History of Jerusalem

| Part of a series on |

| Jerusalem |

|---|

|

| History of Israel |

|---|

|

|

|

Jerusalem is one of the world's oldest cities, with a history spanning over 5,000 years. Its origins trace back to around 3000 BCE, with the first settlement near the Gihon Spring. The city is first mentioned in Egyptian execration texts around 2000 BCE as "Rusalimum." By the 17th century BCE, Jerusalem had developed into a fortified city under Canaanite rule, with massive walls protecting its water system. During the Late Bronze Age, Jerusalem became a vassal of Ancient Egypt, as documented in the Amarna letters.

The city's importance grew during the Israelite period, which began around 1000 BCE when King David captured Jerusalem and made it the capital of the united Kingdom of Israel. David's son, Solomon, built the First Temple, establishing the city as a major religious center. Following the kingdom's split, Jerusalem became the capital of the Kingdom of Judah until it was captured by the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 586 BCE. The Babylonians destroyed the First Temple, leading to the Babylonian exile of the Jewish population. After the Persian conquest of Babylon in 539 BCE, Cyrus the Great allowed the Jews to return and rebuild the city and its temple, marking the start of the Second Temple period. Jerusalem fell under Hellenistic rule after the conquests of Alexander the Great in 332 BCE, leading to increasing cultural and political influence from Greece. The Hasmonean revolt in 1the 2nd century BCE briefly restored Jewish autonomy, with Jerusalem as the capital of an independent state.

In 63 BCE, Jerusalem was conquered by Pompey and became part of the Roman Empire. The city remained under Roman control until the Jewish–Roman wars, which culminated in the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. The city was renamed Aelia Capitolina and rebuilt as a Roman colony after the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 CE), with Jews banned from entering the city. Jerusalem gained significance during the Byzantine Empire as a center of Christianity, particularly after Constantine the Great endorsed the construction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. In 638 CE, Jerusalem was conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate, and under early Islamic rule, the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque were built, solidifying its religious importance in Islam. During the Crusades, Jerusalem changed hands multiple times, being captured by the Crusaders in 1099 and recaptured by Saladin in 1187. It remained under Islamic control through the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods, until it became part of the Ottoman Empire in 1517.

In the modern period, Jerusalem was divided between Israel and Jordan after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. Israel captured East Jerusalem during the Six-Day War in 1967, uniting the city under Israeli control. The status of Jerusalem remains a highly contentious issue, with both Israelis and Palestinians claiming it as their capital. Historiographically, the city's history is often interpreted through the lens of competing national narratives. Israeli scholars emphasize the ancient Jewish connection to the city, while Palestinian narratives highlight the city's broader historical and multicultural significance. Both perspectives influence contemporary discussions of Jerusalem's status and future.

Ancient period

Proto-Canaanite period

Archaeological evidence suggests that the first settlement was established near Gihon Spring between 3000 and 2800 BCE. The first known mention of the city was in c. 2000 BCE in the Middle Kingdom Egyptian execration texts in which the city was recorded as Rusalimum.[1][2] The root S-L-M in the name is thought to refer to either "peace" (compare with modern Salam or Shalom in modern Arabic and Hebrew) or Shalim, the god of dusk in the Canaanite religion.

Canaanite and Egyptian period

Archaeological evidence suggests that by the 17th century BCE, the Canaanites had built massive walls (4 and 5 ton boulders, 26 feet high) on the eastern side of Jerusalem to protect their ancient water system.[3][better source needed] By c. 1550–1400 BCE, Jerusalem had become a vassal to Egypt after the Egyptian New Kingdom under Ahmose I and Thutmose I had reunited Egypt and expanded into the Levant. The Amarna letters contain correspondence from Abdi-Heba, headman[4] of Urusalim and his suzerain Amenhotep III.

The power of the Egyptians in the region began to decline in the 12th century BCE, during the Late Bronze Age collapse. The Battle of Djahy (Djahy being the Egyptian name for Canaan) in 1178 BCE between Ramesses III and the Sea Peoples marks this loss of power, preceded by the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE, which by extension may be said to be marking the beginning of the decline of both the Egyptians and the Hittites (then particularly the Ha'atussa-Wilussa circuit of Anatolian city-states). The decline of these central powers gave rise to more independent kingdoms in the region. According to the Bible, Jerusalem at this time was known as Jebus, and its independent Canaanite inhabitants at this time were known as Jebusites.

Israelite period

According to the Bible, the Israelite history of the city began in c. 1000 BCE, with King David's sack of Jerusalem, following which Jerusalem became the City of David and capital of the united Kingdom of Israel.[1] According to the Books of Samuel, the Jebusites managed to resist attempts by the Israelites to capture the city and by the time of King David were mocking such attempts, claiming that even the blind and lame could defeat the Israelite army. Nevertheless, the masoretic text for the Books of Samuel states that David managed to capture the city by stealth, sending his forces through a "water shaft" and attacking the city from the inside. Archaeologists now view this as implausible as the Gihon spring – the only known location from which water shafts lead into the city – is now known to have been heavily defended (and hence an attack via this route would have been obvious rather than secretive). The older[citation needed] Septuagint text, however, suggests that rather than by a water shaft, David's forces defeated the Jebusites by using daggers. There was another king in Jerusalem, Araunah, during and possibly before David's control of the city,[5] who was probably the Jebusite king of Jerusalem.[6] The city, which at that point stood upon the Ophel, was expanded to the south and declared by David to be the capital city of the Kingdom of Israel. David also constructed an altar at the location of a threshing floor he had purchased from Araunah; a portion of biblical scholars view this as an attempt by the narrative's author to give an Israelite foundation to a pre-existing sanctuary.[7]

Later, King Solomon built a more substantive temple, the Temple of Solomon, at a location which the Books of Chronicles equates with David's altar. The temple became a major cultural centre in the region; eventually, particularly after religious reforms such as those of Hezekiah and of Josiah, the temple became the main place of worship, at the expense of other, formerly powerful, ritual centres such as Shiloh and Bethel. However, according to K. L. Noll, in Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: A Textbook on History and Religion, the biblical account of the centralization of worship in Jerusalem is a fiction, although by the time of Josiah the territory he ruled was so small that the temple became de facto the only shrine left.[8] Solomon is also described as having created several other important building works at Jerusalem, including the construction of his palace, and the construction of the Millo (the identity of which is somewhat controversial). Archaeologists are divided over whether the biblical narrative is supported by the evidence from excavations.[9] Eilat Mazar contends that her digging uncovered remains of large stone buildings from the correct time period, while Israel Finkelstein disputes both the interpretation and the dating of the finds.[10][11]

When the Kingdom of Judah split from the larger Kingdom of Israel (which the Bible places near the end of the reign of Solomon, c. 930 BCE, though Finkelstein and others dispute the very existence of a unified monarchy to begin with[12]), Jerusalem became the capital of the Kingdom of Judah, while the Kingdom of Israel located its capital at Shechem in Samaria. Thomas L. Thompson argues that it only became a city and capable of acting as a state capital in the middle of the 7th century BCE.[13] However, Omer Sergi argues that recent archaeological discoveries at the City of David and the Ophel seem to indicate that Jerusalem was already a significant city by the Iron Age IIA.[14]

Both the Bible and regional archaeological evidence suggest the region was politically unstable during the period 925–732 BCE. In 925 BCE, the region was invaded by Egyptian Pharaoh Sheshonk I of the Third Intermediate Period, who is possibly the same as Shishak, the first Pharaoh mentioned in the Bible who captured and pillaged Jerusalem. Around 75 years later, Jerusalem's forces were likely involved in an indecisive battle against the Neo-Assyrian King Shalmaneser III in the Battle of Qarqar. According to the Bible, Jehoshaphat of Judah was allied to Ahab of the Kingdom of Israel at this time. The Bible records that shortly after this battle, Jerusalem was sacked by Philistines, Arabs and Ethiopians, who looted King Jehoram's house and carried off all of his family except for his youngest son Jehoahaz.

Two decades later, most of Canaan including Jerusalem was conquered by Hazael of Aram-Damascus. According to the Bible, Jehoash of Judah gave all of Jerusalem's treasures as a tribute, but Hazael proceeded to destroy "all the princes of the people" in the city. And half a century later, the city was sacked by Jehoash of Israel, who destroyed the walls and took Amaziah of Judah prisoner.

