Battle of the Barents Sea

| Battle of the Barents Sea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |||||||

Battle of the Barents Sea, Erwin J. Kappes (sinking of the Friedrich Eckholdt) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2 light cruisers 6 destroyers 2 corvettes 1 minesweeper 2 trawlers |

2 heavy cruisers 6 destroyers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

250 killed 1 destroyer sunk 1 minesweeper sunk 1 destroyer damaged |

330 killed 1 destroyer sunk 1 heavy cruiser damaged | ||||||

The Battle of the Barents Sea was a World War II naval engagement on 31 December 1942 between warships of the German Navy (Kriegsmarine) and British ships escorting Convoy JW 51B to Kola Inlet in the USSR. The action took place in the Barents Sea north of North Cape, Norway. The German raiders' failure to inflict significant losses on the convoy infuriated Hitler, who ordered that German naval strategy would henceforth concentrate on the U-boat fleet rather than surface ships.

Background

[edit]JW 51B

[edit]Convoy JW 51B comprised fourteen merchant ships carrying war materials to the USSR, about 202 tanks, 2,046 vehicles, 87 fighters, 33 bombers, 11,500 short tons (10,400 t) of fuel, 12,650 short tons (11,480 t) of aviation fuel and just over 54,000 short tons (49,000 t) of other supplies. They were protected by the destroyers HMS Achates, Orwell, Oribi, Onslow, Obedient and Obdurate, the Flower-class corvettes HMS Rhododendron and Hyderabad, the minesweeper HMS Bramble and trawlers Vizalma and Northern Gem. The escort commander was Captain Robert Sherbrooke (flag in Onslow). The convoy sailed in the dead of winter to preclude attacks by German aircraft like those that had devastated Convoy PQ 17.[1] Force R (Rear-Admiral Robert L. Burnett), with the cruisers HMS Sheffield and Jamaica and two destroyers, were independently stationed in the Barents Sea to provide distant cover.[2]

Operation Regenbogen

[edit]On 31 December, a German force, based along the Altafjord in northern Norway, under the command of Vice-Admiral Oskar Kummetz, on Admiral Hipper set sail in Unternehmen Regenbogen (Operation Rainbow). After Convoy PQ 18, the force had waited to attack the next Arctic convoy but their temporary suspension by the British during Operation Torch in the Mediterranean and Operation FB, the routing of single ships to Russia, had provided no opportunity to begin the operation.[3] The force comprised the heavy cruisers Admiral Hipper, Lützow (formerly Deutschland), and the destroyers Friedrich Eckoldt, Richard Beitzen, Theodor Riedel, Z29, Z30 and Z31.[4]

Prelude

[edit]Convoy JW 51B sailed from Loch Ewe on 22 December 1942 and met its escort off Iceland on 25 December. From there the ships sailed north-east, meeting severe gales on 28–29 December that caused ships of the convoy to lose station. When the weather moderated, five merchantmen and the escorts Oribi and Vizalma were missing and Bramble was detached to search for them. Three of the stragglers rejoined the following day and the other ships proceeded independently towards Kola Inlet.[5] On 24 December the convoy was sighted by German reconnaissance aircraft and from 30 December was shadowed by U-354 (Kapitänleutnant Karl-Heinz Herbschleb).[6] When the report was received by the German Naval Staff, Kummetz was ordered to sail immediately to intercept the convoy. Kummetz split his force into two divisions, led by Admiral Hipper and Lützow, respectively.[7]

Battle

[edit]

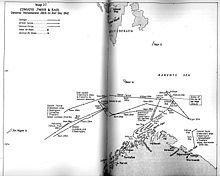

At 08:00 on 31 December, the main body of Convoy JW 51B, twelve ships and eight warships, were some 120 nmi (220 km; 140 mi) north of the coast of Finnmark heading east. Detached from the convoy were the destroyer Oribi and one ship, which took no part in the action; 15 nmi (28 km; 17 mi) astern (north-east) of the convoy Bramble was searching for the stragglers. To the north of the convoy, about 45 nmi (83 km; 52 mi) off, was Vizalma and another ship, while Burnett's cruisers were 15 nmi (28 km; 17 mi) to the south-east, 30 nmi (56 km; 35 mi) from the convoy. To the east, 150 nmi (280 km; 170 mi) away, the home-bound Convoy RA 51 was heading west. To the north of the convoy, Admiral Hipper and three destroyers were closing and 50 nmi (93 km; 58 mi) away Lützow and her three destroyers were closing from the south. At 08:00 the destroyer Friedrich Eckholdt sighted the convoy and reported it to Admiral Hipper.[8]

