University of California, Berkeley

| |

Former names | University of California (1868–1958) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Fiat lux (Latin) |

Motto in English | "Let there be light" |

| Type | Public land-grant research university |

| Established | March 23, 1868[1] |

Parent institution | University of California |

| Accreditation | WSCUC |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $7.4 billion (2023)[2] |

| Chancellor | Richard Lyons |

| Provost | Benjamin E. Hermalin[3] |

Total staff | 23,524 (2020)[4] |

| Students | 45,307 (fall 2022)[5] |

| Undergraduates | 32,479 (fall 2022)[5] |

| Postgraduates | 12,828 (fall 2022)[5] |

| Location | , United States 37°52′19″N 122°15′30″W / 37.87194°N 122.25833°W |

| Campus | Core central: 178-acre (72-hectare)[6][7] Large suburb: 8,164-acre (3,304-hectare)[8] |

| Newspaper | The Daily Californian |

| Colors | Berkeley Blue California Gold[9] |

| Nickname | Golden Bears |

Sporting affiliations | |

| Mascot | Oski the Bear |

| Website | berkeley |

| |

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California)[10][11] is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after the Anglo-Irish philosopher George Berkeley, it is the state's first land-grant university and is the founding campus of the University of California system.[12]

Berkeley has an enrollment of more than 45,000 students. The university is organized around fifteen schools of study on the same campus, including the College of Chemistry, the College of Engineering, and the Haas School of Business. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity".[13] The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory was originally founded as part of the university.[14]

Berkeley was a founding member of the Association of American Universities and was one of the original eight "Public Ivy" schools. In 2021, the federal funding for campus research and development exceeded $1 billion.[15] Thirty-two libraries also compose the Berkeley library system which is the sixth largest research library by number of volumes held in the United States.[16][17][18]

Berkeley students compete in thirty varsity athletic sports, and the university is one of eighteen full-member institutions in the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC). Berkeley's athletic teams, the California Golden Bears, have also won 107 national championships, 196 individual national titles, and 223 Olympic medals (including 121 gold).[19][20] Berkeley's alumni, faculty, and researchers include 55 Nobel laureates[21] and 19 Academy Award winners,[22] and the university is also a producer of Rhodes Scholars,[23] Marshall Scholars,[24] and Fulbright Scholars.[25]

History

Founding

Made possible by President Lincoln's signing of the Morrill Act in 1862, the University of California was founded in 1868 as the state's first land-grant university, inheriting the land and facilities of the private College of California and the federal-funding eligibility of a public agricultural, mining, and mechanical arts college.[26] The Organic Act states that the "University shall have for its design, to provide instruction and thorough and complete education in all departments of science, literature and art, industrial and professional pursuits, and general education, and also special courses of instruction in preparation for the professions."[27][28]

Ten faculty members and forty male students made up the fledgling university when it opened in Oakland in 1869.[29] Frederick Billings, a trustee of the College of California, suggested that a new campus site north of Oakland be named in honor of Anglo-Irish philosopher George Berkeley.[30] The university began admitting women the following year.[31] In 1870, Henry Durant, founder of the College of California, became its first president. With the completion of North and South Halls in 1873, the university relocated to its Berkeley location with 167 male and 22 female students.[32][33] The first female student to graduate was in 1874, admitted in the first class to include women in 1870.[34]

Beginning in 1891, Phoebe Apperson Hearst funded several programs and new buildings and, in 1898, sponsored an international competition in Antwerp, where French architect Émile Bénard submitted the winning design for a campus master plan. Although the University of California system does not have an official flagship campus, many scholars and experts consider Berkeley to be its unofficial flagship. It shares this unofficial status with the University of California, Los Angeles.[35][36]

20th century

In 1905, the University Farm was established near Sacramento, ultimately becoming the University of California, Davis.[37] In 1919, the Los Angeles branch of the California State Normal School became the southern branch of the university, which ultimately became the University of California, Los Angeles.[38] By the 1920s, the number of campus buildings in Berkeley had grown substantially and included twenty structures designed by architect John Galen Howard.[39] In 1917, one of the nation's first ROTC programs was established at Berkeley[40] and its School of Military Aeronautics began training pilots, including Jimmy Doolittle. In 1926, future Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz established the first Naval ROTC unit at Berkeley.[41] Berkeley ROTC alumni include former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Army Chief of Staff Frederick C. Weyand, sixteen other general officers, ten Navy flag officers, and AFROTC alumna Captain Theresa Claiborne.[42]

In the 1930s, Ernest Orlando Lawrence helped establish the Radiation Laboratory (now Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) and invented the cyclotron, which won him the Nobel physics prize in 1939.[43] Using the cyclotron, Berkeley professors and Berkeley Lab researchers went on to discover sixteen chemical elements—more than any other university in the world.[44][45] In particular, during World War II and following Glenn Seaborg's then-secret discovery of plutonium, Lawrence's Radiation Laboratory began to contract with the U.S. Army to develop the atomic bomb. Physics professor J. Robert Oppenheimer was named scientific head of the Manhattan Project in 1942.[46][47] Along with the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley founded and was then a partner in managing two other labs, Los Alamos National Laboratory (1943) and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (1952).

In 1952, the University of California reorganized itself into a system of semi-autonomous campuses, with each campus given a chancellor, and Clark Kerr became Berkeley's first Chancellor, while Robert Sproul remained in place as the President of the University of California.[48] Berkeley gained a worldwide reputation for political activism in the 1960s. In 1964, the Free Speech Movement organized student resistance to the university's restrictions on political activities on campus—most conspicuously, student activities related to the Civil Rights Movement.[49][50]

The arrest in Sproul Plaza of Jack Weinberg, a recent Berkeley alumnus and chair of Campus CORE, prompted a series of student-led acts of formal remonstrance and civil disobedience that ultimately gave rise to the Free Speech Movement, which movement would prevail and serve as a precedent for student opposition to America's involvement in the Vietnam War.[51][52][53] In 1982, the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute (MSRI) was established on campus with support from the National Science Foundation and at the request of three Berkeley mathematicians—Shiing-Shen Chern, Calvin Moore, and Isadore M. Singer. The institute is now widely regarded as a leading center for collaborative mathematical research, drawing thousands of visiting researchers from around the world each year.[54][55][56]

21st century

In the current century, Berkeley has become less politically active, although more liberal.[57][58] Democrats outnumber Republicans on the faculty by a ratio of nine to one, which is a ratio similar to that of American academia generally.[59] The school has become more focused on STEM disciplines and fundraising.[60][61][62] In 2007, the Energy Biosciences Institute was established with funding from BP and Stanley Hall, a research facility and headquarters for the California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences, opened. Supported by a grant from alumnus James Simons, the Simons Institute for the Theory of Computing was established in 2012. In 2015, Berkeley and its sister campus, UCSF, established the Innovative Genomics Institute to develop CRISPR gene editing, and, in 2020, an anonymous donor pledged $252 million to help fund a new center for computing and data science. For the 2020 fiscal year, Berkeley set a fundraising record, receiving over $1 billion in gifts and pledges, and two years later, it broke that record, raising over $1.2 billion.[63][60][64][65]

Controversies

- Various research ethics, human rights, and animal rights advocates have been in conflict with Berkeley. Native Americans contended with the school over repatriation of remains from the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology.[66] Student activists have urged the university to cut financial ties with Tyson Foods and PepsiCo.[67][68][69] Faculty member Ignacio Chapela prominently criticized the university's financial ties to Novartis.[70] PETA has challenged the university's use of animals for research and argued that it may violate the Animal Welfare Act.[71][72]

- Cal's Memorial Stadium reopened in September 2012 after renovations. The university incurred a controversial $445 million of debt for the stadium and a new $153 million student athletic center, which it financed with the sale of special stadium endowment seats.[73] The roughly $18 million interest-only annual payments on the debt consumes 20 percent of Cal's athletics' budget; principal repayment begins in 2032 and is scheduled to conclude in 2113.[74]

- On May 1, 2014, Berkeley was named one of fifty-five higher education institutions under investigation by the U.S. Department of Education's Office of Civil Rights "for possible violations of federal law over the handling of sexual violence and harassment complaints" by the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault.[75] Investigations continued into 2016, with hundreds of pages of records released in April 2016, showing a pattern of documented sexual harassment and firings of non-tenured staff.[76]

- On July 25, 2019, Berkeley was removed from the U.S. News Best Colleges Ranking for misreporting statistics. Berkeley had originally reported that its two-year average alumni giving rate for fiscal years 2017 and 2016 was 11.6 percent, U.S. News said. The school later told U.S. News the correct average alumni giving rate for the 2016 fiscal year was just 7.9 percent. The school incorrectly overstated its alumni giving data to U.S. News since at least 2014. The alumni giving rate accounts for five percent of the Best Colleges ranking.[77]

