Affair of Agbeluvoe

| Affair of Agbeluvoe | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Togoland Campaign of the First World War | |||||||

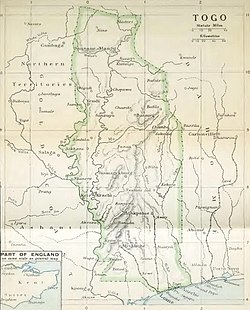

Map of Togoland | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

H. B. Potter H. S. Collins |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,642 | 1,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 83 | 41 | ||||||

| Numbers and casualties relate to personnel in the colonial forces regardless of origin. | |||||||

Map of Togo | |||||||

The Affair of Agbeluvoe ["affair" a military engagement by a force less than a division] (Agbéluvhoé, Beleaguer or the Battle of Tsewie, was fought during the First World War between invading British Empire soldiers of the West African Rifles and German Polizeitruppen (paramilitary police) in German Togoland (now Togo) on 15 August 1914.[a] British troops occupying the Togolese capital of Lomé on the coast, had advanced towards a wireless station at Kamina, 100 mi (160 km) inland on hills near Atakpamé. The only routes inland were by the railway and road, which had been built through dense and almost impassable jungle.

Two trainloads of German troops steamed south to engage the British and delay the Anglo-French invasion but were ambushed at Agbulovhoe, suffered many casualties and fled, leaving 30 mi (48 km) of the railway to the north intact. After a halt of three days to accumulate supplies, the British advance resumed with support from French Tirailleurs Sénégalais. The German colonial forces were capable of only one more defensive action at the Affair of Khra on 22 August. The Germans blew up the wireless transmitter at Kamina on the night of 24/25 August and the colony was surrendered the next day.

Background

[edit]Strategic developments

[edit]An Offensive Sub-Committee of the British Committee of Imperial Defence was appointed on 5 August and established a principle that command of the seas was to be ensured. Territorial objectives were considered if they could be attained with local forces and if the objective assisted the priority of maintaining British sea communications, as British army garrisons abroad were returned to Europe in an "Imperial Concentration". Attacks on German coaling stations and wireless stations were considered to be important, to clear the seas of German commerce raiders. Objectives at Tsingtau, Luderitz Bay, Windhoek, Duala and Dar-es-Salaam were considered and a German wireless station in Togoland, next to the British colony of Gold Coast (now Ghana) on the Gulf of Guinea, was considered vulnerable to attack by local forces.[2]

The high-power wireless transmitter had been built at Kamina and controlled German communication in the Atlantic Ocean, by linking a German transmitter at Nauen near Berlin with German colonies in west Africa and south America. At the outbreak of war, the German acting-Governor of Togoland, who had 152 paramilitary police, 416 local police and 125 border guards but no regular army forces, had proposed neutrality to the British and French colonial authorities under the Congo Act 1885 and then withdrawn from Lomé and the coastal region, when the British demanded unconditional surrender. The acting-Governor, Major Hans-Georg von Doering had sent an un-coded wireless message to Berlin disclosing his plan to retreat to Kamina, which had been intercepted by the British and led to offensive operations against Kamina being authorised by the Colonial Office on 9 August.[3] Anglo-French expeditions from northern Dahomey, Nigeria and the Gold Coast began on 12 August.[4]

Tactical developments

[edit]On 6 August 1914, the British and French governments summoned the German authorities in Togoland to surrender; Anglo-French forces invaded the colony and occupied Lomé unopposed on 7 August and by 12 August, the southern portion of the colony was under Anglo-French control.[5] In northern Togoland British and French troops, police and irregulars occupied Yendi and Mango on 14 August.[6] In the south, the Polizeitruppen had withdrawn to the wireless station at Kamina, about 62 mi (100 km) inland. As British and French forces advanced towards Kamina, the German commanders, acting-Governor Major Hans-Georg von Doering and the military commander, Captain Georg Pfähler attempted to delay the Allied advances by blowing bridges. The main British and French thrusts came from the south, where well built roads and railways from the coast made movement easy for both sides.[7] To harass the West African Rifles of the West African Frontier Force (WAFF), German commanders filled two trains with c. 200 German soldiers and sent them south to raid the Allies on 15 August 1914.[8]

Engagement

[edit]

