Banat of Craiova

| Banat of Craiova Banat von Krajowa Banatul Craiovei | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province of the Habsburg monarchy | |||||||||||||

| 1718–1739 | |||||||||||||

The Banat of Craiova shown in the bottom right corner of a French map from 1898 | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Krajowa (Craiova) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1739 | 34,346 families (officially registered) | ||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||

| Ban / Prezes | |||||||||||||

• 1719–1726 | Gheorghe Cantacuzino | ||||||||||||

• 1726–1728 | Georgius Schramm von Otterfels | ||||||||||||

• 1728–1732 | Joachim Czeyka von Olbramowitz | ||||||||||||

• 1732–1733 | J. H. Dietrich | ||||||||||||

• 1733–1739 | Franciscus Salhausen | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern Europe Ottoman–Habsburg wars | ||||||||||||

| 21 July 1718 | |||||||||||||

• Territorial organization | 22 February 1719 | ||||||||||||

• Reorganization | 27 April 1729 | ||||||||||||

| November 1737 | |||||||||||||

| 18 September 1739 | |||||||||||||

| Subdivisions | |||||||||||||

| • Type | Counties | ||||||||||||

| • Units | Dolj, Gorj, Mehedinți, Romanați, Vâlcea | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Romania | ||||||||||||

The Banat of Craiova or Banat of Krajowa (German: Banat von Krajowa; Romanian: Banatul Craiovei), also known as Cisalutanian Wallachian Principality (Latin: Principatus Valachiae Cisalutanae) and Imperial Wallachia (German: Kaiserliche Walachei; Latin: Caesarea Wallachia;[1] Romanian: Chesariceasca Valahie), was a Romanian-inhabited province of the Habsburg monarchy. It emerged from the western third of Wallachia, now commonly known as Oltenia, which the Habsburgs took in a preceding war with the Ottoman Empire—in tandem with the Banat of Temeswar and Serbia. It was a legal successor to the Great Banship of Craiova, with the Wallachian Gheorghe Cantacuzino as its native leader, or Ban. Over the following years, native rule was phased out, and gave way to a direct administration. This provided the setting for Germanization of the bureaucratic elite, introducing the governing methods of enlightened absolutism and colonialism.

Habsburg rule over Oltenia only lasted two decades, which fit within the reign of just one Austrian Emperor (and titular "Prince of Cisalutanian Wallachia"), Charles VI (1711–1740). Its steady encroachment on the privileges of native boyars, as well as its added pressures on the serfs and the free peasants, were highly unpopular, undermining Austrophile positions in Wallachia as a whole. The period witnessed collective tax resistance and internal migration, in an effort to conceal the total number and location of contributors. Charles VI and the Serbian Orthodox Bishops in Belgrade took charge of the Wallachian Diocese of Râmnic, curbing its traditional privileges while allowing it to maintain cultural autonomy. Some timid steps were taken toward Catholicizing Oltenia, with Catholic Bulgarians as the main proxies. Despite being pressured from above, Râmnic Bishops were able to expand their influence into southern Transylvania, providing it with support against the spread of Greek Catholicism.

Popular resistance required a steady adaptation of the administrative apparatus, which included more accurate censuses, relief of some feudal obligations, and heavy penalties for tax offenders. The process was directly supervised by Austrian officials, including Franz Paul von Wallis in the 1730s. It was cut short by an unexpected Ottoman reconquest in late 1737, which brought another devastation of Oltenia, but also witnessed the reestablishment of self-rule by the Romanians. "Imperial Wallachia" formally ended in 1739, when the Ottoman Empire recovered Serbia and Oltenia (which was returned to Wallachia) after the Treaty of Belgrade.

The claim to Oltenia was formally revived during the 1770s by Joseph II, but died out a decade later. The Banat of Temeswar, which became home to a sizable community of Romanian Oltenian and Bulgarian refugees, was kept by the Habsburg monarchy and its successors until 1918. Though rejected by the mass of the people, the Habsburg experiment in Oltenia produced some lasting changes, with some institutions maintained in place by Wallachian Prince Constantine Mavrocordatos. Austrian influence, which introduced the region to organized guilds and a postal system, also provided Wallachians with a linguistic template for modernization and re-Latinization.

History

[edit]Austrian conquest

[edit]The autonomous Banship of Craiova covered a quadrilateral western third of Wallachia, located between the Southern Carpathians to the north, the Danube to the south and west, and the Olt River (Alutus in Latin; hence "Cisalutanian") to the east. Since the 15th century, Wallachia, including its Oltenian subdivision, had been subjugated by the Ottoman Empire (its neighbor to the south), participating as such in the Ottoman–Habsburg wars. During the 17th century, members of the Wallachian boyardom, especially those linked with the Cantacuzino family, began looking to the Habsburgs as potential liberators of the country.[2] The period included several episodes in which Wallachia was declared a Habsburg fief. One such early case was on 7 January 1543, when Radu Paisie, the Prince of Wallachia, nominally attached his country to the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary.[3] In June 1598, during an episodic emancipation from Ottoman vassalage, Prince Michael the Brave and his Postelnic Andronic Cantacuzino (both of whom had served as Bans) submitted Wallachia to the Holy Roman Empire.[4] The Great Turkish War of 1683 saw Prince Șerban Cantacuzino and his Wallachian military forces fighting on the Ottoman side; however, they made a public show of their reluctance, and privately celebrated Habsburg Austria's victory in the Battle of Vienna.[5]

During the 1680s, the Habsburgs were on the offensive, and only their forced participation in the War of the Reunions prevented Wallachia from being conquered at that stage.[6] In August 1716, the Battle of Petrovaradin marked a turning point in the fourth Austro-Turkish War: the Habsburg monarchy chased the Ottoman Army out of Central Europe, and stood to occupy both Wallachia and Moldavia. As a result of this, the Sublime Porte reduced autonomy for Wallachia by introducing a new political elite, the Greek-speaking Phanariotes; Nicholas Mavrocordatos, a Phanariote known for having pacified Moldavia, was brought in to reign as titular Prince of Wallachia.[7] Seeking to undermine the Austrian advance, Ottoman commanders and the Budjak Tatars staged the mass deportation and enslavement of Wallachian peasants—Oltenians were reportedly over-represented in this exodus, as 35,000 evacuees from a total 80,000.[8] The problem was compounded by internal flight, with many more villagers fleeing for safety into the Oltenian forests and the Parâng Massif.[9] As many as 273 Oltenian villages and hamlets were left deserted, from a total 741; 190 of these ghost villages were located in the exposed southern fields.[10] The events notably witnessed the ransacking of Brâncovenești boyar estates, including their manor in Brâncoveni (which had been one of Oltenia's two major military buildings).[11]

As early as March 1716, the Austrians could count on support from an inner faction of Wallachian boyars. Formed around Spătar Radu Leurdeanu Golescu, it regarded Mavrocordatos as a "tyrant".[12] Answering to boyar requests for help, the Habsburg general Stephan von Steinville sent in some hundreds of his soldiers, which, also in August 1716, routed a 3,000-strong Wallachian army at Orșova—according to chronicler Radu Popescu, these troops were secretly opposed to Mavrocordatos, and did not put up a fight. Oltenia was taken whole when the Wallachian Serdar, Cornea Brăiloiu, defected to the enemy, guiding more Austrian troops through the Vulcan Pass and into Târgu Jiu.[13] Some Oltenian boyars were soon co-opted by Prince Eugene of Savoy and his invasion force: Postelnic Ștefan Pârșcoveanu led 200 Habsburg soldiers in battle against the Mavrocordatos troops, at Bengești-Ciocadia.[14] An Austrian force under Stephan Dettine von Pivoda ventured out of Oltenia and into Pitești, then took the Wallachian capital, Bucharest on 14 November, capturing the Prince; during this episode, most Wallachian forces had been diverted to Oltenia, with Popescu invested as Ban.[15] Despite earning support from the Wallachian assembly, which declared itself subject to Emperor Charles VI on 28 November, the Austrians were not confident about establishing a bridgehead in Muntenia, and withdrew immediately after to Mărgineni and Câmpulung.[16]

In December 1716, the Ottomans retook Bucharest and placed John Mavrocordatos on the throne. On 24 February, he obtained from the Austrians recognition as Prince of Wallachia, which was understood to mean only Muntenia; the new ruler also agreed to pay Charles VI a lump tribute in "bags of gold".[17] During the following period, refugee boyars sent Charles several petitions asking for Oltenia to be kept as an autonomous part of the Empire, with its own Voivode, namely Gheorghe Cantacuzino. During this campaign, they expressed alarm that Oltenia would be incorporated with Transylvania, which was in the process of losing its autonomy.[18] The boyar delegations were also mandated to discuss the exclusion of Phanariotes and other Greeks from the table of ranks, which formed the basis of boyar privilege and revenue. They were encouraged in this by Damaschin Voinescu, the Orthodox Bishop of Râmnic, who described Greeks as "betrayers and destroyers of countries".[19]

