List of high commissioners of Australia to the United Kingdom

| High Commissioner of Australia to the United Kingdom | |

|---|---|

| |

since 26 January 2023 | |

| Style | His/Her Excellency |

| Reports to | Minister for Foreign Affairs |

| Residence | Stoke Lodge, Hyde Park Gate |

| Seat | High Commission of Australia, London |

| Nominator | Prime Minister of Australia |

| Appointer | Governor-General of Australia |

| Inaugural holder | Sir George Reid |

| Formation | 22 January 1910 |

| Website | Australian High Commission, United Kingdom |

The high commissioner of Australia to the United Kingdom is an officer of the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the head of the High Commission of the Commonwealth of Australia to United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in London. The position has the rank and status of an ambassador extraordinary and plenipotentiary. The high commissioner also serves as Australia's permanent representative to the International Maritime Organization (since 1959),[1] a trustee of the Imperial War Museum and Australia's Commonwealth War Graves Commissioner.

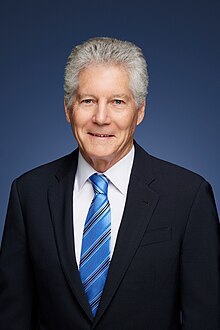

On 30 September 2022, the former defence and foreign affairs minister, Stephen Smith, was named as the next high commissioner, and took up office on 26 January 2023.[2][3][4]

Posting history

[edit]From Federation in 1901, the new Commonwealth government arranged to have all federal matters and communications handled by the various Agents-General of the states in London (acting with shared responsibility). Prior to federation, each of the Australian colonies were represented through the Agents-General, the oldest being South Australia from 1856. From 1905 the Agents-General formed a committee to jointly deal with Australian matters but on 20 February 1906, the Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin, announced the establishment of a dedicated Australian office in London, with the Secretary of the Department of Defence, Muirhead Collins, as the new office head.[5] The States of New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Victoria and Western Australia continue to be represented by agents-general. Since the revival of the NSW agent-general in 2021, Tasmania is the only state that does not have an agent-general in London, having abolished its post in 1981 as a cost-saving measure.[6][7]

The High Commission of Australia in London is Australia's oldest diplomatic posting, and was created through the passage of the High Commissioner Act 1909 on 13 December 1909, which established the role as appointed by the Governor-General and defined that they would "act as representative and resident agent of the Commonwealth in the United Kingdom, and in that capacity exercise such powers and perform such duties as are conferred upon and assigned to him by the Governor-General [and] carry out such instructions as he receives from the Minister respecting the commercial, financial, and general interests of the Commonwealth and the States in the United Kingdom and elsewhere."[8] After the appointment of Reid as High Commissioner, Collins continued to serve as Official Secretary to the High Commissioner until his retirement in 1917. On 24 July 1913, King George V laid the foundation stone of Australia House, the future site of the Australia mission, which he also officially opened five years later on 3 August 1918.[5]

The High Commissioner Act was amended several times (1937, 1940, 1945, 1952, 1957, 1966) and was repealed by the High Commission (United Kingdom) Act Repeal Act 1973, when Foreign Minister Don Willesee placed the High Commission under the terms of the Public Service Act like all other diplomatic posts.[9] The new act altered the status of the High Commission to one of equality with all other bilateral posts, in recognition of the fact that Australia's relationship with the United Kingdom had changed.[5] Four of Australia's early prime ministers served terms as High Commissioner after leaving office: Reid, Fisher, Cook and Bruce. The position has also been filled by five people who have served as the leader of the opposition in the Australian parliament: Reid, Fisher, Cook, H.V. Evatt and Alexander Downer. Until 1973, every high commissioner was a former government minister. Since then, a number of senior career diplomats have held the post, although former politicians are still regularly appointed.

From 1975 to 2001, the work of the High Commission was assisted by the Australian Consulate in Manchester. Established on 1 August 1975, the consulate largely dealt with trade and migration matters.[10][11]

Residence

[edit]Prior to 1950, the high commissioner lived in various rented premises. From 1910, the first high commissioner, Sir George Reid, rented the residence of John Henniker Heaton at 33 Eaton Square, Belgravia.[12][13] In 1927, the government of Prime Minister Stanley Bruce acquired the lease of 18 Ennismore Gardens in Knightsbridge, from the Earl of Listowel (and succeeding Lord Castlemaine as lessee), a four-storey 1858 terrace house, as the residence for high commissioner Sir Granville Ryrie.[14][15][16] This remained the official residence until 1940, when high commissioner Stanley Bruce downsized to a smaller flat during the war years, and it remained empty until 1946, when high commissioner Jack Beasley took up residence.[17][18] However, the Beasleys did not favour the size, style, and expense of this residence, and in late 1946 they moved to a smaller terraced house in Ilchester Place, Holland Park, which remained the official residence until 1950.[19][20][21][22]