- Berkeley community members have criticized UC Berkeley's increasing enrollment. Berkeley residents filed a lawsuit alleging that the university's expanding enrollment violated California Environmental Quality Act and that the area lacked the infrastructure to support more students.[78] Critics of the lawsuit accused these community members of NIMBYism.[79][80][81] In August 2021, a judge from the Superior Court of Alameda County ruled in favor of the residents, and on March 3, 2022, the California Supreme Court also ruled in favor of the residents, saying that the university needed to freeze its admission rates at 2020–2021 levels.[82] On March 11, 2022, state legislators released a proposal to change CEQA to exempt the university from its restrictions.[83] On March 14, Gavin Newsom signed the bill into law.[84] Berkeley has continued to face a housing shortage.[85]

Organization and administration

Name

Officially named the "University of California, Berkeley" it is often shortened to "Berkeley" in general reference or in an academic context (Berkeley Law, Berkeley Engineering, Berkeley Haas, Berkeley Public Health) and to "California" or "Cal" particularly when referring to its athletic teams (California Golden Bears).[86][87][88] In August 2022, a university task force was formed which recommended renaming the athletic identity to "Cal Berkeley" to further tie the athletic brand to academic prestige, and reduce public confusion.[89]

Governance

The University of California is governed by a twenty-six member Board of Regents, eighteen of whom are appointed by the Governor of California to 12-year terms. The board also has seven ex officio members, a student regent, and a non-voting student regent-designate.[90] Prior to 1952, Berkeley was the University of California, so the university president was also Berkeley's chief executive. In 1952, the university reorganized itself into a system of semi-autonomous campuses, with each campus having its own chief executive, a chancellor, who would, in turn, report to the president of the university system. Twelve vice-chancellors report directly to Berkeley's chancellor, and the deans of the fifteen colleges and schools report to the executive vice chancellor and provost, Berkeley's chief academic officer.[91] Twenty-three presidents and chancellors have led Berkeley since its founding.[92][48]

|

Presidents

|

Chancellors

|

Funding

With the exception of government contracts, public support is apportioned to Berkeley and the other campuses of the University of California system through the UC Office of the President and accounts for 12 percent of Berkeley's total revenues.[93] Berkeley has benefited from private philanthropy and alumni and their foundations have given to the university for operations and capital expenditures with the more prominent being J. Paul Getty, Ann Getty, Sanford Diller, Donald Fisher, Flora Lamson Hewlett, David Schwartz (Bio-Rad) and members of the Haas (Walter A. Haas, Rhoda Haas Goldman, Walter A. Haas Jr., Peter E. Haas, Bob Haas) family.[94]

Berkeley has also benefited from benefactors beyond its alumni ranks, notable among which are Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan; Vitalik Buterin, Patrick Collison, John Collison, the Ron Conway family, Daniel Gross, Dustin Moskovitz and Cari Tuna, along with Jane Street principals; BP; the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, billionaire Sir Li Ka-Shing, Israeli-Russian billionaire Yuri Milner, Thomas and Stacey Siebel, Sanford and Joan Weill, and professor Gordon Rausser ($50 million gift in 2020).[94] Hundreds of millions of dollars have been given anonymously.[95] The 2008–13 "Campaign for Berkeley" raised $3.13 billion from 281,855 donors, and the "Light the Way" campaign, which concluded at the end of 2023, has raised over $6.2 billion.[96]

Academics

Faculty and departments

Berkeley is a large, primarily residential research university with a majority of its enrolment in undergraduate programs but also offering a comprehensive doctoral program.[13] The university has been accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges Senior College and University Commission since 1949.[97] The university operates on a semester calendar and awarded 8,725 bachelor's, 3,286 master's or professional and 1,272 doctoral degrees in 2018–2019.[98]

There are 1,789 full-time and 886 part-time faculty members among the university's academic enterprise which is organized into fifteen colleges and schools that comprise 180 departments and 80 interdisciplinary units offering over 350 degree programs. Colleges serve both undergraduate and graduate students, while schools are generally graduate only, though some offer undergraduate majors or minors:

- College of Chemistry

- College of Computing, Data Science, and Society

- College of Engineering

- College of Environmental Design

- College of Letters and Science

- Goldman School of Public Policy

- Graduate School of Journalism

- Haas School of Business

- Rausser College of Natural Resources

- School of Information

- School of Education

- School of Law

- School of Public Health

- School of Social Welfare

- Wertheim School of Optometry

- UC Berkeley Extension

Undergraduate programs

The four-year, full-time undergraduate program offers 107 bachelor's degrees across the Haas School of Business (1), College of Chemistry (5), College of Engineering (20), College of Environmental Design (4), College of Letters and Science (67), Rausser College of Natural Resources (10), and individual majors (2).[99] The most popular majors are electrical engineering and computer sciences, political science, molecular and cell biology, environmental science, and economics.[100]

Requirements for undergraduate degrees include an entry-level writing requirement before enrollment (typically fulfilled by minimum scores on standardized admissions exams such as the SAT or ACT), completing coursework on "American History and Institutions" before or after enrollment by taking an introductory class, passing an "American Cultures Breadth" class at Berkeley, as well as requirements for reading and composition and specific requirements declared by the department and school.[101]

Graduate and professional programs

Berkeley has a "comprehensive" graduate program, with high coexistence with the programs offered to undergraduates, and offers interdisciplinary graduate programs with the medical schools at the University of California, San Francisco and Stanford University. The university offers Master of Arts, Master of Science, Master of Fine Arts, and PhD degrees in addition to professional degrees such as the Juris Doctor, Master of Business Administration, Master of Public Health, and Master of Design.[13][102] The university awarded 963 doctoral degrees and 3,531 master's degrees in 2017.[103] Admission to graduate programs is decentralized; applicants apply directly to the department or degree program. Most graduate students are supported by fellowships, teaching assistantships, or research assistantships.[103]

Library system

Doe Library serves as the Berkeley library system's reference, periodical, and administrative center, while most of the main collections reside in the subterranean Gardner Main Stacks and Moffitt Undergraduate Library. The Bancroft Library, which has over 400,000 printed volumes and 70 million manuscripts, pictures, and maps, maintains special collections that document the history of the western part of North America, with an emphasis on California, Mexico and Central America. The Bancroft Library also houses the Mark Twain Papers,[104] the Oral History Center,[105] the Center for the Tebtunis Papyri,[106] and the University Archives.[107]

Reputation and rankings

National

| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[108] | 5 |

| U.S. News & World Report[109] | 17 |

| Washington Monthly[110] | 13 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[111] | 8 |

| Global | |

| QS[112] | 12 |

| THE[113] | 9 |

| U.S. News & World Report[114] | 5 |

| National Program Rankings[115] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Program | Ranking | ||

| Biological Sciences | 3 (tie) | ||

| Biostatistics | 7 (tie) | ||

| Business | 7 (tie) | ||

| Chemistry | 1 (tie) | ||

| Clinical Psychology | 3 (tie) | ||

| Computer Science | 1 (tie) | ||

| Earth Sciences | 3 | ||

| Economics | 4 (tie) | ||

| Education | 14 (tie) | ||

| Engineering | 3 | ||

| English | 1 (tie) | ||

| Fine Arts | 15 (tie) | ||

| History | 1 | ||

| Law | 12 | ||

| Mathematics | 3 (tie) | ||

| Physics | 3 (tie) | ||

| Political Science | 4 (tie) | ||

| Psychology | 1 (tie) | ||

| Public Affairs | 4 (tie) | ||

| Public Health | 10 | ||

| Social Work | 4 (tie) | ||

| Sociology | 1 | ||

| Statistics | 2 | ||

| Global Subject Rankings[116] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Program | Ranking | ||

| Agricultural Sciences | 123 (tie) | ||

| Artificial Intelligence | 33 | ||

| Arts & Humanities | 11 | ||

| Biology & Biochemistry | 5 | ||

| Biotechnology & Applied Microbiology | 22 | ||

| Cell Biology | 42 (tie) | ||

| Chemical Engineering | 155 | ||

| Chemistry | 11 | ||

| Civil Engineering | 33 | ||

| Clinical Medicine | 171 | ||

| Computer Science | 10 | ||

| Condensed Matter Physics | 52 | ||

| Ecology | 7 | ||

| Economics & Business | 5 | ||

| Education & Educational Research | 66 | ||

| Electrical & Electronic Engineering | 72 (tie) | ||

| Energy & Fuels | 64 | ||

| Engineering | 19 | ||

| Environmental Engineering | 116 (tie) | ||

| Environment/Ecology | 6 | ||

| Geosciences | 30 | ||

| Green & Sustainable Science & Technology | 147 (tie) | ||

| Immunology | 68 (tie) | ||

| Infectious Diseases | 98 | ||

| Materials Science | 22 | ||

| Mathematics | 8 | ||

| Mechanical Engineering | 115 (tie) | ||

| Meteorology & Atmospheric Sciences | 57 | ||

| Microbiology | 19 | ||

| Molecular Biology & Genetics | 26 | ||

| Nanoscience & Nanotechnology | 64 | ||

| Neuroscience & Behavior | 37 | ||

| Optics | 24 | ||

| Physical Chemistry | 65 (tie) | ||

| Physics | 3 | ||

| Plant & Animal Science | 11 | ||

| Psychiatry/Psychology | 27 | ||

| Public, Environmental & Occupational Health | 38 | ||

| Radiology, Nuclear Medicine & Medical Imaging | 109 (tie) | ||

| Social Sciences & Public Health | 26 | ||

| Space Science | 3 | ||

| Water Resources | 38 | ||

- In the 2024 Center for World University Rankings (CWUR) list, Berkeley was the top public university in the nation and ranked 10th overall based on quality of education, alumni employment, quality of faculty, publications, influence, and citations.[117]

