Richard Rodgers

Richard Rodgers | |

|---|---|

Rodgers at the St. James Theatre in 1948 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Richard Charles Rodgers |

| Born | June 28, 1902 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | December 30, 1979 (aged 77) New York City, U.S. |

| Genres | Musical theater |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1919–1979 |

| Education | Columbia University (BA) Juilliard School |

Richard Charles Rodgers (June 28, 1902 – December 30, 1979) was an American composer who worked primarily in musical theater. With 43 Broadway musicals and over 900 songs to his credit, Rodgers was one of the most well-known American composers of the 20th century, and his compositions had a significant influence on popular music.

Rodgers is known for his songwriting partnerships, first with lyricist Lorenz Hart and then with Oscar Hammerstein II. With Hart he wrote musicals throughout the 1920s and 1930s, including Pal Joey, A Connecticut Yankee, On Your Toes and Babes in Arms. With Hammerstein he wrote musicals through the 1940s and 1950s, such as Oklahoma!, Flower Drum Song, Carousel, South Pacific, The King and I, and The Sound of Music. His collaborations with Hammerstein, in particular, are celebrated for bringing the Broadway musical to a new maturity by telling stories that were focused on characters and drama rather than the earlier light-hearted entertainment of the genre.

Rodgers was the first person to win all four of the top American entertainment awards in theater, film, recording, and television – an Emmy, a Grammy, an Oscar, and a Tony – now known collectively as an EGOT.[1] In addition, he was awarded a Pulitzer Prize, making him the first ever to receive all five awards (later joined by Marvin Hamlisch).[2] In 1978, Rodgers was in the inaugural group of Kennedy Center Honorees for lifetime achievement in the arts.[3]

Early life

[edit]

Rodgers was born into a Jewish family in Queens, New York, the son of Mamie (Levy) and Dr. William Abrahams Rodgers, a prominent physician who had changed the family name from Rogazinsky. Rodgers began playing the piano at the age of six. He attended P.S. 166, Townsend Harris Hall and DeWitt Clinton High School. Rodgers spent his early teenage summers in Camp Wigwam (Waterford, Maine) where he composed some of his first songs.[5]

Rodgers, Lorenz Hart, and later collaborator Oscar Hammerstein II all attended Columbia University. At Columbia, Rodgers joined the Pi Lambda Phi fraternity. In 1921, Rodgers shifted his studies to the Institute of Musical Art (now the Juilliard School).[6] Rodgers was influenced by composers such as Victor Herbert and Jerome Kern, as well as by the operettas his parents took him to see on Broadway when he was a child.

Career

[edit]Rodgers and Hart

[edit]

In 1919, Richard met Lorenz Hart, thanks to Phillip Levitt, a friend of Richard's older brother. Rodgers and Hart struggled for years in the field of musical comedy, writing several amateur shows. They made their professional debut with the song "Any Old Place With You", featured in the 1919 Broadway musical comedy A Lonely Romeo. Their first professional production was the 1920 Poor Little Ritz Girl, which also had music by Sigmund Romberg. Their next professional show, The Melody Man, did not premiere until 1924.

When he was just out of college Rodgers worked as musical director for Lew Fields. Among the stars he accompanied were Nora Bayes and Fred Allen.[7] Rodgers was considering quitting show business altogether to sell children's underwear, when he and Hart finally broke through in 1925. They wrote the songs for a benefit show presented by the prestigious Theatre Guild, called The Garrick Gaieties, and the critics found the show fresh and delightful. Although it was meant to run only one day, the Guild knew they had a success and allowed it to re-open later. The show's biggest hit—the song that Rodgers believed "made" Rodgers and Hart—was "Manhattan". The two were now a Broadway songwriting force.

Throughout the rest of the decade, the duo wrote several hit shows for both Broadway and London, including Dearest Enemy (1925), The Girl Friend (1926), Peggy-Ann (1926), A Connecticut Yankee (1927), and Present Arms (1928). Their 1920s shows produced standards such as "Here in My Arms", "Mountain Greenery", "Blue Room", "My Heart Stood Still" and "You Took Advantage of Me".

