British Army in Australia

|

| British Army of the British Armed Forces |

|---|

| Components |

| Administration |

| Overseas |

| Personnel |

| Equipment |

| History |

| Location |

| United Kingdom portal |

From the late 1700s until the end of the 19th century, the British Empire established, expanded and maintained a number of colonies on the continent of Australia. These colonies included New South Wales, Van Diemen's Land, Western Australia, South Australia, Victoria and Queensland. Many of these were initially formed as penal settlements, and all were built on land occupied by Indigenous Australians. In order to keep the large number of transported convicts under control, enforce colonial law and fight the Australian frontier wars, British military elements, including the British Army, were deployed and garrisoned in Australia. From 1790 to 1870 over 30 different regiments of the British Army consisting of a combined total of around 20,000 soldiers were based in the Australian British colonies.[1]

The New South Wales Corps (1790–1810)

[edit]

The first British colonial settlement in Australia of Sydney was established in 1788 with the protection of four companies of the Corps of Royal Marines. In 1790 these were mostly replaced with soldiers of the New South Wales Corps, a regiment raised specifically for service in Australia. This regiment was based in Australia until 1810. During this time they were deployed to fight in the Australian frontier wars, suppress convict uprisings and be garrisoned in further remote places such as Norfolk Island and Van Diemen's Land. The officers of this corps, such as Francis Grose and John Macarthur, are remembered mostly for their corruption and overthrowing Governor William Bligh during the Rum Rebellion of 1808. The New South Wales Corps is also known as the Rum Corps for their monopolisation on the trade of rum which was the common currency of much of the time of their deployment.[2]

In 1795, European settlers were in open conflict with the Aboriginal inhabitants they were displacing along the Deerubbin (Hawkesbury) River. Lieutenant Governor William Paterson of the New South Wales Corps ordered 62 soldiers into the area "to destroy as many as they could of the wood tribe and...to erect gibbets...whereupon the bodies of all they might kill were to be hung." Several punitive expeditions were conducted resulting in the deaths of over a dozen Darug people. Two years later, soldiers based at Parramatta were involved in a skirmish with a group of Bidjigal warriors led by Pemulwuy. The soldiers captured Pemulwuy and killed five of his associates during this Battle of Parramatta. Further conflict in the Hawkesbury region in 1805 resulted in Governor Philip Gidley King deploying detachments of soldiers to protect the settlers against "uncivilised insurgents". Again a number of armed patrols were organised which ended in more Aboriginal deaths and the capture of the Indigenous resistance leader Musquito.[3]

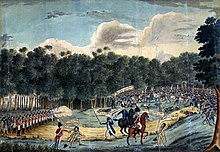

In March 1804, over 200 mostly Irish convicts stationed on a prison farm at Castle Hill near Sydney rebelled and organised themselves into a makeshift armed force. Major George Johnston of the New South Wales Corps led a detachment of soldiers and loyalist civilians which quickly defeated the rebellion at the Battle of Vinegar Hill. Over 15 convicts were killed, nine were later hanged or gibbeted.[4] Later that month, ten soldiers of the New South Wales Corps with thirty prisoners from the rebellion and a number of skilled workers were sent by Governor Philip Gidley King to establish a convict colony at the mouth of the Hunter River. This settlement came to be known as Newcastle.[5]

1810s

[edit]Soldiers of the 46th and 48th Regiments were involved in the capture of bushrangers such as Michael Howe in Van Dieman's Land during this period.[citation needed]

The ongoing Hawkesbury and Nepean Wars between encroaching settlers and the resident Darug and Gandangara people flared. In March 1816, a punitive expedition of by a group of settlers was surprised and ambushed at Silverdale by a group of Aboriginal people armed with muskets and spears, and four settlers were killed. Governor Lachlan Macquarie ordered an armed reprisal "to inflict exemplary and severe punishment on the mountain tribes...to strike them with terror...clearing the country of them entirely." Macquarie sent three detachments of the 46th Regiment of Foot into the region with Captain James Wallis being placed in command of the detachment of grenadiers.[6]