- In the 2023 Forbes’ America's Top Colleges list, Berkeley was the highest ranking public school and 5th overall.[108]

- In the 2023–2024 U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges Ranking, Berkeley was tied for both the top public school and for 15th overall.[118]

- In the 2025 The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse rankings, Berkeley was the highest ranking public school and 8th overall.[111]

Global

- In 2017, the Nature Index ranked the university the 9th largest contributor to papers published in 82 leading journals.[119][120]

- For 2024, the Center for World University Rankings (CWUR) ranked the university 12th in the world based on quality of education, alumni employment, quality of faculty, and research performance.[117]

Past rankings

In his memoirs, Clark Kerr records Berkeley's rise in the rankings (according to the National Academies) during the 20th century. The school's first ranking in 1906 placed it among the top six schools ("Big Six") in the nation. In 1934, it ranked second, tied with Columbia and the University of Chicago, behind only Harvard; in 1957, it was ranked as the only school second to Harvard. In 1964, Berkeley was named the "best balanced distinguished university", meaning the school had not only the most top departments but also the highest percentage of top ranking departments in its school. The school in 1993 was the only remaining member of the original 1906 "Big Six", along with Harvard; in that year Berkeley ranked first.[121]

The American Council on Education, a private non-profit association, ranked Berkeley tenth in 1934. However, by 1942, private funding had helped Berkeley rise to second place, behind only Harvard, based on the number of distinguished departments.[48] In 1985, Yale University admissions officer Richard Moll published Public Ivies: A Guide to America's Best Public Undergraduate Colleges and Universities which named Berkeley a "Public Ivy".[122][123][124][125] Since its inaugural 1990 reputational survey, Times Higher Education has considered Berkeley to be one of the world's "six super brands" along with the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge, Harvard University, MIT, and Stanford University.[126][127][128][129][130]

The 2010 United States National Research Council Rankings identified Berkeley as having the highest number of top-ranked doctoral programs in the nation. Berkeley doctoral programs that received a #1 ranking included English, German, Political Science, Geography, Agricultural and Resource Economics, Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, Genetics, Genomics, Epidemiology, Plant Biology, Computer Science, Electrical Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, and Civil and Environmental Engineering.[131]

Admissions and enrollment

| Race and ethnicity[132] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | 35% | ||

| White | 22% | ||

| Hispanic | 19% | ||

| Foreign national | 13% | ||

| Other[a] | 9% | ||

| Black | 2% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[b] | 22% | ||

| Affluent or middle class[c] | 78% | ||

For Fall 2022, Berkeley's total enrollment was 45,745: 32,831 undergraduate and 12,914 graduate students, with women accounting for 56% of undergraduates and 49% of graduate and professional students. It had 128,226 freshman applicants and accepted 14,614 (11.4%). Among enrolled freshman, the average unweighted GPA was 3.90.[133]

Berkeley's enrollment of National Merit Scholars was third in the nation until 2002, when participation in the National Merit program was discontinued.[134] For 2019, Berkeley ranked fourth in enrollment of recipients of the National Merit $2,500 Scholarship (132 scholars).[135][136] 27% of admitted students receive federal Pell grants.[137]

Berkeley students are eligible for a variety of public and private financial aid. Inquiries are processed through the Financial Aid and Scholarships Office, although schools such as the Haas School of Business[138] and Berkeley Law,[139] have their own financial aid offices.

| 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applicants | 128,226 | 109,597 | 88,076 | 87,398 | 89,621 | 85,057 | 82,571 | 78,923 | 73,794 | |||||

| Admits | 14,614 | 15,852 | 15,448 | 14,676 | 13,308 | 14,552 | 14,429 | 13,332 | 13,338 | |||||

| Admit rate | 11.4% | 14.5% | 17.5% | 16.8% | 14.8% | 17.1% | 17.5% | 16.9% | 18.1% | |||||

| Enrolled | 6,726 | 6,809 | 6,052 | 6,454 | 6,012 | 6,379 | 6,253 | 5,832 | 5,813 | |||||

| SAT (mid-50%) | N/A* | N/A* | 1300–1520 | 1330–1520 | 1300–1530 | 1300–1540 | 1930–2290 | 1870–2250 | 1840–2230 | |||||

| ACT (average) | N/A* | N/A* | 31 | 31 | 31 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 31 | |||||

| GPA (unweighted) | 3.90 | 3.87 | 3.86 | 3.89 | 3.89 | 3.91 | 3.86 | 3.87 | 3.85 | |||||

| * Berkeley began test-blind admissions in 2021. | ||||||||||||||

Discoveries and innovation

Natural sciences

- Atomic bomb – Physics professor J. Robert Oppenheimer was wartime director of Los Alamos National Laboratory and the Manhattan Project.

- Carbon 14 and photosynthesis – Martin Kamen and Sam Ruben first discovered carbon 14 in 1940, and Nobel laureate Melvin Calvin and his colleagues used carbon 14 as a molecular tracer to reveal the carbon assimilation path in photosynthesis, known as Calvin cycle.[140]

- Carcinogens – Identified chemicals that damage DNA. The Ames test was described in a series of papers in 1973 by Bruce Ames and his group at the university.

- Chemical elements – Sixteen elements have been discovered at Berkeley (technetium, astatine, neptunium, plutonium, americium, curium, berkelium, californium, einsteinium, fermium, mendelevium, nobelium, lawrencium, rutherfordium, dubnium, and seaborgium).[141][142]

- Covalent bond – Gilbert N. Lewis in 1916 described the sharing of electron pairs between atoms, and invented the Lewis notation to describe the mechanisms.

- CRISPR gene editing – Nobel laureate Jennifer Doudna discovered a precise and inexpensive way for manipulating DNA in human cells.[143]

- Cyclotron – Ernest O. Lawrence created a particle accelerator in 1934, and was awarded the Nobel Physics Prize in 1939.[144]

- Dark energy – Saul Perlmutter and many others in the Supernova Cosmology Project discover the universe is expanding because of dark energy 1998.

- Flu vaccine – Wendell M. Stanley and colleagues discovered the vaccine in the 1940s.

- Hydrogen bomb – Edward Teller, the father of hydrogen bomb, was a professor at Berkeley and a researcher at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

- Immunotherapy of cancer – James P. Allison discovers and develops monoclonal antibody therapy that uses the immune system to combat cancer 1992–1995.

- Molecular clock – Allan Wilson discovery in 1967.

- Neuroplasticity – Marian Diamond discovers structural, biochemical, and synaptic changes in brain caused by environmental enrichment 1964

- Oncogene – Peter Duesberg discovers first cancer causing gene in a virus 1970s.

- Telomerase – Elizabeth H. Blackburn, Carol Greider, and Jack Szostak discover enzyme that promotes cell division and growth 1985.

- Vitamin E – Gladys Anderson Emerson isolates Vitamin E in a pure form in 1952.[145]

Computer and applied sciences

- Berkeley RISC – David Patterson leads ARPA's VLSI project of microprocessor design 1980–1984.[146]

- Berkeley UNIX/Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) – The Computer Systems Research Group was a research group at Berkeley that was dedicated to enhancing AT&T Unix operating system and funded by Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Bill Joy modified the code and released it in 1977 under the open source BSD license, starting an open-source revolution.

- Deep sea diving – Joel Henry Hildebrand used helium with oxygen to mitigate decompression sickness.[147]

- GIMP – In 1995, Spencer Kimball and Peter Mattis began developing GIMP as a semester-long project at Berkeley.