With the Depression in full swing during the first half of the 1930s, the team sought greener pastures in Hollywood. The hardworking Rodgers later regretted these relatively fallow years, but he and Hart did write some classic songs and film scores while out west, including Love Me Tonight (1932) (directed by Rouben Mamoulian, who would later direct Rodgers's Oklahoma! on Broadway), which introduced three standards: "Lover", "Mimi", and "Isn't It Romantic?". Rodgers also wrote a melody for which Hart wrote three consecutive lyrics which were either cut, not recorded or not a hit. The fourth lyric resulted in one of their most famous songs, "Blue Moon". Other film work includes the scores to The Phantom President (1932), starring George M. Cohan, Hallelujah, I'm a Bum (1933), starring Al Jolson, and, in a quick return after having left Hollywood, Mississippi (1935), starring Bing Crosby and W. C. Fields.

In 1935, they returned to Broadway and wrote an almost unbroken string of hit shows that ended shortly before Hart's death in 1943. Among the most notable are Jumbo (1935), On Your Toes (1936, which included the ballet "Slaughter on Tenth Avenue", choreographed by George Balanchine), Babes in Arms (1937), I Married an Angel (1938), The Boys from Syracuse (1938), Pal Joey (1940), and their last original work, By Jupiter (1942). Rodgers also contributed to the book on several of these shows.

Many of the songs from these shows are still sung and remembered, including "The Most Beautiful Girl in the World", "My Romance", "Little Girl Blue", "I'll Tell the Man in the Street", "There's a Small Hotel", "Where or When", "My Funny Valentine", "The Lady Is a Tramp", "Falling in Love with Love", "Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered", and "Wait till You See Her".

In 1939, Rodgers wrote the ballet Ghost Town for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, with choreography by Marc Platoff.[8]

Rodgers and Hammerstein

[edit]

Rodgers' partnership with Hart began having problems because of the lyricist's unreliability and declining health from alcoholism. Rodgers began working with Oscar Hammerstein II, with whom he had previously written songs (before ever working with Lorenz Hart). Their first musical, the groundbreaking hit Oklahoma! (1943), is a notable example of a "book musical", a musical play in which the songs and dances are fully integrated into the plot. What was once a collection of songs, dances and comic turns held together by a tenuous plot became a fully integrated narrative. Even though Show Boat is considered to be the earliest example of a book musical, Oklahoma! epitomized the innovations for which Show Boat had laid the groundwork and is considered the first production in American history to be intentionally marketed as a fully integrated musical.[9]

In 1943, Richard Rodgers became the ninth president of the Dramatists Guild of America. In November that year he and Hart mounted a revival of A Connecticut Yankee; Hart died from alcoholism and pneumonia just days after its opening.

Rodgers and Hammerstein went on to create four more hits that are among the most popular in musical history. Each was made into a successful film: Carousel (1945), South Pacific (1949, winner of the 1950 Pulitzer Prize for Drama), The King and I (1951), and The Sound of Music (1959). Other shows include the minor hit Flower Drum Song (1958), as well as relative failures Allegro (1947), Me and Juliet (1953), and Pipe Dream (1955). They also wrote the score to the film State Fair (1945) (which was remade in 1962 with Pat Boone) and a special TV musical of Cinderella (1957).

Their collaboration produced many well-known songs, including "Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin'", "People Will Say We're in Love", "Oklahoma" (which also became the state song of Oklahoma), "It's A Grand Night For Singing", "If I Loved You", "You'll Never Walk Alone", "It Might as Well Be Spring", "Some Enchanted Evening", "Younger Than Springtime", "Bali Hai", "Getting to Know You", "My Favorite Things", "The Sound of Music", "Sixteen Going on Seventeen", "Climb Ev'ry Mountain", "Do-Re-Mi", and "Edelweiss", Hammerstein's last song.

Much of Rodgers' work with both Hart and Hammerstein was orchestrated by Robert Russell Bennett. Rodgers composed twelve themes, which Bennett used in preparing the orchestra score for the 26-episode World War II television documentary Victory at Sea (1952–53). This NBC production pioneered the "compilation documentary"—programming based on pre-existing footage—and was eventually broadcast in dozens of countries. The melody of the popular song "No Other Love" was later taken from the Victory at Sea theme entitled "Beneath the Southern Cross". Rodgers won an Emmy for the music for the ABC documentary Winston Churchill: The Valiant Years, scored by Eddie Sauter, Hershy Kay, and Robert Emmett Dolan. Rodgers composed the theme music, "March of the Clowns", for the 1963–64 television series The Greatest Show on Earth, which ran for 30 episodes. He also contributed the main title theme for the 1963–64 historical anthology television series The Great Adventure.