Boyar appeals were largely ignored by Charles, who added Prince of Cisalutanian Wallachia or Imperial Wallachia (Chesariceasca Valahie) to his list of titles, assigning Steinville to the intermediary position of Supreme Director of Oltenia.[20] The administration was directly organized by a Neo-Acquistic Commission, which answered to the Aulic and War Councils.[21] By August 1717, the Austrians had gained a definitive victory at Belgrade, prompting the Porte to sue for peace. The Treaty of Passarowitz, which was signed on 21 July 1718, recognized Oltenia as an Austrian fief, under uti possidetis.[22] Negotiations were stalled when the Porte instructed its delegates not to admit that Oltenia had been conquered ("under a kind of occupation" was the preferred formula); Austria reacted by bribing Ottoman officials, as well Dutchman Nicolas Theyls and other arbiters, until consensus could finally sway in their favor.[23]

During September 1718, Prince Eugene and Grand Vizier Nevşehirli Ibrahim settled the new border: all Oltenian Danube islands were assigned to the Ottoman Empire, while, on the Olt, Austria kept whatever was west of the thalweg (including islets such as Celieni, Milcovan, Seccediu, and Tuba).[24] Both empires agreed that boyars stranded in Oltenia could keep their estates in Muntenia. The provision was nullified in practice when Princes, beginning with Nicholas Mavrocordatos, identified absentee landlords and confiscated their property. The aggrieved parties sought compensation by urging the Neo-Acquistic Commission to operate in the same way, asking to be handed down the estates of Mavrocordatos loyalists, including the Brâncovenești. The Imperial Revenue Service, which had taken over the estates in question for its own purposes, blocked the attempt.[25] Brâncoveni was taken as spoils of war by Captain Dettine.[26]

Government creation

[edit]The newly conquered region was formally organized through an imperial decree on 22 February 1719. This created an administrative commission in the city of Craiova, which had attributes as a legislative body, executive branch, and local revenue service.[27] As noted by historian Ileana Căzan, Charles VI's court took some pride in having conquered another portion of "Dacia" (and, more specifically, Roman Dacia), which were now politically linked to the reincarnated Roman Empire of the Habsburg realm: "the very conquest of Oltenia was shrouded in the notion of Roman imperial continuity. The boyars, grouped as the Administration, were [also] known as the Dacian senate."[28] The administration also acted as a court, but only heard major criminal offenses (criminalia maiora), property disputes, and some appeals sent in by the first- and second-level courts.[29] Vlach law, generally based on oral records and, more loosely, on the written code Îndreptarea legii, was preserved as the statute, "except for those [provisions] that contradict sound habits".[30] Romanian was still the administrative language. However, the Phanariote infusion of Greek and Turkish terms was immediately curbed, with Latin or German neologisms introduced for the new offices and functions—beginning with the designation of commission members as Consiliari ("Counselors"), assisted by a Secretariu ("Secretary").[31]

As another concession to the locals, the commission was entirely staffed by natives, and allowed its president to use the Wallachian title of Ban. During October 1719, Steinville confirmed the administrative commission, presided upon by Gheorghe Cantacuzino as Ban. Its Council comprised four men: Brăiloiu (who died during the proceedings and was replaced with Staico Bengescu), Golescu, Grigore II Băleanu, and Ilie Știrbei.[32] Its Secretary, Nicolae de Porta, was likewise a Romanian.[33] All staff, including the Ban, were salaried employees of the state; Cantacuzino received 6,000 Reichsthaler annually, and his Counselors 1,000.[34] Steinville's Supreme Directorate was maintained as a supervising body, but remained headquartered in the Transylvanian city of Hermannstadt; until late 1721, Cantacuzino and his commission only had consultative powers.[35] Hermannstadt was also the higher court of appeals, but the population was largely ignorant of its judicial powers, and few sought to obtain its intervention; the commission met more significant competition from the Stabsauditoriat, a military tribunal which had the vaguely defined task of preserving public order, and which took over all penal cases.[36] Frustrating Austrian attempts at modernization, both the Counselors and parties appearing before them agreed to ignore other formalities: several trials were simply held by the Counselors in their private homes, though this was explicitly illegal.[37]

After the Supreme Directorate relinquished its powers, the Ban and his Counselors were assigned control over the administrative network, which was staffed by five Vornici (one per each county) and twenty Ispravnici (one per Plassa).[38] While towns were governed using Județi and Pârgari, villages were directly supervised by Pârcălabi and Vătafi. The latter two categories had been traditionally appointed by their local boyar, but who were now directly picked by, and integrated within, the state apparatus; unlike their superiors and the equivalent urban apparatus, they did not receive salaries, but were exempted from taxation.[39] They were also a first-level judicial power, relieving the Counselors and the Ispravnici of cases such as those involving larceny or minor sexual offences.[40] The boyars were frustrated in their attempt to obtain approval for private armies of Slujitori, which they intended to use against hajduk outlaws; the Austrians "resisted the creation of any national military units, even some of reduced proportions".[41] Instead, the regime maintained collective responsibility, picked up from ancient Wallachian customs, as a deterrent, punishing "ten or twelve surrounding villages" for robbery or murder that went unsolved.[42] For long the only home guard unit tolerated by the Austrians were the 100 Dorobanți of Craiova.[43]

In Oltenia, Austria inherited the Phanariotes' complicated system of taxation, which combined the Ottoman fiscal regime with ancestral duties. The main tribute, or bir, had been owed directly to the Ottoman Sultan; it survived as contrebuțion or dajde împărătească, and was redirected toward the Habsburg Emperor.[44] Collection began in 1720, when each family was expected to pay two Reichsthaler (120 Kreuzer).[45] Various other duties were maintained, and some new ones were introduced. This was the case with the Vorspann, a tribute in horses and transport-related labor collected in lieu of contrebuțion from specific areas—the semi-autonomous region known as Țara Loviștei and villages bordering the main roads. The Vorspann was immediately abused by those in power, who now demanded a permanent supply of horses and labor.[46] The upper classes, including both boyars and some peasants of prestigious lineage (known as aleși or alessi), also received some satisfaction in matters of fiscal policy: most obtained a partial, and some a total, tax exemption from the contrebuțion. However, they were still expected to contribute the "voluntary gift" (donum gratuitum), specifically for the Emperor.[47]

In the aftermath of Passarowitz, Austrian administrators set about repopulating the region, allowing thousands of Muntenian families to settle in the devastated villages, especially those of Gorj and Vâlcea.[48] The Vornici were specifically instructed to drive peasants out of their forest hideouts and back into agricultural life.[49] In 1722, the Austrian conscription census, overseen by the Count of Virmont, estimated Oltenians at 25,000 families, calibrated downward by counts made in 1724 (14,719 families) and 1726 (15,665 families).[50] While re-stabilizing population growth, the Austrian government began looking into increasing the fiscal burden. Contrebuțion goals were set at 190,000 Rheingulden annually, though the target was not consistently met. In 1728, it was raised to some 212,000 Rheingulden, and continued to increase steadily; in 1736, Oltenians provided 260,352 Rheingulden in contrebuțion revenue.[51]

Answering boyar demands, the Austrians put an end to a tacit policy of homesteading, and returned to the status quo of 1716, effectively treating peasants as boyar serfs (rumâni; German: Rumoni).[52] They generally accepted claims that peasants living on boyar- or Church-owned estates also owed corvée, issuing, for the first time in history, written instructions to detail how this duty was to be carried out.[53] Against Wallachian precedents, labor on the estates was legally redefined as an individual, rather than collective, duty, and affixed at one day per week; Austrian authorities limited the number of working days by also forcing farmers to perform statute labor on public works;[54] overall, forced labor in both forms increased greatly, "to as many as fifty-two days a year, as contrasted to three to nine days normal to other parts of Wallachia at the time."[55] Instead, the regime outlawed feudal rent owed in produce (dijmă) for the entire peasant category.[56] It also reacted strongly against boyar claims of "absolute authority" over the serfs, placing the latter under the authority of civil and criminal courts. Overall, "the regulation in agrarian interactions aimed at wholly removing relations between estate-owners and peasants from the realm of the arbitrary, placing them within elaborate and state-controlled formulas."[57] This was also done for humanitarian reasons: one early inspection reported that boyars treated their peasants "like dogs".[58]