However, a need for a standalone official residence was identified by the Department of External Affairs, and a two-storey, 20-room, circa 1838 Georgian style residence known as "Stoke Lodge" at 45 Hyde Park Gate in Kensington was acquired in December 1950, with Resident Minister Eric Harrison, and his wife, being the first occupants.[23][24][25][26] Since 1950, Stoke Lodge has been the official residence of all subsequent high commissioners, and often serves as an official reception venue. On 29 January 1952, high commissioner Sir Thomas White hosted Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh prior to their departure on a tour of Kenya, where Elizabeth would become Queen on 6 February.[27][28] Stoke Lodge was originally built in 1838 by Robert Thew, a major of artillery in the East India Company, and in 1851 was the residence of Italian opera singer, Giulia Grisi.[29] Caroline Ashurst Stansfeld was also resident when she died in 1885.[30]

High commissioners

[edit]| # | Officeholder | Image | Term start date | Term end date | Time in office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sir George Reid |

|

22 January 1910 | 10 January 1916 | 5 years, 353 days | [31][32][33] |

| 2 | Andrew Fisher |

|

22 January 1916 | 21 April 1921 | 5 years, 89 days | [34] |

| – | Malcolm Shepherd (Acting) |

|

21 April 1921 | 11 November 1921 | 204 days | [35] |

| 3 | Sir Joseph Cook |

|

11 November 1921 | 10 May 1927 | 5 years, 180 days | [36] |

| 4 | Sir Granville Ryrie |

|

11 May 1927 | 30 July 1932 | 5 years, 80 days | [37][38][39] |

| – | J. R. Collins (Acting) |

30 July 1932 | 7 September 1932 | 39 days | [40] | |

| 5 | Stanley Bruce (Resident Minister until 6 October 1933) |

|

7 September 1932 | 5 October 1945 | 13 years, 28 days | [41][42][43][44][45] |

| – | H. V. Evatt (Resident Minister) |

|

5 October 1945 | 17 October 1945 | 12 days | [46][47] |

| – | John Shiels Duncan (Acting) |

17 October 1945 | 24 January 1946 | 99 days | [48][49] | |

| 6 | Jack Beasley (Resident Minister until 14 August 1946) |

|

24 January 1946 | 2 September 1949 | 3 years, 221 days | [50][51][52][53][54] |

| – | Sir Norman Mighell (Acting) |

|

2 September 1949 | 23 April 1950 | 233 days | [55][56] |

| 7 | Eric Harrison (Resident Minister) |

|

23 April 1950 | 30 March 1951 | 341 days | [57][58][59][60][61][62] |

| – | Edwin McCarthy (Acting) |

|

30 March 1951 | 21 June 1951 | 83 days | [63][64] |

| 8 | Sir Thomas White |

|

21 June 1951 | 20 June 1956 | 4 years, 365 days | [65][66] |

| – | Sir Edwin McCarthy (Acting) |

|

20 June 1956 | 25 October 1956 | 127 days | [67] |

| – | Sir Eric Harrison |

|

25 October 1956 | 25 October 1964 | 8 years, 0 days | [68][69][70][71] |

| 9 | Sir Alexander Downer |

|

25 October 1964 | 24 October 1972 | 7 years, 365 days | [72][73][74][75][76] |

| – | Bill Pritchett (Acting) |

24 October 1972 | 28 January 1973 | 96 days | [77] | |

| 10 | John Armstrong |

|

28 January 1973 | 31 January 1975 | 2 years, 3 days | [78][79][80][81][82] |

| 11 | Sir John Bunting |

|

1 February 1975 | March 1977 | 2 years, 1 month | [82][83][84][85] |

| 12 | Sir Gordon Freeth |

|

March 1977 | March 1980 | 3 years | [86][87][88] |

| 13 | Sir James Plimsoll |

|

March 1980 | 25 March 1981 | 1 year | [89][90][91] |

| – | Frank Murray (Acting) |

25 March 1981 | April 1981 | 0 months | [92] | |

| 14 | Sir Victor Garland |

|

April 1981 | 21 December 1983 | 2 years, 8 months | [93][94][95] |

| 15 | Alfred Parsons | 22 December 1983 | March 1987 | 3 years, 2 months | [96][97] | |