In 1950, Rodgers and Hammerstein received The Hundred Year Association of New York's Gold Medal Award "in recognition of outstanding contributions to the City of New York." Rodgers, Hammerstein, and Joshua Logan won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama for South Pacific.[10] Rodgers and Hammerstein had won a special Pulitzer Prize in 1944 for Oklahoma!.[11]

In 1954, Rodgers conducted the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in excerpts from Victory at Sea, Slaughter on Tenth Avenue and the Carousel Waltz for a special LP released by Columbia Records.

Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals earned a total of 37 Tony Awards, 15 Academy Awards, two Pulitzer Prizes, two Grammy Awards, and two Emmy Awards.

After Hammerstein

[edit]Rodgers composed five new musicals between Hammerstein's death in 1960 and his own in 1979. In chronological order, they are: No Strings (1962), Do I Hear a Waltz? (1965), Two by Two (1970), Rex (1976), and I Remember Mama (1979).[12]

Rodgers wrote both words and music for his first new Broadway project No Strings, which earned two Tony Awards and played 580 shows. The show was a minor hit and featured the song, "The Sweetest Sounds".

Rodgers also wrote both the words and music for two new songs used in the film version of The Sound of Music. (Other songs in that film were from Rodgers and Hammerstein.)

Each of his final Broadway musicals faced a declining level of success as Rodgers was overshadowed by up-and-coming composers and lyricists. This was evident by the steady drop in run times and critic reviews. Do I Hear a Waltz? ran 220 performances;Two by Two, 343 performances; Rex only 49 performances; and I Remember Mama, 108 performances.[12]

While Rodgers went on to work with lyricists: Stephen Sondheim (Do I Hear a Waltz?), who was a protégé of Hammerstein, Martin Charnin (Two by Two, I Remember Mama) and Sheldon Harnick (Rex), he never found another permanent partner. These partnerships proved to be unsuccessful as a result of issues of collaboration. Sondheim's reluctance to participate in Do I Hear a Waltz? led to tension between the two. In addition, Charnin and Rodgers were met with opposing ideas when creating Two by Two.[12]

Nevertheless, his overall successful lifetime career did not go unrecognized. At its 1978 commencement ceremonies, Barnard College awarded Rodgers its highest honor, the Barnard Medal of Distinction.

Rodgers was an honoree at the first Kennedy Center Honors in 1978. At the 1979 Tony Awards ceremony—six months before his death—Rodgers was presented the Lawrence Langner Memorial Award for Distinguished Lifetime Achievement in the American Theatre.

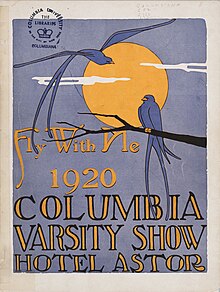

One of Rodger's final works was a revival of Fly With Me for the 1980 Varsity Show, to which he added several new songs. He died less than four months before its premiere in April 1980.[4]

Personal life

[edit]In 1930, Rodgers married Dorothy Belle Feiner (1909–92).[13] Their daughter, Mary (1931–2014), was the composer of Once Upon a Mattress and an author of children's books.[14] The Rodgers later lost a daughter at birth. Another daughter, Linda (1935–2015), also had a brief career as a songwriter. Mary's son and Richard Rodgers's grandson, Adam Guettel (b. 1964), also a musical theater composer, won Tony Awards for Best Score and Best Orchestrations for The Light in the Piazza in 2005. Peter Melnick (b. 1958), Linda Rodgers's son, is the composer of Adrift In Macao, which debuted at the Philadelphia Theatre Company in 2005 and was produced Off-Broadway in 2007. Mary Rodgers' book Shy: The Alarmingly Outspoken Memoirs of Mary Rodgers was published posthumously in 2022, and included her frank revelations and assessments of her father, family and herself.[15]

Rodgers was an atheist.[16] He was prone to depression and alcohol abuse and was at one time hospitalized.

Rodgers was portrayed by Tom Drake in the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer film Words and Music, a semi-fictionalized depiction of the partnership of Rodgers and Hart.