Wallis' detachment of the 46th Regiment scoured the area around Appin and Minto and were soon informed that a group of Aborigines were camping near the Cataract River. In the early morning of 17 April, Wallis led a surprise attack on this camp with "smart firing" resulting in the deaths of at least fourteen Aboriginal people from both gunshot wounds or from falling off the rocky cliffs around the river while fleeing. Most of the dead were old men, women and children. Wanted men, Cannabaygal and Dunnell were also killed and their corpses hung from trees near Appin to "strike the survivors with greater terror." Cannabaygal's skull was later collected and sent to the University of Edinburgh where it featured in a book on phrenology by Sir George Mackenzie.[6][7]

Governor Macquarie praised Wallis for acting "perfectly in conformity to the instructions I had furnished." Wallis was rewarded with fifteen gallons of rum and was appointed as commandant and magistrate of the penal colony at Newcastle. This incident became known as the Appin Massacre.[6]

1820s

[edit]In March 1821, Captain Francis Allman of the 48th Regiment led a party of forty soldiers and sixty prisoners to form a convict settlement at the mouth of the Hastings River. The settlement was named Port Macquarie.[8] Later that year, during a patrol to locate runaway convicts, ten Irish soldiers in a detachment of the 48th mutinied. A skirmish, dubbed the Battle of Croppy's Hill, ensued which resulted in the suppression of the mutiny and the death of one of the rebels.[9] Soldiers were also involved in the shootings of Aboriginal people along the Wilson River to the west of Port Macquarie during the establishment of agricultural outposts.[10] Multiple soldier fatalities committed by local Aboriginal people[11] and convicts[12] occurred during the nine year period of Port Macquarie being a prison colony.

In September 1824, fourteen soldiers of the 40th Regiment led by Lieutenant Henry Miller established the Moreton Bay penal colony. Initially located on the Redcliffe Peninsula, the settlement had to be moved in May 1825 to the north bank of the Brisbane River due to crop failure and conflict with the local Aboriginal people. This new site for the convict prison was called Edenglassie, but soon became known as Brisbane.[13]

During a period of martial law in 1824, re-inforcements from the 40th were used against the Wiradjuri people in the Bathurst region of New South Wales. This deployment rapidly concluded the Bathurst War.[14] The British Army lacked a mounted division in the Australian colonies and in 1825, after a conflict with the Wiradjuri people, it was deemed necessary to form one. The New South Wales Mounted Police was thereby created which consisted of soldiers from various army regiments who volunteered to join the force. This mounted infantry was eventually disbanded in 1850 when it became a civilian policing unit.[15]

In Tasmania, from 1824 until 1831, a violent guerilla conflict known as the "Black War" erupted between European settlers and Tasmanian Aboriginals; the conflict claimed the lives of 200 settlers and roughly 600 to 900 Tasmanian Aboriginals, nearly exterminating the latter. Soldiers from the 39th, 40th, 57th and 63rd regiments participated in the conflict, and adopted a strategy which consisted of three broad methods; pursuit parties, roving parties and the Black Line. Pursuit parties were small garrisons in various frontier localities who would pursue Aboriginal raiders when they attacked, while roving parties were search and destroy patrols. The Black Line was a 300 km long line of soldiers and armed settlers that attempted to sweep the remaining Aboriginal population out of the settled districts and corner them into the Tasman Peninsula. The Black Line strategy was employed toward the end of the war, and although it was poorly implemented, it was still able to eliminate the remaining Aboriginal resistance.[16]