By the end of the First Temple Period, Jerusalem was the sole acting religious shrine in the kingdom and a centre of regular pilgrimage; a fact which archaeologists generally view as being corroborated by the evidence,[citation needed] though there remained a more personal cult involving Asherah figures, which are found spread throughout the land right up to the end of this era.[12]

Assyrian and Babylonian periods

Jerusalem was the capital of the Kingdom of Judah for some 400 years. It had survived an Assyrian siege in 701 BCE by Sennacherib, unlike Samaria, which had fallen some 20 years previously. According to the Bible, this was a miraculous event in which an angel killed 185,000 men in Sennacherib's army. According to Sennacherib's own account preserved in the Taylor prism, an inscription contemporary with the event, the king of Judah, Hezekiah, was "shut up in the city like a caged bird" and eventually persuaded Sennacherib to leave by sending him "30 talents of gold and 800 talents of silver, and diverse treasures, a rich and immense booty".

The siege of Jerusalem in 597 BCE led to the city being overcome by the Babylonians, who then took the young King Jehoiachin into Babylonian captivity, together with most of the aristocracy. Zedekiah, who had been placed on the throne by Nebuchadnezzar (the Babylonian king), rebelled, and Nebuchadnezzar recaptured the city, killed Zedekiah's descendants in front of him, and plucked out Zedekiah's eyes so that that would be the last thing he ever saw. The Babylonians then took Zedekiah into captivity, along with prominent members of Judah. The Babylonians then burnt the temple, destroyed the city's walls, and appointed Gedaliah son of Achikam as governor of Judah. After 52 days of rule, Yishmael, son of Netaniah, a surviving descendant of Zedekiah, assassinated Gedaliah after encouragement by Baalis, the king of Ammon. Some of the remaining population of Judah, fearing the vengeance of Nebuchadnezzar, fled to Egypt.

Persian (Achaemenid) period

According to the Bible and perhaps corroborated by the Cyrus Cylinder, after several decades of captivity in Babylon and the Achaemenid conquest of Babylonia, Cyrus II of Persia allowed the Jews to return to Judah and rebuild the temple. The books of Ezra–Nehemiah record that the construction of the Second Temple was finished in the sixth year of Darius the Great (516 BCE), following which Artaxerxes I sent Ezra and then Nehemiah to rebuild the city's walls and to govern the Yehud province within the Eber-Nari satrapy. These events represent the final chapter in the historical narrative of the Hebrew Bible.[15]

During this period, Aramaic-inscribed "Yehud coinage" were produced – these are believed to have been minted in or near Jerusalem, although none of the coins bear a mint mark.

Classical antiquity

Hellenistic period

Ptolemaic and Seleucid province

When Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire, Jerusalem and Judea fell under Greek control and Hellenistic influence. After the Wars of the Diadochoi following Alexander's death, Jerusalem and Judea fell under Ptolemaic control under Ptolemy I and continued minting Yehud coinage. In 198 BCE, as a result of the Battle of Panium, Ptolemy V lost Jerusalem and Judea to the Seleucids under Antiochus the Great.

Under the Seleucids many Jews had become Hellenized and with their assistance tried to Hellenize Jerusalem, eventually culminating in the 160s BCE in a rebellion led by Mattathias and his five sons: Simon, Yochanan, Eleazar, Jonathan and Judas Maccabeus, also known as the Maccabees. After Mattathias died, Judas Maccabee took over as the revolt's leader, and in 164 BCE, he captured Jerusalem and restored temple worship, an event celebrated to this day in the Jewish festival of Hanukkah.[16][17]

Hasmonean period

As a result of the Maccabean Revolt, Jerusalem became the capital of the autonomous and eventually independent Hasmonean state which lasted for over a century. After Judas' death, his brothers Jonathan Apphus and Simon Thassi were successful in creating and consolidating the state. They were succeeded by John Hyrcanus, Simon's son, who won independence, enlarged Judea's borders, and began minting coins. Hasmonean Judea became a kingdom and continued to expand under his sons kings Aristobulus I and subsequently Alexander Jannaeus. When his widow Salome Alexandra died in 67 BCE her sons Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II fought among themselves over who would succeed her. In order to resolve their dispute, the parties involved turned to Roman general Pompey, who paved the way for a Roman takeover of Judea.[18]

Pompey supported Hyrcanus II over his brother Aristobulus II who then controlled Jerusalem, and the city was soon under siege. Upon his victory, Pompey desecrated the Temple by entering the Holy of Holies, which could only be done by the High Priest. Hyrcanus II was restored as High Priest, stripped of his royal title but recognized as an ethnarch in 47 BCE. Judea remained an autonomous province but still with a significant amount of independence. The last Hasmonean king was Aristobulus' son, Antigonus II Matityahu.

Early Roman period

In 37 BCE, Herod the Great captured Jerusalem after a forty-day siege, ending Hasmonean rule. Herod ruled the Province of Judea as a client-king of the Romans, rebuilt the Second Temple, more than doubled the size of the surrounding complex, and expanded the minting of coins to many denominations. The Temple Mount became the largest temenos (religious sanctuary) in the ancient world.[19] Pliny the Elder, writing of Herod's achievements, called Jerusalem "the most famous by far of the Eastern cities and not only the cities of Judea." The Talmud comments that "He who has not seen the Temple of Herod has never seen a beautiful building in his life." And Tacitus wrote that "Jerusalem is the capital of the Jews. In it was a Temple possessing enormous riches."[20]

Herod also built Caesarea Maritima which replaced Jerusalem as the capital of the Roman province.[Note 1] In 6 CE, following Herod's death in 4 BCE, Judea and the city of Jerusalem came under direct Roman rule through Roman prefects, procurators, and legates (see List of Hasmonean and Herodian rulers). However, one of Herod's descendants was the last one to return to power as nominal king of Iudaea Province: Agrippa I (r. 41–44).

In the 1st century CE, Jerusalem became the birthplace of Early Christianity. According to the New Testament, it is the location of the crucifixion, resurrection and Ascension of Jesus Christ (see also Jerusalem in Christianity). It was in Jerusalem that, according to the Acts of the Apostles, the Apostles of Christ received the Holy Spirit at Pentecost and first began preaching the Gospel and proclaiming his resurrection. Jerusalem eventually became an early center of Christianity and home to one of the five Patriarchates of the Christian Church. After the Great Schism, it remained a part of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

By the end of the Second Temple period, Jerusalem's size and population had reached a peak that would not be broken until the 20th century. There were about 70,000- 100,000 people living in the city at that time, according to modern estimations.[22]

Jewish–Roman Wars

In 66 CE, the Jewish population in the Roman province of Judaea rebelled against the Roman Empire in what is now known as the First Jewish–Roman War or Great Revolt. Jerusalem was then the center of Jewish rebel resistance. Following a brutal five-month siege, Roman legions under future emperor Titus reconquered and subsequently destroyed much of Jerusalem in 70 CE.[23][24][25] Also the Second Temple was burnt and all that remained was the great external (retaining) walls supporting the esplanade on which the Temple had stood, a portion of which has become known as the Western Wall. Titus' victory is commemorated by the Arch of Titus in Rome. This victory gave the Flavian dynasty legitimacy to claim control over the empire. A triumph was held in Rome to celebrate the fall of Jerusalem, and two triumphal arches, including the well known Arch of Titus, were built to commemorate it. The treasures looted from the Temple were put on display.[26]

Jerusalem was later re-founded and rebuilt as the Roman colony of Aelia Capitolina. Foreign cults were introduced and Jews were forbidden entry.[27][28][29] The construction of Aelia Capitolina is considered one of the proximate reasons for the eruption of the Bar Kokhba revolt in 132 CE.[30][31] Early victories allowed the Jews under the leadership of Simon bar Kokhba to establish an independent state over much of Judea for three years, but it's uncertain if they would also assert their control over Jerusalem. Archaeological research found no evidence for Bar Kokhba ever managing to hold the city.[32] Hadrian responded with overwhelming force, putting down the rebellion, killing as many as a half million Jews, and resettling the city as a Roman colonia. Jews were expelled from the area of Jerusalem,[33] and were forbidden to enter the city on the pain of death, except on the day of Tisha B'Av (the Ninth of Av), the fast day on which Jews mourn the destruction of both Temples.[34]

Late antiquity

Late Roman period

Aelia Capitolina of the Late Roman period was a Roman colony, with all the typical institutions and symbols - a forum, and temples to the Roman gods. Hadrian placed the city's main forum at the junction of the main Cardo and Decumanus, now the location of the (smaller) Muristan. He also built a large temple to Jupiter Capitolinus, which later became the site of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.[35] The city had no walls, was protected by a light garrison of the Tenth Legion. For the next two centuries, the city remained a relatively unimportant pagan Roman town.

A Roman legionary tomb at Manahat, the remains of Roman villas at Ein Yael and Ramat Rachel, and the Tenth Legion's kilns found close to Giv'at Ram, all within the borders of modern-day Jerusalem, are all signs that the rural area surrounding Aelia Capitolina underwent a romanization process, with Roman citizens and Roman veterans settling in the area during the Late Roman period.[36] Jews were still banned from the city throughout the remainder of its time as a Roman province.

