Bhojpur Kadim

Bhojpur Kadim

Bhojpur Kadīm | |

|---|---|

Village | |

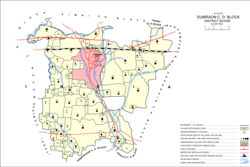

Map of Bhojpur Kadim (#116) in Dumraon block | |

| Coordinates: 25°35′03″N 84°07′36″E / 25.58409°N 84.12653°E[1] | |

| Country | India |

| State | Bihar |

| District | Buxar |

| Named for | Raja Bhoja |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.959 km2 (0.370 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 71 m (233 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

• Total | 18,243[2] |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Bhojpuri, Hindi |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

Bhojpur Kadim is a historic village in Dumraon block of Buxar district, Bihar, India. As of 2011, its population was 18,243, in 3,024 households.[2] Together with the neighboring Bhojpur Jadid, it lends its name to the surrounding Bhojpuri region.[3]

Name

[edit]The name Bhojpur is derived from the name of the Paramara dynasty king Bhoja, who reigned from Dhar and was a patron of the arts.[4] Kadim is an Urdu word meaning 'old'.[5] There is also the neighbouring village of Bhojpur Jadid, or New Bhojpur.[3]

History

[edit]Bhojpur was the capital of the Ujjainiya rajas of Bhojpur.[4] The Ujjainiyas, a Rajput clan that claimed ancestry from the Paramara dynasty that had ruled from Dhar and Ujjain,[4] migrated to the Bhojpur region sometime around 1320.[3] The founding figure, Sanatan[6] or Santana[7] Sahi, came to settle in the village of Karur in the pargana of Danwar at that time, while returning from a pilgrimage to Gaya.[7] Before this, the region was ruled by the Chero dynasty.[3] The region was heavily forested at that time, and the coming of the Ujjainiyas coincided with the clearing of much of this forest to make room for large-scale agriculture.[6]

Sanatan Sahi died around 1360 and was succeeded by his eldest son, Hunkar Sahi. Upon his accession, the Cheros under his rule revolted. Hunkar Sahi defeated them in a military campaign, with both sides taking heavy losses. One of the main Chero strongholds in the area was Bihiya, ruled by one Mahipaldev; Hunkar Sahi conquered Bihiya from him, and after this faced little opposition. He made Behea his capital and constructed new buildings there. Later generations would justify the conquest with a legend that Hunkar Sahi pledged devotion to the Muslim holy man Sharifuddin Maneri after witnessing one of his miracles; in turn, Sharifuddin Maneri declared Hunkar Sahi the rightful ruler of Bihiya.[6]

Hunkar Sahi died in 1410 and was succeeded by his son Dev Sahi, who was still a minor. As such, the boy's uncle, Ishwar Sahi, was appointed regent. Later, though, Dev Sahi reputedly went insane and was replaced by his younger brother Dullah Sahi, who moved his capital to Dawan[6] (or "Dawa"), in the pargana of Bihiya.[7] He died in 1484 at the age of 85 after a long reign. As his oldest son, Badal Sahi, was blind, a younger son ascended the throne as Ram Sahi. Ram Sahi continued to face opposition from the Chero tribes and attempted to impose social controls on them, banning them from arming themselves (except for hunting) and forbidding them from mingling with members of other tribes. His plan backfired — now the tribesmen turned to brigandage against the Ujjainiyas. Ram Sahi attempted to reestablish his rule by building thanas on the banks of the Karmanasa River, but to little effect.[6]

1500s

[edit]A clearer picture of the Bhojpur raj begins to emerge from the time of Raja Durlabh Deo, who ascended to the throne in 1489. This king had three wives and five sons: Badal Singh, Shivram Singh, Sangram Singh, Devendra Singh, and Mahipal Singh. In 1500, at the behest of his second wife, Durlabh Deo named Shivram Singh as his heir, which upset his other wives and sons. It was especially a snub to Badal Singh, the eldest son, who ended up leaving Bhojpur and venturing off in search of supporters. During this time, he met Farid Khan, the future Sher Shah Suri, who similarly had been driven from home. According to Bodhraj of Pugal, the two men became close friends and pledged to come to the other's assistance if he ever needed it. After Farid was given charge of Sasaram and Khawaspur Tanda in 1511, he helped restore Badal Singh to his aging father's good graces.[3]

Durlabh Deo died in 1519, and a bloody succession war broke out among his sons. Badal Singh and Mahipal Singh were both killed. Shivram Singh survived and became the sole ruler of Bhojpur, with his capital at Bihta. Later, in 1532, Badal Singh's widow met with Farid — now known as Sher Khan — and asked for assistance in raising her two sons (Gajpati Sahi, then 18, and Bairi Sal, then 15) to the throne. Sher Khan obliged and sent an army that, in 1534, defeated and killed Shivram Singh, and Gajpati Sahi became raja, with his seat at Jagdishpur.[3]