In September 1824, a military detachment consisting of 27 Royal Marines and 34 soldiers of the 3rd Regiment of Foot established a military outpost on Melville Island in the far north of Australia. The outpost was named Fort Dundas and was the first attempt to colonise the tropical regions of the continent. The settlement was abandoned in 1828 due mostly to the persistent raids by the local Tiwi people. A second attempt to set up a colonial outpost in the area occurred in 1827 at a location on the nearby Cobourg Peninsula. Captain Henry Smyth led 30 soldiers of the 39th Regiment and 14 Royal Marines in the construction of this settlement which was given the name of Fort Wellington. Smyth enacted aggressive measures against the local Iwaidja people, which included the use of artillery and the proclamation of bounties. After a massacre of a group of Iwaidja on a beach close to the fort, Smyth was recalled and replaced by Captain Collet Barker who markedly improved relations with the Iwaidja. However, despite Barker's efforts, Fort Wellington was also abandoned in August 1829.[14]

In 1826, two privates of the 57th Regiment, Joseph Sudds and Patrick Thompson, concluded that the life of a soldier was worse than that of a prisoner and decided to rob a Sydney shop in order to become convicts. Their scheme incensed Ralph Darling, the then Governor of New South Wales, who ordered them to 7 years hard labour, strapped in irons, chains and spiked collars. Sudds soon died and the resultant controversy saw Governor Darling labelled a tyrant in the colonial press. Darling then instigated a widespread crack down on journalism, which included the jailing of a newspaper editor.[4]

1830s

[edit]During the early years of the Moreton Bay penal settlement, the 17th Regiment of Foot was involved in two documented massacres of Aboriginal Australians.[17] The first was on Moreton Island where, on 1 July 1831, Captain James Clunie with a detachment of soldiers attacked a camp of Ngugi people killing up to twenty of them. George Watkins recorded: "nearly all were shot down...a young boy...escaped with a few others by hiding in a clump of bushes"[18][17] The second occurred in December 1832 on the neighbouring island of Minjerribah. Six members of the local Nunukul tribe were killed at the hands of Captain Clunie and the 17th Regiment in a reprisal raid.[19][20][17]

In January 1834, soldiers of the 4th Regiment of Foot garrisoned at Norfolk Island and led by Captain Foster Fyans, were ordered to suppress a major convict uprising. In the conflict that followed, five convicts and a soldier were killed. The superintendent of the penal colony, Colonel James Morisset, allowed Fyans to torture and subject the surviving ringleaders to harsh punishment which earned him the name of "Flogger Fyans". Fourteen convicts were later sentenced to death and hanged.[4]

In October 1834, after several years of ongoing conflict between encroaching settlers and the Pinjarup people along the Murray River in south-western Western Australia, soldiers of the 21st Regiment of Foot were called upon to establish a military outpost in the region. Led by Governor James Sterling, the soldiers with members of mounted police, were soon involved in a skirmish with the Pinjarup that has become known as the Battle of Pinjarra. Probably around forty Pinjarup as well as Captain Theophilus Ellis of the mounted police were killed in this encounter.[14]

In the mid 1830s, the Gringai people who lived in the valleys and hills to the north of Newcastle, were at war with European settlers. In 1835, in response to the murder of four men and two shepherds[21] Richard Bourke, Governor of New South Wales, ordered 50 soldiers from the 17th Regiment to proceed to the scene of the disturbance.[22] This military operation was commanded by Major William Croker,[23] and his directive was to vigorously suppress the resistance. Croker's men returned after a month in the disputed area.[24]

1840s

[edit]In 1842 a detachment of the 96th Regiment was ordered to proceed to the Port Lincoln settlement where strong Aboriginal resistance had caused the widespread abandonment of land-holdings around that town. Despite having to retreat during a battle with the Battara people near Koppio, the soldiers gained the upper hand after conducting several punitive expeditions.[25]