Byzantine period

Following the Christianization of the Roman Empire, Jerusalem prospered as a hub of Christian worship. After allegedly seeing a vision of a cross in the sky in 312, Constantine the Great began to favor Christianity, signed the Edict of Milan legalizing the religion, and sent his mother, Helena, to Jerusalem to search for the tomb of Jesus. Helena traveled to Jerusalem on a pilgrimage, where she recognized the site where Jesus was crucified, buried, and raised from the dead. On the spot, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was constructed and dedicated in 335 CE. Helena also claimed to have found the True Cross. Burial remains from the Byzantine period are exclusively Christian, suggesting that the population of Jerusalem in Byzantine times probably consisted only of Christians.[37]

In the 5th century, the eastern continuation of the Roman Empire, ruled from the recently renamed Constantinople, maintained control of the city. Within the span of a few decades, Jerusalem shifted from Byzantine to Persian rule, then back to Roman-Byzantine dominion. Following Sassanid Khosrau II's early 7th century push through Syria, his generals Shahrbaraz and Shahin attacked Jerusalem aided by the Jews of Palaestina Prima, who had risen up against the Byzantines.[39]

In the Siege of Jerusalem of 614, after 21 days of relentless siege warfare, Jerusalem was captured. Byzantine chronicles relate that the Sassanids and Jews slaughtered tens of thousands of Christians in the city, many at the Mamilla Pool,[40][41] and destroyed their monuments and churches, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This episode has been the subject of much debate between historians.[42] The conquered city would remain in Sassanid hands for some fifteen years until the Byzantine emperor Heraclius reconquered it in 629.[43]

Medieval period

Early Muslim period

Rashidun, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates

Jerusalem was one of the Arab Caliphate's first conquests in 638 CE; according to Arab historians of the time, the Rashidun Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab personally went to the city to receive its submission, cleaning out and praying at the Temple Mount in the process. Umar ibn al-Khattab allowed the Jews back into the city and freedom to live and worship after almost three centuries of banishment by the Romans and Byzantines.

Under the early centuries of Muslim rule, especially during the Umayyad (650–750) dynasty, the city prospered. Around 691–692 CE, the Dome of the Rock was built on the Temple Mount. Rather than a mosque, it is a shrine that enshrines the Foundation Stone. The Al-Aqsa Mosque was also built under Umayyad rule during the late 7th or early 8th century on the southern end of the compound, and was associated with a place of the same name mentioned in the Quran as a place visited by Muhammad during his Night Journey. Jerusalem is not mentioned by any of its names in the Quran, and the Qur'an does not mention the exact location of Al-Aqsa Mosque.[44][45] Some scholars contend that the connection between the Al-Aqsa Mosque referenced in the Quran and the Temple Mount in Jerusalem is the result of an Umayyad political agenda that aimed to rival the prestige of the Mecca sanctuary, which was then ruled by their enemy, Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr.[46][47]

The Abbasid period (750–969) is the least documented of the early Muslim period in general. The Temple Mount area was the center of known building activity, with structures damaged in earthquakes being repaired.

Geographers Ibn Hawqal and al-Istakhri (10th century) describe Jerusalem as "the most fertile province of Palestine",[citation needed] while its native son, the geographer al-Muqaddasi (born 946) devoted many pages to its praises in his most famous work, The Best Divisions in the Knowledge of the Climes. Under Muslim rule Jerusalem did not achieve the political or cultural status enjoyed by the capitals Damascus, Baghdad, Cairo etc. Al-Muqaddasi derives his name from the Arabic name for Jerusalem, Bayt al-Muqaddas, which is linguistically equivalent to the Hebrew Beit Ha-Mikdash, the Holy House.

Fatimid period

The early Arab period was also one of religious tolerance.[citation needed] However, in the early 11th century, the Egyptian Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah ordered the destruction of all churches. In 1033, there was another earthquake, severely damaging the Al-Aqsa Mosque. The Fatimid caliph Ali az-Zahir rebuilt and completely renovated the mosque between 1034 and 1036. The number of naves was drastically reduced from fifteen to seven.[48] Az-Zahir built the four arcades of the central hall and aisle, which presently serve as the foundation of the mosque. The central aisle was double the width of the other aisles and had a large gable roof upon which the dome—made of wood—was constructed.[49] Persian geographer, Nasir Khusraw describes the Aqsa Mosque during a visit in 1047:

The Haram Area (Noble Sanctuary) lies in the eastern part of the city; and through the bazaar of this (quarter) you enter the Area by a great and beautiful gateway (Dargah). ... After passing this gateway, you have on the right two great colonnades (Riwaq), each of which has nine-and-twenty marble pillars, whose capitals and bases are of colored marbles, and the joints are set in lead. Above the pillars rise arches, that are constructed, of masonry, without mortar or cement, and each arch is constructed of no more than five or six blocks of stone. These colonnades lead down to near the Maqsurah.[50]

Seljuk period

Under Az-Zahir's successor al-Mustansir Billah, the Fatimid Caliphate entered a period of instability and decline, as factions fought for power in Cairo. In 1071, Jerusalem was captured by the Turkish warlord Atsiz ibn Uvaq, who seized most of Syria and Palestine as part of the expansion of the Seljuk Turks throughout the Middle East. As the Turks were staunch Sunnis, they were opposed not only to the Fatimids, but also to the numerous Shia Muslims, who saw themselves removed from dominance after a century of Fatimid rule. In 1176, riots between Sunnis and Shiites in Jerusalem led to a massacre of the latter. Although the Christians of the city were left unmolested, and allowed access to the Christian holy sites, the wars with Byzantium and the general instability in Syria impeded the arrival pilgrims from Europe. The Seljuks also forbade the repair of any church, despite the damages suffered in the recent turmoils. There does not appear to have been a significant Jewish community in the city at this time.

In 1086, the Seljuk emir of Damascus, Tutush I, appointed Artuk Bey governor of Jerusalem. Artuk died in 1091, and his sons Sökmen and Ilghazi succeeded him. In August 1098, while the Seljuks were distracted by the arrival of the First Crusade in Syria, the Fatimids under vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah appeared before the city and laid siege to it. After six weeks, the Seljuk garrison capitulated and was allowed to leave for Damascus and Diyar Bakr. The Fatimid takeover was followed by the expulsion of most of the Sunnis, in which many of them were also killed.

Crusader/Ayyubid period

The time span consisting of the 12th and 13th centuries is sometimes referred to as the medieval period, or the Middle Ages, in the history of Jerusalem.[51]

First Crusader kingdom (1099–1187)

Fatimid control of Jerusalem ended when it was captured by Crusaders in July 1099. The capture was accompanied by a massacre of almost all of the Muslim and Jewish inhabitants. Jerusalem became the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Godfrey of Bouillon, was elected Lord of Jerusalem on 22 July 1099, but did not assume the royal crown and died a year later.[52] Barons offered the lordship of Jerusalem to Godfrey's brother Baldwin, Count of Edessa, who had himself crowned by the Patriarch Daimbert on Christmas Day 1100 in the basilica of Bethlehem.[52]

Christian settlers from the West set about rebuilding the principal shrines associated with the life of Christ. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was ambitiously rebuilt as a great Romanesque church, and Muslim shrines on the Temple Mount (the Dome of the Rock and the Jami Al-Aqsa) were converted for Christian purposes. It is during this period of Frankish occupation that the Military Orders of the Knights Hospitaller and the Knights Templar have their beginnings. Both grew out of the need to protect and care for the great influx of pilgrims travelling to Jerusalem in the 12th century.

Ayyubid control

The Kingdom of Jerusalem lasted until 1291; however, Jerusalem itself was recaptured by Saladin in 1187 (see Siege of Jerusalem (1187)), who permitted worship of all religions. According to Rabbi Elijah of Chelm, German Jews lived in Jerusalem during the 11th century. The story is told that a German-speaking Jew saved the life of a young German man surnamed Dolberger. Thus when the knights of the First Crusade came to besiege Jerusalem, one of Dolberger's family members rescued Jews in Palestine and carried them back to the German city of Worms to repay the favor.[53] Further evidence of German communities in the holy city comes in the form of halakic questions sent from Germany to Jerusalem during the second half of the 11th century.[54]

In 1173 Benjamin of Tudela visited Jerusalem. He described it as a small city full of Jacobites, Armenians, Greeks, and Georgians. Two hundred Jews dwelt in a corner of the city under the Tower of David. In 1219 the walls of the city were razed by order of al-Mu'azzam, the Ayyubid sultan of Damascus. This rendered Jerusalem defenseless and dealt a heavy blow to the city's status. The Ayyubids destroyed the walls in expectation of ceding the city to the Crusaders as part of a peace treaty. In 1229, by treaty with Egypt's ruler al-Kamil, Jerusalem came into the hands of Frederick II of Germany. In 1239, after a ten-year truce expired, he began to rebuild the walls; these were again demolished by an-Nasir Da'ud, the emir of Kerak, in the same year.

