Bowling alley

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (March 2018) |

A bowling alley (also known as a bowling center, bowling lounge, bowling arena, or historically bowling club) is a facility where the sport of bowling is played. It can be a dedicated facility or part of another, such as a clubhouse or dwelling house.

History

[edit]By the late 1830s in New York City, the Knickerbocker Hotel's bowling alley had opened, with three lanes.[2] Instead of wood, this indoor alley used clay for the bowling lane. By 1850, there were more than 400 bowling alleys in New York City, which earned it the title "bowling capital of North America". Because early versions of bowling were difficult and there were concerns about gambling, the sport faltered. Several cities in the United States regulated bowling due to its association with gambling.[3][4]

In the late 19th century, bowling was revived in many U.S. cities. Alleys were often located in saloon basements and provided a place for working-class men to meet, socialize, and drink alcohol. Bars were and still are a principal feature of bowling alleys. The sport remained popular during the Great Depression and, by 1939, there were 4,600 bowling alleys across the United States. New technology was implemented in alleys, including the 1952 introduction of automatic pinsetters (or pinspotters), which replaced pin boys who manually placed bowling pins.[3] Today, most bowling alley facilities are operated by Bowlero Corporation. [citation needed]

In 2015, over 70 million people bowled in the United States.[5]

-

Bowling alleys often had a negative image, as shown in this 1836 editorial portraying bowling alleys as "drunkeries" that were "visited by a set of as miserably profane, drunken, worthless chaps as can be found".[6]

-

The number of U.S. bowling centers has declined significantly, though not as steeply as the decline in league bowlers. Many modern bowling centers bring in additional revenue with "cosmic bowling" and more diverse entertainment.[8]

Modern day

[edit]

Bowling alleys contain long and narrow synthetic or wooden lanes.[9] The number of lanes inside a bowling alley is variable. The Inazawa Grand Bowl in Japan is the largest bowling alley in the world, with 116 lanes.[10]

Human pinsetters were used at bowling alleys to set up the pins, but modern ten-pin bowling alleys have automatic mechanical pinsetters.

Each lane has an overhead monitor/television screen to display bowling scores and a seating area and tables for dining and socializing.

With a decades-long decline in league participation, modern bowling alleys usually offer other games (often billiard tables, darts and arcade games) and may serve food or beverages, usually via vending machines or an integrated bar or restaurant. Pro shops and party rooms are common.

Effect of lane characteristics on the game

[edit]

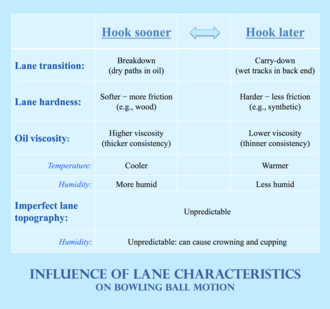

The phenomenon of lane transition occurs when balls remove oil from the lane as they pass, and deposit some of that oil on originally dry parts of the lane.[11][15] The process of oil removal, commonly called breakdown, forms dry paths that subsequently cause balls to experience increased friction and to hook sooner.[11][15] Conversely, the process of oil deposition, commonly called carry down, occurs when balls form oil tracks in formerly dry areas, tracks that subsequently cause balls to experience less friction and delayed hook.[11][15] Balls tend to "roll out" (hook sooner but hook less) in response to breakdown, and, conversely, tend to skid longer (and hook later) in response to carry down—both resulting in light hits.[12] Breakdown is influenced by the oil absorption characteristics and rev rates of the balls that were previously rolled,[11] and carry down is mitigated by modern balls having substantial track flare.[12]

Lane materials with softer surfaces such as wood engage the ball with more friction and thus provide more hook potential, while harder surfaces like synthetic compositions provide less friction and thus provide less hook potential.[11]

Higher-viscosity lane oils (those with thicker consistency) engage balls with more friction and thus cause slower speeds and shorter length but provide more hook potential and reduced lane transition; conversely, lane oils of lower viscosity (thinner consistency) are more slippery and thus support greater speeds and length but offer less hook potential and allow faster lane transition.[11] Various factors influence an oil's native viscosity, including temperature (with higher temperatures causing the oil to be thinner) and humidity (variations of which can cause crowning and cupping of the lane surface).[11] Also, high humidity increases friction that reduces skid distance so the ball tends to hook sooner.[13]

The lanes' physical topography—hills and valleys that diverge from an ideal planar surface—can substantially and unpredictably affect ball motion, even if the lane is within permissible tolerances.[11]References

[edit]- ^ "Bowling" (PDF). Spalding's Athletic Library. Vol. 1, no. 3. New York: American Sports Publishing Company. December 1892. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2020.

