Arab conquest of Mesopotamia

| Arab conquest of Mesopotamia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Muslim conquest of Persia | |||||||||

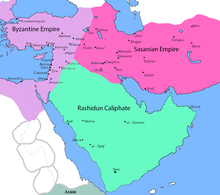

Map of Iran (Persia) and its surrounding regions on the eve of the Muslim invasions | |||||||||

| |||||||||

The Arab conquest of Mesopotamia was carried out by the Rashidun Caliphate from 633 to 638 AD. The Arab Muslim forces of Caliph Umar first attacked Sasanian territory in 633, when Khalid ibn al-Walid invaded Mesopotamia (then known as the Sasanian province of Asōristān; roughly corresponding to modern-day Iraq), which was the political and economic centre of the Sasanian state.[1] From 634 to 636 AD, following the transfer of Khalid to the Byzantine front in the Levant, the hold of Arab forces on the region weakened under the pressure of Sasanian counterattacks. A second major Arab offensive in 636 and ended in January 638 with the capture of Mosul and the consolidation of Arab control over and exclusion of Sasanid influence from the whole Mosul-Tikrit region.

First invasion (633)

[edit]

After the Ridda Wars, a tribal chief of northeastern Arabia, Al-Muthanna ibn Haritha, raided the Sasanian towns in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). Abu Bakr was strong enough to attack the Persian Empire in the north-east and the Byzantine Empire in the north-west. There were three purposes for this conquest. First, along the border between Arabia and these two great empires were numerous nomadic Arab tribes serving as a buffer between the Persians and Romans. Abu Bakr hoped that these tribes might accept Islam and help their brethren in spreading it. Second, the Persian and Roman populations were very highly taxed; Abu Bakr believed that they might be persuaded to help the Muslims, who agreed to release them from the excessive tributes. Finally, Abu Bakr hoped that by attacking Iraq and Syria he might remove the danger from the borders of the Islamic State.[2] With the success of the raids, a considerable amount of booty was collected. Al-Muthanna ibn Haritha went to Medina to inform Abu Bakr about his success and was appointed commander of his people, after which he began to raid deeper into Mesopotamia. Using the mobility of his light cavalry, he could easily raid any town near the desert and disappear again into the desert, beyond the reach of the Sasanian army. Al-Muthanna's acts made Abu Bakr think about the expansion of the Rashidun Caliphate.[3]

To ensure victory, Abu Bakr used a volunteer army and put his best general, Khalid ibn al-Walid, in command. After defeating the self-proclaimed prophet Musaylimah in the Battle of Yamama, Khalid was still at Al-Yamama when Abu Bakr ordered him to invade the Sasanian Empire. Making Al-Hirah the objective of Khalid, Abu Bakr sent reinforcements and ordered the tribal chiefs of northeastern Arabia, Al-Muthanna ibn Haritha, Mazhur bin Adi, Harmala and Sulma to operate under Khalid's command. Around the third week of March 633 (first week of Muharram 12th Hijrah) Khalid set out from Al-Yamama with an army of 10,000.[3] The tribal chiefs, with 2,000 warriors each, joined him, swelling his ranks to 18,000.

After entering Mesopotamia, he dispatched messages to every governor and deputy who ruled the provinces. The messages said; “In the Name of God, the Most Compassionate and Merciful. Khalid ibn Walid sends this message to the satraps of Persia. Peace will be upon him who follows the guidance. All praise and thanks be to God who disperses your power and thwarted your deceitful plots. On the one hand, he who performs our prayers facing the direction of our Qiblah to face the sacred Mosque in Mekkah and eats our slaughtered animals is a Muslim. He has the same rights and duties that we have. On the other hand, if you do not want to embrace Islam, then as soon as you receive this message, send over the jizya and I give you my word that I will respect and honor this covenant. But if you do not agree to either choice, then, by God, I will send to you people who crave death as much as you crave life.” [4] Khalid did not receive any responses and continued with his tactical plans.