By 14 August the British had reached Tsevié unopposed and patrols reported the country south of Agbeluvoe clear of German forces. The main British force assembled at Togblekove and "I" Company (Captain H. B. Potter) was sent forward by road to Agbeluvoe, followed by the main body on 15 August. When the main force reached Dawie, civilians reported that a train full of Germans had shot up the station at Tsevié earlier that morning. At Tsevié the British found that the train had steamed north and hurried on to support "I" Company.[9] "I" Company had heard the train run south at 4:00 a.m. while halted on the road near Ekuni. A section was sent to cut off the train and the rest of "I" Company pressed on to Agbeluvoe. A local civilian guided the section to the railway, where Lieutenant H. S. Collins and the section piled stones and a heavy iron plate on the tracks, about 200 yd (180 m) north of the bridge at Ekuni, a village about 6 mi (9.7 km) south of Agbeluvoe and then set an ambush.[10]

A second train, carrying Captain Georg Pfähler, commander of the German forces in Togoland, stopped in front of the obstacle and managed to reverse before the ambushers reached it. The rest of "I" Company had heard the train pass, set another ambush and riddled the engine with bullets as it travelled past at full steam.[10] The British parties rendezvoused and advanced to Agbeluvoe, where another road and rail block was established. Both trains were south of Agbeluvoe and the convoy of carriers with "I" Company's supplies was harassed by German attacks for two hours before they arrived at the British position. The position at Agbeluvoe had been attacked several times from the south; more attacks overnight were repulsed. As the main British force drew close, the Germans retired towards their train and eventually surrendered.[10] The main force under Colonel F. C. Bryant had been engaged by a German party on the afternoon of 15 August at the Lila River, where the Germans blew the bridge and then retired to a ridge where they fought a delaying action holding up the British until 4:30 p.m. Three German dead were left behind; the British lost one man killed and three wounded. When the advance resumed the British reached Ekuni and found twenty railway carriages, which had been derailed by the obstruction near the bridge.[b]

Many of the German soldiers reportedly took off their uniforms, threw down their guns and ran into the bush at the sight of the British ambush.[12] The remaining Germans retreated northwards to Agbeluvoe where further fighting ensued, in which Pfähler was killed.[13][c] A German prisoner wrote an account in September, which described the German force at Agbeluvoe as two companies of local soldiers, commanded by Pfähler.[10] An attempt to break through the "I" Company road and rail block collapsed when the Togolese troops refused orders and then began shooting in all directions. Six Germans were killed including Pfähler, after which the troops fled; the remnants failed to contact Kamina and news of the disaster was eventually delivered by a German train driver who had been fired on at Agbeluvoe.[10]

Next morning Baron Cordelli von Fahnenfeldt, who had designed the wireless station at Kamina and the German explosives expert were captured; the column set off for Agbeluvoe, no news having arrived from "I" Company. Slight opposition was met halfway to the station and much abandoned equipment was found. Firing was heard until about 1 mi (1.6 km) from Agbeluvoe, where most of the c. 200 German troops from the trains were found to have been captured, along with two trains, wagons, a machine-gun, rifles and much ammunition. The Germans who escaped proved too demoralised to conduct demolitions and 30 mi (48 km) of track were taken undamaged. The British lost six killed and 35 wounded, some of whom had injuries which raised suspicions that the Germans had used soft-nosed bullets, which was later discovered to have been partly true, as some hurriedly incorporated reservists had used their civilian hunting ammunition.[14]

Aftermath

[edit]Analysis

[edit]The Germans lost a quarter of their troops in the attempt to use the railway to harass British forces to the south.[15] It was considered a great failure and defeat for the Germans in Togoland. Although it may briefly have delayed the British northward advance, which was not resumed until 19 August, the Affair of Agbeluvoe had no lasting effect on the advance of the Allies. The wireless station at Kamina was demolished by the Germans, which cut off German ships in the South Atlantic from communication with Europe and influenced the Battle of the Falkland Islands (8 December 1914). On 26 August, eleven days after the battle, Doering surrendered. The German force of c. 1,500 men comprising one German and seven Togolese companies, had been expected to be most difficult to defeat, given the terrain and the extensive entrenchments at Kamina. A German prisoner later wrote that few of the Germans had military training, the defences of Kamina had been too large for the garrison to defend and were ringed by hills.[16] The Germans were not able to obtain information about the British in the neighbouring Gold Coast (Ghana) and instructions by wireless from Berlin only insisted that the transmitting station be protected. In the first three weeks of August, the transmitter had passed 229 messages from Nauen to German colonies and German shipping. Defence of the transmitter had wider operational effects but Doering made no attempt at protracted resistance.[17]

