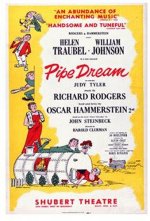

Pipe Dream (musical)

| Pipe Dream | |

|---|---|

Original Broadway poster (1955) | |

| Music | Richard Rodgers |

| Lyrics | Oscar Hammerstein II |

| Book | Oscar Hammerstein II |

| Basis | Sweet Thursday, a novel by John Steinbeck |

| Productions | 1955 Broadway |

Pipe Dream is the seventh musical by the team of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II; it premiered on Broadway on November 30, 1955. The work is based on John Steinbeck's novel Sweet Thursday—Steinbeck wrote the novel, a sequel to Cannery Row, in the hope of having it adapted into a musical. Set in Monterey, California, the musical tells the story of the romance between Doc, a marine biologist, and Suzy, who in the novel is a prostitute; her profession is only alluded to in the stage work. Pipe Dream was not an outright flop but was a financial disaster for Rodgers and Hammerstein.

Broadway producers Cy Feuer and Ernie Martin held the rights to Sweet Thursday and wanted Frank Loesser to compose a musical based on it. When Loesser proved unavailable, Feuer and Martin succeeded in interesting Rodgers and Hammerstein in the project. As Hammerstein adapted Sweet Thursday, he and Rodgers had concerns about featuring a prostitute as female lead and setting part of the musical in a bordello. They signed operatic diva Helen Traubel to play Fauna, the house madam.

As the show progressed through tryouts, Hammerstein repeatedly revised it, obscuring Suzy's profession and the nature of Fauna's house. Pipe Dream met with negative reviews and rapidly closed once it had exhausted its advance sale. It had no national tour or London production and has rarely been presented since. No movie version of the show was made; the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization (which licenses their works) once hoped for a film version featuring the Muppets, with Fauna played by Miss Piggy.

Inception

[edit]

Following World War II, Cy Feuer and Ernie Martin started producing musicals together. Feuer was the former head of the music department at low-budget Republic Pictures; Martin was a television executive. Having secured the rights to the farce Charley's Aunt, they produced it as the musical comedy Where's Charley?, with a score by Frank Loesser. Among the backers of Where's Charley? were Rodgers and Hammerstein, which helped secure additional investment. The show was a hit and helped establish Feuer and Martin on Broadway[1]—they went on to produce Guys and Dolls.[2]

In the aftermath of Guys and Dolls's success, Feuer and Martin were interested in adapting John Steinbeck's 1945 novel Cannery Row into a musical. They felt that some of the characters, such as marine biologist Doc, would work well in a musical, but that many of the other characters would not. Steinbeck suggested that he write a sequel to Cannery Row that would feature the characters attractive to Feuer and Martin. Based on suggestions for the story line by Feuer and Martin, Steinbeck began to write Sweet Thursday.[3]

Cannery Row is set in Monterey, California, before World War II. In Sweet Thursday, Doc returns from the war to find Cannery Row almost deserted and many of his colorful friends gone. Even his close friend Dora, who ran the Bear Flag Restaurant, a whorehouse, has died, and her sister Fauna has taken her place as madam.[4] A former social worker, Fauna teaches the girls how to set a table properly, hopeful they will marry wealthy men.[5] Doc's friends Mack (Mac in Pipe Dream) and Hazel (both men) are still around. They decide Doc's discontent is due to loneliness, and try to get him together with Suzy, a prostitute who has just arrived in Monterey. The two have a brief romance; disgusted by her life as a hooker, Suzy leaves the bawdy house and moves into an abandoned boiler. She decides she cannot stay with Doc, but tells her friends that if Doc fell ill, she would care for him. The accommodating Hazel promptly breaks Doc's arm as he sleeps, bringing the two lovers back together. At the end, Doc and Suzy go off to La Jolla to collect marine specimens together.[4]

Originally, Feuer, Martin and Steinbeck intended the work to be composed by Loesser, but he was busy with a project which eventually became The Most Happy Fella.[3] With Loesser's refusal, Feuer and Martin approached Rodgers and Hammerstein with their project, then titled The Bear Flag Café. From the beginning, the prudish Hammerstein was uncomfortable with the setting, telling Feuer "We do family shows."[6] However, Hammerstein found himself attracted to the characters. Doc and Suzy were culturally mismatched but drawn to each other, with Doc rather moody and Suzy somewhat intense. Similar pairings had led to success, not only in the pair's Carousel and South Pacific, but in Hammerstein's work before his collaboration with Rodgers, such as The Desert Song and Rose-Marie.[7] During early 1953, Steinbeck sent Hammerstein early drafts of the novel. Rodgers was also concerned about the idea of having a prostitute be the female lead, but eventually gave in.[2] The two agreed to write and produce the adaptation.[8]