In 1243 Jerusalem came again into the power of the Christians, and the walls were repaired. The Khwarezmian Empire took the city in 1244 and were in turn driven out by the Ayyubids in 1247. In 1260 the Mongols under Hulagu Khan engaged in raids into Palestine. It is unclear if the Mongols were ever in Jerusalem, as it was not seen as a settlement of strategic importance at the time. However, there are reports that some of the Jews that were in Jerusalem temporarily fled to neighboring villages.[citation needed]

Mamluk period

In 1250 a crisis within the Ayyubid state led to the rise of the Mamluks to power and a transition to the Mamluk Sultanate, which is divided between the Bahri and Burji periods. The Ayyubids tried to hold on to power in Syria, but the Mongol invasion of 1260 put an end to this. A Mamluk army defeated the Mongol incursion and in the aftermath Baybars, the true founder of the Mamluk state, emerged as ruler of Egypt, the Levant, and the Hijaz.[55]: 54 The Mamluks ruled over Palestine including Jerusalem from 1260 until 1516.[56] In the decades after 1260 they also worked to eliminate the remaining Crusader states in the region. The last of these was defeated with the capture of Acre in 1291.[55]: 54

Jerusalem was a significant site of Mamluk architectural patronage. The frequent building activity in the city during this period is evidenced by the 90 remaining structures that date from the 13th to 15th centuries.[56] The types of structures built included madrasas, libraries, hospitals, caravanserais, fountains (or sabils), and public baths.[56] Much of the building activity was concentrated around the edges of the Temple Mount or Haram al-Sharif.[56] Old gates to the site lost importance and new gates were built,[56] while significant parts of the northern and western porticos along the edge of the Temple Mount plaza were built or rebuilt in this period.[55] Tankiz, the Mamluk amir in charge of Syria during the reign of al-Nasir Muhammad, built a new market called Suq al-Qattatin (Cotton Market) in 1336–7, along with the gate known as Bab al-Qattanin (Cotton Gate), which gave access to the Temple Mount from this market.[56][55] The late Mamluk sultan al-Ashraf Qaytbay also took interest in the city. He commissioned the building of the Madrasa al-Ashrafiyya, completed in 1482, and the nearby Sabil of Qaytbay, built shortly after in 1482; both were located on the Temple Mount.[56][55] Qaytbay's monuments were the last major Mamluk constructions in the city.[55]: 589–612

Jewish presence

Rabbinical Jewish tradition, based on a source of doubtful authenticity, holds that in 1267, the Jewish Catalan sage Nahmanides travelled to Jerusalem, where he established the synagogue much later named after him,[57] today the second oldest active synagogue in Jerusalem, after that of the Karaite Jews built about 300 years earlier.[dubious – discuss][citation needed] Scholars date the Ramban Synagogue to the 13th century or later.[57]

Latin presence

The first provincial or superior of the Franciscan religious order, founded by Francis of Assisi, was Brother Elia from Assisi. In the year 1219 the founder himself visited the region in order to preach the Gospel to the Muslims, seen as brothers and not enemies. The mission resulted in a meeting with the sultan of Egypt, Malik al-Kamil, who was surprised by his unusual behaviour. The Franciscan Province of the East extended to Cyprus, Syria, Lebanon, and the Holy Land. Before the taking over of Acre (on 18 May 1291), Franciscan friaries were present at Acre, Sidon, Antioch, Tripoli, Jaffa, and Jerusalem.[citation needed]

From Cyprus, where they took refuge at the end of the Latin Kingdom, the Franciscans started planning a return to Jerusalem, given the good political relations between the Christian governments and the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. Around the year 1333 the French friar Roger Guerin succeeded in buying the Cenacle[58] (the room where the Last Supper took place) on Mount Zion and some land to build a monastery nearby for the friars, using funds provided by the king and queen of Naples. With two papal bullae, Gratias Agimus and Nuper Carissimae, dated in Avignon, 21 November 1342, Pope Clement VI approved and created the new entity which would be known as the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land (Custodia Terrae Sanctae).[59][better source needed]

The friars, coming from any of the Order's provinces, under the jurisdiction of the father guardian (superior) of the monastery on Mount Zion, were present in Jerusalem, in the Cenacle, in the church of the Holy Sepulcher, and in the Basilica of the Nativity at Bethlehem. Their principal activity was to ensure liturgical life in these Christian sanctuaries and to give spiritual assistance to the pilgrims coming from the West, to European merchants resident or passing through the main cities of Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon, and to have a direct and authorized relation with the Eastern Christianity Oriental communities.[citation needed]

The monastery on Mount Zion was used by Brother Alberto da Sarteano for his papal mission for the union of the Oriental Christians (Greeks, Copts, and Ethiopians) with Rome during the Council of Florence (1440). For the same reason the party guided by Brother Giovanni di Calabria halted in Jerusalem on his way to meet the Christian Negus of Ethiopia (1482).[citation needed]

In 1482, the visiting Dominican priest Felix Fabri described Jerusalem as "a dwelling place of diverse nations of the world, and is, as it were, a collection of all manner of abominations". As "abominations" he listed Saracens, Greeks, Syrians, Jacobites, Abyssinians, Nestorians, Armenians, Gregorians, Maronites, Turcomans, Bedouins, Assassins, a possible Druze sect, Mamluks, and the Jews, whom he referred to "as the most cursed of all". However, a Christian pilgrim from Bohemia who had visited Jerusalem in 1491–1492 wrote in his book Journey to Jerusalem: "Christians and Jews alike in Jerusalem lived in great poverty and in conditions of great deprivation, there are not many Christians but there are many Jews, and these the Muslims persecute in various ways. Christians and Jews go about in Jerusalem in clothes considered fit only for wandering beggars. The Muslims know that the Jews think and even say that this is the Holy Land which has been promised to them and that those Jews who dwell there are regarded as holy by Jews elsewhere, because, in spite of all the troubles and sorrows inflicted on them by the Muslims, they refuse to leave the Land."[60] Only the Latin Christians "long with all their hearts for Christian princes to come and subject all the country to the authority of the Church of Rome".[61]

Early modern period

Early Ottoman period

In 1516, Jerusalem was taken over by the Ottoman Empire along with all of Greater Syria and enjoyed a period of renewal and peace under Suleiman the Magnificent, including the construction of the walls, which define until today what is now known as the Old City of Jerusalem. The outline of the walls largely follows that of different older fortifications. The rule of Suleiman and subsequent Ottoman Sultans brought an age of "religious peace"; Jew, Christian and Muslim enjoyed freedom of religion and it was possible to find a synagogue, a church and a mosque on the same street. The city remained open to all religions, although the empire's faulty management after Suleiman the Magnificent meant economical stagnation.[citation needed]

Latin presence

In 1551 the Friars were expelled by the Turks[62] from the Cenacle and from their adjoining monastery. However, they were granted permission to purchase a Georgian monastery of nuns in the northwest quarter of the city, which became the new center of the Custody in Jerusalem and developed into the Latin Convent of Saint Saviour (known as Dayr al Ātīn دير الاتين دير اللاتين Arabic)[63]).[64]

Jewish presence

In 1700, Judah HeHasid led the largest organized group of Jewish immigrants to the Land of Israel in centuries. His disciples built the Hurva Synagogue, which served as the main synagogue in Jerusalem from the 18th century until 1948, when it was destroyed by the Arab Legion.[Note 2] The synagogue was rebuilt in 2010.

Local vs. central power

In response to the onerous taxation policies and military campaigns against the city's hinterland by the governor Mehmed Pasha Kurd Bayram, the notables of Jerusalem, allied with the local peasantry and Bedouin, rebelled against the Ottomans in what became known as the Naqib al-Ashraf revolt and took control of the city in 1703–1705 before an imperial army reestablished Ottoman authority there. The consequent loss of power of Jerusalem's al-Wafa'iya al-Husayni family, which led the rebellion, paved the way for the al-Husayni family becoming one of the city's leading families.[66][67] Thousands of Ottoman troops were garrisoned in Jerusalem in the aftermath of the revolt, which caused a decline in the local economy.[68]

Late modern period

Late Ottoman period

In the mid-19th century, with the decline of the Ottoman Empire, the city was a backwater, with a population that did not exceed 8,000.[citation needed] Nevertheless, it was, even then, an extremely heterogeneous city because of its significance to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The population was divided into four major communities – Jewish, Christian, Muslim, and Armenian – and the first three of these could be further divided into countless subgroups, based on precise religious affiliation or country of origin. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was meticulously partitioned between the Greek Orthodox, Catholic, Armenian, Coptic, and Ethiopian churches. Tensions between the groups ran so deep that the keys to the shrine and its doors were safeguarded by a pair of 'neutral' Muslim families.