After this, Gajpati became a close ally of Sher Khan. In 1534, Sher Khan asked for Gajpati's assistance against Ghiyasuddin Mahmud Shah, the Sultan of Bengal, and Gajpati responded by mustering an army including 2,000 cavalrymen to aid him. At Surajgarh, their combined forces defeated those of the Sultan, with Gajpati killing the Sultan's commander Ibrahim Khan, and they seized the Bengal army's camp equipment, elephants, and artillery. Sher Khan, highly pleased, granted Gajpati the region of Buxar, and gave a sword to his younger brother, Bairi Sal.[3]

Meanwhile, the widow of Mahipal Singh, the other son of Durlabh Deo who had died in the 1519 succession war, sought assistance in raising her own son, Dalpati Sahi (aka Dalpat), to the Ujjainiya throne. She approached her brother Birbhan, of the pargana of Arail, Allahabad in the Allahabad Subah; he then in turn went to Humayun, the second Mughal emperor and a deep-seated rival of Sher Khan. In 1538, while Humayun was en route to Barkhnada in modern Palamau district, Birbhan met with him and Humayun agreed to provide him with troops. Birbhan was thus able to defeat Gajpati and install Dalpat on the throne in Jagdishpur.[3]

Indebted to Humayun, as Gajpati had been to Sher Khan, Birbhan sided with Humayun in his war against Sher Khan. After Humayun was defeated in the decisive Battle of Chausa against Sher Khan in 1539, Birbhan met with him and offered provisions. He helped Humayun escape pursuit by Sher Khan's general, Mir Farid Gaur, by crossing the Ganges near Mirzapur.[3]

In the meantime, the dispossessed Gajpati had again joined forces with Sher Khan, bringing a contingent of his own troops to the Battle of Chausa. He probably played a significant role in the battle, although later Ujjainiya sources say nothing about the matter. Not long after, he attacked Bhojpur, apparently with Sher Khan's assistance, and overthrew Dalpat as ruler of Bhojpur. In addition, Sher Khan granted Gajpati the title of Raja as well as rule over the sarkars of Rohtas and Shahabad. Finally, Gajpati built a fortress at his capital of Jagdishpur.[3]

Under the Sur Empire that was established after Sher Shah's victory at Chausa, Bhojpur was at peace. Gajpati was able to consolidate his rule, expanding as far as the border of the sarkar of Jaunpur. By this point, he was the most powerful chief in northwestern Bihar. After Humayun's victory at the Battle of Sirhind in 1555 led to the downfall of the short-lived Sur Empire and the reestablishment of Mughal power in northern India, there was a possibility that the overthrown Dalpat would seek Humayun's assistance in retaking Bhojpur, but Humayun's sudden death after falling down a staircase prevented such an occurrence.[3]

Under Humayun's successor Akbar, Gajpati originally resisted Mughal power but later, in 1568–69, he submitted to Munim Khan, the governor of Jaunpur, and agreed to pay 500,000 rupees per year as malguzari. In early 1573, Munim Khan appointed Gajpati to a military command against the Bengal Sultan Daud Khan Karrani. A year later, Gajpati accompanied Akbar in an attack on Hajipur, but as soon as 1576 he was openly in rebellion against Mughal rule. He was defeated in battle near Ghazipur and fled back to the forests of Bhojpur, while the Mughal army commandeered the fort of Moheda, about seven miles west of Bhojpur.[3] Then, in 1575,[6] they besieged Jagdishpur, where Gajpati had fled to. The siege lasted for three months before the fort surrendered, while Gajpati, along with his son Ram Singh and his brother Bairi Sal, escaped into the hilly forests nearby.[3]

Meanwhile, Dalpati Sahi, the son of Mahipal Singh who had briefly reigned in 1538-39 before being ousted by Gajpati, took advantage of the opportunity to press his claim. In 1577, he attacked Gajpati, who was killed in the following battle.[6] At about the same time, Bairi Sal was killed in a Mughal surprise attack. Ram Singh fled to the Shergarh Fort, but he soon surrendered to Shahbaz Khan.[3] Dalpati Sahi, now the sole Ujjainiya ruler, was recognized by Akbar with the title of Raja and restored to his former possessions. Akbar also made Dalpat a mansabdar. In return, Dalpat was to provide Akbar with military support. Dalpat moved his capital from Jagdishpur to Bihiya, although Jagdishpur remained his main military stronghold.[6]