The Governor of Western Australia, Charles Fitzgerald, led a mineral exploration surveying party to Champion Bay and the Murchison River in 1848. Augustus Charles Gregory accompanied the Governor and they were protected by soldiers of the 96th Regiment. Near the Bowes River, the party was surrounded by over 50 local Aboriginal people who threw spears and stones, with one grabbing a man by the arm and threatening to hit him with a dowak. The Governor, fearing the party would be cut off, shot dead one man and was subsequently speared in the leg. As the surveying party retreated, the soldiers gave regular fire and another two people were shot.[26] A lead mining venture was soon functioning in the region and a large detachment of 30 soldiers of the 99th Regiment under Lieutenant L.R. Elliot was garrisoned at Champion Bay to guard the operations.[27] In 1850, Lieutenant Elliot took 15 of these soldiers to construct a fort at Quoin Bluff in Shark Bay to protect guano mining activities there.[28]

In 1849, a detachment of the 11th Regiment of Foot based at Brisbane conducted a night-time dispersal of Aboriginal people camped at "York's Hollow". Led by Lieutenant George Cameron, the detachment split into two groups, surrounded the sleeping members of the camp and fired into it. Several Aboriginal people were wounded.[29][30]

1850s

[edit]

In December 1854, soldiers of the 12th and 40th Regiments led by Captain John Wellesley Thomas were involved in the suppression of gold-miners associated with the Eureka Rebellion near Ballarat in Victoria. Several soldiers were killed during the conflict at the Eureka Stockade including Captain Wise of the 40th. Around 34 fatalities of the miners occurred.[1][31]

1860 to 1870

[edit]In 1861, a series of anti-Chinese riots perpetrated by European gold miners at Lambing Flat in New South Wales resulted in the military being deployed to restore order. In February white miners "rolled up" and violently expelled Chinese miners from the goldfields. The local police force arrested 15 of the rioters but the presence of thousands more subsequently intimidated them into releasing the prisoners.[32] A request for military support was issued and a force of 130 soldiers of the 12th Regiment, supported by around 100 mounted police and artillery, was sent from Sydney under the command of Captain Atkinson.[33] The presence of the soldiers restored calm but after they left in early June, the disturbances rapidly re-ignited. On 30 June, thousands of European miners again attacked the Chinese quarters, with widespread assaulting and pillaging. Two weeks later, when the local police arrested several of the rioters, the miners attacked the police. In the skirmish several miners were killed and the police abandoned Lambing Flat fearing massive reprisals.[34] Assistance from the military was again requested and a force of 225 men was led by Colonel John Kempt was dispatched from Sydney. This force included 110 men of the 12th Regiment with support of dozens of marines and members of the Royal Artillery.[35] Once more, the presence of the soldiers alone kept the peace and this time further troubles were avoided.[36]

The 18th Regiment of Foot and the Royal Artillery were the final regiments of the British Army to be stationed in Australia. The last of these soldiers departed Circular Quay aboard the Silver Eagle on 28 August 1870. There was a considerable number of desertions in the week before the departure.[37]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Stanley, Peter (1986), The remote garrison : the British Army in Australia 1788-1870, Kangaroo Press, ISBN 978-0-86417-091-0

- ^ Evatt, H. V. (1971), Rum rebellion : a study of the overthrow of Governor Bligh by John MacArthur and the New South Wales Corps, Lloyd O'Neill, ISBN 978-0-85550-037-5

- ^ Turbet, Peter (2011), First frontier : the occupation of the Sydney region 1788-1816, Rosenberg Publishing, ISBN 978-1-921719-07-3

- ^ a b c Hughes, Robert (1988), The fatal shore : a history of the transportation of convicts to Australia 1787-1868, Pan Books Ltd, retrieved 12 June 2020

- ^ "Postscript". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. 25 March 1804. p. 4. Retrieved 21 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ a b c Turbet, Peter (2011). The First Frontier. Dural: Rosenberg. ISBN 978-1-921719073.

- ^ Mackenzie, George (1820). Illustrations of Phrenology. Edinburgh: Constable & Co.