As they worked with Steinbeck, Rodgers and Hammerstein, though renowned for such hits as Oklahoma!, Carousel, and South Pacific, suffered a relative failure with the 1953 musical Me and Juliet, a tale of romance among the cast and stagehands backstage at a musical.[9] Before agreeing to do the Sweet Thursday project, the duo had considered other projects for their next work together, such as an adaptation of the film Saratoga Trunk. A proposal made by attorney David Merrick to adapt a series of works by Marcel Pagnol to which Merrick held the stage rights fell through when the duo were not willing to have Merrick be an associate producer; Merrick took the project elsewhere, and it was developed into the hit Fanny. Afterwards, Hammerstein stated, "Why the hell did we give up Fanny? What on earth were we trying to prove? My God, that's a great story and look at some of the junk we've done!"[10]

Writing and casting

[edit]

Steinbeck continued to write in late 1953 while Hammerstein and Rodgers went to London to produce the West End production of The King and I. As Hammerstein received new material from Steinbeck, he and Rodgers began to map out the musical, conceiving scenes and deciding where songs should be placed. On January 1, 1954, following the completion of Steinbeck's novel, Hammerstein began to write dialogue and lyrics. Sweet Thursday was published in early 1954 to mixed reviews. Steinbeck later commented, "Some of the critics are so concerned for my literary position that they can't read a book of mine without worrying where it will fit in my place in history. Who gives a damn?"[11] By that time, Rodgers and Hammerstein were busy producing the film version of Oklahoma![11]

For the part of bordello-keeper Fauna, the duo fixed on the famous diva, Helen Traubel.[12] There was precedent for such casting—former opera star Ezio Pinza had starred as suave Frenchman Emile de Becque in South Pacific, and had received rave reviews for his performance.[13] Traubel, in addition to being well known for her Wagnerian roles, was also noted for her nightclub singing.[14] In 1953, the new Metropolitan Opera impresario, Rudolf Bing, feeling that she was lowering the tone of the house, declined to renew her contract.[15] Hammerstein had seen Traubel at her first appearance at the Copacabana nightclub in New York, and afterwards had gone backstage to predict to Traubel that she would be coming straight to Broadway. He saw her show again in Las Vegas several months later, and offered her the part.[16] When offered the role, Traubel eagerly accepted,[15] though she later noted that she had never represented herself as much of an actress.[17]

From the beginning of the project, Feuer and Martin wanted Henry Fonda (who was married to Oscar Hammerstein's stepdaughter Susan Blanchard) to play Doc. The actor put in months of lessons in an attempt to bring his voice up to standard. Fonda later stated that at the end of six months of singing lessons, he "still couldn't sing for shit".[12] Following his first audition for Rodgers, Fonda asked the composer for his honest view, and Rodgers stated, "I'm sorry, it would be a mistake."[12]

Cy Feuer remembered:

So finally, after we go through all this, we turn [Fonda] over to Rodgers and Hammerstein and he's out. Oscar didn't want Fonda because Fonda was his son-in-law and besides Dick said, "I have to have singers," and he hires Helen Traubel to play the madam and she turns out to get top billing and Doc is now the second lead![12]

The duo eventually settled for William Johnson, who had played the male lead in a touring company of Annie Get Your Gun, which they had produced, to play the role of Doc.[18]

There are conflicting accounts of who was the first choice for the role of the itinerant prostitute, Suzy. By some accounts, Rodgers and Hammerstein attempted to get Julie Andrews. Andrews remembers auditioning for both men and being asked by Rodgers if she had been auditioning for other shows. When Andrews said she auditioned for a new musical Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe had written based on George Bernard Shaw's play Pygmalion, tentatively titled My Lady Liza, Rodgers responded "If they ask you to do that show, I think you should do it. If they don't, please let us know because we would love to use you." Andrews's role, as Eliza Doolittle in My Fair Lady, would launch her to stardom. Another candidate was Janet Leigh, whom Rodgers admired greatly, but the actress proved to be unavailable. The producers settled on Judy Tyler, auditioned after Rodgers spotted her on television while watching The Howdy Doody Show,[19] in which she appeared as Princess Summerfall Winterspring.[15]