- Polygraph – invented by John Augustus Larson and a police officer from the Berkeley Police Department in 1921.[148]

- Project Genie – DARPA funded project. It produced an early time-sharing system including the Berkeley Timesharing System, which was then commercialized as the SDS 940. Concepts from Project Genie influenced the development of the TENEX operating system for the PDP-10, and Unix, which inherited the concept of process forking from it.[149] Unix co-creator Ken Thompson worked on Project Genie while at Berkeley.

- SPICE – Donald O. Pederson develops the Simulation Program with Integrated Circuit Emphasis (SPICE) 1972.[150]

- Tcl programming language – developed by John Ousterhout in 1988.[151]

- Three-dimensional Transistor – Chenming Hu won the 2014 National Medal of Technology for developing the "first 3-dimensional transistors, which radically advanced semiconductor technology."[152]

- Vi text editor – Bill Joy created the first Vi editor in 1976.[153]

- Wetsuit – Hugh Bradner invents first wetsuit 1952.[154]

Companies and entrepreneurship

- Activision Blizzard, 1979 (as Activision), co-founder Alan Miller (BS) and Larry Kaplan (BA)

- AIG, 1919, founder Cornelius Vander Starr (Attended)

- Apple, 1976, co-founder Steve Wozniak (BS)[155]

- Berkeley Systems, 1987, co-founder Joan Blades (BA)[156]

- Bolt, Beranek and Newman, 1948, co-founder Richard Bolt (BA, MA, PhD)[157]

- Chernin Entertainment, 2009, founder Peter Chernin (BA)[158][159]

- Chez Panisse, 1971, founder Alice Waters (BA)[160]

- Coursera, 2012, co-founder Andrew Ng (PhD)

- Databricks, 2013, founders Ali Ghodsi (PhD), Matei Zaharia (PhD), Ion Stoica (Professor), Reynold Xin (PhD), Andy Konwinski (PhD), Arsalan Tavakoli-Shiraji (PhD), and Patrick Wendell (PhD)

- DHL, 1969, co-founder Larry Hillblom (JD)[161]

- eBay, 1995, founder Pierre Omidyar (Attended)[162][163]

- Gap Inc., 1969, co-founder Donald Fisher (BS)[164]

- Google Earth, 2001 (as KeyHole Inc.), co-founder John Hanke (MBA)[165]

- GrandCentral, 2009 (as Google Voice), co-founder Craig Walker (BA 1988, JD 1995)[166]

- HTC Corporation, 1997, co-founder Cher Wang (BA, MA)[167]

- Intel, 1968, co-founders Gordon Moore (BS) and Andy Grove (PhD)[168]

- LSI Logic, 1980, co-founder Robert Walker (BS)[169]

- Marvell Technology Group, 1995, co-founders Sehat Sutardja (MS, PhD) and Weili Dai (BA)[170]

- Morgan Stanley, 1924 (as Dean Witter & Co.), co-founder Dean G. Witter (BA)

- Mozilla Corporation, 2005, co-founder Mitchell Baker (BA, JD)

- Myspace, 2003, co-founder Tom Anderson (BA)[171]

- Opsware, 1997, co-founder Sik Rhee (BS)[172]

- PowerBar, 1986, co-founders Brian Maxwell (BA) and Jennifer Maxwell (BS)[173]

- RedOctane, 1999, co-founders Charles Huang (BA) and Kai Huang (BA)[174]

- Renaissance Technologies, 1982, founder James Simons (PhD)

- Rotten Tomatoes, 1998, founders Senh Duong (BA), Patrick Y. Lee (BA) and Stephen Wang (BA)

- SanDisk, 1988, co-founder Sanjay Mehrotra (BS, MS)[175]

- Scharffen Berger Chocolate Maker, 1996, co-founder John Scharffenberger (BA)[176]

- Softbank, 1981, founder Masayoshi Son (BA)

- Sun Microsystems, 1982, co-founder Bill Joy (MS)[177]

- Tesla, 2003, co-founder Marc Tarpenning (BS)

- The Learning Company, 1980, co-founder Warren Robinett (MS)[178]

- VMware, 1998, co-founders Diane Greene (MS) and Mendel Rosenblum (PhD)[179]

- Zilog, 1974, co-founder Ralph Ungermannn (BSEE)[180]

Campus

Much of the Berkeley campus is in the city limits of Berkeley with portion of the property extending into Oakland.[181] It encompasses approximately 1,232-acres, though the "central campus" occupies only the low-lying western 178-acres of this area. Of the remaining acres, approximately 200-acres are occupied by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; other facilities above the main campus include the Lawrence Hall of Science and several research units, notably the Space Sciences Laboratory, the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute, an 800-acre (320-hectare) ecological preserve, the University of California Botanical Garden and a recreation center in Strawberry Canyon. Portions of the mostly undeveloped, eastern area of the campus are actually within the City of Oakland; these portions extend from the Claremont Resort north through the Panoramic Hill neighborhood to Tilden Park.[182]

To the west of the central campus is the downtown business district of Berkeley; to the northwest is the neighborhood of North Berkeley, including the so-called Gourmet Ghetto, a commercial district known for high quality dining due to the presence of such world-renowned restaurants as Chez Panisse. Immediately to the north is a quiet residential neighborhood known as Northside with a large graduate student population;[183] situated north of that are the upscale residential neighborhoods of the Berkeley Hills. Immediately southeast of campus lies fraternity row and beyond that the Clark Kerr Campus and an upscale residential area named Claremont. The area south of the university includes student housing and Telegraph Avenue, one of Berkeley's main shopping districts with stores, street vendors and restaurants catering to college students and tourists. In addition, the university also owns land to the northwest of the main campus, a married student housing complex in the nearby town of Albany ("Albany Village" and the "Gill Tract"), and a field research station several miles to the north in Richmond, California.

The campus is home to several museums including the University of California Museum of Paleontology, the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, and the Lawrence Hall of Science. The Museum of Paleontology, found in the lobby of the Valley Life Sciences Building, showcases a variety of dinosaur fossils including a complete cast of a Tyrannosaurus Rex. The campus also offers resources for innovation and entrepreneurship, such as the Big Ideas Competition, the Sutardja Center for Entrepreneurship and Technology, and the Berkeley Haas Innovation Lab.[184] The campus is also home to the University of California Botanical Garden, with more than 12,000 individual species.

Architecture

What is considered the historic campus today was the result of the 1898 "International Competition for the Phoebe Hearst Architectural Plan for the University of California," funded by William Randolph Hearst's mother and initially held in the Belgian city of Antwerp; eleven finalists were judged again in San Francisco in 1899.[185] The winner was Frenchman Émile Bénard, who refused to personally supervise the implementation of his plan and the task was subsequently given to architecture professor John Galen Howard. Howard designed over twenty buildings, which set the tone for the campus up until its expansion in the 1950s and 1960s.

The structures forming the "classical core" of the campus were built in the Beaux-Arts Classical style, and include Hearst Greek Theatre, Hearst Memorial Mining Building, Doe Memorial Library, California Hall, Wheeler Hall, Le Conte Hall, Gilman Hall, Haviland Hall, Wellman Hall, Sather Gate, and the Sather Tower (nicknamed "the Campanile" after its architectural inspiration, St Mark's Campanile in Venice), the tallest university clock tower in the United States.[186] Buildings he regarded as temporary and non-academic were designed in shingle or Collegiate Gothic styles; examples of these are North Gate Hall, Dwinelle Annex, and Stephens Hall. Many of Howard's designs are recognized California Historical Landmarks[187] and are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Built in 1873 in a Victorian Second-Empire-style, South Hall, designed by David Farquharson, is the oldest university building in California. It, and the Frederick Law Olmsted-designed Piedmont Avenue east of the main campus, are two of the only surviving examples of the nineteenth-century campus. Other notable architects and firms whose work can be found in the campus and surrounding area are Bernard Maybeck[188] (Faculty Club); Julia Morgan (Hearst Women's Gymnasium and Julia Morgan Hall); William Wurster (Stern Hall); Moore Ruble Yudell (Haas School of Business); Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects (C.V. Starr East Asian Library), and Diller Scofidio + Renfro (Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive).

Natural features

Flowing into the main campus are two branches of Strawberry Creek. The south fork enters a culvert upstream of the recreational complex at the mouth of Strawberry Canyon and passes beneath California Memorial Stadium before appearing again in Faculty Glade. It then runs through the center of the campus before disappearing underground at the west end of campus. The north fork appears just east of University House and runs through the glade north of the Valley Life Sciences Building, the original site of the Campus Arboretum.

