer to Christian Saint". Dance's Historical Miscellany. 8 April 2014. Archived from the original on 30 November 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ "Vladimir Adopts Christianity". Christian History Institute. Archived from the original on 5 December 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ "Павел Сюткин: Квас без прикрас – правда и мифы о традиционном русском напитке" (in Russian). Российский Союз Потребителей (Росконтроль). Archived from the original on 30 November 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ "Co warto wiedzieć o kwasie chlebowym" (in Polish). WP Kuchnia. 8 January 2016. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ "Kwas chlebowy i jego znaczenie dla zdrowia. Przepis na kwas chlebowy" (in Polish). Medonet. 19 December 2022. Archived from the original on 30 November 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ "История кваса и его полезные свойства" (in Russian). Сергиев Канон. Archived from the original on 30 November 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ "Palaeolexicon – The Proto-Indo-European word *kwat-". palaeolexicon.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ "kvass". Webster's Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ Kvass in Oxford English Dictionary. c 1553 Chancelour Bk. Emp. Russia in Hakluyt Voy. (1886) III. 51 Their drinke is like our peny Ale, and is called Quass.

- ^ a b c d e Hornsey, Ian Spencer (2012). Alcohol and its Role in the Evolution of Human Society. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 296–300. ISBN 978-1-84973-161-4.

- ^ Gobbetti, Marco; Gänzle, Michael, eds. (2013). Handbook on Sourdough Biotechnology. Springer Publishing. pp. 272–274. ISBN 978-1-4614-5424-3.

- ^ Hornsey, I.S. (2003). A History of Beer and Brewing. RSC paperbacks. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-85404-630-0. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

A similar, low alcohol (0.5–1.0%) drink, kvass… may be a 'fossil beer'

- ^ Dlusskaya, Elena; Jänsch, André; Schwab, Clarissa; Gänzle, Michael G. (1 May 2008). "Microbial and chemical analysis of a kvass fermentation". European Food Research and Technology. 227 (1): 261–266. doi:10.1007/s00217-007-0719-4. ISSN 1438-2385. S2CID 84724879.

The predominant carbohydrates are maltose, maltotriose, glucose, and fructose, the ethanol content is 1% or less [2]. Kvass is considered to be spoiled if ethanol accumulates to higher levels.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Snopkow, Paweł (23 October 2021). "Kwas chlebowy. Zapomniany skarb polskiej kuchni". gazetaolsztynska.pl. Gazeta Olsztyńska. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d Garshol, Lars Marius (2020). Historical Brewing Techniques: The Lost Art of Farmhouse Brewing. Brewers Publications. pp. 254–257. ISBN 978-1-938-46955-8.

Nobody knows who invented kvass, or when. The first written mention of it is in Nestor's Primary Chronicle, compiled in Kiev in the early twelfth century. At that time there was no Russia as we understand it today, and whether it was a Slavic people or some other eastern European ethnicity that invented kvass will probably never be known.

- ^ a b c d e f Mucha, Sławomir (3 June 2018). "Kwas chlebowy". Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of Poland. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ "The Early History of Kiev" (PDF). Princeton University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 November 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ Daily Consular and Trade Reports. Vol. 1. Washington: Government Printing Office. 1913. p. 114.

- ^ Russia's patriotic kvass drinkers say no to cola-nisation. The New Zealand Herald. BUSINESS; General. 12 July 2008. [dead link]

- ^ "Россия. Квас "Никола" стал маркой № 1 в продажах кваса по результатам летнего сезона". Пивное дело. 18 September 2014. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ Webb, Tim; Beaumont, Stephen (2016). World Atlas of Beer: THE ESSENTIAL NEW GUIDE TO THE BEERS OF THE WORLD. Hachette UK. p. 148. ISBN 9781784722524.

- ^ "Drinks in Belarus". belarus.by. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Wieczorek, K. (2006). Młyn na Stawkach. Nad Czarną. Lubiaszów.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Kwas chlebowy sapieżyński kodeński". Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of Poland. 2 July 2018. Archived from the original on 9 February 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Dekowski, J.P. (1968). "Z badań nad pożywieniem ludu łowickiego (1880-1939)". Seria Etnograficzna (12). Łódź.

- ^ Delorme, Andrzej (1–15 October 1999). "Alternatywa dla Coca Coli?". Pismo Ekologów (14(140)/99). Zielone Brygady. ISSN 1231-2126. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Historia kwasu chlebowego". kwaschlebowy.eu. Eko-Natura. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

W wieku XX kwas został zapomniany, wyparty przez wody gazowane i inne słodkie napoje.

- ^ a b Gerima dystrybutor kwasu chlebowego w Polsce Archived 16 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine Gerima – distributor of kvass in Poland. (in Polish)

- ^ "Kwas chlebowy z Ukrainy – dlaczego warto go kupić?". zdrowozmiksowani.pl. Zdrowo Zmiksowani. 22 October 2020. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ "Kwas chlebowy sapieżyński kodeński" [Sapieżyński Kodeński kvass]. lubelskie.pl (in Polish). Lublin Voivodeship. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013.