Death

[edit]Rodgers died in 1979, aged 77, after surviving cancer of the jaw, a heart attack, and a laryngectomy. He was cremated, and his ashes were scattered at sea.

Legacy

[edit]In 1990, the 46th Street Theatre was renamed the Richard Rodgers Theatre in his memory. In 1999, Rodgers and Hart were each commemorated on United States postage stamps. In 2002, the centennial year of Rodgers' birth was celebrated worldwide with books, retrospectives, performances, new recordings of his music, and a Broadway revival of Oklahoma!. The BBC Proms that year devoted an entire evening to Rodgers' music, including a concert performance of Oklahoma! The Boston Pops Orchestra released a new CD that year in tribute to Rodgers, entitled My Favorite Things: A Richard Rodgers Celebration.

Alec Wilder wrote the following about Rodgers:

Of all the writers whose songs are considered and examined in this book, those of Rodgers show the highest degree of consistent excellence, inventiveness, and sophistication ... [A]fter spending weeks playing his songs, I am more than impressed and respectful: I am astonished.[17]

Rodgers is a member of the American Theater Hall of Fame.[18]

Along with the Academy of Arts and Letters, Rodgers also started and endowed an award for non-established musical theater composers to produce new productions either by way of full productions or staged readings. It is the only award for which the Academy of Arts and Letters accepts applications and is presented every year. Below are the previous winners of the award:[19]