Trees in the area date from the founding of the university. The campus features numerous wooded areas, including: Founders' Rock, Faculty Glade, Grinnell Natural Area, and the Eucalyptus Grove, which is both the tallest stand of such trees in the world and the tallest stand of hardwood trees in North America.[189] The campus sits on the Hayward Fault, which runs directly through California Memorial Stadium.[190]

Student life and traditions

The official university mascot is Oski the Bear, who debuted in 1941. Previously, live bear cubs were used as mascots at Memorial Stadium until it was decided in 1940 that a costumed mascot would be a better alternative. Named after the Oski-wow-wow yell, he is cared for by the Oski Committee, whose members have exclusive knowledge of the identity of the costume-wearer.[191] The University of California Marching Band, which has served the university since 1891, performs at every home football game and at select road games as well. A smaller subset of the Cal Band, the Straw Hat Band, performs at basketball games, volleyball games, and other campus and community events.[192]

The UC Rally Committee, formed in 1901, is the official guardian of California's Spirit and Traditions. Wearing their traditional blue and gold rugbies, Rally Committee members can be seen at all major sporting and spirit events. Committee members are charged with the maintenance of the six Cal flags, the large California banner overhanging the Memorial Stadium Student Section and Haas Pavilion, the California Victory Cannon, Card Stunts and The Big "C" among other duties. The Rally Committee is also responsible for safekeeping of the Stanford Axe when it is in Cal's possession.[193]

Overlooking the main Berkeley campus from the foothills in the east, The Big "C" is an important symbol of California school spirit. The Big "C" has its roots in an early 20th-century campus event called "Rush," which pitted the freshman and sophomore classes against each other in a race up Charter Hill that often developed into a wrestling match. It was eventually decided to discontinue Rush and, in 1905, the freshman and sophomore classes banded together in a show of unity to build "the Big C."[194]

Students invented the college football tradition of card stunts. Then known as Bleacher Stunts, they were first performed during the 1910 Big Game and consisted of two stunts: a picture of the Stanford Axe and a large blue "C" on a white background. The tradition is continued today by the Rally Committee in the Cal student section and incorporates complicated motions, for example tracing the Cal script logo on a blue background with an imaginary yellow pen.[195]

The California Victory Cannon, placed on Tightwad Hill overlooking the stadium, is fired before every football home game, after every score, and after every Cal victory. First used in the 1963 Big Game, it was originally placed on the sidelines before moving to Tightwad Hill in 1971. The only time the cannon ran out of ammunition was during a game against Pacific in 1991, when Cal scored 12 touchdowns.[196] The Cal Mic Men, a standard at home football games, has recently expanded to involve basketball and volleyball. The traditional role comes from students holding megaphones and yelling, but now includes microphones, a dedicated platform during games, and the direction of the entire student section.[197]

Student housing

Berkeley students are offered a variety of housing options, including university-owned or affiliated residences, private residences, fraternities and sororities, and cooperative housing (co-ops). Berkeley students, and those of other local schools, have the option of living in one of the twenty cooperative houses participating in the Berkeley Student Cooperative (BSC), a nonprofit housing cooperative network consisting of 20 residences and 1250 member-owners.[198]

Fraternities and sororities

About three percent of undergraduate men and nine percent of undergraduate women—or 3,400 of total undergraduates—are active in Berkeley's Greek system.[199] University-sanctioned fraternities and sororities comprise over 60 houses affiliated with four Greek councils.[200][201]

Student-run organizations

Associated Students of the University of California (ASUC)

The Associated Students of the University of California (ASUC) is the official student association that controls funding for student groups and organizes on-campus student events. The two main political parties are "Student Action"[202] and "CalSERVE."[203] The organization was founded in 1887 and has an annual operating budget of $1.7 million (excluding the budget of the Graduate Assembly of the ASUC), in addition to various investment assets. Its alumni include multiple State Senators, Assemblymembers, and White House Administration officials.[204]

Media and publications

Berkeley's student-run online television station, CalTV, was formed in 2005 and broadcasts online. It is run by students with a variety of backgrounds and majors. Since the mid-2010s, it has been a program of the ASUC.[205] Berkeley's independent student-run newspaper is The Daily Californian. Founded in 1871, The Daily Cal became independent in 1971 after the campus administration fired three senior editors for encouraging readers to take back People's Park. The Daily Californian has both a print and online edition. Berkeley's FM student radio station, KALX, broadcasts on 90.7 MHz. It is run largely by volunteers, including both students and community members. Berkeley also features an assortment of student-run publications:

- California Law Review, law journal published by Berkeley Law, est. 1912.

- Berkeley Poetry Review, national poetry journal, est. 1974.

- Berkeley Fiction Review, American literary magazine, est. 1981.

- Heuristic Squelch, satirical newspaper, est. 1991.

- California Patriot, conservative political magazine, est. 2000.

- Berkeley Political Review, nonpartisan political magazine, est. 2001.

- Caliber Magazine, an "everything magazine," featuring articles and blogs on a wide range of topics, est. 2008.

- B-Side, music magazine, est. 2013.

- Smart Ass, liberal magazine, est. 2015.

- Berkeley Economic Review, economics journal, est. 2016.

- Business Berkeley, Haas undergraduate journal.

Student groups

There are ninety-four political student groups on campus, including MEChXA de UC Berkeley, Berkeley ACLU, Berkeley Students for Life, Campus Greens, The Sustainability Team (STEAM), the Berkeley Student Food Collective, Students for Sensible Drug Policy, Cal Berkeley Democrats, and the Berkeley College Republicans.[206] The Residence Hall Assembly (RHA) is the student-led umbrella organization that oversees event planning, legislation, sponsorships and other activities for over 7,200 on-campus undergraduate residents.[207]

Berkeley students also run a number of consulting groups, including the Berkeley Group, founded in 2003 and affiliated with the Haas School.[208] Students from various concentrations are recruited and trained to work on pro-bono consulting engagements with actual nonprofit clients. Berkeley Consulting, founded in 1996, has served over 140 companies across the high-tech, retail, banking, and non-profit sectors.[209]

ImagiCal has been the college chapter of the American Advertising Federation at Berkeley since the late 1980s.[210] The team competes annually in the National Student Advertising Competition, with students from disparate majors working together on a marketing case underwritten by a corporate sponsor. The Berkeley Forum is a nonpartisan student organization that hosts panels, debates, and speeches across a variety of fields.[211] Past speakers include Senator Rand Paul, entrepreneur and venture capitalist Peter Thiel, and Khan Academy founder Salman Khan.

Democratic Education at Cal, or DeCal, is a program that promotes the creation of professor-sponsored, student-facilitated classes.[212] DeCal arose out of the 1960s Free Speech movement and was officially established in 1981. The program offers around 150 courses on a vast range of subjects that appeal to the student community, including classes on the Rubik's Cube, blockchain, web design, metamodernism, cooking, Jewish art, 3D animation, and bioprinting.[213]

The campus is home to several a cappella groups, including Drawn to Scale, Artists in Resonance, Berkeley Dil Se, the UC Men's Octet, the California Golden Overtones, DeCadence, and Noteworthy. The University of California Men's Octet was founded in 1948. Since 1967, students and staff jazz musicians have had an opportunity to perform and study with the University of California Jazz Ensembles. For several decades it hosted the Pacific Coast Collegiate Jazz Festival, part of the American Collegiate Jazz Festival, a competitive forum for student musicians. PCCJF brought jazz artists including Hubert Laws, Sonny Rollins, Freddie Hubbard, and Ed Shaughnessy to the Berkeley campus as performers. Berkeley also hosts other performing arts groups in comedy, dance, acting and instrumental music.