Boyar and peasant resistance

[edit]Landowning boyars remained dissatisfied with Austrian policies and alarmed by the fiscal pressures. In 1719, Steinville allowed them a temporary victory by passing regulations that precluded members of their class from selling, as opposed to leasing, land that was deemed "ancestral"; the measure targeted foreign buyers, with a statement of purpose that explicitly mentioned Catholic Bulgarians as the undesirable competitors ("[these] traders are flush with money and will buy up lots of goods, with many of the boyars' villagers opting for refuge in [the Bulgarians'] villages").[59] Bulgarian lobbying obtained that the text be modified to a less xenophobic form, driving the boyars to seek other methods of resistance.[60] One such form was cooperation with native tenant farmers toward nonpayment of the state tax. As early as 1722, there were reports that the Ban and his allies were actively using their administrative functions to undermine tax collectors by "exempting, if not all, then at least most of their own peasants".[61] The boyars were also defeated in their attempt to deny the Bulgarians their judicial autonomy. In October 1727, Charles VI settled the matter by reconfirming that only Bulgarian courts could try Bulgarian cases.[62]

During 1723, tax collectors noted that Dolj County was again missing entire villages, among them Maglavit and Rojiște, their populations having turned nomadic.[63] Two years later, another inspection in Romanați confirmed that 2,300 families had recently gone missing.[64] In Gorj, emigration focused on the Banat of Temeswar, which had no precedent to match Phanariote taxation. This alarmed the War Council: on 12 April 1726, it forbade settlement by non-Catholics.[65] Around that same time, inspector Karl von Tige noted that entire villages of Oltenia were being "placed under the protection of this or that [boyar]".[66] That year witnessed an attempt to contain the phenomenon, combining softer approaches (a de facto ban on corporal punishments for tax-evading peasants)[67] with a more thorough investigation of the boyars' activities. Under the old fiscal regime, boyars estimated their peasants' tax duties, and were not expected to provide an exact count of how many serfs they owned.[68] In early 1727, regulations were introduced by the Aulic Council, which forced the boyars to provide accurate counts of the peasants working on their estates, with tax forms known as fassiones (in Latin) or foi de mărturisanie (in Romanian); heavy fines were introduced where fraud could be ascertained.[69] This measure had the unintended consequence of driving even more peasants into hiding with the boyars' complicity—a "massive dissolving of the contributing masses".[70]

Beginning in September 1725, documents issued by Austrian sources refrained from calling Cantacuzino a Ban, replacing this term with Prezes or Präses (from the Latin Praeses, "governor").[71] Historian Șerban Papacostea sees September 1726 as bringing Oltenian autonomy to a full stop, in that Cantacuzino was deposed and his office eliminated—he was replaced with a President or Prezes, Georgius Schramm von Otterfels, himself succeeded by Joachim Czeyka von Olbramowitz upon his death in late 1728; during that entire interval, Cantacuzino refused to vacate the Ban's manor and accept exile in Transylvania, as had been asked of him.[72] The clampdown on boyar authority was enhanced in 1727, when Tige noted that Cantacuzino's ouster had only reshuffled the governing clique, with the new team of Counselors being "just as zealous in promoting its own interests as the preceding one had been."[73] As Papacostea notes, in the aftermath the Habsburgs introduced not just centralism, but also Germanization, both without curtailing boyar privilege or uprooting traditional society.[74] A centralizing trend was consolidated with an imperial decree on 27 April 1729, whereby the boyars' role in policy-making and their fiscal privileges were greatly reduced, and the Vorspann tax was entirely phased out.[75]

The curtailing was met with protests from Golescu, including one he addressed to the Aulic Council in May 1728, shortly before his death.[76] The continued pressures exercised through the fassiones managed to exhaust boyar resistance, and resulted in more accurate counts of the taxpaying population. 22,000 families were recorded in 1727, rising to 31,000 in 1730; there were at least 34,346 families of any status living in Oltenia in 1739, of whom some 300 were boyar families, and 2,400 were burghers.[77] Oltenia continued to have a sizable population of free-and-landowning peasants—some 47% of the total rural population in 1722.[78] Known as moșneni or megieși in Romanian, possessionati rustici in Latin, and freie Leute in German, these groups remained over-represented in mountainous areas (135 villages in Gorj, 85 in Vâlcea).[79] As part of their conflict with government forces, the boyars obtained that most of the fiscal burden be placed on the moșneni and megieși. In 1727, moșneni families owed the state 10 Rheingulden in contrebuțion (this was marginally reduced to 8.2 Rheingulden in 1728, and remained set at that level for the remainder of Habsburg rule); megieși, meanwhile, had to pay 12–13 Rheingulden per family.[80]

A small group of endogamic families still held on to "great boyar" status. No definitive count was ever provided, but documents read by Papacostea suggest that they ranged between 17 and 24. Examples include the Argetoianus, Băleanus, Bengescus, Brăiloius, Buzescus, Fărcășanus, Glagoveanus, Otetelișanus, Pârșcoveanus, Poienarus, Știrbeis, Urdăreanus, and Zătreanus.[81] They looked down on the lesser boyars, or boiernași, which could include cadet branches of the leading aristocracy (as with the Glagoveanus and Zătreanus), or entire clans fallen into destitution (the Rudeanus).[82] These two classes fully owned 244 villages, or 32% of Oltenian villages.[83] While most boyars of both classes only had one or two villages to their name, the most powerful clans could hold much more. The Brăiloius topped the list, with 28 villages, 16 of them in Gorj.[84]

Austrian consolidation

[edit]A major downside of Austrian rule was Oltenia's removal from the Ottoman economic sphere—specifically, the occupation regime unwittingly blocked much of the cattle, horse, butter and wool trade that had linked Oltenian pastoralists to the markets of Rumelia; wool was mostly redirected toward Transylvania.[85] Similarly, the Austrians slowed down grain and barley production by curbing all exports of cereals, including to other parts of the Monarchy. The latter ban, which was meant to ensure an uninterrupted chain of supply for the Austrian garrisons, was only lifted for a while in 1726.[86] Overall, Oltenia was to remain underpopulated and underdeveloped throughout the Austrian episode. At a "demographic peak" in 1736, the Vornici were still instructed to direct peasants into discarded villagers and resume cultivation in fallow lands.[87]

During 1731, Supreme Director Franz Paul von Wallis suggested "doubling" the Oltenian Vornici with Austrian natives, who would make sure to check the fiscal records and the realities of taxation; this practice was approved by the Aulic Council and introduced during the early months of 1732.[88] In 1735, foreigners Anton Gebaur, Anton Marstaller, Franciscus Nagy and Gaspar Rauch all held offices as Vornici.[89] Meanwhile, all the boyars had been drafted as legal aides, forming Commissions which streamlined judicial procedures and documented cases appearing before the Craiova commission.[90] Also in 1732, J. H. Dietrich took over as President, imposing an Austrian, Johann Wilhelm Vogt, as one of the Oltenian Counselors. Dietrich died in 1733; under his replacement, Franciscus Salhausen, the Council included Vogt and another Austrian man, J. V. Viechtern (the latter as replacement for the Oltenian Grigore Vlasto).[91]

In 1737, the government was almost entirely non-Romanian and non-boyar, with only Ștefan Pârșcoveanu holding on to the office of Counselor.[92] Wallis had asked for his demotion as early as August 1732, but the Aulic Council was adamant in supporting him.[93] Though the Oltenians' Catholicization was not an immediate priority of the Austrian elite, their encouragement of Bulgarian, German, and Hungarian settlement could also double as proselytism—especially after the Diocese of Nicopolis ad Hystrum was relocated to Oltenia.[94] From 1723, the Franciscans began building a church in Râmnicu Vâlcea.[95] Moving the Bulgarians' Catholic see was formalized in June 1725, when Nikola Stanislavič, previously the Catholic Vicar of Wallachia, was anointed Bishop, and took up residence in Craiova.[96] Bulgarians were especially favored by the Austrians, for being "a Catholic population which proved its loyalty during the war against the Turks."[97] From 1729, Stanislavič had tasked his aide Blasius Milli with encouraging the "Paulicians" of Rumelia to settle in Oltenia.[98] As many as 2,000 Catholics from around Nikopol had done so by 1737. Mostly peasants, they formed segregated communities in Craiova and Islaz, distancing themselves from the Bulgarian merchant class.[99] New arrivals included rich Orthodox merchands from Chiprovtsi, including Iova and Iota Iovepali—first attested at Râmnicu Vâlcea in early 1732.[100] Colonization could also include Romanian families, such as a small group from the Budjak, which settled in Costești during November 1732.[101]

Once revived and Germanized, the commission remained largely powerless in tackling boyar and peasant resistance, which often took the form of sabotage and demoralization. As summarized by Papacostea: "the low-ranking Oltenian boyardom still held on to sufficient power so as to block any real application of the imperial commands. [...] Though pushed out of the main offices of the province, though the Craiova Administration was by then directly under Austria's control, the boyars still held on to the administration of counties and villages, which was entirely at their disposal."[102] As he notes, the disgruntled boyars gathered around Ilie Știrbei and Dositei Brăiloiu, whom Czeyka von Olbramowitz had already considered arresting.[103] Faced with such opposition and a parallel sharp rise in outlaw activities, this new administration finally allowed Ispravnici to organize small militias in 1734.[104]