To direct the play, the duo engaged Harold Clurman, noted for his work in drama and one of the founders of the Group Theatre. Jo Mielziner, veteran of several Rodgers and Hammerstein productions, was the stage designer. In contrast to the complex staging of Me and Juliet, Mielziner's sets were uncomplicated, a system of house-frame outlines in front of backdrops representing Monterey.[20] Boris Runanin was the choreographer, Robert Russell Bennett provided orchestrations, and Salvatore Dell'Isola conducted.[21] The two producers had hoped to hire the prestigious Majestic Theatre, where South Pacific had run, but the writing process took too long, and the Majestic was lost to Fanny.[20] Instead, they booked the Shubert Theatre, in the top rank of Broadway theatres, but not as prestigious as the Majestic.[20] Uniquely for their joint work, they solicited no backers, but underwrote the entire cost themselves.[22] Feuer later said of the bargain he and Martin had made with Rodgers and Hammerstein, "And the deal was pretty good: 50 percent of the producers' end. And we thought, We're rich! And we turned it over to them and they destroyed it."[11]

Rehearsals and tryouts

[edit]

When rehearsals opened in September 1955, Rodgers assembled the cast and told them that he was going into the hospital for a minor operation. In fact, Rodgers had been diagnosed with cancer of the jawbone. He spent the weekend before the operation writing one final song for Pipe Dream. The surgery required removal of part of the jawbone and tongue, and some of the lymph nodes. The operation took place on September 21, 1955; within ten days of the operation he was back in the theatre watching rehearsals, though for some time only as a spectator.[23]

After rehearsals began, Steinbeck wrote to Hammerstein to express his delight at the adaptation. He became more dismayed as the play was slowly revised in rehearsal and during the tryouts. According to Traubel, the play was being "cleaned up ... as scene after scene became emasculated".[24] The revisions made Suzy's profession less clear, and also fudged the nature of Fauna's house. One revision removed Suzy's police record for "vagrancy".[24] These changes were sparked by the fact that audience members at the tryouts in New Haven and Boston were uncomfortable with the setting and Suzy's role;[25] by the time the revisions were completed, the script could be read to say that Suzy was merely boarding at Fauna's.[24]

Steinbeck noted this tendency on a page of dialogue changes:

"One of the most serious criticisms is the uncertainty of Suzy's position in the Bear Flag. It's either a whore house, or it isn't. Suzy either took a job there, or she didn't. The play doesn't give satisfaction here and it leaves an audience wondering. My position is that she took the job all right but she wasn't any good at it. In the book, Fauna explains that Suzy's no good as a hustler because she's got a streak of lady in her. I wish we could keep this thought because it explains a lot in a short time."[26]

In another memo, Steinbeck noted that the pathos of Suzy being a prostitute had given much of the dramatic tension to the scene in which Doc rejects Suzy, and later, her rejection of him. "I think if you will finally bring the theme of this play into the open, but wide open, you will have solved its great weakness and have raised it to a high level ... If this is not done, I can neither believe nor take Pipe Dream seriously."[27]

In the end, Suzy's activities at the Bear Flag were glossed over, as Hammerstein concentrated on her relationship with Doc. Alluding to Hammerstein's emphasis on the scene in which Suzy makes Doc soup after Hazel breaks his arm, Steinbeck stated, "You've turned my prostitute into a visiting nurse!"[28]

Plot

[edit]The action of the play is in the mid-1950s, and takes place on Cannery Row in Monterey, California. In the Steinbeck book which forms the basis for the musical, the Bear Flag is a bordello and Suzy a prostitute. This is alluded to in the musical, but never expressed outright.

Act 1

[edit]

In the early morning hours, marine biologist Doc is already at work in his one-man Western Biological Laboratory, getting an order of starfish ready to be shipped to a university. His unintelligent friend Hazel (a man) comes in to chat with him ("All Kinds of People"). Millicent, a wealthy young lady, enters from the next room, where she has been spending (part of) the night with Doc. Mac, another friend of Doc, brings in Suzy, who has injured her hand breaking a window to steal some donuts. Doc, whose lack of a medical degree does not stop the denizens of Cannery Row from seeking him out for treatment, bandages her hand, as the irritated Millicent leaves. Suzy, new in town, is curious about Doc's work ("The Tide Pool") and tells about her journey from San Francisco ("Everybody's Got a Home but Me"). Fauna, who runs the nearby Bear Flag Café—an establishment open even at this hour—had heard that a new girl in town had injured herself, and has come to talk to Suzy. Fauna is initially reluctant to invite Suzy into the Bear Flag, but when Jim, the local plainclothes cop gives Suzy a hard time, Fauna takes Suzy in. Suzy is fully aware of what kind of a place it is.