Engineering Student Teams

Given Berkeley's STEM education, there are a variety of student-run engineering teams that focus on winning design and engineering competitions. Berkeley has two prominent amateur rocketry teams: Space Enterprise at Berkeley (SEB)[214] and Space Technologies and Rocketry (STAR).[215] Both have launched solid-fuel sounding rockets and are currently developing liquid propellant rockets. The university also has two Formula SAE teams: Berkeley Formula Racing[216] and Formula Electric Berkeley.[217] Both of these teams participate in Formula SAE–run competitions, with the former focusing on internal combustion engines and the latter on electric motors. Berkeley has a number of other vehicle teams, including CalSol,[218] CalSMV,[219] and Human Powered Vehicle.[220]

Athletics

The university's athletic teams are known as the California Golden Bears, often shortened to "Cal Bears" or just "Cal," and were historically members of the NCAA Division I Pac-12 Conference (Pac-12). Cal is also a member of the Mountain Pacific Sports Federation in several sports not sponsored by the Pac-12 and the America East Conference in women's field hockey. In 2024, Cal joined the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC).[221] The first school colors, established in 1873 by a committee of students, were Yale Blue and gold.[222][223] Yale Blue was originally chosen because many of the university's inaugural faculty were Yale graduates, including Henry Durant, its first president. Blue and gold were specified and made the official colors of the university and the state colors of California in 1955.[222][224] In 2014, the athletic department specified a darker blue.[225][226]

The California Golden Bears have won national championships in baseball (2), men's basketball (2), men's crew (15), women's crew (3), football (5), men's golf (1), men's gymnastics (4), men's lacrosse (1), men's rugby (26), softball (1), men's swimming & diving (4), women's swimming & diving (3), men's tennis (1), men's track & field (1), and men's water polo (13). Students and alumni have also won 207 Olympic medals.[227]

California finished in first place in the 2007–08 Fall U.S. Sports Academy Directors' Cup standings (now the NACDA Directors' Cup), a competition measuring the best overall collegiate athletic programs in the country, with points awarded for national finishes in NCAA sports.[228] It finished the 2007–08 competition in seventh place with 1119 points.[229] Most recently, California finished in third place in the 2010–11 NACDA Directors' Cup with 1219.50 points, finishing behind Stanford and Ohio State. This is California's highest ever finish in the Director's Cup.[230] The Golden Bears' traditional arch-rival is the Stanford Cardinal, and the most anticipated sporting event between the two universities is the annual football match dubbed the Big Game, celebrated with spirit events on both campuses. Since 1933, the winner of the Big Game has been awarded custody of the Stanford Axe. Other sporting games between these rivals have related names such as the Big Splash (water polo) or the Big Kick (soccer).[231]

Notable alumni, faculty, and staff

Faculty and staff

- Shiing-Shen Chern, a leading geometer of the 20th century, co-founded the renowned Mathematical Sciences Research Institute and served as its founding Director until 1984.[232][54]

- Physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer was scientific director of the Manhattan Project and was the founder of the Berkeley Center for Theoretical Physics.[233]

- Faculty member Edward Teller was (together with Stanislaw Ulam) the "father of the hydrogen bomb," who laid important foundations for the establishment of Space Sciences Laboratory at Berkeley.[234]

- Ernest Lawrence, a Nobel laureate in physics who invented the cyclotron at Berkeley, and founded the Radiation Laboratory on campus, which later became the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.[235]

- Gilbert N. Lewis, former Dean of the College of Chemistry, was nominated 41 times for Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[236][237] He mentored and influenced numerous Berkeley Nobel laureates, including Harold Urey (1934 Nobel Prize), William F. Giauque (1949 Nobel Prize), Glenn T. Seaborg (1951 Nobel Prize), Willard Libby (1960 Nobel Prize), and Melvin Calvin (1961 Nobel Prize).[238][239]

- Glenn T. Seaborg, a Nobel laureate in chemistry who discovered or co-discovered ten chemical elements at Berkeley and served as Chancellor from 1958 to 1961.[240][241]

- Hans Albert Einstein, the first son of Albert Einstein and a world's leading scholar in hydraulic engineering, was a long-time faculty member at Berkeley.[242]

- Steven Chu (PhD 1976), the 12th United States Secretary of Energy and Nobel laureate in physics, was Director of Berkeley Lab from 2004 to 2009.

- Janet Yellen, 78th United States Secretary of Treasury and the 15th Chair of the Federal Reserve, is a professor emeritus at Berkeley Haas School of Business and the Department of Economics.[243][244]

Alumni

Alumni have included 260 American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows,[245] 34 Pulitzer Prize winners, 25 living billionaire alumni,[246] 22 cabinet members, 68 recipients of the National Medal of Science, 190 recipients of the MacArthur Fellowship,[247] 144 members of the National Academy of Sciences,[248] 139 Guggenheim Fellows, and 125 Sloan Fellows, and 75 members of the National Academy of Engineering.[249][250]

-

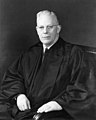

Earl Warren, BA 1912, LLB 1914, 14th Chief Justice of the United States, 30th Governor of California

-

Robert Reich, Professor of Public Policy, 22nd United States Secretary of Labor

-

Christina Romer, Professor of Economics, 25th Chairperson of the President's Council of Economic Advisers

-

Steve Wozniak, BS 1986, cofounder of Apple Inc.

-

Eric Schmidt, MS 1979, PhD 1982, Executive Chairman of Alphabet

-

Edmund Gerald "Jerry" Brown Jr., BA 1961, 34th & 39th Governor of California

-

Blake R. Van Leer, MS 1920, inventor, civil rights advocate, president of Georgia Tech

-

Gregory Peck, BA 1939, Academy Award–winning actor

-

Natalie Coughlin, BA 2005, multiple gold medal-winning Olympic swimmer

-

Pedro Nel Ospina Vázquez, BA 1878, President of Colombia 1922–1926

-

Robert McNamara, BA 1937, 5th President of World Bank, 8th United States Secretary of Defense, President of Ford Motor Company

-

Ed Meese, LL.B. 1958, 75th United States Attorney General

-

Daniel Kahneman, PhD 1961, awarded the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for his work in Prospect theory

Government

Berkeley alumni have served in a range of prominent government offices, both domestic and foreign, including Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court (Earl Warren, BA, JD); United States Attorney General (Edwin Meese III, JD); United States Secretary of State (Dean Rusk, LLB); United States Secretary of the Treasury (W. Michael Blumenthal, BA, and G. William Miller, JD); United States Secretary of Defense (Robert McNamara, BS); United States Secretary of the Interior (Franklin Knight Lane, 1887); United States Secretary of Transportation and United States Secretary of Commerce (Norman Mineta, BS); United States Secretary of Agriculture (Ann Veneman, MPP); National Security Advisor (Robert C. O'Brien, JD); scores of federal judges and members of the United States Congress (10 currently serving) and United States Foreign Service; governors of California (George C. Pardee; Hiram W. Johnson; Earl Warren, BA and LLB; Jerry Brown, BA; and Pete Wilson, JD), Michigan (Jennifer Granholm, BA), and the United States Virgin Islands (Walter A. Gordon, BA); Lieutenant General of the United States Army (Jimmy Doolittle, BA); Major General of the United States Marine Corps (Oliver Prince Smith); Brigadier General of the United States Marine Corps (Bertram A. Bone, BS); Director of the Central Intelligence Agency and Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission (John A. McCone, BS); chair and members of the Council of Economic Advisers (Michael Boskin, BA, PhD.; Sandra Black, BA; Jesse Rothstein, PhD; Robert Seamans, PhD; Jay Shambaugh, PhD; James Stock, MA, PhD); Governor of the Federal Reserve System (H. Robert Heller, PhD) and President and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (William C. Dudley, PhD); Commissioners of the SEC (Troy A. Paredes, BA) and the FCC (Rachelle Chong, BA); and United States Surgeon General (Kenneth P. Moritsugu, MPH).

Foreign alumni include the President of Colombia 1922–1926, (Pedro Nel Ospina Vázquez, BA); the President of Mexico (Francisco I. Madero, attended 1892–93); the President and Prime Minister of Pakistan; the Premier of the Republic of China (Sun Fo, BA); the President of Costa Rica (Miguel Angel Rodriguez, MA, PhD); and members of parliament of the United Kingdom (House of Lords, Lydia Dunn, Baroness Dunn, BS), India (Rajya Sabha, the upper house, Prithviraj Chavan, MS); Iran (Mohammad Javad Larijani, PhD); Nigerian Minister of Science and Technology and first Executive Governor of Abia State (Ogbonnaya Onu, PhD); Barbados' Ambassador to Brazil (Tonika Sealy-Thompson, PhD). Alumni have also served in many supranational posts, notable among which are President of the World Bank (Robert McNamara, BS); Deputy Prime Minister of Spain and managing director of the International Monetary Fund (Rodrigo Rato, MBA); executive director of UNICEF (Ann Veneman, MPP); member of the European Parliament (Bruno Megret, MS); and judge of the World Court (Joan Donoghue, JD).