However, as early as 1580, Dalpati had already revolted. He had joined an existing rebellion in Bihar and Bengal led by an Afghan named Arab Bahadur, who had besieged Patna. He moved his capital to Bahuara in Piro, where he built a fort called Dalpatgarh. Akbar appointed Mirza Aziz Koka as governor of Bihar in order to quell the rebellion. Arab Bahadur realised that his siege would not capture Patna before Mughal reinforcements arrived and fled to Bhojpur, where Dalpati Sahi granted him refuge and reaffirmed his commitment to fight against the Mughals. Now joined by Shahbaz Khan, the Mughal army under Aziz Koka sacked Jagdishpur, but the two rebels fled to the jungles. There, they adopted guerilla tactics and killed many Mughal soldiers. The Mughal commanders, Aziz Koka and Shahbaz Khan, fell out with each other at this point, and Aziz Koka later left to join Todar Mal. Shahbaz Khan ordered the jungles cleared in an attempt to force the rebels out into the open. Meanwhile, Dalpati Sahi and Arab Bahadur attacked the fort of Kant and killed its commander, Saadat Ali Khan. Upon hearing of this, Shahbaz Khan immediately marched towards Kant and forced the rebels to flee to Sasaram, where they were defeated. Arab Bahadur fled to Saran, where he continued to harass the area before moving again to Jaunpur to join the rebels of Masum Khan Farankhudi. However, Dalpat submitted to the Mughals.[3]

For eight years, Dalpat remained compliant before in 1599 rebelled again. Daniyal Mirza, who had been appointed governor of Allahabad, was sent to subdue him. When Daniyal reached Hajipur, Dalpat submitted and presented him with a gift of elephants, but soon again rebelled. He was, however, captured and pardoned; the Akbarnama says that Dalpat's daughter was married to Daniyal and in 1604 she had a son named Farhang Hushang. Meanwhile, Dalpat was murdered by his own kin in 1601.[3]

1600s

[edit]Upon Dalpat's death, his nephew Ram Sahi II assumed the throne, but Dalpat's son Mukutmani sought Akbar's assistance in becoming ruler instead. Mukutmani was physically very strong and impressed Akbar, who granted him the same mansab to as his father; Akbar presumably hoped to pit the two claimants against each other. After Akbar died in 1605, Mukutmani returned to Bhojpur to rule.[6] But he proved to be incompetent and unpopular, and in 1607 was forced to abdicate in favor of his nephew Narayan Mal.[3]

Narayan Mal then went to Agra and entered the service of Khurram, the future Shah Jahan. He didn't stay long, however — a major Chero uprising in 1607 prompted him to go back to Bhojpur. The Cheros of Bhojpur were assisted by the Chero rajas of Kaddhar, Anandichak, Balaunja, and Lohardaga, among others. Narayan Mal received the assistance of one Rai Kalyan Singh, who had been sent by Jahangir with a force of 500 cavalry to help him. The decisive battle of this conflict took place at Buxar. At first, the Cheros were on the verge of routing when a large allied force came to reinforce them. The Ujjainias then likewise came to the verge of routing before the Mughal cavalry arrived to reinforce them. Eventually, the Cheros fled the battlefield after a rumour that more Mughal reinforcements were coming spread. Afterwards, Narayan Mal was granted the title of Raja and a mansab of 1,000/800.[3]

Narayan Mal died in 1624 and was succeeded by his younger brother Pratap Singh, who was granted the title of Raja by Jahangir, along with a mansab of 1,000/8000 (later raised to 1,500/1,000 by Shah Jahan). Pratap Singh moved his capital from Jagdishpur to Bhojpur Kadim, where he built a palace called Navratna. He then held an official post in Agra for about a decade, after which he returned to Bhojpur. Not long after that, he fell out with the imperial administration, who accused him of exploiting the peasants. Then they found out that he had not paid revenue for the past 9 years, and demanded that he pay the full sum immediately as well as present himself before the emperor and explain his conduct. Raja Pratap at first complied, travelling as far as Ayodhya before changing his mind and openly rebelling against the emperor. Shah Jahan sent the governor of Bihar, Abdullah Khan Firoz Jung, and the governor of Allahabad, Baqar Khan Najm Sani, to quell the rebellion. He also sent Fidai Khan, the jagirdar of Gorakhpur, and Mukhtar Khan, the faujdar of Munger, to march on Bhojpur. The combined armies captured the forts at Tribaq and Kalur, along with several others, and laid siege to Bhojpur. The siege lasted for six months before Raja Pratap finally surrendered. He was arrested and sent to Patna, where he was executed, probably at the city's western gate.[3]