The Palace Flophouse, where Mac, Hazel, and other locals reside, is a storage shed behind the Chinese store now owned by Joe the Mexican, and the Flophouse residents muse on their awkward path through life ("A Lopsided Bus"). Fauna comes by briefly to tell Hazel that she has run his "horror scope" and that he will one day be President. The Flophouse boys have a problem: Joe the Mexican acts unaware that he owns the shed; he has not appeared to either demand rent or to kick them out. They would like to know whether Joe is aware of his ownership, without tipping him off. The boys come up with the idea of raffling off their shed, with the raffle rigged so that Doc, who would not kick them out, will be the winner. The prize money will allow Doc to buy the microscope he needs for his scientific work. They sound out Joe about the scheme; he offers to sell tickets in his store and displays no awareness that he owns the shed.

Suzy and Doc are attracted to each other; she has in fact been quietly tidying his rooms while he is down at the tide pool catching specimens ("The Man I Used to Be"). Fauna tries to persuade Doc, who is very successful with the ladies, to woo Suzy. When Doc is dismissive, Fauna explains that she wants to get Suzy out of the Bear Flag when it is taken over for the night by a private party. Doc agrees to take Suzy out and treat her like a lady. Fauna goes back to the Bear Flag ("Sweet Thursday"), and works to give Suzy confidence ("Suzy is a Good Thing"). Doc and Suzy's date is the source of great interest to the people of Cannery Row. Both are nervous; Doc wears an unaccustomed necktie, while Suzy tries to act like a lady, but her polish wears thin at times. ("All At Once You Love Her"). At the end of the meal, they decide to continue the evening on a secluded sand dune.

Act 2

[edit]

The next morning, the girls of the Bear Flag are exhausted; the members of the private party wore them out. They wonder how Suzy's date with Doc went. Although it is only July, Fauna is busy ordering the Bear Flag's Christmas cards ("The Happiest House on the Block"). Suzy comes in and tells Fauna of the date; that Doc made no pass at her, and that Doc confided how lonely he is. She is convinced Doc "don't need nobody like me"; he needs a wife. Fauna is encouraging, but Suzy believes that Doc, knowing what he does of her history and work, will not want her. The Flophouse is to host a fancy dress party the following night, at which the raffle is to take place—Fauna proposes that at the party, Suzy sing "Will You Marry Me?" to Doc. Suzy is still nervous; Fauna reminds her that the previous night, Doc did not treat her like a tramp, and she did not act like one. As word spreads of the celebration, the community becomes enthusiastic about the get-together ("The Party That We're Gonna Have Tomorrow Night")

At the Flophouse, a wild celebration takes place. Fauna, at first in the costume of a witch, seems to transform her costume into that of a Fairy Godmother. After some sleight of hand with the tickets, Doc wins the raffle, to the surprise of some. When Suzy comes out in a white bride's dress and sings her lines, Doc is unimpressed, and Suzy is humiliated. As both stalk off in opposite directions, the party disintegrates into a brawl.

Suzy gets a job at a burger joint, and moves into an abandoned boiler, with entry through the attached pipe. Doc is unhappy, and Hazel decides something has to be done ("Thinkin' "). He is unable to come up with an answer, and eventually forgets the question. Some weeks pass, and Joe the Mexican woos Suzy. He has no success, and his attempts irritate Doc. The next day, Doc himself approaches the pipe with flowers in hand ("How Long?"), still uncertain as to why he is seeking a girl like Suzy. Suzy lets him in the boiler, which she has fitted up in a homelike manner. She is doing well at the burger joint, but is grateful to Fauna for giving her confidence. She is confident enough, indeed, to reject Doc, who is unhappy, but philosophical ("The Next Time It Happens").

Hazel sees Doc even more dispirited than before, and asks Suzy for an explanation. Suzy says that she is not willing to go over and be with Doc, but "if he was sick or if he bust his leg or an arm or something", she would go to him and bring him soup. The wheels in Hazel's head begin unaccustomed turnings, and sometime later when Mac passes Hazel on the street, Mac is surprised to see his friend carrying a baseball bat. When the scene returns to Doc's lab, he is receiving treatment from a real doctor and trying to puzzle out how he broke his arm. Suzy comes in, and makes soup for him as Hazel and Mac take turns watching at the keyhole. Doc admits that he needs and loves Suzy, and they embrace. As Fauna and the girls arrive, so do the other Flophouse boys, and Mac gives Doc what was bought with the raffle money—the largest (tele)scope in the catalog. ("Finale")

Musical numbers

[edit]|

Act I[21]

|

Act II[18]

|

Productions

[edit]