Episodes of mass flight were still occasionally documented, including among the tax-encumbered boiernași: in 1726, the authorities largely failed to collect within this community, whose members "have scattered and are hiding out in the counties".[105] In 1728, 36 villages of Mehedinți were entirely "broken up", while in 1734, Caraula was left with only four moșneni and its Pârcălab.[106] In other cases, the exodus was temporary, with free peasants and serfs taking up seasonal jobs to fulfill their fiscal obligations. In August 1731 for instance, the poorest such peasants were roaming Oltenia to do the mowing on various estates.[107] Overall, members of the upper classes engaged one another in bloodless feuds over the scarce labor resource. Boyars included in the administration were able to outmaneuver their rivals, especially the boiernași, by imposing arbitrary obligations or simply by kidnapping peasants and pushing them into serfdom.[108] During November 1723, Tige reported that the boyars were taking additional steps to prevent inspectors from counting people and animals living on their estates. These opponents were claiming that such counts could only be performed on one's deathbed.[109] Meanwhile, peasants began organizing resistance to the corvée: in 1737, the landlords of Bistrița Monastery noted that none of their tenant farmers had shown up for work, even after obtaining a reduction of their duties.[110]

The Catholic Emperor had uneasy relations with the Orthodox clergy. In 1725, he submitted local churches to the Serbian Bishop in Belgrade, Mojsije Petrović. This grouped Râmnic alongside parishes from the Banat of Temeswar and the purely Serbian Eparchy of Valjevo.[111] In what was a more controversial gesture that drew protests from the monastic community, Charles VI personally appointed Râmnic's Bishops and all the Staretses;[112] he also claimed direct control over the "princely" (domnești) monasteries, from Cozia and Tismana to Polovragi.[113] In 1726, Petrović assigned to Bishopric to a monk Ștefan, who was never consecrated, and whose only contribution as a ktitor was Mihalcea Litterati's church in Ocnele Mari; in late 1727, he was replaced with Inochentie, who remained in charge until 1735.[114]

Monastery administrators soon took the example of boyars in sabotaging Habsburg modernization. Tige's inspection already noted that agricultural production was unusually low on estates held by the Bishopric of Râmnic; during a November 1732 survey, Wallis proposed controlling the village of Orevița by assigning it directly to the Belgrade Bishops.[115] During 1736, an old feudal privilege was abolished at Tismana, with its pastures in Jidoștița being confiscated for use by the Austrian cavalry in Cerneți.[116] The common practice under the Habsburg administration was the collection of all traditional taxes from Orthodox institutions, against tradition—which had either reduced or eliminated such burdens on the Church.[117] In a contrasting move, the Austrians sought to protect church land from boyar encroachment, which had been aggravated after the Mavrocordatos confiscations. In 1726, inspectors were proposing to review all boyar property deeds, to determine how much land had been stolen from the monasteries.[118]

Ottoman reconquest

[edit]The outbreak of a Russo-Turkish War in 1735 was contemplated by the Austrians as an opportunity to complete their expansion into Wallachia. As early as June 1735, Charles VI was preparing another attack on the Ottoman Empire, asking Wallis to ensure that Oltenia would contribute additional revenue for that effort.[119] The prospects of an Austrian annexation were viewed with alarm by the boyars of Bucharest, who were now overwhelmingly Russophile in their outlook, explicitly demanding to be placed under the Russian Empire's protection: "Wallachia's feudal class hoped to obtain Russia's support not just when it came to emancipation from Turkish suzerainty, but also to the territorial reunification, with compensation offered to the Viennese court in exchange for Oltenia."[120] In October 1736, Vornic Preda Drugănescu represented this boyar caucus on a mission to Bila Tserkva. Here, he pledged that Wallachia would surrender only to Russia, and promised to raise the sum needed for the Oltenian purchase, "because all the boyars over there [in Craiova] wish to find themselves under the Russian scepter".[121]

In January 1737, Michael von Talman was mandated by Charles VI to negotiate with Ottoman delegates at Babadag. Here, the Austrians asked for the terms negotiated at Passarowitz, including the recognition of Oltenia as a Habsburg province, to be extended beyond 1782.[122] Oltenia's geopolitical status was changed abruptly in June 1737, when Austria decided to declare war on the Ottoman Empire. The original plan was for a swift annexation of Muntenia, which would have restored Wallachia under Charles's scepter. During the advance from Oltenia and Transylvania, Wallis approached the Phanariote Prince of Wallachia, Constantine Mavrocordatos, with an offer to switch side, promising him recognition as an Austrian vassal in both Muntenia and Oltenia. Mavrocordatos and his court were scandalized by this suggestion, and preferred instead to take refuge in Ottoman-held territory.[123]

Annexation seemed to be realized in on 17 July, when Austrian troops under General Ghillany entered Bucharest.[124] They arrested the boyar regency, sending its members to Transylvania as imperial hostages.[125] At that stage, however, Muntenians were generally unenthusiastic about the change of regimes. Wallis and his men found that most urban centers in both regions had been deserted, and that the fields had been abandoned in full harvest.[126] The situation was aggravated when Wallachians caught hints that Austria intended to break apart Mehedinți, annexing its western half to the Banat of Temeswar.[127] Some boyars, including Constantin Balș, Ștefan Catargiu, and Ștefăniță Ruset, still favored the Austrian option, pledging themselves to Emperor Charles.[128]

As early as August 1737, the Austrians had again moderated their demands: delegates sent to the peace talks at Nemirov were mandated to ask for a new border on the Dâmbovița or the Argeș, preserving Oltenia and dividing Muntenia. These negotiations finally broke down when Austrian delegates accused Russia of intervening in favor of Wallachian territorial integrity.[129] The Ottoman and Wallachian armies subsequently retaliated with a surprisingly efficient counteroffensive. This began in September–October, when Mavrocordatos organized the retaking of Câmpulung and Pitești.[130] On 12 November, Bucharest was recaptured;[131] with a pincer movement, the Ottomans then took Craiova and trapped Charles' troops in northern Oltenia and the Muntenian fort of Perișani,[132] while the Wallachians defeated an Imperial Army in Râmnicu Vâlcea. By December, all of Oltenia was under Wallachian control.[133]

Mavrocordatos reaffirmed his status as Oltenian overlord by sending Radu Comăneanu as his governor in Craiova, and appointing Ioniță Cercedja and his 200 Slujitori to assist against Wallis' army.[134] In the immediate aftermath, Oltenians found themselves encumbered by Ottoman demands, including a tribute set at 300 bags of gold; the Wallachian Kapucu managed to obtain a temporary reduction.[135] The situation proved especially difficult for civilians trapped in the disputed area, who attempted to form their own civilian government under Bishop Climent Modoran. In February 1738, he asked his flock to provide food for both the Ottomans and the Austrians, expressing sympathy for their plight: Știu că va iaste greu a sluji la doi împărați ("I know how difficult it is that you would have to serve two emperors").[136] His own palace in Râmnicu Vâlcea was severely damaged during the Austrians' defense of Oltenia.[137] Throughout the interval, hajduks rallied in the no man's land around Orșova, with outlaws of many nations being joined by a mass of runaway serfs.[138]

During May, Grand Vizier Yeğen Mehmed Pasha presented Austria with an offer to divide Oltenia between the empires.[139] The stalemate was ended only on 18 September 1739, when the Treaty of Belgrade was ratified by Charles VI, who thus recognized Oltenia's re-annexation by Ottoman-vassalized Wallachia.[140] This document unwittingly reopened the dispute between the Ottomans and the Habsburgs over what constituted the western border of Oltenia; it also alienated those of the boyars who had still believed in a Habsburg solution to their problems, "regardless of how difficult adaption to the Habsburgs' administrative and social-juridical system had been".[141] As noted by historians Constantin and Dinu C. Giurescu, nostalgia for Austrian rule was entirely marginal: Wallachian restoration was welcomed with "general joy among both peasants and boyars, who had come to realize that the old regime, whatever its shortcomings, was preferable to Austrian administration".[142]

Legacy

[edit]"Colonial" precedent

[edit]Scholar Daniel Chirot defines Austrian Oltenia as a "premature experiment in modern colonialism".[143] Papacostea views the Austrian episode as the direct confrontation between enlightened absolutism, which "had for a goal the systematic exploitation of [Oltenian] resources", and the traditional "boyar statehood", which claimed a monopoly on peasants' labor. He describes the massive flight of peasants as an instance of class conflict, momentarily successful in defeating the Habsburg government structures, pushing these into "permanent re-adapting".[144] Overall, the experiment implied slowly but steadily adapting the boyar network to the requirements of a centralized system, which required transforming boyars into state functionaries. During this (partly successful) process, Austrian supervisors issued a set of Latin- and Romanian-language protocols, which were meant to standardize boyar activities and limit their sphere of action.[145]