At 08:20 on 31 December, Obdurate, stationed south of the convoy, spotted three German destroyers to the rear (west) of the convoy. Then, Onslow spotted Admiral Hipper, also to the rear of the convoy and steered to intercept with Orwell, Obedient and Obdurate. Achates was ordered to stay with the convoy and make smoke. After some firing, the British ships turned, apparently to make a torpedo attack. Considerably outgunned, Sherbrooke knew that his torpedoes were his most formidable weapons; the attack was a feignt as once the torpedoes had been launched their threat would be gone. The ruse worked, Admiral Hipper temporarily retired, since Kummetz had been ordered not to risk his ships. Admiral Hipper returned to make a second attack, hitting Onslow causing severe damage and many casualties including 17 killed. Onslow survived the damage but Sherbrooke had been badly injured by a large steel splinter and command passed to the captain of Obedient.[9]

Admiral Hipper then pulled north of the convoy, stumbled across Bramble, a Halcyon-class minesweeper, Admiral Hipper returned fire with her much heavier guns causing a large explosion on Bramble. The destroyer Friedrich Eckholdt was ordered to finish off Bramble, which sank with all hands, while Admiral Hipper shifted aim to Obedient and Achates to the south. Achates was badly damaged but continued to make smoke until eventually she sank, the trawler Northern Gem rescuing many of the crew. The Germans reported sinking a destroyer but this was a mistaken identification of Bramble; they had not realised Achates had been hit.[10]

The shellfire attracted the attention of Force R, which was still further north. Sheffield and Jamaica approached unseen and opened fire on Admiral Hipper at 11:35, hitting her with enough six-inch shells to damage (and cause minor flooding to) two of her boiler rooms, reducing her speed to 28 kn (52 km/h; 32 mph). Kummetz initially thought that the attack of the two cruisers was coming from another destroyer but upon realising his mistake, he ordered his ships to retreat to the west. In another case of mistaken identity, Friedrich Eckholdt and Richard Beitzen mistook Sheffield for Admiral Hipper and after attempting to formate with the British ships, Sheffield opened fire, Friedrich Eckholdt broke in two and sank with all hands.[11]

Lützow approached from the east and fired ineffectively at the convoy, still hidden by smoke laid by Achates. Heading north-west to join Admiral Hipper, Lützow also encountered Sheffield and Jamaica, which opened fire. Coincidentally, both sides decided to break off the action at the same time, each side fearing imminent torpedo attacks by destroyers upon their cruisers. This was shortly after noon; Burnett with Force R shadowed the German ships at a distance until it was evident that they were retiring to their base, the ships of the convoy re-formed and continued towards Kola Inlet.[12]

Aftermath

[edit]

The encounter took place in the middle of the months-long polar night and both the German and British forces were scattered and unsure of the positions of the rest of their own forces, much less those of their opponent. The battle became a rather confused affair and sometimes it was not clear who was firing on whom or how many ships were engaged. Despite the German efforts, all 14 of the merchant ships reached their destinations in the USSR undamaged.[13]

Hitler was infuriated at what he regarded as the uselessness of the surface raiders, seeing that the initial attack of the two heavy cruisers was held back by destroyers before arrival of the two light cruisers. There were serious consequences; this failure nearly made Hitler enforce a decision to scrap the surface fleet and order the German Navy to concentrate on U-boat warfare. Admiral Erich Raeder, commander in chief of the Kriegsmarine, offered his resignation, which Hitler accepted. Raeder was replaced by Admiral Karl Dönitz, the commander of the U-boat fleet.[14]

Dönitz saved the German surface fleet from scrapping, although Admiral Hipper and the the light cruisers Emden and Leipzig were laid up until late 1944; repairs and rebuilding of the battleship Gneisenau were abandoned. Work to complete the aircraft carrier Graf Zeppelin, was suspended for the second and final time. German E-boats continued to operate off the coast of France, only one more big surface operation was executed after the battle. This was the attempted raid on Convoy JW 55B by the battleship Scharnhorst.[15] The battleship was sunk by a British force in what became known as the Battle of the North Cape.[16]

Victoria Cross

[edit]Captain Robert Sherbrooke was awarded the Victoria Cross. He acknowledged that it had really been awarded in honour of the whole crew of Onslow. In the action he had been badly wounded and he lost the sight in his left eye.[17] He returned to operations and retired from the navy in the 1950s with the rank of rear-admiral.[citation needed]

Commemoration

[edit]At the memorial for Bramble, Captain Harvey Crombie said of the crew

They had braved difficulties and perils probably unparalleled in the annals of the British Navy, and calls upon their courage and endurance were constant, but they never failed. They would not have us think sadly at this time, but rather that we should praise God that they had remained steadfast to duty to the end.[18]

The battle was the subject of the book 73 North by Dudley Pope and the poem JW51B: A Convoy by Alan Ross, who served on Onslow.[19]