At the time, the communities were located mainly around their primary shrines. The Muslim community surrounded the Haram ash-Sharif or Temple Mount (northeast), the Christians lived mainly in the vicinity of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (northwest), the Jews lived mostly on the slope above the Western Wall (southeast), and the Armenians lived near the Zion Gate (southwest). In no way was this division exclusive, though it did form the basis of the four quarters during the British Mandate (1917–1948).

Several changes with long-lasting effects on the city occurred in the mid-19th century: their implications can be felt today and lie at the root of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict over Jerusalem. The first of these was a trickle of Jewish immigrants from the Middle East and Eastern Europe. The first such immigrants were Orthodox Jews: some were elderly individuals, who came to die in Jerusalem and be buried on the Mount of Olives; others were students, who came with their families to await the coming of the Messiah, adding new life to the local population. At the same time, European colonial powers began seeking toeholds in the city, hoping to expand their influence pending the imminent collapse of the Ottoman Empire. This was also an age of Christian religious revival, and many churches sent missionaries to proselytize among the Muslim and especially the Jewish populations, believing that this would speed the Second Coming of Christ. Finally, the combination of European colonialism and religious zeal was expressed in a new scientific interest in the biblical lands in general and Jerusalem in particular. Archeological and other expeditions made some spectacular finds, which increased interest in Jerusalem even more.[citation needed]

By the 1860s, the city, with an area of only one square kilometer, was already overcrowded. Thus began the construction of the New City, the part of Jerusalem outside of the city walls. Seeking new areas to stake their claims, the Russian Orthodox Church began constructing a complex, now known as the Russian Compound, a few hundred meters from Jaffa Gate. The first attempt at residential settlement outside the walls of Jerusalem was undertaken by Jews, who built a small complex on the hill overlooking Zion Gate, across the Valley of Hinnom. This settlement, known as Mishkenot Sha'ananim, eventually flourished and set the precedent for other new communities to spring up to the west and north of the Old City. In time, as the communities grew and connected geographically, this became known as the New City.

In 1882, around 150 Jewish families arrived in Jerusalem from Yemen. Initially they were not accepted by the Jews of Jerusalem and lived in destitute conditions supported by the Christians of the Swedish-American colony, who called them Gadites.[69] In 1884, the Yemenites moved into Silwan.

British Mandate period

The British were victorious over the Ottomans in the Middle East during World War I and victory in Palestine was a step towards dismemberment of that empire. General Sir Edmund Allenby, commander-in-chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, entered Jerusalem on foot out of respect for the Holy City, on 11 December 1917.[70]

By the time General Allenby took Jerusalem from the Ottomans in 1917, the new city was a patchwork of neighborhoods and communities, each with a distinct ethnic character. This continued under British rule, as the New City of Jerusalem grew outside the old city walls, and the Old City of Jerusalem gradually emerged as little more than an impoverished older neighborhood. Sir Ronald Storrs, the first British military governor of the city, issued a town planning order requiring new buildings in the city to be faced with sandstone and thus preserving some of the overall look of the city even as it grew.[71] The Pro-Jerusalem Council[72] played an important role in the outlook of the British-ruled city.

The British had to deal with a conflicting demand that was rooted in Ottoman rule. Agreements for the supply of water, electricity, and the construction of a tramway system—all under concessions granted by the Ottoman authorities—had been signed by the city of Jerusalem and a Greek citizen, Euripides Mavromatis, on 27 January 1914. Work under these concessions had not begun and, by the end of the war the British occupying forces refused to recognize their validity. Mavromatis claimed that his concessions overlapped with the Auja Concession that the government had awarded to Rutenberg in 1921 and that he had been deprived of his legal rights. The Mavromatis concession, in effect despite earlier British attempts to abolish it, covered Jerusalem and other localities (e.g., Bethlehem) within a radius of 20 km (12 mi) around the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.[73]

In 1922, the League of Nations at the Conference of Lausanne entrusted the United Kingdom to administer Palestine, neighbouring Transjordan, and Iraq beyond it. From 1922 to 1948 the total population of the city rose from 52,000 to 165,000, comprising two-thirds Jews and one-third Arabs (Muslims and Christians).[74] Relations between Arab Christians and Muslims and the growing Jewish population in Jerusalem deteriorated, resulting in recurring unrest. Jerusalem, in particular, was affected by the 1920 Nebi Musa riots and 1929 Palestine riots. Under the British, new garden suburbs were built in the western and northern parts of the city[75][76] and institutions of higher learning such as the Hebrew University were founded.[77] Two important new institutions, the Hadassah Medical Center and Hebrew University, were founded on Jerusalem's Mount Scopus. The level of violence continued to escalate throughout the 1930s and 1940s. In July 1946 members of the underground Zionist group Irgun blew up a part of the King David Hotel, where the British forces were temporarily located, an act which led to the death of 91 civilians.

On 29 November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly approved a plan which would partition Mandatory Palestine into two states: one Jewish and one Arab. Each state would be composed of three major sections, linked by extraterritorial crossroads, plus an Arab enclave at Jaffa. Expanded Jerusalem would fall under international control as a Corpus Separatum.

-

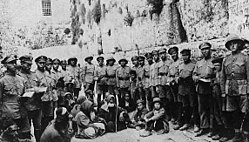

Jewish Legion soldiers at the Western Wall after taking part in 1917 British conquest of Jerusalem

-

Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem during 1944 British demolition of recent construction obscuring the historic city walls

-

Main residential areas of Jerusalem in 1947

-

The Jerusalem boundary in 1947 and the proposed boundary of a Corpus Separatum.

War and partition between Israel and Jordan (1948–1967)

1948 war

After partition, the fight for Jerusalem escalated, with heavy casualties among both fighters and civilians on the British, Jewish, and Arab sides. By the end of March 1948, just before the British withdrawal, and with the British increasingly reluctant to intervene, the roads to Jerusalem were cut off by Arab irregulars, placing the Jewish population of the city under siege. The siege was eventually broken, though massacres of civilians occurred on both sides,[citation needed] before the 1948 Arab–Israeli War began with the end of the British Mandate in May 1948.

The 1948 Arab–Israeli War led to massive displacement of Arab and Jewish populations. According to Benny Morris, due to mob and militia violence on both sides, 1,500 of the 3,500 (mostly ultra-Orthodox) Jews in the Old City evacuated to west Jerusalem as a unit.[78] See also Jewish Quarter. The comparatively populous Arab village of Lifta (today within the bounds of Jerusalem) was captured by Israeli troops in 1948, and its residents were loaded on trucks and taken to East Jerusalem.[78][79][80] The villages of Deir Yassin, Ein Karem and Malcha, as well as neighborhoods to the west of Jerusalem's Old City such as Talbiya, Katamon, Baka, Mamilla and Abu Tor, also came under Israeli control, and their residents were forcibly displaced;[citation needed] in some cases, as documented by Israeli historian Benny Morris and Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi, among others, expulsions and massacres occurred.[78][81]

In May 1948 the US Consul, Thomas C. Wasson, was assassinated outside the YMCA building. Four months later the UN mediator, Count Bernadotte, was also shot dead in the Katamon district of Jerusalem by the Jewish Stern Group.[citation needed]

Division between Jordan and Israel (1948–1967)

The United Nations proposed, in its 1947 plan for the partition of Palestine, for Jerusalem to be a city under international administration. The city was to be completely surrounded by the Arab state, with only a highway to connect international Jerusalem to the Jewish state.

Following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Jerusalem was divided. The Western half of the New City became part of the newly formed state of Israel, while the eastern half, along with the Old City, was occupied by Jordan. According to David Guinn,

Concerning Jewish holy sites, Jordan breached its commitment to appoint a committee to discuss, among other topics, free access of Jews to the holy sites under its jurisdiction, mainly in the Western Wall and the important Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives, as provided in the Article 8.2 of the Cease Fire Agreement between it and Israel dated April 3, 1949. Jordan permitted the paving of new roads in the cemetery, and tombstones were used for paving in Jordanian army camps. The Cave of Shimon the Just became a stable.[82]

According to Gerald M. Steinberg, Jordan ransacked 57 ancient synagogues, libraries and centers of religious study in the Old City Of Jerusalem, 12 were totally and deliberately destroyed. Those that remained standing were defaced, used for housing of both people and animals. Appeals were made to the United Nations and in the international community to declare the Old City to be an 'open city' and stop this destruction, but there was no response.[83] (See also Hurva Synagogue)

On 23 January 1950, the Knesset passed a resolution that stated Jerusalem was the capital of Israel.[citation needed]

State of Israel

East Jerusalem was captured by the Israel Defense Forces on June 7, 1967 during Six-Day War. On June 11, Israel demolished the seven centuries old Moroccan Quarter; along with it, it destroyed 14 religious buildings, including 2 mosques, 135 homes inhabited by 650 people.[84] Thereafter a public plaza was built in its place adjoining the Western Wall. However, the Waqf (Islamic trust) was granted administration of the Temple Mount and thereafter Jewish prayer on the site was prohibited by both Israeli and Waqf authorities.