| 16 | Doug McClelland |

|

21 March 1987 | March 1991 | 3 years, 11 months | [98][99][100] |

| 17 | Richard Smith | March 1991 | April 1994 | 3 years, 1 month | [101] | |

| 18 | Neal Blewett |

|

April 1994 | 20 March 1998 | 3 years, 11 months | [102] |

| 19 | Philip Flood |

|

20 March 1998 | August 2000 | 2 years, 4 months | [103] |

| 20 | Michael L'Estrange |

|

August 2000 | February 2005 | 4 years, 6 months | [104] |

| 21 | Richard Alston |

|

February 2005 | September 2008 | 3 years, 7 months | [105] |

| 22 | John Dauth |

|

September 2008 | 23 August 2012 | 3 years, 11 months | [106] |

| 23 | Mike Rann |

|

23 August 2012 | 31 March 2014 | 1 year, 220 days | [107] |

| 24 | Alexander Downer |

|

31 March 2014 | 27 April 2018 | 4 years, 27 days | [108][109] |

| 25 | George Brandis |

|

3 May 2018 | 30 April 2022 | 3 years, 362 days | [110][111] |

| – | Lynette Wood (Acting) |

|

30 April 2022 | 26 January 2023 | 2 years, 206 days | [112] |

| 26 | Stephen Smith |

|

26 January 2023 | Incumbent | 1 year, 301 days | [2][3][4] |

See also

[edit]- List of high commissioners of the United Kingdom to Australia

- Australia–United Kingdom relations

- Agent-General for New South Wales

References

[edit]- ^ "International Maritime Organization (IMO)". Australia Maritime Safety Authority. Australian Government. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ a b Wong, Penny (30 September 2022). "Appointment of Australian Ambassadors, High Commissioners and Consuls-General" (Press release). Minister for Foreign Affairs, Australian Government. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ a b Hurst, Daniel (30 September 2022). "Stephen Smith named UK high commissioner as government flags fewer political appointments". The Guardian Australia. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ a b Smith, Stephen (27 January 2023). "Presented as the Australian High Commissioner to the U.K". Twitter. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ a b c "CA 241: Australian High Commission, United Kingdom [London]". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ Turnbull, Greg (14 July 1981). "$20m in rent helps diplomats keep up with the Joneses". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 8.

