Boron compounds

Boron compounds are compounds containing the element boron. In the most familiar compounds, boron has the formal oxidation state +3. These include oxides, sulfides, nitrides, and halides.[1]

Halides

[edit]The trihalides adopt a planar trigonal structure. These compounds are Lewis acids in that they readily form adducts with electron-pair donors, which are called Lewis bases. For example, fluoride (F−) and boron trifluoride (BF3) combined to give the tetrafluoroborate anion, BF4−. Boron trifluoride is used in the petrochemical industry as a catalyst. The halides react with water to form boric acid.[1]

Oxygen compounds

[edit]Boron is found in nature on Earth almost entirely as various oxides of B(III), often associated with other elements. More than one hundred borate minerals contain boron in oxidation state +3. These minerals resemble silicates in some respect, although boron is often found not only in a tetrahedral coordination with oxygen, but also in a trigonal planar configuration. Unlike silicates, boron minerals never contain boron with coordination number greater than four. A typical motif is exemplified by the tetraborate anions of the common mineral borax, shown at left. The formal negative charge of the tetrahedral borate center is balanced by metal cations in the minerals, such as the sodium (Na+) in borax.[1] The tourmaline group of borate-silicates is also a very important boron-bearing mineral group, and a number of borosilicates are also known to exist naturally.[2]

Boranes

[edit]

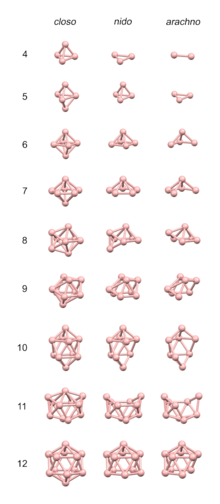

Boranes are chemical compounds of boron and hydrogen, with the generic formula of BxHy. These compounds do not occur in nature. Many of the boranes readily oxidise on contact with air, some violently. The parent member BH3 is called borane, but it is known only in the gaseous state, and dimerises to form diborane, B2H6. The larger boranes all consist of boron clusters that are polyhedral, some of which exist as isomers. For example, isomers of B20H26 are based on the fusion of two 10-atom clusters.

The most important boranes are diborane B2H6 and two of its pyrolysis products, pentaborane B5H9 and decaborane B10H14. A large number of anionic boron hydrides are known, e.g. [B12H12]2−.

The formal oxidation number in boranes is positive, and is based on the assumption that hydrogen is counted as −1 as in active metal hydrides. The mean oxidation number for the boron atoms is then simply the ratio of hydrogen to boron in the molecule. For example, in diborane B2H6, the boron oxidation state is +3, but in decaborane B10H14, it is 7/5 or +1.4. In these compounds the oxidation state of boron is often not a whole number.

Nitrides

[edit]The boron nitrides are notable for the variety of structures that they adopt. They exhibit structures analogous to various allotropes of carbon, including graphite, diamond, and nanotubes. In the diamond-like structure, called cubic boron nitride (tradename Borazon), boron atoms exist in the tetrahedral structure of carbon atoms in diamond, but one in every four B-N bonds can be viewed as a coordinate covalent bond, wherein two electrons are donated by the nitrogen atom which acts as the Lewis base to a bond to the Lewis acidic boron(III) centre. Cubic boron nitride, among other applications, is used as an abrasive, as it has a hardness comparable with diamond (the two substances are able to produce scratches on each other). In the BN compound analogue of graphite, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), the positively charged boron and negatively charged nitrogen atoms in each plane lie adjacent to the oppositely charged atom in the next plane. Consequently, graphite and h-BN have very different properties, although both are lubricants, as these planes slip past each other easily. However, h-BN is a relatively poor electrical and thermal conductor in the planar directions.[4][5]

Organoboron chemistry

[edit]A large number of organoboron compounds are known and many are useful in organic synthesis. Many are produced from hydroboration, which employs diborane, B2H6, a simple borane chemical. Organoboron(III) compounds are usually tetrahedral or trigonal planar, for example, tetraphenylborate, [B(C6H5)4]− vs. triphenylborane, B(C6H5)3. However, multiple boron atoms reacting with each other have a tendency to form novel dodecahedral (12-sided) and icosahedral (20-sided) structures composed completely of boron atoms, or with varying numbers of carbon heteroatoms.