The more overtly colonial aspects of Austrian governance were already dismantled by the 1730s war, when Oltenia became the source of emigration into the Banat of Temeswar. Some pro-Habsburg Romanians joined in this exodus—Diicul (Deicolus) Brăiloiu and George Brediceanu settled around Lugosch; the latter of these two boyars was the patriarch of a noted Romanian Austrian family whose members included Coriolan and Tiberiu Brediceanu.[146] By the 1750s, the authorities had become more tolerant of Gorj immigrants, who settled around Karansebesch as charcoal makers, forming an ethnographic community known as Bufeni.[147] Bulgarian and "Paulician" loyalists also established colonies in Theresiopolis and Stár Bišnov, where they merged into a single ethnic group. Stanislavič, still the community leader, took over as Bishop of Tschanad.[148] Râmnicu Vâlcea was ravaged by the war, pushing the Iovepalis and other Chiprovtsi Bulgarians into permanent exile in Transylvania.[149] By 1746, the city was home to Oltenia's only Bulgarian community, which numbered ten families.[150]

Some of the Habsburg innovations, including the most unpopular ones, were also quickly undone by the Ottomans: "the Austrian work rules in Oltenia were abolished, and such forced labor was stabilized at twelve days a year for most of the century."[151] As noted in 1759 by Ottoman bureaucrat Ahmed Resmî Efendi, the palace of the Ban in Craiova was abandoned, and allowed to fall into disrepair.[152] Such dereliction went in tandem with some institutional continuity, with Wallachian Princes being readily adaptable to modern absolutism. Papacostea highlights the role of Habsburg reforms in shaping similar attempts by Phanariote rulers in the post-1739 era, though also noting that these had "modest means at their disposal, and a much reduced efficiency".[153] Prince Constantine Mavrocordatos, who oversaw Oltenia's readmission into the Wallachian realm, was directly interested in not only preserving absolutist reforms in Oltenia, but also in extending them to other parts of the country, and in expanding their scope. His war on privilege, meant to ensure fiscal stability, led him to pioneer the abolition of serfdom, and to introduce government as a mediator between boyars and peasants.[154] In 1756, the Porte itself reverted on its stances and, imitating the Austrians, proceeded to increase its demands—that year, a "colonial regime similar to that of the Austrian occupation" was introduced, with Wallachians required to contribute specified quotas of barley, flour, and wheat.[155]

Austrian contributions to the Romanian lexis, and to the language of political geography, included the designation of the old Banship as "Oltenia", which was thereafter conceptualized as distinct from Wallachia and Muntenia.[156] The Habsburg claim to this territory was revived by Emperor Joseph II and General von Buccow in the early 1770s, during turmoil caused by the Russo-Turkish War. Citing precedent, as well as a number of records that they had falsified, the Austrians demanded Oltenia, alongside a "Wallachian corner" (vaguely defined parts of Prahova, Buzău, and Râmnicu Sărat); these were to be annexed alongside parts of Moldavia, specifically Bacău and Putna.[157] In July 1771, Sultan Mustafa III agreed to relinquish Oltenia.[158]

The annexation was never carried out, since Russia vouched for Wallachia's territorial integrity; instead, Joseph accepted the northwestern tip of Moldavia, which later became known as "Bukovina".[159] Though his overall plan fell apart, the Austrians embraced a "Dacian" alternative, proposing that Henry of Prussia be made ruler of Moldavia and Wallachia, merged into a buffer state—while still seeking to restore their own "old borders on the Olt".[160] During the 1780s, Joseph's ambitions were frustrated by Russia's Catherine the Great, who embraced the "Dacian" kingdom that she expected would be Russian-friendly. The Austrian court turned its focus on the Adriatic Sea and Bosnia Eyalet; in some projects he vetted, Joseph still considered annexing or purchasing Oltenia as an extension of this southwestern realm.[161] A specific claim to Oltenia was again voiced by the Austrian court during the Oriental crisis of 1783: Joseph announced that he did not regard the Treaty of Belgrade as a renunciation of his rights in Craiova.[162]

An intervention by the Kingdom of France ended mounting hostilities between Russia and Austria, and prevented the Austrian army from staging a march on Craiova; this intervention, which ensured that Joseph "received nothing" from the crisis, also showed the strains of the Franco-Austrian alliance.[163] A 1788 map of Wallachia, done in Vienna by Ferdinand Joseph Ruhedorf, still showed the five Oltenian counties as Valachia Austriaca.[164] The Habsburgs no longer revived the claim in the 19th century. During the Crimean War, the Habsburg state, revived as the "Austrian Empire", intervened as a peacekeeper in both Moldavia and Wallachia. In 1856, Napoleon III unsuccessfully proposed that Austria take over both countries as a unified vassal state, with Francis of Modena on its throne.[165]

The United Principalities were created shortly after, still as an Ottoman subject. This tutelage was eventually cast aside in the Romanian War of Independence of the 1870s. In its wake, the Romanian Assembly of Deputies had to accept the cession of Southern Bessarabia to Russia, in exchange for Northern Dobruja. As an opponent of this trade-off, Romanați assemblyman Nicolae Lăcusteanu argued that Romania's Dobrujan rights were at least as arbitrary as Austrian rights in Oltenia.[166] During the Romanian campaign of World War I, both Muntenia and Oltenia were occupied by the Central Powers, including Austria-Hungary. According to one account, attributed to Constantin Stere, Austria intended to absorb Oltenia in late 1917, and was only stopped from doing so when the international consensus swung against imperialistic annexations.[167]

Cultural survivals

[edit]The Habsburgs' effort toward Catholicizing Oltenia mostly concentrated on reforming the Orthodox Church itself—one such measure was to impose Catholic monastic rules on Orthodox monks.[168] By 1726, Steinville's portrait had been added into frescoes of Sfântul Nicolae Church in Băile Olănești (it was covered up after 1739).[169] The issue of Catholic government in an Orthodox land became intertwined with religious disputes in Transylvania, where the Habsburgs had established a Romanian Greek Catholic congregation, part of the Eastern Catholic Churches. It was partly as a result of Gheorghe Cantacuzino's intervention that Ioan Giurgiu Patachi was elected in 1714 as the second Catholic Primate of Bălgrad.[170] Before his death in 1727, Patachi sought to establish an Eastern Catholic bishopric for Habsburg Oltenia, while seeking to "gather under his watch all of Austria's Romanians".[171] This project never took hold. Instead, in January 1728,[172] Râmnic Bishops were given an exclusive privilege in handling Orthodox life in the southernmost pockets of Transylvania, at a time when most other Orthodox Transylvanians were decreed to have been united with Rome. According to scholar Mihai Săsăujan, this state of affairs was preserved into the 1750s.[173] The situation angered the new Catholic converts: Stefan Olshavskyi, the Vicar of Mukachevo, asked that the Ecumenical Patriarchate refrain from consecrating Orthodox priests anywhere in Transylvania.[174]

The Austrians endorsed teaching in Latin by Orthodox institutions, but with only modest results (such as Antonie Dascălul's school in Craiova); by 1729, the administration was financing a more ambitious project for a Humanistic Gymnasium to be staffed by either Jesuits or Piarists.[175] Overall, Charles VI remained indifferent to cultural battles within the Wallachian Church. This also meant that, unlike the Muntenian hierarchs, there was no stake in protecting Church Slavonic in Oltenia—indirectly helping Bishop Damaschin and others who supported liturgical printing in Romanian. In these circumstances, Râmnicu Vâlcea and its printing press were major contributors to the Orthodox revival taking place in both Oltenia and Transylvania.[176] The authorities were however invested in preventing any dispute between the Eastern Catholic and Orthodox branches of Romaniandom. Historian Radu Nedici notes that Damaschin was "under the strict control of a Habsburg Catholic administration".[177] His one attempt at a polemic was a 1724 tract on the Sacraments, which displeased Patachi and had to be withdrawn from circulation.[178] Nedici and Aurel Dragne both argue that the eventual loss of Oltenia reverberated into Transylvania, leaving its remaining Orthodox congregations submitted by the Serbian Bishopric (though their primacy remained unrecognized by the Austrian court).[179]

Linguist C. Frâncu views Austrian rule in Oltenia as crucial in establishing the canons of modern Romanian as an official language—especially since, at that stage, Romanian was being purged from Austrian legal culture in Transylvania.[180] This implied a first instance of linguistic re-Latinization in Wallachia, codifying terms such as administrație ("administration"), arest ("arrest"), colonel, comandant ("commander"), comisar(iu) ("commissioner"), copie ("copy"), and deputat ("deputy").[181] The 20-years-long existence of an Imperial Wallachia spurred other changes in Romanian society. In some cases, these were to prove long-lasting—one example is the establishment of a regular postal service, which allowed private mail to be sent between Oltenia and Transylvania.[182] In parallel, the administrative commission was awarded its own post riders, or Călărași, who numbered 50 men in 1727, and who ran errands between Craiova and the Vornici.[183]