Most Jews celebrated the event as a liberation of the city; a new Israeli holiday was created, Jerusalem Day (Yom Yerushalayim), and the most popular secular Hebrew song, "Jerusalem of Gold" (Yerushalayim shel zahav), became popular in celebration. Many large state gatherings of the State of Israel take place at the Western Wall today, including the swearing-in of various Israel army officers units, national ceremonies such as memorial services for fallen Israeli soldiers on Yom Hazikaron, huge celebrations on Yom Ha'atzmaut (Israel Independence Day), huge gatherings of tens of thousands on Jewish religious holidays, and ongoing daily prayers by regular attendees. The Western Wall has become a major tourist destination spot.

Under Israeli control, members of all religions are largely granted access to their holy sites. The major exceptions being security limitations placed on some Arabs from the West Bank and Gaza Strip from accessing holy sites due to their inadmissibility to Jerusalem, as well as limitations on Jews from visiting the Temple Mount due to both politically motivated restrictions (where they are allowed to walk on the Mount in small groups, but are forbidden to pray or study while there) and religious edicts that forbid Jews from trespassing on what may be the site of the Holy of the Holies. Concerns have been raised about possible attacks on the al-Aqsa Mosque after a serious arson attack on the mosque in 1969 (started by Denis Michael Rohan, an Australian fundamentalist Christian found by the court to be insane). Riots broke out following the opening of an exit in the Arab Quarter for the Western Wall Tunnel on the instructions of the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, which prior Prime Minister Shimon Peres had instructed to be put on hold for the sake of peace (stating "it has waited for over 1000 years, it could wait a few more").

Conversely, Israeli and other Jews have showed concerns over excavations being done by the Waqf on the Temple Mount that could harm Temple relics, particularly excavations to the north of Solomon's Stables that were designed to create an emergency exit for them (having been pressured to do so by Israeli authorities).[85] Some Jewish sources allege that the Waqf's excavations in Solomon's Stables also seriously harmed the Southern Wall; however an earthquake in 2004 that damaged the eastern wall could also be to blame.

The status of East Jerusalem remains a highly controversial issue. The international community does not recognize the annexation of the eastern part of the city, and most countries maintain their embassies in Tel Aviv. In May 2018 The United States and Guatemala moved the embassies to Jerusalem.[86] The United Nations Security Council Resolution 478 declared that the Knesset's 1980 "Jerusalem Law" declaring Jerusalem as Israel's "eternal and indivisible" capital was "null and void and must be rescinded forthwith". This resolution advised member states to withdraw their diplomatic representation from the city as a punitive measure. The council has also condemned Israeli settlement in territories captured in 1967, including East Jerusalem (see UNSCR 452, 465 and 741).

Since Israel gained control over East Jerusalem in 1967, Jewish settler organizations have sought to establish a Jewish presence in neighborhoods such as Silwan.[87][88] In the 1980s, Haaretz reports, the Housing Ministry "then under Ariel Sharon, worked hard to seize control of property in the Old City and in the adjacent neighborhood of Silwan by declaring them absentee property. The suspicion arose that some of the transactions were not legal; an examination committee ... found numerous flaws." In particular, affidavits claiming that Arab homes in the area were absentee properties, filed by Jewish organizations, were accepted by the Custodian without any site visits or other follow-up on the claims.[89] ElAd, a settlement organization[90][91][92][93] which Haaretz says promotes the "Judaization" of East Jerusalem,[94] and the Ateret Cohanim organization, are working to increase Jewish settlement in Silwan in cooperation with the Committee for the Renewal of the Yemenite Village in Shiloah.[95]

See Jewish Quarter (Jerusalem).

Historiography

Given the city's central position in Israeli nationalism and Palestinian nationalism, the selectivity required to summarize 5,000 years of inhabited history is often influenced by ideological bias or background.[96] For example, the Jewish periods of the city's history are important to Israeli nationalists, whose discourse states that modern Jews originate and descend from the Israelites,[Note 3][Note 4] while the Islamic periods of the city's history are important to Palestinian nationalists, whose discourse suggests that modern Palestinians descend from all the different peoples who have lived in the region.[Note 5][Note 6] As a result, both sides claim the history of the city has been politicized by the other in order to strengthen their relative claims to the city,[96][101][102] and that this is borne out by the different focuses the different writers place on the various events and eras in the city's history.

Graphical overview of Jerusalem's historical periods (by rulers)

See also

References

Notes

- ^ "When Judea was converted into a Roman province in 6 CE, Jerusalem ceased to be the administrative capital of the country. The Romans moved the governmental residence and military headquarters to Caesarea. The centre of government was thus removed from Jerusalem, and the administration became increasingly based on inhabitants of the Hellenistic cities (Sebaste, Caesarea and others)."[21]

- ^ "This was not done in the heat of battle, but by official order. Explosives were placed carefully and thoughtfully under the springing points of the domes, of the great Hurva synagogue."[65]

- ^ "No city in the world, not even Athens or Rome, ever played as great a role in the life of a nation for so long a time, as Jerusalem has done in the life of the Jewish people."[97]

- ^ "For three thousand years, Jerusalem has been the center of Jewish hope and longing. No other city has played such a dominant role in the history, culture, religion and consciousness of a people as has Jerusalem in the life of Jewry and Judaism. Throughout centuries of exile, Jerusalem remained alive in the hearts of Jews everywhere as the focal point of Jewish history, the symbol of ancient glory, spiritual fulfillment and modern renewal. This heart and soul of the Jewish people engenders the thought that if you want one simple word to symbolize all of Jewish history, that word would be 'Jerusalem.'"[98]

- ^ "Throughout history a great diversity of peoples has moved into the region and made Palestine their homeland: Canaanites, Jebusites, Philistines from Crete, Anatolian and Lydian Greeks, Hebrews, Amorites, Edomites, Nabateans, Arameans, Romans, Arabs, and European crusaders, to name a few. Each of them appropriated different regions that overlapped in time and competed for sovereignty and land. Others, such as Ancient Egyptians, Hittites, Persians, Babylonians, and Mongols, were historical 'events' whose successive occupations were as ravaging as the effects of major earthquakes ... Like shooting stars, the various cultures shine for a brief moment before they fade out of official historical and cultural records of Palestine. The people, however, survive. In their customs and manners, fossils of these ancient civilizations survived until modernity – albeit modernity camouflaged under the veneer of Islam and Arabic culture."[99]

- ^ "(With reference to Palestinians in Ottoman times) Although proud of their Arab heritage and ancestry, the Palestinians considered themselves to be descended not only from Arab conquerors of the 7th century but also from indigenous peoples who had lived in the country since time immemorial, including the ancient Hebrews and the Canaanites before them. Acutely aware of the distinctiveness of Palestinian history, the Palestinians saw themselves as the heirs of its rich associations."[100]

Citations

- ^ a b Slavik, Diane. 2001. Cities through Time: Daily Life in Ancient and Modern Jerusalem. Geneva, Illinois: Runestone Press, p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8225-3218-7

- ^ Mazar, Benjamin. 1975. The Mountain of the Lord. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., p. 45. ISBN 0-385-04843-2

- ^ "'Massive' ancient wall uncovered in Jerusalem". CNN. 7 September 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, Princeton University Press, 1992 pp. 268, 270.

- ^ 2 Samuel 24:23, which literally has "Araunah the King gave to the King [David]".

- ^ Biblical Archaeology Review, Reading David in Genesis, Gary A. Rendsburg.

- ^ Peake's Commentary on the Bible.

- ^ Rainbow, Jesse. "From Creation to Babel: Studies in Genesis 1–11" (PDF). RBL. Retrieved 22 April 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Asaf Shtull-Trauring (6 May 2011). "The Keys to the Kingdom". Haaretz.

- ^ Amihai Mazar (2010). "Archaeology and the Biblical Narrative: The Case of the United Monarchy". In Reinhard G. Kratz and Hermann Spieckermann (ed.). One God, One Cult, One Nation (PDF). De Gruyter. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2010.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein (2010). "A Great United Monarchy?". In Reinhard G. Kratz and Hermann Spieckermann (ed.). One God, One Cult, One Nation (PDF). De Gruyter. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2013.

- ^ a b Israel Finkelstein & Neil Asher Silberman (2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-2338-6.