| Year | Show | Awardee |

|---|---|---|

| 2018[20] | Gun and Powder | Ross Baum |

| Angelica Chéri | ||

| KPOP | Jason Kim | |

| Helen Park | ||

| Max Vernon | ||

| Woodshed Collective | ||

| 2017 | What I Learned from People | Will Aronson |

| Hue Park | ||

| 2016 | We Live in Cairo | Patrick Lazour |

| Daniel Lazour | ||

| Costs of Living | Timothy Huang | |

| Hadestown | Anaïs Mitchell | |

| 2015 | String | Adam Gwon |

| Sarah Hammond | ||

| 2014 | Witness Uganda | Matthew Gould |

| Griffin Matthews | ||

| 2013 | Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812 | Dave Malloy |

| The Kid Who Would Be Pope | Tom Megan | |

| Jack Megan | ||

| 2012 | Witness Uganda | Matthew Gould |

| Griffin Matthews | ||

| 2011 | Dogfight | Peter Duchan |

| Benj Pasek | ||

| Justin Paul | ||

| Gloryana | Andrew Gerle | |

| 2010 | Buddy's Tavern | Raymond De Felitta |

| Alison Louise Hubbard | ||

| Kim Oler | ||

| Rocket Science | Patricia Cotter | |

| Jason Rhyne | ||

| Stephen Weiner | ||

| 2009 | Cheer Wars | Karlan Judd |

| Gordon Leary | ||

| Rosa Parks | Scott Ethier | |

| Jeff Hughes | ||

| 2008 | Alive at Ten | Kirsten A. Guenther |

| Ryan Scott Oliver | ||

| Kingdom | Aaron Jafferis | |

| Ian Williams | ||

| See Rock City and Other Destinations | Brad Alexander | |

| Adam Mathias | ||

| 2007 | Calvin Berger | Barry Wyner |

| Main-Travelled Roads | Dave Hudson | |

| Paul Libman | ||

| 2006 | Grey Gardens | Scott Frankel |

| Michael Korie | ||

| Doug Wright | ||

| True Fans | Chris Miller | |

| Bill Rosenfield | ||

| Nathan Tysen | ||

| Yellow Wood | Michelle Elliott | |

| Danny Larsen | ||

| 2005 | Broadcast | Nathan Christensen |

| Scott Murphy | ||

| Dust & Dreams: Celebrating Sandburg | David Hudson | |

| Paul Libman | ||

| Red | Brian Lowdermilk | |

| Marcus Stevens | ||

| 2004 | To Paint the Earth | Daniel Frederick Levin |

| Jonathan Portera | ||

| The Tutor | Andrew Gerle | |

| Maryrose Wood | ||

| Unlocked | Sam Carner | |

| Derek Gregor | ||

| 2003 | The Devil in the Flesh | Jeffrey Lunden |

| Arthur Perlman | ||

| Once Upon a Time in New Jersey | Susan DiLallo | |

| Stephen A. Weiner | ||

| The Tutor | Andrew Gerle | |

| Maryrose Wood | ||

| 2002 | The Fabulist | David Spencer |

| Stephen Witkin | ||

| The Tutor | Andrew Gerle | |

| Maryrose Wood | ||

| 2001 | Heading East | Leon Ko |

| Robert Lee | ||

| The Spitfire Grill | Fred Alley | |

| James Valcq | ||

| 2000 | Bat Boy | Kaythe Farley |

| Brian Flemming | ||

| Laurence O'Keefe | ||

| The Bubbly Black Girl Sheds Her Chameleon Skin | Kirsten Childs | |

| Suburb | Robert S. Cohen | |

| David Javerbaum | ||

| 1999 | Bat Boy | Kaythe Farley |

| Brian Flemming | ||

| Laurence O'Keefe | ||

| Blood on the Dining Room Floor | Jonathan Sheffer | |

| The Bubbly Black Girl Sheds Her Chameleon Skin | Kirsten Childs | |

| Dream True: My Life with Vernon Dexter | Ricky Ian Gordon | |

| Tina Landau | ||

| The Singing | Lenora Champagne | |

| Daniel Levy | ||

| 1998 | Little Women | Alison Hubbard |

| Allan Knee | ||

| Kim Oler | ||

| Summer | Erik Haagensen | |

| Paul Schwartz | ||

| 1997 | The Ballad of Little Jo | Mike Reid |

| Sarah Schlesinger | ||

| Barrio Babies | Fernand Rivas | |

| Luis Santeiro | ||

| Violet | Brian Crawley | |

| Jeanine Tesori | ||

| 1996 | Bobos | James McBride |

| Ed Shockley | ||

| The Hidden Sky | Kate Chisholm | |

| Peter Foley | ||

| The Princess & the Blac | Andy Chuckerman | |

| Karole Foreman | ||

| 1995 | Spendora | Mark Campbell |

| Stephen Hoffman | ||

| Peter Webb | ||

| 1994 | Doll (not produced) | Scott Frankel |

| Michael Korie | ||

| The Gig | Douglas Cohen | |

| Rent | Jonathan Larson | |

| The Sweet Revenge of ... | Mark Campbell | |

| Burton Cohen | ||

| Stephen Hoffman | ||

| 1993 | Allos Makar | Scott Frankel |

| Michael Korie | ||

| Valeria Vasilevsky | ||

| Avenue X | John Jiler | |

| Ray Leslee | ||

| Christina Alberta's | Polly Pen | |

| They Shoot Horses ... | Nagle Jackson | |

| Robert Sprayberry | ||

| 1992 | Avenue X | John Jiler |

| Ray Leslee | ||

| The Molly Maquires | Sid Cherry | |

| William Strempek | ||

| 1991 | Opal | Robert N. Lindsey |

| The Times | Joe Keenan | |

| Brad Ross | ||

| 1990 | Down the Stream | Michael Goldenberg |

| Swamp Gas and Shallow Feelings | Randy Buck | |

| Shirlee Strother | ||

| Jack E. Williams | ||

| Whatnot | Howard Crabtree | |

| Dick Gallagher | ||

| Mark Waldrop | ||

| 1989 | Juan Darien | Elliot Goldenthal |

| Julie Taymor | ||

| 1988 | Lucky Stiff | Lynn Ahrens |

| Stephen Flaherty | ||

| Sheila Levine is Dead ... | Michael Devon | |

| Todd Graff | ||

| Superbia | Jonathan Larson | |

| 1987 | Henry and Ellen | Michael John LaChiusa |

| Lucky Stiff | Lynn Ahrens | |

| Stephen Flaherty | ||

| No Way to Treat A Lady | Douglas J. Cohen | |

| 1986 | Break/Agnes/Eulogy | Michael John LaChiusa |

| Juba | Wendy Lamb | |

| Russell Walden | ||

| 1984 | Brownstone | Andrew Cadiff |

| Peter Larson | ||

| Josh Rubens | ||

| Papushko | Andrew Teirstein | |

| 1982 | Portrait of Jennie | Enid Futterman |

| Howard Marren | ||

| Dennis Rosa | ||

| 1981 | Child of the Sun | Damien Leake |

| 1980 | Nine (not produced) | Maro Fratti |

| Maury Yeston |

Relationship with performers

[edit]

Rosemary Clooney recorded a version of "Falling in Love with Love" by Rodgers, using a swing style. After the recording session Richard Rodgers told her pointedly that it should be sung as a waltz.[21] After Doris Day recorded "I Have Dreamed" in 1961, he wrote to her and her arranger, Jim Harbert, that theirs was the most beautiful rendition of his song he had ever heard.