Khalid won decisive victories in four consecutive battles: the Battle of Chains, fought in April; the Battle of River, fought in the third week of April; the Battle of Walaja the following month (where he successfully used a double envelopment manoeuvre), and the Battle of Ullais, fought in mid-May. The Persian court, already disturbed by internal problems, was thrown into chaos. In the last week of May, the important city of Hira fell to the Muslims. After resting his armies, in June, Khalid laid siege to the city of al-Anbar, which surrendered in July. Khalid then moved south, and conquered the city of Ayn al-Tamr in the last week of July.

Battle of Chains

[edit]

Movement of Khalid ibn Walid's army and the Sassanid army before the battle. Khalid's strategy was to wear out the Sassanid army.

The Battle of Chains was the first battle fought between the Rashidun Caliphate and the Sasanian Empire, and was fought in Kazima in April 633. In approximately the third week of March 633 AD, Khalid set out from Yamama with an army of 10,000 men.[5] According to Tabari, Khalid was then joined by various tribal chiefs and their warriors, to the point that Khalid entered the Sasanian territory with 18,000 troops.[6] Expecting Khalid ibn al-Walid to come though Kazima, the Sasanian commander Hormozd Jadhuyih marched from Uballa to Kazima, where his scouts informed him that the Arab forces were instead moving towards Hufeir, a settlement only 21 miles from Uballa, in a threat to the Sasanian base, so Hormozd immediately ordered a move to Hufeir, 50 miles away. Upon his scouts informed him about the Sasanian approach, Khalid passed back through the desert towards Kazima. The heavily armed Sassanid army was once again updated by its scouts and about-turned to Kazima, but by the time the Sasanian troops arrived at Kazima they were in a state of exhaustion.

As battle was joined, Hormozd deployed the Sassanid army in a typical set-piece battle formation with himself at the centre and two of his generals, Qubaz and Anoshagan, commanding his wings. According to Tabari, the Persian troops linked themselves together with chains as a defense against cavalry attacks and as a sign to the enemy that they were ready to die rather than to run away from the battle field in case of defeat. But the chains had one major drawback: in case of defeat the men were incapable of withdrawal, for then the chains acted as fetters. It was the use of chains that gave this battle its name.[7] In the event, the exhausted Persian army was unable to stand the attack for long and the Muslims successfully penetrated the Persian front in many places. Sensing defeat, the Persian generals commanding the wings, Qubaz and Anoshagan, ordered a withdrawal, which led to a general retreat. Most of the Persians who were not chained managed to escape, but those who were chained together were unable to move fast, and thousands of them were slain.

Battle of River

[edit]Battle of Walaja

[edit]Battle of Ullais

[edit]

After their defeat at the Battle of Walaja, the Sassanid survivors of the battle who consisted mostly of Christian Arabs fled from the battlefield, crossed the River Khaseef (a tributary of the Euphrates) and moved between it and the Euphrates.[8][9] Their flight ended at Ullais, about 10 miles from the location of the Battle of Walaja, and 25 miles south-east of the Iraqi city of Najaf.[10] Here the Sasanian army received reinforcements from the Christian Arab tribe of Bani Bakr and other tribes in the region between Al-Hirah and Ullais, leading Khalid to crossthe river Khaseef with the Rashidun army and assault Ullais frontally.[11] Emperor Yazdegerd III meanwhile sent orders to Bahman Jaduya to proceed to Ullais and take command of Arab contingents there and stop the Muslims advance at Ullais.[12] It is estimated that the Sasanid army ultimately numbered 30,000 men.[13] When battle was joined, Tabari records that the Arab forces were initially unable to break through Sasanian lines. According to the narrative, Khalid then prayed to Allah and promised that he would flow rivers of blood if he won the battle. The tide of the battle turned, and the assaults of the Arab forces eventually broke the Sasanian morale and the Iranian troops started fleeing towards Al-Hirah. Thousands were killed, with the banks of the river turning red from the amount of dead, this fulfilling Khalid's oath.[14][9][15] The Sasanian commander Jaban however escaped.[9][16]