Casualties

[edit]The British suffered c. 83 casualties and the German forces c. 41 casualties at the Affair of Agbeluvoe.[18]

Subsequent operations

[edit]On 22 August the Affair of Khra was fought by the Anglo-French invaders and the Germans on the Khra River and in Khra (Chra) village. The German forces had dug in and repulsed the Anglo-French attack. A new attack on 23 August found that the Germans had retired further inland to Kamina. By the end of the campaign, six of seven provinces had been abandoned by the Germans, bridges had not been blown and only the Khra river line among the three possible water obstacles had been defended. The speed of the invasion by several British and French columns, whose size was over-estimated and lack of local support for the colonial regime, had been insuperable obstacles for the German colonialists. Togoland was occupied by the British and French for the duration of the war.[16]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Affair, an action or engagement not of sufficient magnitude to be called a battle. The British Battles Nomenclature Committee Report of 1922 defined a battle as an engagement of at least a corps, an action by at least a division and an affair by a force smaller than a division.[1]

- ^ The train was stopped at Ekuni, where the first train had been derailed by the obstacles that Collins's men had placed on the rails. British forces ambushed the train here and attacked with bayonets.[11]

- ^ Pfähler is buried near the train station at Agbeluvoe along with many German Askari that were killed in the battle.[13]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ BNC 2021, p. 7.

- ^ Moberly 1995, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Strachan 2001, pp. 506–507.

- ^ Corbett 2009, pp. 128–132.

- ^ Moberly 1995, pp. 15–26.

- ^ Moberly 1995, p. 32.

- ^ Strachan 2004, p. 16.

- ^ Moberly 1995, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Moberly 1995, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d e Moberly 1995, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Sebald 1988, p. 602.

- ^ Morlang 2008, p. 36.

- ^ a b Bäumer 2003.

- ^ Moberly 1995, pp. 29–30, 430.

- ^ Friedenwald 2001, pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b Moberly 1995, pp. 34–41.

- ^ Strachan 2001, p. 508.

- ^ Moberly 1995, pp. 29–31, 36–39.

Bibliography

[edit]Books

- Corbett, J. S. (2009) [1938]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (2nd revised, Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Longman. ISBN 978-1-84342-489-5. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- Friedenwald, M. (2001). "Funkentelegrafie Und Deutsche Kolonien: Technik Als Mittel Imperialistischer Politik" [Spark Telegraphy and German colonies: Technology as a Means of Imperialist Policy] (PDF) (in German). Familie Friedenwald. OCLC 76360477. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- Moberly, F. J. (1995) [1931]. Military Operations Togoland and the Cameroons 1914–1916. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence (facs. repr. Imperial War Museum Department of Printed Books and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-235-7.

- Morlang, T. (2008). Askari und Fitafita: "farbige" Söldner in den deutschen Kolonien [Askari and Fitafita: Coloured (sic) Mercenary in the German Colonies] (in German). Berlin: Links. ISBN 978-3-86153-476-1.

- Sebald, P. (1988). Togo 1884–1914: Eine Geschichte Der Deutschen "Musterkolonie" Auf Der Grundlage Amtlicher Quellen [Togo 1884–1914: A History of the Germans' Model Colony on the Basis of Official Sources] (in German). Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-05-000248-4.

- Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. Vol. I. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-926191-8.

- Strachan, H. (2004). The First World War in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925728-7.

- The Official Names of the Battles and Other Engagements Fought by the Military Forces of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914–1919, and the Third Afghan War, 1919: Report of the Battles Nomenclature Committee as Approved by The Army Council Presented to Parliament by Command of His Majesty (pbk. facs. repr. The Naval & Military Press, Uckfield ed.). London: HMSO. 2021 [1922]. ISBN 978-1-78331-946-6.

Websites

- Bäumer, L. (2003). "Kriegsgräber 1914–1918" [War graves 1914–1918] (in German). Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Reynolds, F. J.; Churchill, A. L.; Miller, F. T. (1916). "77". The Cameroons. The Story of the Great War. Vol. III. P. F. Collier & Son. OCLC 397036717.

External links

[edit]- Togoland 1914 Harry's Africa Web 2012

- Funkentelegrafie Und Deutsche Kolonien: Technik Als Mittel Imperialistischer Politik. Familie Friedenwald

- Schutzpolizei uniforms