Science

Nobel laureate William F. Giauque (BS 1920, PhD 1922) investigated chemical thermodynamics, Nobel laureate Willard Libby (BS 1931, PhD 1933) pioneered radiocarbon dating, Nobel laureate Willis Lamb (BS 1934, PhD 1938) examined the hydrogen spectrum, Nobel laureate Hamilton O. Smith (BA 1952) applied restriction enzymes to molecular genetics, Nobel laureate Robert Laughlin (BA 1972) explored the fractional quantum Hall effect, and Nobel laureate Andrew Fire (BA 1978) helped to discover RNA interference-gene silencing by double-stranded RNA. Nobel laureate Glenn T. Seaborg (PhD 1937) collaborated with Albert Ghiorso (BS 1913) to discover twelve chemical elements, such as americium, berkelium, and californium. David Bohm (PhD 1943) discovered Bohm diffusion. Nobel laureate Yuan T. Lee (PhD 1965) developed the crossed molecular beam technique for studying chemical reactions. Carol Greider (PhD 1987) was awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize in medicine for discovering a key mechanism in the genetic operations of cells. Harvey Itano (BS 1942) conducted breakthrough work on sickle cell anemia that marked the first time a disease was linked to a molecular origin.[253]

Narendra Karmarkar (PhD 1983) is known for the interior point method, a polynomial algorithm for linear programming known as Karmarkar's algorithm.[254] National Medal of Science laureate Chien-Shiung Wu (PhD 1940), often known as the "Chinese Madame Curie," disproved the Law of Conservation of Parity for which she was awarded the inaugural Wolf Prize in Physics.[255] Kary Mullis (PhD 1973) was awarded the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his role in developing the polymerase chain reaction,[256] a method for amplifying DNA sequences. Olga Hartman (MA 1933, PhD 1936) was a zoologist who described hundreds of species of polychaete worms.[257][258][259] Edward P. Tryon (PhD 1967) is the physicist who first said our universe originated from a quantum fluctuation of the vacuum.[260][261][262] John N. Bahcall (BS 1956) worked on the Standard Solar Model and the Hubble Space Telescope,[263] resulting in a National Medal of Science.[263] Peter Smith (BS 1969) was the principal investigator and project leader for the NASA robotic explorer Phoenix,[264] which physically confirmed the presence of water on the planet Mars for the first time.[265] Astronauts James van Hoften (BS 1966), Margaret Rhea Seddon (BA 1970), Leroy Chiao (BS 1983), and Rex Walheim (BS 1984) have orbited the Earth in NASA's fleet of Space Shuttles.

Computers

Berkeley alumni have developed a number of key technologies associated with the personal computer and the Internet.[266] Unix was created by alumnus Ken Thompson (BS 1965, MS 1966) along with colleague Dennis Ritchie. Alumni such as L. Peter Deutsch[267][268][269] (PhD 1973), Butler Lampson (PhD 1967), and Charles P. Thacker (BS 1967)[270] worked with Ken Thompson on Project Genie and then formed the ill-fated US Department of Defense-funded Berkeley Computer Corporation (BCC), which was scattered throughout the Berkeley campus in non-descript offices to avoid anti-war protestors.[271] After BCC failed, Deutsch, Lampson, and Thacker joined Xerox PARC, where they developed a number of pioneering computer technologies, culminating in the Xerox Alto that inspired the Apple Macintosh. In particular, the Alto used a computer mouse, which had been invented by Doug Engelbart (BEng 1952, PhD 1955). Thompson, Lampson, Engelbart, and Thacker[272] all later received a Turing Award. Also at Xerox PARC was Ronald Schmidt (BS 1966, MS 1968, PhD 1971), who became known as "the man who brought Ethernet to the masses."[273]

Another Xerox PARC researcher, Charles Simonyi (BS 1972), pioneered the first WYSIWIG word processor program and was recruited personally by Bill Gates to join the fledgling company known as Microsoft to create Microsoft Word. Simonyi later became the first repeat space tourist, blasting off on Russian Soyuz rockets to work at the International Space Station orbiting the Earth. In 1977, a graduate student in the computer science department named Bill Joy (MS 1982) assembled[274] the original Berkeley Software Distribution, commonly known as BSD Unix. Joy, who went on to co-found Sun Microsystems, also developed the original version of the terminal console editor vi, while Ken Arnold (BA 1985) created Curses, a terminal control library for Unix-like systems that enables the construction of text user interface (TUI) applications. Working alongside Joy at Berkeley were undergraduates William Jolitz (BS 1997) and his future wife Lynne Jolitz (BA 1989), who together created 386BSD, a version of BSD Unix that runs on Intel CPUs and evolved into the BSD family of free operating systems and the Darwin operating system underlying Apple Mac OS X.[275] Eric Allman (BS 1977, MS 1980) created SendMail, a Unix mail transfer agent that delivers about twelve percent of the email in the world.[276]

The XCF, an undergraduate research group located in Soda Hall, has been responsible for a number of notable software projects, including GTK+ (Peter Mattis, BS 1997), The GIMP (Spencer Kimball, BS 1996), and the initial diagnosis of the Morris worm.[277] In 1992, Pei-Yuan Wei (BS 1990)[278] an undergraduate at the XCF, created ViolaWWW, one of the first graphical web browsers. ViolaWWW was the first browser to have embedded scriptable objects, stylesheets, and tables. He donated the code to Sun Microsystems, inspiring Java applets. ViolaWWW also inspired researchers at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications to create the Mosaic web browser,[279] a pioneering web browser that became Microsoft Internet Explorer.

Billionaires

Billionaire alumni include Gordon Moore (Intel founder), James Harris Simons (Renaissance Technologies), Masayoshi Son (SoftBank),[280] Jon Stryker (Stryker Medical Equipment),[281] Eric Schmidt (former Google Chairman) and Wendy Schmidt, Michael Milken, Bassam Alghanim, Kutayba Alghanim,[282] Charles Simonyi (Microsoft), Cher Wang (HTC), Robert Haas (Levi Strauss & Co.), Carlos Rodriguez-Pastor (Interbank, Peru),[283] Fayez Sarofim, Daniel S. Loeb, Paul Merage, David Hindawi, Orion Hindawi, Bill Joy (Sun Microsystems founder), Victor Koo, Tony Xu (DoorDash), Lowell Milken, Nathaniel Simons and Laura Baxter-Simons, Liong Tek Kwee and Liong Seen Kwee,[284] Elizabeth Simons and Mark Heising,[285] Oleg Tinkov, and Alice Schwartz.

Pulitzer Prize winners

Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Marguerite Higgins (BA 1941) was a pioneering female war correspondent[286][287] who covered World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War.[288] Novelist Robert Penn Warren (MA 1927) won three Pulitzer Prizes,[289] including one for his novel All the King's Men, which was later made into an Academy Award-winning[290] movie. Pulitzer Prize–winning cartoonist Rube Goldberg (BS 1904) invented the comically complex—yet ultimately trivial—contraptions known as Rube Goldberg machines. Journalist Alexandra Berzon (MA 2006) won a Pulitzer Prize in 2009,[291] and journalist Matt Richtel (BA 1989), who also coauthors the comic strip Rudy Park under the pen name of "Theron Heir,"[292] won the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting.[293] Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Leon Litwack (BA[294] 1951, PhD 1958) taught as a professor at UC Berkeley for 43 years;[295] three other UC Berkeley professors have also received the Pulitzer Prize. Alumna and professor Susan Rasky (BA 1974) won the Polk Award for journalism in 1991. USC Professor and Berkeley alumnus Viet Thanh Nguyen's (PhD 1997) first novel The Sympathizer won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.[296]

Fiction and screenwriters

Irving Stone (BA 1923) wrote the novel Lust for Life, which was later made into an Academy Award-winning film of the same name starring Kirk Douglas as Vincent van Gogh. Stone also wrote The Agony and the Ecstasy, which was later made into a film of the same name starring Oscar winner Charlton Heston as Michelangelo. Mona Simpson (BA 1979) wrote the novel Anywhere But Here, which was later made into a film of the same name starring Oscar-winning actress Susan Sarandon. Terry McMillan (BA 1986) wrote How Stella Got Her Groove Back, which was later made into a film of the same name starring Oscar-nominated actress Angela Bassett. Randi Mayem Singer (BA 1979) wrote the screenplay for Mrs. Doubtfire, which starred Oscar-winning actor Robin Williams and Oscar-winning actress Sally Field. Audrey Wells (BA 1981) wrote the screenplay The Truth About Cats & Dogs, which starred Oscar-nominated actress Uma Thurman. James Schamus (BA 1982, MA 1987, PhD 2003) has collaborated on screenplays with Oscar-winning director Ang Lee on the Academy Award-winning movies Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Brokeback Mountain.