Battle of Hira

[edit]The Battle of Hira was enjoined soon after the Battle of Ullais in May, with the Arab forces under Khalid ibn al-Walid attacking Hira in the last week of the same month. The defenders briefly sequestered themselves in the city's fortresses, but after brief fighting, the city quickly surrendered.[17][18] The inhabitants paid a large tribute[19] to spare the city, and agreed to act as spies against the Sasanians, just as the inhabitants of Ullais had.[20]

Battle of al-Anbar

[edit]The Battle of al-Anbar took place at Anbar which is located approximately 80 miles from the ancient city of Babylon. Khalid besieged the Sassanian Persians in the city fortress, which had strong walls. Scores of Muslim archers were used in the siege. The Persian governor, Shirzad, eventually surrendered and was allowed to retire.[21] The Battle of Al-Anbar is often remembered as the "Action of the Eye"[21] since Muslim archers used in the battle were told to aim at the "eyes" of the Persian garrison.[21]

Battle of Ayn al-Tamr

[edit]The Battle of Ayn al-Tamr was enjoined at Ayn al-Tamr, which is located west of Anbar and was a frontier post which had been established to aid the Sassanids.[22] In the engagement, the Muslims under Khalid ibn al-Walid's command again soundly defeated the Sassanian auxiliary force, which included large numbers of non-Muslim Arabs who broke earlier covenants with the Muslims.[23] According to William Muir, Khalid ibn al-Walid captured the Arab Christian commander, Aqqa ibn Qays ibn Bashir, with his own hands,[24] which matched the accounts of both Ibn Atheer in his Usd al-ghabah fi marifat al-Saḥabah, and Tabari in his Tarikh.[25][26] At this point, most of what is now Iraq was under Islamic control.

Battle of Dawmat al-Jandal

[edit]At this point, Khalid received a call for aid from northern Arabia at Dawmat al-Jandal, where another Muslim Arab general, Iyad ibn Ghanm, was trapped among the rebel tribes. Khalid went there and defeated the rebels in the Battle of Dawmat al-Jandal in the last week of August. Upon his return, he received news of the assembling of a large Persian army. He decided to divide his forces and intercept the regathering Sasanid forces rather than risk of being defeated by a large unified army. The different divisions of Persian and Christian Arab auxiliaries were present at Husayd, Muzayyah, Saniyy and Zumail.[27]

Battle of Husayd

[edit]The Battle of Husayd occurred as a side skirmish that saw a detachment of Rashidun forces under Al-Qa'qa' ibn Amr al-Tamimi intercept a combined force of local Arab Christians and Sasanian army detachments.[28][29][30][31] The local tribes had already been defeated at the Battle of Al-Anbar and rallied to the Sasanian banner at the prospect of revenge.[32][29] The Rashidun army nevertheless soundly defeated the combined army once again, to the extent that all of the opposing commanders were slain.[32][29][30] A separate detachment had headed to Khanafis at the same time to scout for other local or Sasanid forces, but encountered no resistance.[28]

Battles of Muzayyah, Saniyy and Zumail

[edit]After the separated detachments had rejoined Khalid's main forces, he moved on Muzayyah.[33] Khalid divided his army into three units, and employed them in well-coordinated attacks against the Persians from three different sides at night, in the Battle of Muzayyah, then the Battle of Saniyy, and finally the Battle of Zumail, all during the month of November. These devastating defeats ended Persian control over Mesopotamia, and left the Persian capital Ctesiphon vulnerable. Before attacking Ctesiphon, Khalid decided to eliminate all Persian forces in the south and west. He accordingly marched against the border city of Firaz, where he defeated the combined forces of the Sasanian Persians, the Byzantines and Christian Arabs in December. This was the last battle in his conquest of Mesopotamia. While Khalid was on his way to attack Qadissiyah (a key fort en route to Ctesiphon), Abu Bakr ordered him to the Roman front in Syria to assume command there.[34]

