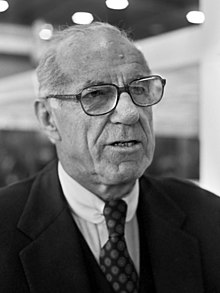

Allan Rosenberg (spy)

Allan Robert Rosenberg (April 21, 1909 – April 1, 1991) was a 20th-century American labor lawyer and civil servant, accused as a Soviet spy by Elizabeth Bentley and listed under Party name "Roy, code names "Roza" in the VENONA Papers and code name "Sid" in the Vasilliev Papers; he also defended Dr. Benjamin Spock ("Dr. Spock").[1][2][3]

Background

[edit]Allan R. Rosenberg was born on April 21, 1909, in Dorchester, Massachusetts. In 1926, he graduated president of his class from Boston Latin School. In 1930, he graduated from Harvard College. In 1936, he graduated from Harvard Law.[3]

Career

[edit]Government service

[edit]

Rosenberg associated with members of the Ware Group of Soviet spies, set up by Harold Ware. Upon Ware's unexpected death in 1935, Nathan Witt succeeded him, while Whittaker Chambers oversaw the group and couriered Government documents it obtained from Washington to New York.[4][5] In 1936, Rosenberg was working "as an unpaid volunteer" for the La Follette Civil Liberties Committee, in fact a subcommittee of the U.S. Senate Committee on Education and Labor (where Ware Group member John Abt worked); Charles Kramer and Charles Flato (another "secret communist") would join them there.[6][7][8] Witt placed Rosenberg in charge of a group of six to eight attorneys during a Congressional investigation into the questionable activities of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) in 1938 and 1939.[citation needed] At the NLRB, Rosenberg "helped litigate charges of union-busting against Republic Steel, and he want to Harlan County, Ky., to investigate abuses in towns controlled by coal companies.[3]

In 1937, he transferred briefly to the Railroad Retirement Board and then in April 1937 joined the National Labor Relations Board through 1941 at the suggestion of Max Lowenthal.[3][9] There, Charles Kramer joined him the following year.

In 1941, Rosenberg transferred from the NLRB to the Board of Economic Warfare (or Office of Economic Warfare).[6][3] "A couple of years later," he joined the Foreign Economic Administration (FEA).[6]

Rosenberg became a member of the Perlo group of Soviet spies during World War II.[citation needed] (Perlo had been a member of the Ware Group earlier.) In November 1943, Earl Browder turned control of the Perlo Group over to Jacob Golos two months before his death; it subsequently was taken over by Elizabeth Bentley.[citation needed]

While employed as the Chief of the Economic Institution Staff for the Foreign Economic Administration, Rosenberg allegedly supplied the Soviet Union with voluminous observations, recommendations, plans and proposals made by various government officials concerning the handling of postwar Germany. He also worked on the Board of Economic Warfare since 1941. Rosenberg's name appears in clear text in a December 1944 Venona decrypt as the source of a State Department memo. Rosenberg appears in the Venona project under his real name.[citation needed]

Private practice

[edit]

After World War II, Rosenberg left government service and went into private practice. He opened a law firm in Washington, DC.[3]

On July 9, 1947, US Representative George Anthony Dondero included Rosenberg when publicly questioneing the "fitness" of United States Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson for failing to ferret out Communist infiltrators in his department. The cause for concern arose from what Dondero called Patterson's lack of ability to "fathom the wiles of the international Communist conspiracy" and to counteract them with "competent personnel." Dondero cited ten government personnel in the War Department who had Communist backgrounds or leanings:

- Colonel Bernard Bernstein

- Russel A. Nixon

- Abraham L. Pomerantz

- Josiah E. DuBois Jr.

- Richard Sasuly

- George Shaw Wheeler

- Heinz Norden

- Max Lowenthal

- Allan Rosenberg (member of Lowenthal's staff)

Dondero stated, "It is with considerable regret that I am forced to the conclusion the Secretary Patterson falls short of these standards."[10]

In June 1948, after the 1947 conviction of Carl Marzani for false and fraudulent statements Rosenberg represented Marzani in appeal, with Arthur Garfield Hays pro hac vice plus Charles E. Ford and Warren L. Sharfman, while Belford V. Lawson Jr. filed a brief on behalf of the National Lawyers Guild and Joseph Forerfiled a brief on behalf of the Civil Rights Congress as amicus curiae urging reversal.[11]

In 1949, Rosenberg joined the firm of Putnam, Bell & Russell, where he became a partner.[3]

In April 1951, Rosenberg argued for the complainant Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee in Anti-Fascist Committee v. McGrath before the U.S. Supreme Court.[12]

On June 23, 1952, and again on February 21, 1956, Rosenberg testified in Congress before HUAC. Counsel in 1952 was David Scribner, counsel in 1956 Benjamin Loring Young.[9][6][13]