- ^ Thompson, Thomas L., 1999, The Bible in History: How Writers Create a Past, Jonathan Cape, London, ISBN 978-0-224-03977-2 p. 207

- ^ Sergi, Omer (2023). The Two Houses of Israel: State Formation and the Origins of Pan-Israelite Identity. SBL Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-1-62837-345-5.

- ^ Albright, William (1963). The Biblical Period from Abraham to Ezra: An Historical Survey. Harpercollins College Div. ISBN 0-06-130102-7.

- ^ Jan Assmann: Martyrium, Gewalt, Unsterblichkeit. Die Ursprünge eines religiösen Syndroms. In: Jan-Heiner Tück (Hrsg.): Sterben für Gott – Töten für Gott? Religion, Martyrium und Gewalt. [Deutsch]. Herder Verlag, Freiburg i. Br. 2015, 122–147, hier: S. 136.

- ^ Morkholm 2008, p. 290.

- ^ "John Hyrcanus II". www.britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. 18 March 2024.

- ^ Feissel, Denis (23 December 2010). Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae: Volume 1 1/1: Jerusalem, Part 1: 1-704. Hannah M. Cotton, Werner Eck, Marfa Heimbach, Benjamin Isaac, Alla Kushnir-Stein, Haggai Misgav. Berlin: De Gruyter. p. 41. ISBN 978-3-11-174100-0. OCLC 840438627.

- ^ Kasher, Aryeh. King Herod: a persecuted persecutor: a case study in psychohistory and psychobiography, Walter de Gruyter, 2007, p. 229. ISBN 3-11-018964-X

- ^ A History of the Jewish People, ed. by H. H. Ben-Sasson, 1976, p. 247.

- ^ McGing, Brian (2002). "Population and Proselytism: How many Jews were there in the ancient world?". Jews in the Hellenistic and Roman cities. John R. Bartlett. London: Routledge. pp. 88–95. ISBN 978-0-203-44634-8. OCLC 52847163.

- ^ Weksler-Bdolah, Shlomit (2019). Aelia Capitolina – Jerusalem in the Roman period: in light of archaeological research. BRILL. p. 3. ISBN 978-90-04-41707-6. OCLC 1170143447.

The historical description is consistent with the archeological finds. Collapses of massive stones from the walls of the Temple Mount were exposed lying over the Herodian street running along the Western Wall of the Temple Mount. The residential buildings of the Ophel and the Upper City were destroyed by great fire. The large urban drainage channel and the Pool of Siloam in the Lower City silted up and ceased to function, and in many places the city walls collapsed. [...] Following the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 CE, a new era began in the city's history. The Herodian city was destroyed and a military camp of the Tenth Roman Legion established on part of the ruins. In around 130 CE, the Roman emperor Hadrian founded a new city in place of Herodian Jerusalem next to the military camp. He honored the city with the status of a colony and named it Aelia Capitolina and possibly also forbidding Jews from entering its boundaries

- ^ Westwood, Ursula (1 April 2017). "A History of the Jewish War, AD 66–74". Journal of Jewish Studies. 68 (1): 189–193. doi:10.18647/3311/jjs-2017. ISSN 0022-2097.

- ^ Ben-Ami, Doron; Tchekhanovets, Yana (2011). "The Lower City of Jerusalem on the Eve of Its Destruction, 70 CE: A View From Hanyon Givati". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 364: 61–85. doi:10.5615/bullamerschoorie.364.0061. ISSN 0003-097X. S2CID 164199980.

- ^ Maclean Rogers, Guy (2021). For the Freedom of Zion: The Great Revolt of Jews against Romans, 66–74 CE. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-300-26256-8. OCLC 1294393934.

- ^ Peter Schäfer (2003). The Bar Kokhba war reconsidered: new perspectives on the second Jewish revolt against Rome. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-3-16-148076-8. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Lehmann, Clayton Miles (22 February 2007). "Palestine: History". The On-line Encyclopedia of the Roman Provinces. The University of South Dakota. Archived from the original on 10 March 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

- ^ Cohen, Shaye J. D. (1996). "Judaism to Mishnah: 135–220 AD". In Hershel Shanks (ed.). Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism: A Parallel History of their Origins and Early Development. Washington DC: Biblical Archaeology Society. p. 196.

- ^ Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah (2019). Aelia Capitolina – Jerusalem in the Roman Period: In Light of Archaeological Research. Brill. pp. 54–58. ISBN 978-90-04-41707-6.

- ^ Jacobson, David. "The Enigma of the Name Īliyā (= Aelia) for Jerusalem in Early Islam". Revision 4. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred, eds. (2007). "Bar Kokhba". Encyclopaedia Judaica. Quoting from Gibson, Shimon. Encyclopaedia Hebraica (2 ed.). Vol. 3 (2 ed.). Thomson Gale. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-02-865931-2.

- ^ Bar, Doron (2005). "Rural Monasticism as a Key Element in the Christianization of Byzantine Palestine". The Harvard Theological Review. 98 (1): 49–65. doi:10.1017/S0017816005000854. ISSN 0017-8160. JSTOR 4125284. S2CID 162644246.

The phenomenon was most prominent in Judea, and can be explained by the demographic changes that this region underwent after the second Jewish revolt of 132-135 C.E. The expulsion of Jews from the area of Jerusalem following the suppression of the revolt, in combination with the penetration of pagan populations into the same region, created the conditions for the diffusion of Christians into that area during the fifth and sixth centuries. [...] This regional population, originally pagan and during the Byzantine period gradually adopting Christianity, was one of the main reasons that the monks chose to settle there. They erected their monasteries near local villages that during this period reached their climax in size and wealth, thus providing fertile ground for the planting of new ideas.

- ^ H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, page 334: "Jews were forbidden to live in the city and were allowed to visit it only once a year, on the Ninth of Ab, to mourn on the ruins of their holy Temple."

- ^ Virgilio Corbo, The Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem (1981)

- ^ Zissu, Boaz [in Hebrew]; Klein, Eitan (2011). "A Rock-Cut Burial Cave from the Roman Period at Beit Nattif, Judaean Foothills" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 61 (2): 196–216. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ Gideon Avni, The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach, p. 144, at Google Books, Oxford University Press 2014 p. 144.

- ^ Beckles Willson, Rachel (2013). Orientalism and Musical Mission: Palestine and the West. Cambridge University Press. p. 146. ISBN 9781107036567.

- ^ Conybeare, Frederick C. (1910). The Capture of Jerusalem by the Persians in 614 AD. English Historical Review 25. pp. 502–17.

- ^ Hidden Treasures in Jerusalem Archived 6 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, the Jerusalem Tourism Authority

- ^ Jerusalem blessed, Jerusalem cursed: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the Holy City from David's time to our own. By Thomas A. Idinopulos, I.R. Dee, 1991, p. 152

- ^ Horowitz, Elliot. "Modern Historians and the Persian Conquest of Jerusalem in 614". Jewish Social Studies. Archived from the original on 26 May 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ Rodney Aist, The Christian Topography of Early Islamic Jerusalem, Brepols Publishers, 2009 p. 56: 'Persian control of Jerusalem lasted from 614 to 629'.

- ^ el-Khatib, Abdallah (1 May 2001). "Jerusalem in the Qur'ān". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 28 (1): 25–53. doi:10.1080/13530190120034549. ISSN 1353-0194. S2CID 159680405. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ^ Khalek, N. (2011). Jerusalem in Medieval Islamic Tradition. Religion Compass, 5(10), 624–630. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2011.00305.x. "One of the most pressing issues in both medieval and contemporary scholarship related to Jerusalem is weather the city is explicitly referenced in the text of the Qur'an. Sura 17, verse 1, which reads [...] has been variously interpreted as referring to the miraculous Night Journey and Ascension of Muhammad, events recorded in medieval sources and known as the isra and miraj. As we will see, this association is a rather late and even a contested one. [...] The earliest Muslim work on the Religious Merits of Jerusalem was the Fada'il Bayt al-Maqdis by al-Walid ibn Hammad al-Ramli (d. 912 CE), a text which is recoverable from later works. [...] He relates the significance of Jerusalem vis-a-vis the Jewish Temple, conflating 'a collage of biblical narratives' and comments pilgrimage to Jerusalem, a practice which was controversial in later Muslim periods."

- ^ "Miʿrād̲j̲". The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. 7 (New ed. 2006 ed.). Brill. 2006. pp. 97–105.