After Peggy Lee recorded her version of "Lover", a Rodgers song, with a dramatically different arrangement from that originally conceived by him, Rodgers said, "I don't know why Peggy picked on me, she could have fucked up Silent Night".[22] Mary Martin said that Richard Rodgers composed songs for her for South Pacific, knowing she had a small vocal range, and the songs generally made her look her best. She also said that Rodgers and Hammerstein listened to all her suggestions and she worked extremely well with them.[23] Both Rodgers and Hammerstein wanted Doris Day for the lead in the film version of South Pacific and she reportedly wanted the part. They discussed it with her, but after her manager/husband Martin Melcher would not budge on his demand for a high salary for her, the role went to Mitzi Gaynor.

Awards and nominations

[edit]Rodgers is the first entertainer to have won the EGOT (Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony).

Shows with music by Rodgers

[edit]Lyrics by Lorenz Hart

[edit]- One Minute Please (1917)

- Fly with Me (1920)

- Poor Little Ritz Girl (1920)

- The Melody Man (1924)

- The Garrick Gaieties (1925–26)

- Dearest Enemy (1925)

- The Girl Friend (1926)

- Peggy-Ann (1926)

- Betsy (1926)

- A Connecticut Yankee (1927)

- She's My Baby (1928)

- Present Arms (1928)

- Chee-Chee (1928)

- Spring Is Here (1929)

- Heads Up! (1929)

- Ever Green (1930)

- Simple Simon (1930)

- America's Sweetheart (1931)

- Love Me Tonight (1932)

- Jumbo (1935)

- On Your Toes (1936)

- Babes in Arms (1937)

- I'd Rather Be Right (1937)

- I Married an Angel (1938)

- The Boys from Syracuse (1938)

- Too Many Girls (1939)

- Higher and Higher (1940)

- Pal Joey (1940–41)

- By Jupiter (1942)

- A Connecticut Yankee Revival (1943)

- Rodgers & Hart (1975), Rodgers and Hart revue musical

Lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II

[edit]- Oklahoma! (1943)

- Carousel (1945)

- State Fair (1945) (film)

- Allegro (1947)

- South Pacific (1949)

- The King and I (1951)

- Me and Juliet (1953)

- Pipe Dream (1955)

- Cinderella (1957) (television)

- Flower Drum Song (1958)

- The Sound of Music (1959)

- A Grand Night for Singing (1993), Rodgers and Hammerstein revue musical

- State Fair (1996) (stage musical)

Other lyricists and solo works

[edit]- Ghost Town (1939) (ballet)

- Victory at Sea (1952) (arrangements and orchestration by Robert Russell Bennett)

- The Valiant Years (1960)

- No Strings (1962) (lyrics also by Rodgers)

- Do I Hear a Waltz? (1965) (lyrics by Stephen Sondheim)

- Androcles and the Lion (TV) (1967) (lyrics also by Rodgers)

- Two by Two (1970) (lyrics by Martin Charnin)

- Rex (1976) (lyrics by Sheldon Harnick)

- I Remember Mama (1979) (lyrics by Martin Charnin/Raymond Jessel)

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "In 1962, Richard Rodgers Became the First EGOT (Before That Was Even a Thing)". billboard.com. May 19, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ "Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II". pulitzer.org. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ "KENNEDY CENTER HONORS 1978". paleycenter.org. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ a b "Sing a Song of Morningside". The Varsity Show. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ Hyland, William G: Richard Rodgers The New York Times, Chapter 1. Yale University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-300-07115-9

- ^ Richard Rodgers, Musical Stages: An Autobiography (2002 Reissue), pp. 12,20–21,44, DaCapo Press, ISBN 0-306-81134-0

- ^ Rodgers & Hammerstein as mystery guests on What's My Line?, February 19, 1956, video on YouTube

- ^ Anna Kisselgoff, "DANCE REVIEW; Rodgers As Ideal Dance Partner", The New York Times, October 23, 2002.