- ^ Mucha, Sławomir (25 January 2019). "Kwas chlebowy na miodzie z Grębkowa". Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of Poland. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ Jeziorska, Jolanta (8 September 2009). "Ich kwas chlebowy podbija rynek" [Their kvass conquers the market]. Dziennik Łódzki (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ S. Orgelbranda Encyklopedja Powszechna. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Towarzystwa Akcyjnego Odlewni Czcionek i Drukarni S. Orgelbranda Synów. 1901.

- ^ a b c "Kwas chlebowy z Załawy". Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of Poland. 10 April 2020. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ "What and How Latvians Used to Eat. Acorn Coffee, Beer, Sugar and Sweets". Latvia Eats. 11 March 2021. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Lyons, J. Michael (31 March 2002). "Soviet Brew Is Back, This Time, in Bottles". The Washington Post. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Smith, Benjamin (7 September 2002). "In Latvia, Forces of Globalism Ferment Market for Traditional Soft-Drink Brew". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Quality and Classification Requirements for Kvass and Kvass (Malt) Beverage". likumi.lv. Archived from the original on 29 December 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Latvian kvass takes awards at Moscow beverage expo". Public Broadcasting of Latvia. 1 September 2014. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Iļģuciema kvass won the 2nd place in The Latvia's Most Loved Drink top". Ilgezeem. 9 October 2019. Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Iļģuciema kvass won 1st place in the Most Loved Latvian Beverage Brand top!". Ilgezeem. 21 October 2020. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Sõukand, Renata; Kalle, Raivo (2016). Changes in the Use of Wild Food Plants in Estonia 18th – 21st Century. Springer Publishing. p. 98. ISBN 978-3-319-33949-8.

- ^ Laitinen, Mika; Mosher, Randy (2019). Viking Age Brew: The Craft of Brewing Sahti Farmhouse Ale. Chicago Review Press. pp. 98–104. ISBN 978-1-641-60047-7.

- ^ "Xinjiang native beer-kvass". INFNews. 22 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Yike, Wang (22 February 2018). "Beverages of Xinjiang". Youlin Magazine. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ "Chinese Thirst for Kvass Draws Wahaha into Russian Niche". Goldsea. 15 April 2013. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Puzorjov, Anton. "The Genuine Kvass: Benefits, Varieties and Comparison With Other Drinks". Quas Drinks. Archived from the original on 10 December 2023. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Bills, John William (12 November 2017). "Here's What to Drink if You're Going to Serbia". Culture Trip. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ "Why Kvass?". Biotic Ferments. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ Gambuś, Halina; Mickowska, Barbara; Barton, Henryk J.; Augustyn, Grażyna (February 2015). "Health benefits of kvass manufactured from rye wholemeal bread". Journal of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Food Sciences. 4 (3 (special issue)). Slovak University of Agriculture: 34–39. doi:10.15414/jmbfs.2015.4.special3.34-39. ISSN 1338-5178.

- ^ Jargin, Sergei V. (September–October 2009). "Kvass: A Possible Contributor to Chronic Alcoholism in the Former Soviet Union—Alcohol Content Should Be Indicated on Labels and in Advertising". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 44 (5): 529. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agp055. PMID 19734161.

- ^ Mucha, Sławomir (10 October 2018). "Kwas chlebowy". Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of Poland. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Katz, Sandor (2003). Wild Fermentation: The Flavor, Nutrition, and Craft of Live-Culture Foods. White River Junction, VA: Chelsea Green. p. 121. ISBN 1-931498-23-7.

- ^ Александр Николаевич Афанасьев (1865–1869). Поэтические воззрения славян на природу. Директ-медиа (2014) том. 1, стр. 260. ISBN 978-5-4458-9827-6 (Alexander Afanasyev. The Poetic Outlook of Slavs about Nature, 1865–1869; reprinted 2014, p. 260; in Russian)

- ^ Karl Joseph Simrock. Handbuch der deutschen Mythologie mit Einschluss der nordischen, 1st edition (1855), p. 272 or 2nd edition (1864), p. 244 Archived 28 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Bonn, Marcus.

- ^ Jooseppi Julius Mikkola. Bidrag till belysning af slaviska lånord i nordiska språk. Arkiv för nordisk filologi, vol. 19 (1903), p. 331 Archived 16 June 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Georges Dumézil (1974). Gods of the Ancient Northmen, p. 21 Archived 30 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03507-2

- ^ Jan de Vries (2000). Altnordisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, p. 336 Archived 30 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine. 4th edition, Leiden (in German)

- ^ Lubensky, Sophia (2013). Russian-English Dictionary of Idioms (Revised ed.). Yale University Press. p. 695. ISBN 9780300162271.

- ^ Svyatoslav Loginov, "We Used to Bake Blini..." ("Бывало пекли блины...") Archived 4 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ Latour, Abby (29 October 2018). "Kvas Patriotism in Russia: Cultural Problems, Cultural Myths". Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ Śliwińska, Jolanta (29 June 2017). "Kwas chlebowy sapieżyński kodeński". Smakuj Lubelskie. Retrieved 22 December 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ War and Peace. Leo Tolstoy. Book 10, chapter 29, Pennsylvania State University translation.

- ^ Vered, Ronit (15 November 2012). "A Touch of Kvass". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.