- ^ Bennison, Peter (2006). "Agents-General for Tasmania". The Companion to Tasmanian History. Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies, University of Tasmania. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "High Commissioner Act 1909 (No. 22)". Federal Register of Legislation. Australian Government. 13 December 1909. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ "High Commissioner (United Kingdom) Act Repeal Act 1973". Federal Register of Legislation. Australian Government. 29 November 1973. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ "CA 7354: Australian Consulate, Manchester [United Kingdom]". NAA. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ "The wizards of Oz". Manchester Evening News. 10 August 2004. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ "Sir George Reid". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 8 June 1910. p. 9. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Sir George Reid". Evening News. New South Wales, Australia. 7 June 1910. p. 6. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "High Commissioner". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 23 September 1927. p. 3. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "High Commissioner". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 25 October 1927. p. 10. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Near the Palace". The Daily Telegraph. New South Wales, Australia. 23 September 1927. p. 2. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "London Residence of High Commissioner Australia Returns to No. 18". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 29 January 1946. p. 6 (Magazine). Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Mr Beasley In London". The Telegraph. Queensland, Australia. 1 February 1946. p. 5. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Mr. Beasley to Quit 24-Roomed Residence". News. South Australia. 22 October 1946. p. 1. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "More Modest Home For The Beasleys". The Newcastle Sun. New South Wales, Australia. 25 October 1946. p. 12. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Mr. Beasley Moving to New Home". Newcastle Morning Herald And Miners' Advocate. New South Wales, Australia. 24 October 1946. p. 1. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Mrs. Beasley In New Home". The Courier-mail. Queensland, Australia. 17 January 1947. p. 8. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "New Residence For Minister". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 14 December 1950. p. 4. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Australia's 'Home' in London". The Age. Victoria, Australia. 22 September 1951. p. 5. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "New Australian Official Home In London". The Advertiser (Adelaide). South Australia. 15 December 1950. p. 4. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Australian Minister's New London Home". The Advertiser (Adelaide). South Australia. 15 December 1950. p. 4. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Australians give party for Royal party". The Australian Women's Weekly. Australia, Australia. 6 February 1952. p. 15. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Aust. menu for Elizabeth". The Daily Telegraph. New South Wales, Australia. 25 January 1952. p. 4. Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Sheppard, F. H. W., ed. (1975). "Chapter III - Hyde Park Gate, Kensington Gate and Palace Gate". Survey of London: Volume 38, South Kensington Museums Area. London: London County Council. pp. 26–38. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ Kathryn Gleadle (2004). "Caroline Ashurst Stansfeld". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ "Appointment of High Commissioner of the Commonwealth". Commonwealth of Australia Gazette. No. 5. Australia. 22 January 1910. p. 48. Retrieved 10 March 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "High Commissioner". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 16 December 1909. p. 6. Retrieved 15 February 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The High Commissioner". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 28 February 1910. p. 7. Retrieved 15 February 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "High Commissioner". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 28 October 1915. p. 6. Retrieved 15 February 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The Secretary". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 8 January 1921. p. 12. Retrieved 15 February 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "High Commissioner". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 12 November 1921. p. 13. Retrieved 15 February 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "High Commissioner for Australia". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 23 March 1927. p. 16. Retrieved 15 February 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Government Gazette Proclamations and Legislation". Commonwealth of Australia Gazette. No. 45. Australia, Australia. 5 May 1927. p. 871. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "High Commissioner". The Telegraph. Queensland, Australia. 8 March 1932. p. 5. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Sir Granville Ryrie to Leave London This Week". News. South Australia. 27 July 1932. p. 6. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Mr. S. M. Bruce". The West Australian. Western Australia. 8 September 1932. p. 13. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Government Gazette Appointments and Employment". Commonwealth of Australia Gazette. No. 56. Australia, Australia. 12 October 1933. p. 1401. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "High Commissioner Act 1909-1937". Commonwealth of Australia Gazette. No. 53. Australia, Australia. 8 September 1938. p. 2196. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "High Commissioner Act 1909-1940". Commonwealth of Australia Gazette. No. 222. Australia, Australia. 14 October 1943. p. 2287. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "High Commissioner Act 1909-1940". Commonwealth of Australia Gazette. No. 184. Australia, Australia. 14 September 1944. p. 2142. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Evatt-Beasley Missions Abroad". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 29 August 1945. p. 5. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Dr. Evatt Leaves for London". The Australian Worker. New South Wales, Australia. 5 September 1945. p. 1. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Dr. Evatt Going To Washington". News. South Australia. 12 October 1945. p. 4. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "High Commissioner". The West Australian. Western Australia. 18 October 1945. p. 6. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Evatt and Beasley for London". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 29 August 1945. p. 1. Retrieved 10 March 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Arsenal for the Empire". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 25 January 1946. p. 3. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "London Residence of High Commissioner Australia Returns to No. 18". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 29 January 1946. p. 6 (The Sydney Morning Herald Magazine). Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Mr. Beasley's Mission". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 21 December 1945. p. 2. Retrieved 10 March 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Mr. Beasley High Commissioner". The Border Watch. South Australia. 3 August 1946. p. 1. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Mr. Mighell to Retire". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 19 October 1949. p. 5. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Retirement of Normal Rupert Mighell As Deputy High Commissioner". Commonwealth of Australia Gazette. No. 49. Australia, Australia. 24 August 1950. p. 2120. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Resided Minister in London". Kalgoorlie Miner. Western Australia. 27 April 1950. p. 5. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Harrison Resident Minister in UK". The Sun. New South Wales, Australia. 16 February 1950. p. 1. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Harrison Gets Post in London". News. South Australia. 16 February 1950. p. 1. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Resident Minister in London". Kalgoorlie Miner. Western Australia. 25 April 1950. p. 5. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Georgian Home for Mr. Harrison". Illawarra Daily Mercury. New South Wales, Australia. 14 December 1950. p. 2. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Harrison On Way Home". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 31 March 1951. p. 2. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Offices Abolished, Created, Etc". Commonwealth of Australia Gazette. No. 23. Australia, Australia. 27 April 1950. p. 984. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Appointments by Cabinet". Cairns Post. Queensland, Australia. 1 April 1950. p. 5. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Appointment of High Commissioned in the United Kingdom". Commonwealth of Australia Gazette. No. 47. Australia, Australia. 5 July 1951. p. 1684. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "May Re-enter Politics". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 19 June 1956. p. 1. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Tale Over in August Harrison Appointed to London Post". The Central Queensland Herald. Queensland, Australia. 24 May 1956. p. 9. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Appointment of High Commissioner of the Commonwealth of Australia in the United Kingdom". Commonwealth of Australia Gazette. No. 63. Australia, Australia. 1 November 1956. p. 3295. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Sir Eric Harrison For London Post". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 24 May 1956. p. 1. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "P.M. lauds Sir Eric Harrison". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 26 October 1964. p. 9. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Audience with the Queen". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 23 October 1964. p. 2. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Re-appointment of Sir Alexander Downer". Current Notes on International Affairs. 40 (11): 651. 30 November 1969. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Further term in UK post". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 3 June 1970. p. 1. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Re-appointment of Sir Alexander Downer". Current Notes on International Affairs. 42 (10): 564. 31 October 1971. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Downer reappointed". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 29 September 1971. p. 1. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Change in top London post". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 21 October 1972. p. 1. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Australian High Commissioner - London". Current Notes on International Affairs. 43 (10): 533. October 1972. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Australia's New High Commissioner In London". Current Notes on International Affairs. 43 (12): 594. December 1972. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Labor stalwart to London post". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 13 December 1972. p. 1. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Diplomat sees his job as 'mending fences'". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 14 December 1972. p. 3. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "High Commissioner a 'character'". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 18 December 1974. p. 18. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b Whitlam, Gough (23 August 1974). "Appointment approved by the Executive Council" (Press release). ParlInfo: Australian Government. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ "New Australian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom". Australian Foreign Affairs Record. 45 (9): 575. September 1974. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Bunting appointed to UK job". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 24 August 1974. p. 1. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Diplomat". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 26 February 1975. p. 17. Retrieved 1 July 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Freeth to be new UK envoy". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 21 February 1977. p. 1. Retrieved 30 June 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "PM defends Freeth as UK envoy". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 23 February 1977. p. 11. Retrieved 30 June 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Attitude a cause of UK's decline: Freeth". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 13 March 1980. p. 14. Retrieved 30 June 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Peacock, Andrew (4 February 1980). "Appointment of Australian High Commissioner to Britain" (Press release). Australian Government.