Organoboron chemicals have been employed in uses as diverse as boron carbide (see below), a complex very hard ceramic composed of boron-carbon cluster anions and cations, to carboranes, carbon-boron cluster chemistry compounds that can be halogenated to form reactive structures including carborane acid, a superacid. As one example, carboranes form useful molecular moieties that add considerable amounts of boron to other biochemicals in order to synthesize boron-containing compounds for boron neutron capture therapy for cancer.

Compounds of B(I) and B(II)

[edit]As anticipated by its hydride clusters, boron forms a variety of stable compounds with formal oxidation state less than three. B2F4 and B4Cl4 are well characterized.[6]

Binary metal-boron compounds, the metal borides, contain boron in negative oxidation states. Illustrative is magnesium diboride (MgB2). Each boron atom has a formal −1 charge and magnesium is assigned a formal charge of +2. In this material, the boron centers are trigonal planar with an extra double bond for each boron, forming sheets akin to the carbon in graphite. However, unlike hexagonal boron nitride, which lacks electrons in the plane of the covalent atoms, the delocalized electrons in magnesium diboride allow it to conduct electricity similar to isoelectronic graphite. In 2001, this material was found to be a high-temperature superconductor.[7][8] It is a superconductor under active development. A project at CERN to make MgB2 cables has resulted in superconducting test cables able to carry 20,000 amperes for extremely high current distribution applications, such as the contemplated high luminosity version of the large hadron collider.[9]

Certain other metal borides find specialized applications as hard materials for cutting tools.[10] Often the boron in borides has fractional oxidation states, such as −1/3 in calcium hexaboride (CaB6).

From the structural perspective, the most distinctive chemical compounds of boron are the hydrides. Included in this series are the cluster compounds dodecaborate (B

12H2−

12), decaborane (B10H14), and the carboranes such as C2B10H12. Characteristically such compounds contain boron with coordination numbers greater than four.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (1985). "Bor". Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (in German) (91–100 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 814–864. ISBN 978-3-11-007511-3.

- ^ "Mindat.org - Mines, Minerals and More". mindat.org. Archived from the original on 22 April 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ Welch, Alan J. (2013). "The significance and impact of Wade's rules". Chem. Commun. 49 (35): 3615–3616. doi:10.1039/C3CC00069A. PMID 23535980.

- ^ Engler, M. (2007). "Hexagonal Boron Nitride (hBN) – Applications from Metallurgy to Cosmetics" (PDF). Cfi/Ber. DKG. 84: D25. ISSN 0173-9913. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ Greim, Jochen & Schwetz, Karl A. (2005). "Boron Carbide, Boron Nitride, and Metal Borides". Boron Carbide, Boron Nitride, and Metal Borides, in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH: Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a04_295.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Jones, Morton E. & Marsh, Richard E. (1954). "The Preparation and Structure of Magnesium Boride, MgB2". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 76 (5): 1434–1436. doi:10.1021/ja01634a089.

- ^ Canfield, Paul C.; Crabtree, George W. (2003). "Magnesium Diboride: Better Late than Never" (PDF). Physics Today. 56 (3): 34–40. Bibcode:2003PhT....56c..34C. doi:10.1063/1.1570770. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ "Category "News+Articles" not found - CERN Document Server". cds.cern.ch. Archived from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Cardarelli, François (2008). "Titanium Diboride". Materials handbook: A concise desktop reference. pp. 638–639. ISBN 978-1-84628-668-1. Archived from the original on 8 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2016.