- ^ a b "Communicated - Bowling Alleys". Morning Herald. New York. June 18, 1838. p. 5. (edition of New York Daily Herald) (clipping)

- ^ a b Steven A. Riess (26 March 2015). Sports in America from Colonial Times to the Twenty-First Century. Routledge. ISBN 9781317459477. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "The History of Bowling". bowlingballs.us. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ Goldsmith, Margie (November 28, 2016). "America's Coolest Bowling Alleys". Travel + Leisure. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ "Drunkeries". Fall River Monitor and Weekly Recorder. Fall River, Massachusetts, U.S. October 8, 1836. p. 2. (clipping)

- ^ "Evasions of Law". Logansport Telegraph. Logansport, Indiana, U.S. March 10, 1838. p. 1.

- ^ Data: Wayback Machine archives of USBC's bowl.com website. Links provided on Wikimedia's image page (2019-04-03 archive thereof)

- ^ Mautner, Rob. "Stop, Look, and Listen to the Lanes!". Bowling This Month. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ Guinness World Records confirms Inazawa Grand Bowl world's largest Bowling Center

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Freeman & Hatfield 2018, Chapter 14 ("Applying Your Tools").

- ^ a b c Freeman & Hatfield 2018, Chapter 16 ("Advanced Considerations").

- ^ a b "Bowling Lane Adjusting From Pair To Pair". BowlingBall.com (Bowlversity educational section). June 28, 2016. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Bowling Catalog E". Gutenberg.org. Narragansett Machine Company. 1895. Archived from the original on July 1, 2018. Project Gutenberg release date: June 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Changing Lane Oil Conditions". BowlingBall.com (Bowlversity educational section). 2015. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015.

Works cited

[edit]- Freeman, James; Hatfield, Ron (July 15, 2018). Bowling Beyond the Basics: What's Really Happening on the Lanes, and What You Can Do about It. BowlSmart. ISBN 978-1 73 241000 8.

Further reading

[edit]- Jackson, Emma. "Bowling together? Practices of belonging and becoming in a London ten-pin bowling league." Sociology 54.3 (2020): 518-533.

![Bowling alleys often had a negative image, as shown in this 1836 editorial portraying bowling alleys as "drunkeries" that were "visited by a set of as miserably profane, drunken, worthless chaps as can be found".[6]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/25/18361008_Drunkeries_-_bowling_alley_miserably_profane_chaps_-_Fall_River_Monitor_%28Massachusetts%29.jpg/170px-18361008_Drunkeries_-_bowling_alley_miserably_profane_chaps_-_Fall_River_Monitor_%28Massachusetts%29.jpg)

![An 1838 Indiana newspaper describes how ten-pin bowling was devised to evade a Baltimore statute prohibiting nine-pin bowling.[7]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e7/18380310_Evasions_of_Law_-_Logansport_Telegraph.png/170px-18380310_Evasions_of_Law_-_Logansport_Telegraph.png)

![To project a classy image, this 1838 New York newspaper ad for the Knickerbocker Hotel's three bowling alleys boasted "excellent accommodations" and appealed to "gentlemen to perform their ablutions".[2]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3e/18380618_Kickerbocker_Hotel_bowling_alleys_-_Morning_Herald_%28New_York%29.jpg/170px-18380618_Kickerbocker_Hotel_bowling_alleys_-_Morning_Herald_%28New_York%29.jpg)

![The number of U.S. bowling centers has declined significantly, though not as steeply as the decline in league bowlers. Many modern bowling centers bring in additional revenue with "cosmic bowling" and more diverse entertainment.[8]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e5/1997-_Bowling_centers%2C_league_members%2C_and_lanes_-_normalized.svg/170px-1997-_Bowling_centers%2C_league_members%2C_and_lanes_-_normalized.svg.png)