- ^ "GOVERNMENT AND GENERAL ORDERS". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. 10 March 1821. p. 1. Retrieved 14 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "THE BATTLE OF CROPPY'S HILL". Smith's Weekly. 21 November 1925. p. 17. Retrieved 16 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "Early Days of Port Macquarie". The Wingham Chronicle and Manning River Observer. 16 September 1941. p. 4. Retrieved 16 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "SHIPPING INTELLIGENCE". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. 2 December 1824. p. 2. Retrieved 21 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "SHIP NEWS". The Australian. 8 December 1825. p. 3. Retrieved 21 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ Evans, Raymond (5 July 2007), A history of Queensland, Cambridge University Press (published 2007), ISBN 978-0-521-87692-6

- ^ a b c Connor, John (2002), The Australian frontier wars, 1788-1838, University of New South Wales Press, ISBN 978-0-86840-756-2

- ^ O'Sullivan, John (1978), Mounted police in N.S.W, Rigby, ISBN 978-0-7270-0795-7

- ^ Clements, Nicholas (2014), The Black War : fear, sex and resistance in Tasmania, University of Queensland Press, ISBN 978-0-7022-5006-4

- ^ a b c "Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia, 1788-1930". Centre For 21st Century Humanities. University of Newcastle. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Watkins, G (1892). "Notes on the Aborigines of Stradbroke and Moreton Islands". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland. 8: 40–50. doi:10.5962/p.351167. S2CID 257092690.

- ^ "Item ID11936, CSL micro 8 Cluny 12 Jan 1883". Queensland State Archives.

- ^ Evans, R (1999). The Mogwi take Mi-an-jin: race relations and the Moreton Bay penal settlement, 1824-1842. University of Queensland Press. p. 65. ISBN 0958782695.

- ^ "MELANCHOLY OUTRAGES OF THE ABORIGINES OF NEW SOUTH WALES". The Hobart Town Courier. 3 July 1835. p. 4. Retrieved 21 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "The Sydney Herald". The Sydney Herald. 11 June 1835. p. 2. Retrieved 9 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "ADVANCE AUSTRALIA Sydney Gazette". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. 11 June 1835. p. 2. Retrieved 9 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "MATTER FURNISHED BY OUR Reporters and Correspondents". The Sydney Monitor. 15 July 1835. p. 3 (MORNING). Retrieved 9 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ Foster, Robert; Nettelbeck, Amanda (2012), Out of the silence : the history and memory of South Australia's frontier wars, Wakefield Press, ISBN 978-1-74305-039-2

- ^ "His Excellency's late Expedition to the Murchison River". The Perth Gazette and Independent Journal of Politics and News. 30 December 1848. p. 3. Retrieved 21 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "Expedition to the Northward". The Inquirer. 26 December 1849. p. 3. Retrieved 21 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "Quoin Bluff". Western Australian Museum. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Tom Petrie's Reminiscences of Early Queensland. St Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press. 1992. p. 35. ISBN 0702223832.

- ^ "DOMESTIC INTELLIGENCE". The Moreton Bay Courier. 8 December 1849. p. 2. Retrieved 22 April 2019 – via Trove.

- ^ "THE BALLARAT DISTURBANCE". Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer. 20 December 1854. p. 5. Retrieved 17 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "[BY ELECTRIC TELEGRAPH.] [FROM OUR SPECIAL COMMISSIONER.] LAMBING FLAT". The Sydney Morning Herald. 21 February 1861. p. 4. Retrieved 18 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "THE DISTURBANCES AT LAMBING FLAT". The Sydney Morning Herald. 25 February 1861. p. 4. Retrieved 18 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "RIOT AT LAMBING FLAT". The Sydney Morning Herald. 20 July 1861. p. 8. Retrieved 18 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "FATAL COLLISION BETWEEN THE POLICE AND RIOTERS AT LAMBING FLAT". The Star. 19 July 1861. p. 2. Retrieved 18 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "BY ELECTRIC TELEGRAPH". The Sydney Morning Herald. 24 August 1861. p. 4. Retrieved 18 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "DEPARTURE OF THE TROOPS FROM SYDNEY". Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser. 1 September 1870. p. 4. Retrieved 17 June 2020 – via Trove.