Second invasion (634–636)

[edit]Battle of the Bridge

[edit]According to the will of Abu Bakr, Umar was to continue the conquest of Syria and Mesopotamia. On the northeastern borders of the Empire, in Mesopotamia, the situation was rapidly deteriorating. During Abu Bakr's era, Khalid ibn al-Walid had left Mesopotamia with half his army of 9000 soldiers to assume command in Syria, whereupon the Persians decided to take back their lost territory. The Muslim army was forced to leave the conquered areas and concentrate on the border. Umar immediately sent reinforcements to aid Muthanna ibn Haritha in Mesopotamia under the command of Abu Ubaid al-Thaqafi.[35] At that time, a series of battles between the Persians and Arabs occurred in the region of Sawad, such as Namaraq, Kaskar and Baqusiatha, in which the Arabs managed to maintain their presence in the area.[36] Later on, the Persians defeated Abu Ubaid in the Battle of the Bridge. Muthanna bin Haritha was later victorious in the Battle of Buwayb. In 635 Yazdgerd III sought an alliance with Emperor Heraclius of the Eastern Roman Empire, marrying the latter's daughter (or, by some traditions, his granddaughter) in order to seal the arrangement. While Heraclius prepared for a major offence in the Levant, Yazdegerd ordered the concentration of massive armies to push the Muslims out of Mesopotamia for good through a series of well-coordinated attacks on two fronts.

Battle of Qadisiyyah

[edit]Umar ordered his army to retreat to the Arabian border and began raising armies at Medina for another campaign into Mesopotamia. Owing to the critical situation, Umar wished to command the army personally, but the members of Majlis ash-Shura demurred, claiming that the two-front war required Umar's presence in Medina. Accordingly, Umar appointed Saad ibn Abi Waqqas, a respected senior officer, even though Saad was suffering from sciatica.[37] Saad left Medina with his army in May 636 and arrived at Qadisiyyah in June.

While Heraclius launched his offensive in May 636, Yazdegerd was unable to muster his armies in time to provide the Byzantines with Persian support. Umar, allegedly aware of this alliance and not wanting to risk a battle with two great powers simultaneously, quickly reinforced the Muslim army at Yarmouk to engage and defeat the Byzantines. Meanwhile, he ordered Saad to enter into peace negotiations with Yazdegerd III and invite him to convert to Islam to prevent Persian forces from taking the field. Heraclius instructed his general Vahan not to engage in battle with the Muslims before receiving explicit orders. Fearing more Arab reinforcements, Vahan attacked the Muslim army in the Battle of Yarmouk in August 636, and was routed.[38]

With the Byzantine threat ended, the Sasanian Empire was still a formidable power with vast manpower reserves, and the Arabs soon found themselves confronting a huge Persian army with troops drawn from every corner of the empire, including war elephants, and commanded by its foremost generals. Within three months, Saad defeated the Persian army in the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah, effectively ending Sasanian rule west of Persia proper.[39] This victory is largely regarded as a decisive turning point in Islam's growth: with the bulk of Persian forces defeated, Saad with his companions later conquered Babylon (Battle of Babylon (636)), Kūthā, Sābāṭ (Valashabad) and Bahurasīr (Veh-Ardashir). Ctesiphon, the capital of the Sassanid Empire, fell in March 637 after a siege of three months.

Final campaign and conquest (636–638)

[edit]In December 636, Umar ordered Utbah ibn Ghazwan to head south to capture al-Ubulla (known as "port of Apologos" in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea) and Basra, in order to cut ties between the Persian garrison there and Ctesiphon. Utbah ibn Ghazwan arrived in April 637, and captured the region. The Persians withdrew to the Maysan region, which the Muslims seized later as well.[40]

After the conquest of Ctesiphon, several detachments were immediately sent west to capture Circesium and Heet, both forts at the Byzantine border. Several fortified Persian armies were still active north-east of Ctesiphon at Jalawla and north of the Tigris at Tikrit and Mosul.