For this verse, tradition gives three interpretations: The oldest one, which disappears from the more recent commentaries, detects an allusion to Muhammad's Ascension to Heaven. This explanation interprets the expression al-masjid al-aksa, "the further place of worship" in the sense of "Heaven" and, in fact, in the older tradition isra is often used as synonymous with miradj (see Isl., vi, 14). The second explanation, the only one given in all the more modern commentaries, interprets masjid al-aksa as "Jerusalem" and this for no very apparent reason. It seems to have been an Umayyad device intended to further the glorification of Jerusalem as against that of the holy territory (cf. Goldziher, Muh. Stud., ii, 55-6; Isl, vi, 13 ff), then ruled by Abd Allah b. al-Zubayr. Al-Tabarl seems to reject it. He does not mention it in his History and seems rather to adopt the first explanation.

- ^ Silverman, Jonathan (6 May 2005). "The opposite of holiness". Ynetnews. Archived from the original on 12 September 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ^ Ma'oz, Moshe and Nusseibeh, Sari. (2000). Jerusalem: Points of Friction, and Beyond Brill. pp. 136–38. ISBN 90-411-8843-6.

- ^ Elad, Amikam. (1995). Medieval Jerusalem and Islamic Worship Holy Places, Ceremonies, Pilgrimage Brill, pp. 29–43. ISBN 90-04-10010-5.

- ^ "The travels of Nasir-i-Khusrau to Jerusalem, 1047 C.E." Homepages.luc.edu. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ^ Weksler-Bdolah, Shlomit (2011). "Early Islamic and Medieval City Walls of Jerusalem in Light of New Discoveries". In Galor, Katharina; Avni, Gideon (eds.). Unearthing Jerusalem: 150 Years of Archaeological Research in the Holy City. Eisenbrauns. p. 417. Retrieved 7 January 2018 – via Offprint posted at academia.edu.

- ^ a b Bréhier, Louis Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099–1291) Catholic Encyclopedia 1910, accessed 11 March 2008

- ^ Seder ha-Dorot, 1878, p. 252.

- ^ Epstein, in Monatsschrift, vol. xlvii, p. 344; Jerusalem: Under the Arabs.

- ^ a b c d e f Burgoyne, Michael Hamilton (1987). Mamluk Jerusalem: An Architectural Study. British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem by World of Islam Festival Trust. ISBN 9780905035338.

- ^ a b c d e f g M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Jerusalem". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b Roth, Norman (2014). "Synagogues". In Roth, Norman (ed.). Medieval Jewish Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 622. ISBN 978-1-136-77155-2. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ "cenacle - definition of cenacle by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia". Thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ "Custodia Terræ Sanctæ". Custodia.org. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ "The Palestinian – Israel Conflict » Felix Fabri". Zionismontheweb.org. 9 September 2008. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ A. Stewart, Palestine Pilgrims Text Society, Vol. 9–10, pp. 384–91

- ^ "Holy Land Custody". Fmc-terrasanta.org. 30 November 1992. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ Role of Franciscans

- ^ "The Custody". Custodia.org. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ Moshe Safdie (1989) Jerusalem: the Future of the Past, Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 9780395353752. p. 62.

- ^ Manna, Adel (1994). "Eighteenth and Nineteenth-Century Rebellions in Palestine". Journal of Palestine Studies. 25 (1): 53–54. doi:10.1525/jps.1994.24.1.00p0048u.

- ^ Pappe, Ilan (2010). "Prologue". The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty: The Husaynis 1700–1948. Saqi Books. ISBN 9780863568015.

- ^ Ze'evi, Dror (1996). Ab Ottoman Century: The District of Jerusalem in the 1600s. State University of New York Press. p. 84. ISBN 9781438424750.

- ^ Tudor Parfitt (1997). The road to redemption: the Jews of the Yemen, 1900–1950. Brill's series in Jewish Studies, vol 17. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 53.

- ^ Fromkin, David (1 September 2001). A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East (2nd reprinted ed.). Owl Books e. pp. 312–13. ISBN 0-8050-6884-8.

- ^ Amos Elon, "Jerusalem: City of Mirrors". New York: Little, Brown 1989.

- ^ Rapaport, Raquel (2007). "The City of the Great Singer: C. R. Ashbee's Jerusalem". Architectural History. 50. Cambridge University Press: 171-210 [see footnote 37 available online]. doi:10.1017/S0066622X00002926. S2CID 195011405.

- ^ Shamir, Ronen (2013) Current Flow: The Electrification of Palestine. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- ^ "Chart of the population of Jerusalem". Focusonjerusalem.com. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ Tamari, Salim (1999). "Jerusalem 1948: The Phantom City". Jerusalem Quarterly File (3). Archived from the original (Reprint) on 9 September 2006. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- ^ Eisenstadt, David (26 August 2002). "The British Mandate". Jerusalem: Life Throughout the Ages in a Holy City. Bar-Ilan University Ingeborg Rennert Center for Jerusalem Studies. Archived from the original on 16 December 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ^ "History". The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- ^ a b c Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949, Revisited, Cambridge, 2004

- ^ Krystall, Nathan. "The De-Arabization of West Jerusalem 1947–50", Journal of Palestine Studies (27), Winter 1998

- ^ Al-Khalidi, Walid (ed.), All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948, (Washington DC: 1992), "Lifta", pp. 300–03

- ^ Al-Khalidi, Walid (ed.), All that remains: the Palestinian villages occupied and depopulated by Israel in 1948, (Washington DC: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992)

- ^ Protecting Jerusalem's Holy Sites: A Strategy for Negotiating a Sacred Peace by David E. Guinn (Cambridge University Press, 2006) p.35 ISBN 0-521-86662-6

- ^ Jerusalem – 1948, 1967, 2000: Setting the Record Straight by Gerald M. Steinberg (Bar-Ilan University)

- ^ Anwar Abu Eisheh. Sacred Space in Israel and Palestine:Religion and Politics. Taylor & Francis. p. 78.

- ^ Temple Mount destruction stirred archaeologist to action, 8 February 2005 | by Michael McCormack, Baptist Press "Temple Mount destruction stirred archaeologist to action - Baptist Press". Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ Turner, Ashley (17 May 2018). "After US embassy makes controversial move to Jerusalem, more countries follow its lead". CNBC.

- ^ "Letter dated October 16, 1987, from the Permanent Representative of Jordan to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General"[permanent dead link] UN General Assembly Security Council

- ^ "Elad in Silwan: Settlers, Archaeologists and Dispossession". mathaba.net. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012.

- ^ Meron Rapoport.Land lords Archived 20 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine; Haaretz, 20 January 2005

- ^ Yigal Bronner. "Archaeologists for hire: A Jewish settler organisation is using archaeology to further its political agenda and oust Palestinians from their homes"; The Guardian, 1 May 2008

- ^ Ori Kashti and Meron Rapoport."Settler group refuses to vacate land slated for school for the disabled" Archived 5 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine; Haaretz, 15 January 2008

- ^ "The Other Israel: America-Israel Council for Israeli-Palestinian Peace newsletter". Archived from the original on 8 July 2008.

- ^ Seth Freedman (26 February 2008). "Digging into trouble". The Guardian.

- ^ "Group 'Judaizing' East Jerusalem accused of withholding donation sources". Haaretz. 21 November 2007. Archived from the original on 4 January 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- ^ "11 Jewish families move into J'lem neighborhood of Silwan". Haaretz. 1 April 2004. Archived from the original on 16 September 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- ^ a b Azmi Bishara. "A brief note on Jerusalem". Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ David Ben-Gurion, 1947

- ^ Teddy Kollek (1990). Jerusalem. Policy Papers. Vol. 22. Washington, D.C.: Washington Institute For Near East Policy. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9780944029077.

- ^ Ali Qleibo, Palestinian anthropologist

- ^ Walid Khalidi, 1984, Before Their Diaspora: A Photographic History of the Palestinians, 1876–1948. Institute for Palestine Studies

- ^ Eric H. Cline. "How Jews and Arabs Use (and Misuse) the History of Jerusalem to Score Points". Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ Eli E. Hertz. "One Nation's Capital Throughout History" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 January 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

Sources

- Armstrong, Karen (1996). Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths. Random House. ISBN 0-679-43596-4.

- Morkholm, Otto (2008). "Antiochus IV". In William David Davies; Louis Finkelstein (eds.). The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 2, The Hellenistic Age. Cambridge University Press. pp. 278–291. ISBN 978-0-521-21929-7.

Further reading

- Avci, Yasemin, Vincent Lemire, and Falestin Naili. "Publishing Jerusalem's ottoman municipal archives (1892-1917): a turning point for the city's historiography." Jerusalem Quarterly 60 (2014): 110+. online

- Bieberstein, Klaus; Bloedhorn, Hanswulf (1994). Jerusalem. Grundzüge der Baugeschichte vom Chalkolithikum bis zur Frühzeit der osmanischen Herrschaft [Jerusalem. Outline of the architectural history from the Chalcolithic to the early period of Ottoman rule]. 3 volumes. Wiesbaden: Ludwig Reichert, ISBN 3-88226-671-6 (with catalogue of archaeological findspots).