In 1716, Captain Friedrich Schwantz von Springfels, a mathematician trained at the University of Jena, had uncovered the remains of a Roman road running along the Olt at Cozia. He was therefore able to persuade his superiors that the banks were usable for horse transportation at any time of the year.[184] He described the path leading from Islaz to Râmnicu Vâlcea as Via Trajani, from Trajan.[185] Between 1717 and 1722, Steinville oversaw the construction of Via Carolina, a modernized road linking the Turnu Roșu Pass (and, through it, Transylvania) to Călimănești.[186] In tandem, the authorities also rebuilt and enlarged the passage through the Vâlcan Mountains, linking the Transylvanian mountainous enclave, Țara Hațegului, with Craiova and Vidin.[187]

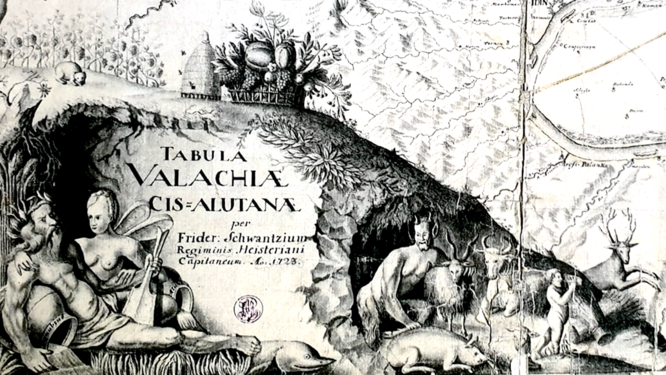

The Austrians were also noted for exploring and cataloguing all features of Oltenian geography. This effort began early on, when Steinville's personal physician, Michael Schendo van der Bech, provided the first description of the mineral waters at Bengești-Ciocadia.[188] One noted contribution was Captain Schwantz's own regional map. Begun on Steinville's orders in 1720,[189] it endures as an "incomparable instrument of research", the "first cartographic record of all human settlements in Oltenia".[190] In keeping with Austria's imperial and "Dacian" ideology, the work is noted for attempting to record all Roman-era ruins known in the 1720s.[191] The minuteness of Schwantz's contribution was made possible by his direct involvement in surveying Oltenia. In 1738, Stefan Lutsch von Luchsenstein copied Schwantz's map into his general map of Wallachia; the Muntenian portions were based on highly inexact Ottoman depictions, making the result unusable in practice.[192]

The attempted economic revival, which remained bound to the ideology of mercantilism,[193] was also backed by monetary stabilization. The circulation of devalued Wallachian coins, Kreuzer, and Ottoman pare, was tolerated, while the circulation of bullion was centered on the Reichsthaler. The authorities attempted in vain to block the circulation of kuruşlar in Oltenia, since these were still the most frequent payment for regional exports.[194] As part of the recolonization and re-monetization drive, Austrians revived or created agricultural shows (notably at Tâmna and Cerneți), though making sure that commercial activities of this kind were subject to price controls (called narturi).[195] Austria also recognized and enforced urban privileges as codified in the Wallachian tradition. As noted by Papacostea, doing so effectively delayed town development, especially by preventing the rural-to-urban migration.[196] Urbanization stalled, including in Craiova. The Banship's capital remained "in a rather semi-agrarian phase"[197] and, a hundred years after its Wallachian reconquest, still gave the impression of an "immense bazaar".[198]

Austrian commercial innovations included Craiova's Spițăria Împărătească, the first-ever pharmacy to have been set up in the Romanian lands (operating 1718–1730).[199] From 1719, the city's administration noted that Oltenian guilds existed largely on paper, with ill-defined areas of control. They presented the population with an option between full regulation and free trade; it chose the former, resulting in the establishment of a chartered Guild of Chandlers and Soapers in August 1725.[200] Imperial envoys overrode boyar resistance when they allowed Bulgarians and Greeks to form their respective trade emporiums; the boyars mounted additional resistance when Oltenian Romanians petitioned to set up their own company, arguing that Romanians were not producing trade goods for export.[201] The Austrian regime attempted to reform the status of Rudari slaves used for gold panning by the monks of Cozia, reemploying them as salaried workers of the state. A Chamber of Gold was instituted with the purpose of clamping down on gold contraband.[202] Habsburg envoys tolerated the use of slave labor in the Oltenian salt mines (principally those of Ocnele Mari), but introduced new extraction and refining techniques. Their attempt to recover these investments drove up the price of salt, losing consumers to the coarser, but cheaper, salt of Ottoman Muntenia.[203]

Symbols

[edit]Heraldists from the Holy Roman Empire had traditionally used a lion to represent kleine Walachey ("Little Wallachia"), which, from the 16th century, generally meant the Craiova Banship. These were attributed arms, which had no local correspondent, and may have originally stood for "Dacia" or "Cumania"; the lion was apparently never used by the Bans, and neither was it taken up by the Austrian administration.[204] Before 1718, local Bans used some symbols of their own, which are attested, but not described, by contemporary sources. In the mid 17th century, Mareș Băjescu had a grapă, adecă steag bănesc ("grapă, which is to say a Ban's flag") brought in for his ceremonial investiture in Craiova.[205] Historian Ion Donat reports that the region also had its own badge, separate from the Wallachian seal, and its own flag, at least as early as the 1500s.[206] Theologian Irineu Popa argues that flags used by the Bans showed Demetrius of Thessaloniki, who is still the patron saint of Craiova.[207]

In its early years, Imperial Wallachia used a variant of the standard Wallachian seal;[208] this symbol can be found in the bottom right corner of Schwantz von Springfels' 1723 map.[209] Also in 1723, this all-Wallachian emblem was replaced with a complex seal depicting the double-headed Reichsadler displaying the Wallachian bird.[210] According to a roll of arms created by Radu Cantacuzino, the same arrangement was used as the personal arms of his brother, Ban Gheorghe.[211] The Reichsadler, a familiar presence on the Austrian border markers, became known locally as Zgripțor. The same term was used as a by-word for Habsburg rule and its officials.[212]

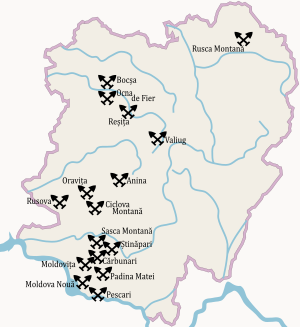

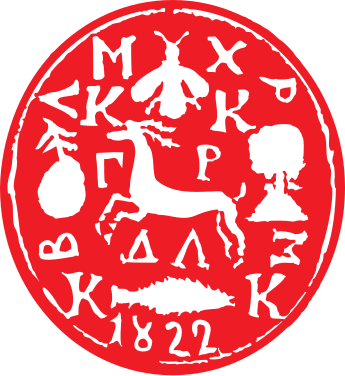

In their effort to modernize the administration, Austrian authorities banned the usage of private insignia on official documents. Instead, they regulated corporate heraldic seals for each of the five Oltenian counties. These referred to the main economic contribution of each Oltenian subdivision: Dolj had a fish; Gorj—a deer; Mehedinți—a beehive; Romanați—an ear of corn; and Vâlcea—a fruit-bearing tree.[213] According to historian Dan Cernovodeanu, these symbols, though not attested in writing before 1719 (and first appearing in visual form as a companion to Schwantz's 1723 map), were locally made, and likely predated the Austrian occupation.[214] They were also largely preserved into the later seals of Oltenian Bani and Caimacami, into the early 19th century.[215]

-

Heraldic allegory of Oltenian counties, in Schwantz von Springfels' 1723 map of the region

-

Arms used by Gheorghe Cantacuzino

-

Seal used by Oltenian Caimacam Nicolae Scanavi in 1813, showing the county symbols

-

County symbols on Caimacam Constantin Câmpineanu's seal, 1822

Notes

[edit]- ^ Lazăr, p. 81

- ^ Papacostea, p. 17

- ^ Marian Coman, "A Game of Rhetoric. Transylvanian Regional Identities in Medieval Wallachian Sources", in Annales Universitatis Apulensis. Series Historica, Vol. 16, Issue II, 2012, p. 92

- ^ Radu Ștefan Vergatti, "Mihai Viteazul și Andronic Cantacuzino", in Argesis. Studii și Comunicări, Seria Istorie, Vol. XXII, 2013, pp. 80, 83–85

- ^ Abrudan, pp. 61–63

- ^ Abrudan, pp. 64–65

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 13–17

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 33–36

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 54–55

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 35, 167

- ^ Drăghiceanu, pp. 57, 63

- ^ C. Tamaș, pp. 68–69

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 17–18. See also Abrudan, pp. 69–70; C. Tamaș, p. 68

- ^ Cioarec, p. 92. See also C. Tamaș, p. 68

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 18–20; C. Tamaș, pp. 69–70

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 20–21. See also Abrudan, p. 70; Căzan, p. 192; C. Tamaș, p. 70