After withdrawal from Ctesiphon, the Persian armies gathered at Jalawla, a place of strategic importance due to routes leading from here to Mesopotamia, Khurasan and Azerbaijan. The Persian forces at Jalawla were commanded by Mihran. His deputy was Farrukhzad, a brother of Rustam, who had commanded the Persian forces at the Battle of al-Qadisiyyah. Umar decided to deal with Jalawla first, thereby clearing the way to the north, before taking any decisive action against Tikrit and Mosul. Umar appointed Hashim ibn Utbah to take Jalawla and Abdullah ibn Muta'am to conquer Tikrit and Mosul. In April 637, Hashim led 12,000 troops from Ctesiphon to win a victory over the Persians at the Battle of Jalawla. He then laid siege to Jalawla for seven months, ending in the city's capture. Then, Abdullah ibn Muta'am marched against Tikrit and captured the city with the help of Christians, after fierce resistance.[citation needed] He next sent an army to Mosul which surrendered on the condition of paying Jizya. With victory at Jalawla and occupation of the Tikrit-Mosul region, the whole of Mesopotamia was under Muslim control.

Thereafter, a Muslim force under Qa'qa marched in pursuit of the escaping Persians at Khaniqeen, 25 kilometres (15 mi) from Jalawla on the road to Iran, still under the command of Mihran. Qa'qa defeated the Persian forces in the Battle of Khaniqeen and captured the city. The Persians then withdrew to Hulwan. Qa'qa followed and laid siege to the city, which was captured in January 638.[41] Qa'qa sought permission to operate deeper in Persia, but Umar rejected the proposal, writing in response:

I wish that between the Suwad and the Persian hills there were walls which would prevent them from getting to us, and prevent us from getting to them.[42] The fertile Suwad is sufficient for us; and I prefer the safety of the Muslims to the spoils of war.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Stephen Humphreys, R. (January 1999). Between Memory and Desire. University of California Press. p. 180. ISBN 9780520214118 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Akbar Shah Najeebabadi, The history of Islam. B0006RTNB4.

- ^ a b Tabari: Vol. 2, p. 554.

- ^ Khalid. Men Around the Messenger. Al Manar. p. 234.

- ^ Parvaneh Pourshariati, The Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire, 192.

- ^ Tabari: Vol. 2, p. 554.

- ^ Tabari: Vol. 3, p. 206.

- ^ Tabari Vol. 2, P. 560

- ^ a b c Agha Ibrahim Akram (2009). "22:The River of Blood". The Sword of Allah: Khalid Bin Al-Waleed, His Life and Campaigns. Adam Publishers. p. 254-263. ISBN 9788174355218.

- ^ The Sword of Allah”: Chapter no: Chapter 22: page no:1 by Lieutenant-General Agha Ibrahim Akram, Nat. Publishing. House, Rawalpindi (1970) ISBN 978-0-7101-0104-4.

- ^ Tabari: Vol. 2, p. 562

- ^ Tabari: Vol. 2, p. 560.

- ^ Crawford 2013, p. 105.

- ^ al-Tabari, tr. by Khalid Yahya Blankinship (January 1993). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 11: The Challenge to the Empires A.D. 633-635/A.H. 12-13. SUNY Press. p. 21-26. ISBN 9780791408513.

- ^ Tabari. History of Tabari (Persian). Vol. 4. Asatir Publishers, Third Edition, 1984. p. 1493-1503.

- ^ William Bayne Fisher; Richard Nelson Frye; Peter Avery; John Andrew Boyle; Ilya Gershevitch; Peter Jackson, eds. (26 June 1975). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 7-8. ISBN 9780521200936.