- ^ O'Leary, J. (2014). Oklahoma!, "lousy publicity," and the politics of formal integration in the American Musical Theater. Journal of Musicology, 31(1), 139–182. https://doi.org/10.1525/jm.2014.31.1.139

- ^ "Drama". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ "Special Awards and Citations". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ a b c Block, Geoffrey (2003). "After Hammerstein". Richard Rodgers. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09747-4. JSTOR j.ctt1npq43.

- ^ "Dorothy Rodgers". Rodgers and Hammerstein. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ^ Simonson, Robert (June 26, 2014). "Mary Rodgers, Composer of Once Upon a Mattress and Daughter of Broadway Royalty, Dies at 83". Playbill. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ Rodgers, Mary & Green, Jesse,Shy: The Alarmingly Outspoken Memoirs of Mary Rodgers (2022). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0374298623

- ^ Rodgers' biographer William G Hyland states: "That Richard Rodgers would recall, at the very beginning of his memoirs, his great-grandmother's death and its religious significance for his family suggests his need to justify his own religious alienation. Richard became an atheist, and as a parent, he resisted religious instruction for his children. According to his wife, Dorothy, he felt that religion was based on "fear" and contributed to "feelings of guilt." " Richard Rodgers, Yale University Press 1998, ISBN 0-300-07115-9. Chapter 1 at The New York Times Books (accessed April 30, 2008).

- ^ Wilder, Alec, 1973. American Popular Song: The Great Innovators, 1900–1950, Oxford University Press: 163. ISBN 0-19-501445-6.

- ^ "Theater Hall of Fame members". Retrieved February 9, 2014.

- ^ "Awards". American Academy of Arts and Letters.

- ^ "Two Musicals Win Richard Rodgers Awards" (Press release). American Academy of Arts and Letters. March 23, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ Lehman, David (2009). A Fine Romance. New York: Random House. p. 140,249. ISBN 978-0-8052-4250-8.

- ^ Lehman, p. 140.

- ^ Lehman, p. 142–43.

- ^ "The 18th Academy Awards (1946) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved August 16, 2011.

- ^ "Richard Rodgers". Grammy Awards. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "Trustees Award". Grammy Awards. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "Richard Rodgers". Kennedy Center Honors. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "Richard Rodgers". Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II". Pulitzer Prize. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ "1950 Pulitzer Prize Winners & Finalists". Pulitzer Prize. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "1950 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "1952 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "1956 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "1959 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "1960 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "1962 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "1962 Special Tony Award". Tony Awards. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "1965 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "1972 Special Tony Award". Tony Awards. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "1979 Special Tony Award". Tony Awards. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "1996 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Secrest, Meryle (2001). Somewhere For Me. Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc. ISBN 1-55783-581-0.

External links

[edit]| Archives at | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| How to use archival material |

- Richard Rodgers at the Internet Broadway Database

- Richard Rodgers at IMDb

- Richard Rodgers at Playbill Vault

- City Journal article on Rodgers

- Centennial features on Rodgers

- The Richard Rodgers Collection at the Library of Congress

- Richard Rodgers papers, 1914–1989, held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Musicals by Rodgers and Hammerstein

- TimeLine of Rodgers' Life

- Review and analysis of Rodgers' later plays

- "American Masters: Richard Rodgers Biography". PBS. February 1999. Retrieved March 28, 2007.

- A feature on Rodgers and Hammerstein.

- Richard Rodgers at Library of Congress

- Richard Rodgers recordings at the Discography of American Historical Recordings.

- 1902 births

- 1979 deaths

- 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century American composers

- Jewish American atheists

- American atheists

- American ballet composers

- American musical theatre composers

- American people of German-Jewish descent

- Best Original Song Academy Award–winning songwriters

- Broadway composers and lyricists

- Burials at sea

- Columbia College (New York) alumni

- DeWitt Clinton High School alumni

- Grammy Award winners

- Jewish American songwriters

- Male musical theatre composers

- Musicians from Queens, New York

- Primetime Emmy Award winners

- Pulitzer Prize for Drama winners

- Pulitzer Prize winners

- Pupils of Percy Goetschius

- Songwriters from New York (state)

- Special Tony Award recipients

- Tony Award winners

- Townsend Harris High School alumni

- Kennedy Center honorees