Academy and Emmy Award winners

Berkeley alumni have won 20 Academy Awards and 25 Emmy Awards. Gregory Peck (BA 1939), nominated for four Oscars during his career, won an Oscar for acting in To Kill a Mockingbird. Chris Innis (BA 1991) won the 2010 Oscar for film editing for her work on best picture winner, The Hurt Locker. Walter Plunkett (BA 1923) won an Oscar for costume design (for An American in Paris). Freida Lee Mock (BA 1961) and Charles H. Ferguson (BA 1978) have each[297][298] won an Oscar for documentary filmmaking. Mark Berger (BA 1964) has won four Oscars for sound mixing and is an adjunct professor at UC Berkeley.[299] Edith Head (BA 1918), who was nominated for 34 Oscars during her career, won eight Oscars for costume design. Joe Letteri (BA 1981[300]) has won four Oscars for Best Visual Effects in the James Cameron film Avatar and the Peter Jackson films King Kong, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King.[301] Emmy Award winners include Jon Else (BA 1968) for cinematography; Andrew Schneider (BA 1973) for screenwriting; Linda Schacht (BA 1966, MA 1981), two for broadcast journalism;[302][303] Christine Chen (dual-BA's 1990), two for broadcast journalism;[304] Kathy Baker (BA 1977), three for acting; Ken Milnes (BS 1977), four for broadcasting technology; and Leroy Sievers (BA 1977),[305] twelve for production. Elisabeth Leamy (BA 1989) is the recipient of thirteen Emmy awards.[306][307][308]

Music and entertainment

Former undergraduates have participated in the contemporary music industry, such as Grateful Dead bass guitarist Phil Lesh, the Police drummer Stewart Copeland,[309] Rolling Stone Magazine founder Jann Wenner, the Bangles lead singer Susanna Hoffs (BA 1980), Counting Crows lead singer Adam Duritz, electronic music producer Giraffage, MTV correspondent Suchin Pak (BA 1997),[310] AFI musicians Davey Havok and Jade Puget (BA 1996), and solo artist Marié Digby ("Say It Again"). People Magazine included Third Eye Blind lead singer and songwriter Stephan Jenkins (BA 1987) in the magazine's list of 50 Most Beautiful People.[311] Alumni have also acted in classic television series such as Karen Grassle (BA 1965) who played Caroline Ingalls in Little House on the Prairie, Jerry Mathers (BA 1974) who starred in Leave it to Beaver, and Roxann Dawson (BA 1980) who portrayed B'Elanna Torres on Star Trek: Voyager.

Sports

Sport alumni include tennis athlete Helen Wills Moody (BA 1925) won 31 Grand Slam titles, including eight singles titles at Wimbledon. Tarik Glenn (BA 1999) is a Super Bowl XLI champion. Michele Tafoya (BA 1988) is a sports television reporter for ABC Sports and ESPN.[312] Sports agent Leigh Steinberg (BA 1970, JD 1973) has represented professional athletes such as Steve Young, Troy Aikman, and Oscar De La Hoya; Steinberg has been called the real-life inspiration[313] for the title character in the Oscar-winning[314] film Jerry Maguire (portrayed by Tom Cruise). Matt Biondi (BA 1988) won eight Olympic gold medals during his swimming career, in which he participated in three different Olympics. At the Beijing Olympics in 2008, Natalie Coughlin (BA 2005) became the first American female athlete in modern Olympic history to win six medals in one Olympics.[315]

See also

- Blockeley

- Higher Education Recruitment Consortium

- Tsinghua-Berkeley Shenzhen Institute

- World Community Grid

Notes

- ^ Consists of Multiracial Americans and those who prefer to not say.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

References

- ^ "A brief history of the University of California". Academic Personnel and Programs. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ As of June 30, 2023; Total Endowment Assets. "Annual Endowment Report, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2023" (PDF). University of California.

- ^ "Home | Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost". evcp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ "About Berkeley: What We Do". Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c "UC Berkeley Quick Facts". UC Berkeley Office of Planning and Analysis. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ "College Navigator – University of California-Berkeley". National Center for Education Statistics.

- ^ "UC Berkeley Zero Waste Plan" (PDF). University of California-Berkeley. September 2019. p. 5. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "University of California 21/22 Annual Financial Report" (PDF). University of California. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 23, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ "Primary Palettes". Berkeley Brand Guidelines. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ^ "Trademark Use Guidelines and Requirements" (PDF). University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ^ "Our Name". The Berkeley Brand Manual (PDF). Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley: Office of Communications and Public Affairs. June 2019. p. 34. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- ^ "History & discoveries". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Carnegie Classifications: University of California-Berkeley". Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ^ "Berkeley Lab: What's in a Name?". www.lbl.gov. Retrieved July 24, 2024.

- ^ "Table 20. Campus funding for sponsored research tops $1 billion for first time". Berkeley News. August 16, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "Berkeley Library Facts" (PDF). www.lib.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 1, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "New addition to UC Berkeley Main Library dedicated to former UC President David Gardner". Berkeley.edu. June 12, 1997. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- ^ "The Nation's Largest Libraries". American Library Association. July 7, 2006. Archived from the original on November 25, 2022.

- ^ "California Golden Bears Olympic Medals". University of California Golden Bears Athletics. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ "Cal National Champions". University of California Golden Bears Athletics. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ "Berkeley's Nobel laureates". UC Berkeley Inspire. Retrieved September 20, 2024.

- ^ "Berkeley Law Distinguished Alumni". sfgate.com. February 26, 2012.

- ^ "US Rhodes Scholars Over Time". www.rhodeshouse.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ "Statistics". www.marshallscholarship.org. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- ^ "Top Producers". us.fulbrightonline.org. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ Stadtman, Verne A. (1970). The University of California, 1868–1968. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 34.

- ^ "History of UC Berkeley". University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010.

Founded in the wake of the gold rush by leaders of the newly established 31st state, the University of California's flagship campus at Berkeley has become one of the preeminent universities in the world.

- ^ Berdahl, Robert (October 8, 1998). "The Future of Flagship Universities". University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011.

The issue I want to talk about tonight is the future of "flagship" universities, institutions like the University of Texas at Austin, or Texas A&M at College Station, or the University of California, Berkeley. This is not an easy topic to talk about for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the fact that those of us in "systems" of higher education are frequently actively discouraged from using the term "flagship" to refer to our campuses because it is seen as hurtful to the self-esteem of colleagues at other institutions in our systems.

- ^ "A brief history of the University of California". University of California Office of the President. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ Wollenberg, Charles (2002). "Chapter 2: Tale of Two Towns". Berkeley, A City in History. Berkeley Public Library. Archived from the original on June 12, 2009. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ "A History of Women at Cal | Campus Climate, Community Engagement & Transformation". Campus Climate at Berkeley. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- ^ "The Centennial of The University of California, 1868–1968". Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- ^ "University of California History Digital Archives". Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ^ Smith, Mackenzie (2018). "Celebrating Women at Rausser College, Past & Present". College of Natural Resources, University of California Berkeley. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^

- "The top 50 US colleges that pay off the most in 2020". CNBC. July 28, 2020.

- Medina, Jennifer (July 19, 2018). "You've Heard of Berkeley. Is Merced the Future of the University of California?". The New York Times. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

The disparity between the state's population and its university enrollment is most stark at the state's flagship campuses: at University of California, Los Angeles, Latinos make up about 21 percent of all students; at Berkeley, they account for less than 13 percent.

- "Gov. Brown says 'normal' Californians can't get into Berkeley, a problem some Californians blame on Brown". www.insidehighered.com. January 23, 2015. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- "Engines of Inequality: Diminishing Equity in the Nation's Premier Public Universities" (PDF). 2006. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ See, for example:

- Hess, Abigail Johnson (July 28, 2020). "The top 50 U.S. colleges that pay off the most in 2020". CNBC.

University of California, Berkeley, is the flagship school of the University of California system. Located in Berkeley, California, near San Francisco, the university enrolls some 31,348 undergraduate students.

- Medina, Jennifer (July 19, 2018). "You've Heard of Berkeley. Is Merced the Future of the University of California?". The New York Times.

The disparity between the state's population and its university enrollment is most stark at the state's flagship campuses: at University of California, Los Angeles, Latinos make up about 21 percent of all students; at Berkeley, they account for less than 13 percent.

- Rivard, Ry (January 22, 2015). "The New Normal at Berkeley". Inside Higher Ed.

California Governor Jerry Brown this week said the state's flagship – the University of California at Berkeley – has closed its doors to "normal" people.

- Gerald, Danette; Haycock, Kati (2006). "Engines of Inequality: Diminishing Equity in the Nation's Premier Public Universities". Education Trust – via ERIC.

Flagship Report Card: Grades ... U. OF CALIFORNIA-BERKELEY CA 44.0% 13.9% 0.32 F 35.1% 23.9% 0.68 -53.6%

- Hess, Abigail Johnson (July 28, 2020). "The top 50 U.S. colleges that pay off the most in 2020". CNBC.

- ^ "About UC Berkeley – History". UC Berkeley. Archived from the original on September 5, 2008. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ^ Douglass, John; Thomas, Sally. "University of California History Digital Archives: Los Angeles General History". www.lib.berkeley.edu. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ "John Galen Howard and the design of the City of Learning, the UC Berkeley campus". UC Berkeley. Retrieved December 24, 2010.

- ^ "History of Army ROTC". UC Berkeley Army ROTC. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Naval Activities World War II by State". Patrick Clancey. Retrieved March 19, 2012.