- ^ Abrudan, pp. 70–71; Papacostea, pp. 20–22

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 23–28. See also C. Tamaș, p. 70; Vianu, p. 19

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 152–153

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 28, 286

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 28–29

- ^ Abrudan, pp. 71–74; Papacostea, p. 22

- ^ Abrudan, pp. 72–73

- ^ Abrudan, p. 74

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 149–150

- ^ Drăghiceanu, pp. 63, 72

- ^ Papacostea, p. 253

- ^ Căzan, p. 199

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 274–277

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 285–287

- ^ Frâncu, pp. 308–309

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 153–154, 252. See also C. Tamaș, p. 70

- ^ Frâncu, p. 308

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 261–262

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 252–252

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 277, 280–282

- ^ Papacostea, p. 275

- ^ Papacostea, p. 253

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 253–254, 258, 262–263

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 271, 274, 284–285. See also V. Tamaș, pp. 120–121

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 255–256

- ^ Papacostea, p. 285. See also V. Tamaș, p. 120

- ^ Papacostea, p. 256

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 224–229

- ^ Papacostea, p. 228

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 237, 248–249, 256

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 154–158, 166, 234–236

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 36–46

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 55–57

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 47, 227

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 228–229

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 60–65, 170–193

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 170–182, 197–198, 201–212

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 170–182, 197–198, 204–205

- ^ Aksan, p. 68

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 205–210

- ^ Papacostea, p. 273

- ^ Papacostea, p. 271

- ^ Papacostea, p. 151

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 151–152

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 47–48

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 279–280. See also Ciocîltan, p. 77

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 58–59

- ^ Papacostea, p. 59

- ^ Gaga, p. 123

- ^ Papacostea, p. 48

- ^ Papacostea, p. 60

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 229–230

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 49–51, 229–230

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 48–49

- ^ Frâncu, p. 308

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 253, 265

- ^ Papacostea, p. 265

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 32, 153–154, 252–253

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 266–268

- ^ C. Tamaș, pp. 70–71

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 51–52, 143

- ^ Aksan, p. 84

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 196–197

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 232–234

- ^ Papacostea, p. 163

- ^ Papacostea, p. 164

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 167–168

- ^ Papacostea, p. 168

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 91–96

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 96–104

- ^ Papacostea, p. 69

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 269–270; V. Tamaș, p. 122

- ^ V. Tamaș, pp. 123–125

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 277–279

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 253, 267–268. See also Cioarec, p. 93

- ^ Cioarec, p. 93; Papacostea, pp. 252–253, 268

- ^ Cioarec, p. 93

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 297–298. See also Călin & Oanță, pp. 331–332

- ^ Lazăr, p. 82

- ^ Călin & Oanță, pp. 329–332

- ^ Ciocîltan, p. 77

- ^ Călin & Oanță, pp. 330–331

- ^ Ciocîltan, pp. 77–78

- ^ Lazăr, pp. 81–82

- ^ Cioarec, p. 93

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 268–269

- ^ Papacostea, p. 268

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 255–256

- ^ Papacostea, p. 163

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 59, 219

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 196–197

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 198–200, 214–219, 265–266

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 210–211

- ^ Papacostea, p. 210

- ^ Cilibia, pp. 176–178

- ^ Vilibia, pp. 177–178. See also Theodorescu, p. 142

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 289–297

- ^ Theodorescu, p. 142

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 70–71

- ^ Donat, p. 113

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 157–163

- ^ Papacostea, p. 150

- ^ Lisnic, p. 114

- ^ Vianu, pp. 19–20. See also Pogăciaș, p. 340

- ^ Vianu, pp. 21–22

- ^ Lisnic, p. 117

- ^ Lisnic, p. 116. See also Vianu, p. 23

- ^ Lisnic, p. 116. See also Papacostea, p. 305; Vianu, p. 23

- ^ Vianu, pp. 23–24

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 307–309

- ^ Lisnic, pp. 115–116

- ^ Lisnic, pp. 119–120

- ^ Lisnic, pp. 117–119; Pogăciaș, pp. 341–342

- ^ Lisnic, p. 120; Pogăciaș, p. 343

- ^ Lisnic, p. 120

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 305–306, 309

- ^ Pogăciaș, p. 343

- ^ Lisnic, p. 120

- ^ Lisnic, p. 123

- ^ Papacostea, p. 309

- ^ Theodorescu, pp. 142–143

- ^ Aksan, p. 68

- ^ Lisnic, pp. 123–124

- ^ Lisnic, pp. 123–126; Papacostea, p. 306; Pogăciaș, pp. 345–347

- ^ Lisnic, pp. 125–126

- ^ Frâncu, p. 307

- ^ Aksan, p. 68

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 10–11

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 257–261

- ^ A. Peteanu, "Din trecutul Lugojului. O pagină de istorie românească: Familia Brediceanu", in Dacia. Ziarul de Afirmare Românească al Ținutului Timiș, Issue 79/1939, p. 8

- ^ Gaga, pp. 123–126

- ^ Călin & Oanță, pp. 332–339

- ^ Lazăr, p. 83

- ^ Ciocîltan, p. 78

- ^ Aksan, p. 68

- ^ Aksan, pp. 70–71

- ^ Papacostea, p. 270

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 310–320. See also Aksan, pp. 68–69

- ^ Aksan, p. 69

- ^ Erwin Gáll, Réka Fülöp, Mihály Huba Hőgyes, "'Periferiile periferiilor'? Fenomen arheologic sau stadiul cercetării: de ce nu au fost descoperite necropole din perioada secolelor VIII‒X în Transilvania estică și centrală, respectiv în nordul și centrul Olteniei și Munteniei?", in Sorin Forțiu (ed.), ArheoVest, Nr. VIII: In Honorem Alexandru Rădulescu, Interdisciplinaritate în Arheologie și Istorie, Timișoara, noiembrie 2020, Vol. 1: Arheologie, p. 388. Timișoara & Szeged: Arheovest & JATEPress, 2020. ISBN 978-963-315-465-6

- ^ Iorga (1938), pp. 11–12. See also David, p. 67

- ^ David, p. 67; Iorga (1938), pp. 15, 19, 26

- ^ David, pp. 68–69; Iorga (1938), pp. 25–30

- ^ David, p. 68

- ^ Grigorovici, p. 298. See also David, p. 69

- ^ Grigorovici, pp. 305–306

- ^ Grigorovici, pp. 315–317

- ^ Jean-Yves Guiomar, Marie-Thérèse Lorain, "La carte de Grèce de Rigas et le nom de la Grèce", in Annales Historiques de la Révolution Française, Issue 319, January–March 2000, pp. 101–125

- ^ Cosmin Lucian Gherghe, Emanoil Chinezu – om politic, avocat și istoric, p. 102. Craiova: Sitech, 2009. ISBN 978-606-530-315-7

- ^ Constantin Sarry, Regele Carol I, Dobrogea și dobrogenii. Conferință ținută în ziua de 10 Mai 1915, la Hârșova, pp. 11–12. Bucharest: Institut de Arte Grafice Speranța, 1915

- ^ Alexandru Marghiloman, Note politice, Vol. 2. 1916–1917, pp. 511–512. Bucharest: Editura Institutului de Arte Grafice Eminescu, 1927

- ^ Cilibia, p. 176

- ^ Theodorescu, p. 142

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 191–192

- ^ Iorga (1921), p. 192

- ^ Dragne, pp. 62–63

- ^ Mihai Săsăujan, "Atitudinea cercurilor oficiale austriece față de românii ortodocși din Transilvania, la mijlocul secolului al XVIII-lea, în baza actelor Consiliului Aulic de Război și a rapoartelor conferințelor ministeriale din Viena", in Annales Universitatis Apulensis, Series Historica, Vol. 11, Issue II, 2007, pp. 234, 247–248

- ^ Iorga (1921), p. 193

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 299–300

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 298–299. See also Ioan I. Ică jr., "Vechea traducere românească uitată a Sinodiconului Ortodoxiei", in Revista Teologică, Vol. XXVI, 2016, pp. 221–222; Nedici, pp. 187–189, 196–197

- ^ Nedici, p. 196

- ^ Dragne, p. 63; Nedici, pp. 196–197

- ^ Dragne, pp. 67–68; Nedici, pp. 203–208

- ^ Frâncu, pp. 307–308

- ^ Frâncu, passim

- ^ Papacostea, p. 125; V. Tamaș, p. 119

- ^ Papacostea, p. 255

- ^ Zsigmond Jakó, Köleséri Sámuel tudományos levelezése (1709–1732), p. 55. Cluj-Napoca: Societatea Muzeului Ardelean, 2012. ISBN 978-606-8178-52-3