Allied order of battle

[edit]Close escort

[edit]| Name | Flag | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMS Bramble | Halcyon-class minesweeper | 22–29 December | |

| HMS Hyderabad | Flower-class corvette | 22 December – 3 January | |

| HMS Rhododendron | Flower-class corvette | 22 December – 3 January | |

| HMT Vizalma | ASW trawler | 22 December – 3 January | |

| Northern Gem | ASW trawler | 22 December – 3 January |

Fighting destroyer escort

[edit]| Name | Flag | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMS Achates | A-class destroyer | 25 December – 3 January | |

| HMS Obdurate | O-class destroyer | 25 December – 3 January | |

| HMS Obedient | O-class destroyer | 25 December – 3 January | |

| HMS Onslow | O-class destroyer | 25 December – 3 January | |

| HMS Oribi | O-class destroyer | 25–31 December, separated, sailed independently | |

| HMS Orwell | O-class destroyer | 25 December – 3 January |

Force R

[edit]| Name | Flag | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMS Jamaica | Fiji-class cruiser | 27–31 December, from Kola Inlet | |

| HMS Sheffield | Town-class cruiser | 27–31 December, from Kola Inlet | |

| HMS Matchless | M-class destroyer | 27–29 December, from Kola Inlet | |

| HMS Opportune | O-class destroyer | 27–29 December, from Kola Inlet |

German order of battle

[edit]Surface force

[edit]| Ship | Flag | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Admiral Hipper | Admiral Hipper-class cruiser | Sailed 30 December | |

| Lützow | Admiral Hipper-class cruiser | Sailed 30 December | |

| Z16 Friedrich Eckoldt | Type 1934A-class destroyer | Sailed 30 December | |

| Z4 Richard Beitzen | Type 1934-class destroyer | Sailed 30 December | |

| Z6 Theodor Riedel | Type 1934A-class destroyer | Sailed 30 December | |

| Z29 | Type 1936A-class destroyer | Sailed 30 December | |

| Z30 | Type 1936A-class destroyer | Sailed 30 December | |

| Z31 | Type 1936A-class destroyer | Sailed 30 December |

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 312–313.

- ^ Roskill 1962, pp. 291–292.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 296–300.

- ^ Roskill 1962, p. 292.

- ^ Roskill 1962, pp. 291; Woodman 2004, pp. 312–315.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 313.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 315–317.

- ^ Kemp 1993, p. 118.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 318–320.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 321–323.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 323–324.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 324–326.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 317, 327.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Roskill 1960, pp. 89.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 355–375.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 329, 320.

- ^ Bramble 2010.

- ^ Pope 1988, pp. 147–257; Ross 1967, volume.

- ^ a b Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 48.

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 2005, p. 219.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 316.

Bibliography

[edit]- "HMS Bramble 1942". halcyon-class.co.uk. 7 November 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- Kemp, Paul (1993). Convoy! Drama in Arctic Waters. London: Arms and Armour. ISBN 978-1-85409-130-7.

- Pope, Dudley (1988) [1958]. 73 North: The Battle of the Barents Sea (repr. Secker and Warburg ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-43-637752-5 – via Archive Foundation.

- Roskill, S. W. (1962) [1956]. The Period of Balance. History of the Second World War: The War at Sea 1939–1945. Vol. II (3rd impr. ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 174453986.

- Roskill, S. W. (1960). The War at Sea 1939–1945: The Offensive 1st June 1943 – 31st May 1944. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. III. Part I (1st ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 277168049.

- Ross, Alan (1967). "JW 51B: A Convoy (1946)". Poems, 1942–67. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode. OCLC 458952.

- Ruegg, R.; Hague, A. (1993) [1992]. Convoys to Russia: Allied Convoys and Naval Surface Operations in Arctic Waters 1941–1945 (2nd rev. enl. ed.). Kendal: World Ship Society. ISBN 0-905617-66-5.

- Woodman, Richard (2004) [1994]. Arctic Convoys 1941–1945. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5752-1.

Further reading

[edit]Books

- Hinsley, F. H. (1994) [1993]. British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its Influence on Strategy and Operations. History of the Second World War (2nd rev. abr. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630961-7.

- O'Hara, Vincent P. (2004). The German Fleet at War. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute press. ISBN 978-1-59114-651-3.

- Richards, Denis; St G. Saunders, H. (1975) [1954]. Royal Air Force 1939–1945: The Fight Avails. History of the Second World War, Military Series. Vol. II (pbk. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-771593-6. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Rohwer, Jürgen; Hümmelchen, Gerhard (2005) [1972]. Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (3rd rev. ed.). London: Chatham. ISBN 978-1-86176-257-3.

- The Rise and Fall of the German Air Force (repr. Public Record Office War Histories ed.). Richmond, Surrey: Air Ministry. 2001 [1948]. ISBN 978-1-903365-30-4. Air 41/10.

Websites

- Helgason, Guðmundur. "The Type VIIC boat U-354". German U-boats of WWII - uboat.net. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- Kappes, Irwin J. (23 February 2010). "Battle of the Barents Sea". German-Navy.De. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

External links

[edit]- Battle of the Barents Sea — comprehensive article by Irwin J. Kappes

- Coxswain Sid Kerslake of armed trawler "Northern Gem" during Convoy JW.51B and the Battle of the Barents Sea