For a time thereafter, Bhojpur was under direct Mughal rule. Amar Singh, the son of Narayan Mal, had been passed over in 1624 when his uncle Pratap Singh had instead inherited the throne. He made an appeal to the governor of Bihar that he should be restored to the throne, but was denied. However, after seeking the assistance of Shah Shuja, then the governor of Bengal, he succeeded in being granted the Bhojpur estate in 1648. He then moved his capital away from Bhojpur Kadim in favor of Mithila, 20 km southwest of Dumraon in the present Buxar district. He built numerous buildings at Mithila, and the ruins of the old fort can still be seen at Bhojpur Kadim.[3]

During the ensuing succession war at the end of Shah Jahan's life, both Shah Shuja and Dara Shikoh sought Amar Singh's support, but since it was Shah Shuja who had helped Amar Singh obtain the Bhojpur raj, his decision was "a foregone conclusion".[3] During the wars that followed, Amar Singh unwaveringly gave support to Shah Shuja, including at the Battle of Bahadurpur between the two brothers in February 1658. Shah Shuja expressed appreciation in several firmans to Amar Singh during the course of the year, and promised rewards and favours in return, but after his defeat by Aurangzeb at the Battle of Khajwa in 1659, he was chased out of India altogether and ended up dying in exile in Arakan. Amar Singh ended up switching allegiance to Aurangzeb, who continued to recognize his rank and titles, and he died in 1665 after a peaceful final few years.[3]

Amar Singh was succeeded by his oldest son, Rudra Singh, although he was not officially recognised by Aurangzeb as raja until 1682. In the meantime, Amar Singh's younger brother Prabal Singh had gone to Delhi and sought Aurangzeb's support in making him raja instead. According to local tradition, Aurangzeb offered to do so if Prabal Singh converted to Islam, which he did, but he was not given rule over Bhojpur. The reason is unclear, but possibly because Rudra Singh had already established himself as a capable and loyal young ruler. As compensation, the disgruntled Prabal Singh was granted a jagir in the pargana of Piro as well as the title of raja. He returned from Delhi in 1671 and died a year later.[3]

In 1681, Rudra Singh revolted. The coming of the rainy season delayed the Mughals' response, but in October they had marched on Mithila and burned it to the ground, confiscating Rudra Singh's estates and putting them under direct Mughal rule. Rudra Singh escaped to the forests and harassed the Mughals using guerilla tactics. Eventually, Safi Khan, the governor of Bihar and an old ally of Amar Singh's, approached Rudra Singh to negotiate a truce. Rudra Singh agreed to apologise for his rebellion and pay an indemnity of 130,000 rupees to the Mughal government, while in return he was granted a pardon and restoration of his father's rank and title. The rank and title were not finalised until April 1682. Around that time, Rudra Singh was also appointed faujdar of the sarkar of Shahabad, indicating that he had fully won back the confidence of the Mughal administration. He had been replaced by one Adiqat Khan by 1683, however. Rudra Singh was later given extensive jagirs with an annual revenue of over 200,000 rupees, along with the rights to collect revenues in the pargana of Kharid in Jaunpur. He moved his capital from the destroyed Mithila to Buxar, and died there in 1699 of poison. He was succeeded by his cousin Mandhata Singh, son of Prabal Singh, who moved the capital back to Mithila.[3]

1700s

[edit]In 1745, Raja Horil Singh moved his capital to Dumraon, thus founding the Dumraon Raj; his nephews Buddh Singh and Udwant Singh founded the estates at Buxar and Jagdishpur.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Geonames.org. Bhojpur Kadīm". Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ a b c "Census of India 2011: Bihar District Census Handbook - Buxar, Part A (Village and Town Directory)". Census 2011 India. pp. 19–20, 23–98, 318–365, 681–82, 730–746. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Ansari, Tahir Hussain (2019). Mughal Administration and the Zamindars of Bihar. Routledge. pp. 34–84. ISBN 9781000651522. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Hodivala, S.H. (2018). Garg, Sanjay (ed.). Studies in Indo-Muslim History by S.H. Hodivala Volume II. Routledge. ISBN 9780429757778. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ Roy Choudhury, Pranab Chandra (1957). Bihar District Gazetteers: Shahabad. Bihar: Secretariat Press. p. 798. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gopal, Surendra (14 August 2020). Mapping Bihar: From Medieval to Modern Times. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-03416-6.

- ^ a b c d O'Malley, L.S.S. (1924). Bihar and Orissa District Gazetteers Shahabad. New Delhi: Logos Press. pp. 167–69. Retrieved 14 August 2020.