- ^ Căzan, p. 198

- ^ Căzan, pp. 198–199; Papacostea, pp. 124–125

- ^ Nicolae Popa, "Hațeg, un pays fondateur de la Roumanie. L'evolution de ses voies de communication", in the Review of Historical Geography and Toponomastics, Vol. I, Issue 1, 2006, p. 84

- ^ Samarian, p. 118

- ^ Căzan, pp. 196–197

- ^ Papacostea, p. 33

- ^ Căzan, p. 199

- ^ Căzan, pp. 199–200

- ^ Papacostea, p. 131

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 127–141

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 109–116

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 115–118

- ^ Cristina Șoșea, "Spatial Dynamics of Craiova Municipality. Transformation of the City's Relation with Its Peripheries", in Analele Universității din Oradea. Seria Geografie, Vol. XXIII, Issue 2, 2013, p. 377

- ^ Violeta-Anca Epure, "Aspecte de viață urbană în Principatele Române surprinse de consulii și voiajorii francezi prepașoptiști. Oraşele din Țara Românească (I)", in Terra Sebus. Acta Musei Sabesiensis, Vol. 11, 2019, p. 217

- ^ Samarian, pp. 173–174

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 84–86

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 120–123

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 90–91, 106

- ^ Papacostea, pp. 86–88, 104–106

- ^ Cernovodeanu, p. 78

- ^ Donat, p. 181; Oprea Gh. Petre, "Craiova dealungul veacurilor", Vol. VIII, Issue 374, March 1934, in Realitatea Ilustrată, p. 21

- ^ Donat, p. 185

- ^ Irineu Popa, "Biografii Luminoase: Sfântul Mare Mucenic Dimitrie, darul lui Dumnezeu pentru olteni. Izvor de har și punte peste veacuri", in Revista Ortodoxă, Issue 3/2017, p. 8

- ^ V. Tamaș, p. 121

- ^ Căzan, p. 197

- ^ V. Tamaș, p. 121

- ^ Sorin Iftimi, Vechile blazoane vorbesc. Obiecte armoriate din colecții ieșene, pp. 114, 124, 130. Iași: Palatul Culturii, 2014. ISBN 978-606-8547-02-2

- ^ Căzan, pp. 192–193

- ^ V. Tamaș, pp. 121–122

- ^ Cernovodeanu, pp. 185–186, 440–441

- ^ Ioan V. Câncea, "Sigiliile caimacamilor Craiovei", in Revista Arhivelor, Issues 6–7, 1936–1937, pp. 178–179. See also Cernovodeanu, pp. 450–453

References

[edit]- Mircea-Gheorghe Abrudan, "Politica orientală a Imperiului Habsburgic între asediul Vienei (1683) și Tratatul de Pace de la Passarowitz (1718)", in Astra Salvensis, Vol. IV, Issue 8, 2016, pp. 61–75.

- Virginia H. Aksan, "Whose Territory and Whose Peasants? Ottoman Boundaries on the Danube in the 1760s", in Frederick F. Anscombe (ed.), The Ottoman Balkans, 1750–1830, pp. 61–86. Princeton: Markus Weiner Publishers, 2006. ISBN 1-55876-383-X

- Claudiu Sergiu Călin, Marius Oanță, "Nikola Stanislavich — Episcop de Nicopole ad Hystrum (1725–1739) și Episcop de Cenad (1739–1750)", in Banatica, Vol. 24, Issue 2, 2015, pp. 327–342.

- Ileana Căzan, "Cartografia austriacă în secolul al XVIII-lea (1700–1775). Caracteristici și reprezentanți", in Revista Istorică, Vol. XIV, Issues 3–4, May–August 2002, pp. 191–206.

- Dan Cernovodeanu, Știința și arta heraldică în România. Bucharest: Editura științifică și enciclopedică, 1977. OCLC 469825245

- Constantin Cilibia, "Arhimandritul Petronie din Timișoara, stareț la Mănăstirea Segarcea", in Mitropolia Olteniei, Vol. LXVIII, Issues 9–12, September–December 2016, pp. 172–184.

- Ileana Cioarec, "Mari dregători din neamul boierilor Pârșcoveanu", in Anuarul Institutului de Cercetări Socio-Umane C. S. Nicolăescu-Plopșor, Vol. XIII, 2012, pp. 90–95.

- Alexandru Ciocîltan, "The Identities of the Catholic Communities in the 18th Century Wallachia", in Revista Română de Studii Baltice și Nordice. The Romanian Journal for Baltic and Nordic Studies, Vol. 9, Issue 1, 2017, pp. 71–82.

- Gheorghe David, "1782: Ecaterina II, Potemkin și... regatul Daciei", in Magazin Istoric, September 1991, pp. 66–69.

- Ion Donat, Domeniul domnesc în Țara Românească (sec. XIV–XVI). Bucharest: Editura enciclopedică, 1996. ISBN 973-454-170-6

- Virgil Drăghiceanu, "Curțile domnești brâncovenești. IV. Curți și conace fărâmate", in Buletinul Comisiunii Monumentelor Istorice, Vol. IV, 1911, pp. 49–78.

- Aurel Dragne, "Biserică și societate în secolul al XVIII-lea. Situația clerului român din Țara Făgărașului", in Acta Terrae Fogarasiensis, Vol. V, 2016, pp. 53–88.

- C. Frâncu, "Neologisme juridico-administrative în documentele din Oltenia din timpul administrației austriece (1718–1739). I", in Studii și Cercetări Lingvistice, Vol. XXXVI, 1985, pp. 307–319.

- Lidia Gaga, "Costum de enclavă. Costum de contact. Bufenii", in Analele Banatului. Etnografie – Artă, Vol. II, 1984, pp. 123–141.

- Al. Grigorovici, "Crisa orientală din 1783 și politica Franciei", in Revista Istorică, Vol. XXIV, Issues 10–12, October–December 1938, pp. 293–321.

- Nicolae Iorga,

- "Dări de seamă. Silviu Dragomir, Istoria desrobirii religioase a Românilor din Ardeal în secolul al XVIII-lea", in Revista Istorică, Vol. VII, Issues 7–9, July–September 1921, pp. 190–201.

- Românismul în trecutul Bucovinei. Bucharest: Metropolis of Bukovina, 1938.

- Gheorghe Lazăr, "Aux frontières du grand commerce. La famille Iovipali en Valachie (XVIIIe—dèbut du XIX e siècle)", in Lora Taseva, Penka Danova (eds.), Югоизточна Европа през вековете: социална история, езикови и културни контакти. Studia Balcanica 35, pp. 79–100. Sofia: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 2021. ISBN 978-619-7179-17-0

- Angela Lisnic, "Locul principatelor dunărene în acțiunile politico-militare ale marilor puteri în războiul Austro-Ruso-Turc din 1735–1739", in Revista de Istorie a Moldovei, Issue 1 (73), 2008, pp. 113–129.

- Radu Nedici, Formarea identității confesionale greco-catolice în Transilvania veacului al XVIII-lea: biserică și comunitate. Bucharest: Editura Universității București, 2013. ISBN 978-606-16-0279-7

- Șerban Papacostea, Oltenia sub stăpânirea austriacă (1718–1739). Bucharest: Editura enciclopedică, 1998. ISBN 973-45-0237-9

- Andrei Pogăciaș, Războiul ruso-austro-turc din 1736–39, in Constantin Bărbulescu, Ioana Bonda, Cecilia Cârja, Ion Cârja, Ana Victoria Sima (eds.), Identitate și alteritate: Studii de istorie politică și cultură, Vol. V, pp. 339–348. Cluj-Napoca: Presa Universitară Clujeană, 2011. ISBN 978-973-595-326-3

- Pompei Gh. Samarian, Medicina și Farmacia în Trecutul Românesc 1382–1775. Călărași: Tipografia Moderna, [n. y.]

- Corneliu Tamaș, "Marele spătar Radu Golescu și curentul antifanariot", in Buridava. Studii și Materiale, Issue 2/1976, pp. 67–71.

- Veronica Tamaș, "Administrația Olteniei în timpul ocupației austriece (1718–1739)", in Buridava, Vol. IV, 1982, pp. 119–125.

- Răzvan Theodorescu, "Episcopi și ctitori in Vâlcea secolului al XVIII-lea", in Buridava, Issue 7/2009, pp. 140–152.

- Al. Vianu, "Din acțiunea diplomatică a Țării Romînești în Rusia în anii 1736—1738", in Romanoslavica, Vol. VIII, 1963, pp. 19–26.

- States and territories established in 1718

- States and territories disestablished in 1739

- Subdivisions of the Habsburg monarchy

- History of Oltenia

- History of Wallachia (1714–1821)

- 18th century in Romania

- 1718 establishments in the Habsburg monarchy

- 1739 disestablishments in the Habsburg monarchy

- Austro-Turkish War (1716–1718)

- Russo-Turkish War (1735–1739)

- Germanization

- German communities in Romania

- Banat Bulgarian people