In January 1969, Rosenberg represented Dr. Benjamin Spock.[3] In 1962, Spock had joined The Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, otherwise known as SANE. Spock was politically outspoken and active in the movement to end the Vietnam War. In 1968, he and four others (William Sloane Coffin, Marcus Raskin, Mitchell Goodman, and Michael Ferber) were singled out for prosecution by US Attorney General Ramsey Clark on charges of conspiracy to counsel, aid, and abet resistance to the draft.[14] Spock and three of his alleged co-conspirators were convicted, although the five had never been in the same room together. His two-year prison sentence was never served; the case was appealed and in 1969 a federal court set aside his conviction. Spock's legal team included Leonard Boudin with Victor Rabinowitz of Rabinowitz, Boudin & Standard (New York City) and Allan R. Rosenberg of Putnam, Bell & Russell (Boston).[15]

In March 1969, Rosenberg wrote a letter to the U.S. Senate in which he upheld the reputation of Henry S. Kahn MD of Harvard Medical School in the Commissioned Corps of the Public Health Service.[16]

For Putnam, Bell & Russell, Rosenberg represented the United Electrical Workers union in New England, as well as the New England Subaru Dealers Council. He also counseled "hundreds of workers" in front of the Massachusetts Industrial Accident Board.[3]

In 1987, Rosenberg had been living in Boston when he retired from the firm that year.[3]

Personal life and death

[edit]Rosenberg married Erna Rothschild; they had two sons and two daughters.[3]

Rosenberg was a friend of Charles Kramer (the only member of the Ware Group known to continue on into the Perlo Group). Rosenberg was also an amateur photographer with a dark room in his home.[17]

In 1937, Rosenberg joined the National Lawyers Guild, where he remained a member as a late as 1956 during his second appearance before HUAC).[6]

Allan R. Rosenberg died age 81 on April 1, 1991, at his home in West Newton, Massachusetts, following surgery on a brain tumor.[3]

Legacy

[edit]Rosenberg's name appears without cover in Venona but with a cryptonym in the Gorsky Memo.[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Haynes, John Earl (April 2009). "Cover Name, Cryptonym, Pseudonym, and Real Name Index: A Research Historian's Working Reference". Washington: John Earl Haynes. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Vassiliev, Alexander. "Black Notebook" (PDF). Wilson Center. p. 78. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Allan R. Rosenberg, 81: Labor lawyer in capital, Boston". Boston Globe. 4 April 1994. p. 55.

- ^ Chambers, Whittaker (May 1952). Witness. New York: Random House. pp. 799 (total). ISBN 9780895269157. LCCN 52005149.

- ^ Berle, Adolf A. (2 September 1938). "Berle Notes". Washington: John Earl Haynes. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Hearings". Washington: US GPO. 1956. pp. 3252 (Joseph Robison), 3288–3289 (David Rein), 3300–3307 (Rosenberg), 3318 (Ruth Weyand Perry), 3320 (Weyand), 3325 (Weyand), 3329 (Weyand), 3362 (Jacob Krug). Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Cashman, Sean Dennis (1998). America Ascendant: From Theodore Roosevelt to FDR in the Century of American Power, 1901-1945. New York: NYU Press. p. 332. ISBN 9780814715666. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Haynes, John Earl; Klehr, Harvey; Igorevich, Fridrikh (1996). The Secret World of American Communism. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 98. ISBN 0300068557. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ a b Hearings of the United States Congress - House Committee on Un-American Activities. US GPO. 1952. p. 3435. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ "Ex-Army Men Hit as 'Red' Backers" (PDF). The New York Times. 10 July 1947. p. 13.

- ^ "Marzani v. United States, 168 F.2d 133 (D.C. Cir. 1948)". Justia US Law. 21 June 1948. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- ^ "Anti-Fascist Committee v. McGrath". Washington: Find Law. 30 April 1951. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Haynes, John Earl (2000). Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 117, 118, 119, 363, 399, 409 (fn5) (testimony), 422 (fn29). Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ The William Sloane Coffin, Jr. Project Committee. "Once to Every Man and Nation". Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ See United States v. Spock, 416 F.2d 165 (1st Cir. 1969).

- ^ Rosenberg, Allan R. (1972). Hearings Regarding the Administration of the Subversive Activities Control Act of 1950. US GPO. pp. 6022–6024. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ Haynes, John Earl; Klehr, Harvey; Vasilliev, Alexander (2009). Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 276 (friendship), 284 (appearances). ISBN 9780300155723. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Haynes, John Earl (27 October 2005). "Russian Archival Identification of Real Names Behind Cover Names in VENONA". Washington: John Earl Haynes. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

External links

[edit]- Vassiliev, Alexander (2003), Alexander Vassiliev's Notes on Anatoly Gorsky's December 1948 Memo on Compromised American Sources and Networks, retrieved 2012-04-21

- Anti-Fascist Committee v. McGrath (1951) Allan R. Rosenberg argued the cause before the U.S. Supreme Court.

- 2 Lawyers Balk at Query on Red Cell Affiliations: Accused by Herbert Fuchs, Ex-NLRB Employees Use 5th Amendment at House Probe 21 February 1956