- ^ Hitti, Origins of the Islamic State (translation of Kitab Futuh Al-Buldan); It is reported that Yazid ibn-Nubaishah-l-'Armiri said "... We then came to al-Hirah whose people had fortified themselves in al-Kasr al-Abyad, Kasr ibn-Bukailah and Kasr al'Adasiyin. We went around on horseback in the open spaces among their buildings, after which they made terms with us.", p. 391

- ^ Muir, The Caliphate, Its Rise, Decline, and Fall. From Original Sources, p. 56

- ^ Hitti, Origins of the Islamic State (translation of Kitab Futuh Al-Buldan); Al Husain ibn-al-Aswad from Yahya ibn-Adam: "I heard it said that the people of al-Hirah were 6000 men, on each one of whom 14 dirhams ... were assessed, making 84000 dirhams in all.", p. 391

- ^ Morony 2005, p. 233.

- ^ a b c Annals of the Early Caliphate By William Muir, pg 85

- ^ The Caliph's Last Heritage: A Short History of the Turkish Empire by Mark Sykes

- ^ The Book of Revenue: Kitab Al-Amwal by Abu 'Ubayd Al-Qasim Ibn Sallam, pg 194

- ^ Muir 1883, p. 62.

- ^ Ibn Atheer.

- ^ Tabari 1993, p. 53-54.

- ^ Tabari & Blankinship 1993, p. 57-60.

- ^ a b Tabari & Blankinship 1993, p. 61-62.

- ^ a b c Al-Maghlouth 2006, p. 84.

- ^ a b Quraibi 2016, p. 280.

- ^ Donner 2014, p. 470.

- ^ a b Tabari & Blankinship 1993, p. 61-63.

- ^ Tabari & Blankinship 1993, p. 62.

- ^ Akram, chapters 19–26.

- ^ The Muslim Conquest of Persia By A.I. Akram. Ch: 1 ISBN 978-0-19-597713-4

- ^ نجاة سليم محاسيس (2011). معجم المعارك التاريخية (in Arabic). Al Manhal. p. 285. ISBN 9796500011615.

- ^ "Taqawa Leads to Success: Saad Bin Abi Waqqas RaziAllah Unho". Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Serat-i-Hazrat Umar-i-Farooq, by Mohammad Allias Aadil, page no:67

- ^ Akram, A.I. (1975). "5". The Muslim Conquest of Persia. ISBN 978-0-19-597713-4.

- ^ Al-Tabari. History of the Prophets and Kings. pp. 590–595.

- ^ Akram, A. I. (1975). "6". The Muslim Conquest of Persia. ISBN 978-0-19-597713-4.

- ^ Haykal, Muhammad Husayn. "5". Al Farooq, Umar. p. 130.

Sources

[edit]- Al-Maghlouth, Sami ibn Abd allah ibn Ahmad (2006). Atlas of Caliph Abu Bakr. p. 84. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- Crawford, Peter (16 July 2013). The War of the Three Gods: Romans, Persians and the Rise of Islam. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84884-612-8.

- Donner, Fred (2014). The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton University Press. p. 370. ISBN 9781400847877. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- Ibn Atheer, Ali. "Usd al-ghabah fi marifat al-Saḥabah". Wikisource. Wikipedia. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- Morony, Michael G. (2005). Iraq After the Muslim Conquest. Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-15-93333-15-7.

- Muir, William (1883). Annals of the Early Caliphate From Original Sources. Smith, Elder & Company. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-598-54156-7. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- Tabari, Muhammad Ibn Jarir (1993). The challenge to the empires (Khalid Yahya Blankinship ed.). State University of New York Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 9780791408513. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- Quraibi, Ibrahim (2016). Tarikh Khulafa(history of the caliphs). Qisthi Press. p. 280. ISBN 9789791303408. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir; Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1993). The History of al-Tabari vol. 11 (Khalid Yahya Blankinship ed.). State university of New York press. pp. 61–63. Retrieved 21 October 2021.