- ^ "Sir James Plimsoll named as envoy to Britain". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 5 February 1980. p. 1. Retrieved 30 June 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Plimsoll leaves London". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 26 March 1981. p. 7. Retrieved 30 June 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "In Brief: London changes". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 26 March 1981. p. 3. Retrieved 30 June 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Ministers Go in Cabinet Shake". Papua New Guinea Post-courier. International, Australia. 3 November 1980. p. 7. Retrieved 30 June 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "High commissioner Garland may lose his job in London". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 8 March 1983. p. 1. Retrieved 30 June 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "British-Australian relations very good, Garland says". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 22 December 1983. p. 8. Retrieved 30 June 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Appointed to Britain". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 19 October 1983. p. 3. Retrieved 30 June 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "High Commissioner to UK". Australian Foreign Affairs Record. 54 (10): 630. October 1983. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ "McClelland's London job official". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 24 January 1987. p. 7. Retrieved 30 June 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "In Brief: McClelland arrives". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 23 March 1987. p. 8. Retrieved 30 June 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "High Commissioner to London". Australian Foreign Affairs Record. 58 (1): 29–30. 31 January 1987. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Evans, Gareth (29 December 1990). "Diplomatic appointment - United Kingdom" (Press release). Australian Government.

- ^ Evans, Gareth (13 March 1994). "Diplomatic appointment: United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland" (Press release). Australian Government.

- ^ Downer, Alexander (20 March 1998). "Diplomatic Appointment - High Commissioner to the United Kingdom" (Press release). Australian Government. Archived from the original on 12 February 2014.

- ^ Howard, John (2 February 2000). "Diplomatic Appointment: High Commissioner to the United Kingdom". Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (Press release). Commonwealth of Australia. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ^ Downer, Alexander (17 December 2004). "Diplomatic Appointment - High Commissioner to the United Kingdom" (Press release). Australian Government. Archived from the original on 12 February 2014.

- ^ Smith, Stephen (6 August 2008). "Diplomatic Appointment - High Commissioner to United Kingdom". Australian Government. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008.

- ^ Carr, Bob (23 August 2012). "High Commissioner to the United Kingdom" (Press release). Australian Government.

- ^ Bishop, Julie (31 March 2014). "High Commissioner to the United Kingdom" (Press release). Australian Government.

- ^ Kenny, Mark (18 February 2014). "Labor's man an also-ran as Downer heads for London". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Bishop, Julie (20 March 2018). "High Commissioner to the United Kingdom" (Press release). Australian Government.

- ^ Starick, Paul (16 April 2018). "Achilles injury to George Brandis". Adelaide Advertiser. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ Osborne, Paul (5 May 2022). "Australia sends senior diplomat to London". 7 News. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Bridge, Carl; Bongiorno, Frank; Lee, David, eds. (2010). The High Commissioners: Australia's Representatives in the United Kingdom, 1910–2010 (PDF). Canberra: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. ISBN 9781921612114. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2019.