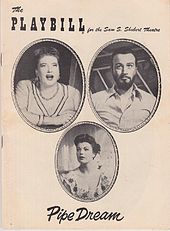

Pipe Dream premiered on Broadway on November 30, 1955, at the Shubert Theatre, with Helen Traubel as Fauna, William Johnson as Doc, Judy Tyler as Suzy, George D. Wallace as Mac and Mike Kellin as Hazel.[21] The show had received the largest advance ticket sale in Broadway history to that point, $1.2 million.[29] Some of Steinbeck's ill-feeling was removed on the second night, which he attended and then went backstage to greet the cast. After a celebratory dinner at Sardi's during which the manager sent champagne to his table, he said to his wife Elaine, "Isn't the theatre marvelous?"[30] The author held no grudge; he later told Hammerstein that he accepted that Rodgers and Hammerstein were ultimately responsible for the show and had the right to make changes.[29]

Rodgers and Hammerstein had not permitted group sales, so-called "theatre parties" for their shows. They lifted the ban for Pipe Dream, and pre-sold theatre party sales helped keep the show going, as there were few sales after opening night given the dismal reviews. More than 70 performances were entirely sold to groups. In March 1956, in a final attempt to save the show, Rodgers and Hammerstein revised it somewhat, moving several musical numbers. Traubel missed a number of performances due to illness, and left when her contract expired a few weeks before the show closed in June 1956—she was replaced by Nancy Andrews.[31] Traubel's understudy, Ruth Kobart, played 42 of the show's 245 performances.[32]

Pipe Dream was nominated for nine Tony Awards; it lost for best musical to the only other nominee, Damn Yankees.[33] Alvin Colt was the sole winner, for Best Costume Design.[34] Johnson died of a heart attack within a year of Pipe Dream's closing; Tyler died in an automobile accident during the same timespan.[33] These tragedies convinced Traubel that there was a curse attached to Pipe Dream, and she began carrying good-luck charms when she performed.[32]

The poor reviews of Pipe Dream made a national tour or London run impractical. Subsequent productions have been extremely rare.[25] In 1981, a community theatre production of Pipe Dream was presented by the Conejo Players Theatre in Thousand Oaks, California. Los Angeles Times critic Dan Sullivan admired the small-scale staging, but called the show "the emptiest musical that two geniuses ever wrote" and said of it, "imagine a song ['The Happiest House on the Block'] about a bawdyhouse which describes the goings-on there after midnight as 'friendly, foolish and gay'".[35] In 1995 and 2002, 42nd Street Moon presented it as a staged concert.[32] It was presented in March–April 2012 by New York City Center Encores!,[36] also as a staged concert;[37] the cast featured Will Chase (Doc), Laura Osnes (Suzy), Leslie Uggams (Fauna), Stephen Wallem (Hazel) and Tom Wopat (Mac).[38] In July and August 2013 it was presented by London's small Union Theatre, directed by Sasha Regan.[39][40] No film version was contemplated in the authors' lifetimes.[25] The Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization, which licenses the pair's works, proposed a film version with the Muppets. Humans would play Doc and Suzy; Muppets would play the other roles—with Miss Piggy as Fauna.[30]

Music and recordings

[edit]

Despite the poor reviews of the musical, Rodgers was given credit for an imaginative score. "Sweet Thursday" is a cakewalk, unusual for Rodgers who rarely wrote them. However, Rodgers biographer William Hyland suggests that "Sweet Thursday" was out of character for Traubel's voice.[41] Hyland also speculates that "The Next Time It Happens", a duet for Suzy and Doc as they decide their love will not work, needed to be more melancholy, and Doc's "The Man I Used To Be" more of a lament rather than having a lively melody.[42] According to Broadway writer Ken Mandelbaum, "Pipe Dream contains a generally fascinating score."[33] He terms Suzy's "Everybody's Got a Home but Me", a "gorgeous ballad of yearning".[33]

During rehearsals and even during the run of the show, the music was repeatedly revised by Rodgers in an attempt to gear the songs to Traubel's voice. According to Bruce Pomahac of the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization, "as she began to get cold feet about what her New York fans would think about her as a belter, the keys of each of her numbers edged upward."[43] One of Traubel's numbers saw three different versions before being scrapped in favor of, according to Pomahac, "something that sounded like an excerpt from Traubel's Vegas act."[43] "All At Once You Love Her" saw some popularity when recorded, during the run of the show, by Perry Como; in what Pomahac speculates was an attempt to appease Traubel, a reprise of the song was added for her, and provided "one of the loveliest moments in all of Pipe Dream".[43] The Organization announced that a new vocal score would be published in 2012, though it has not appeared as of 2017—the existing score reflects revisions made when Nancy Andrews took over the part.[43]

Pipe Dream's songs have been reused in other works. "The Man I Used to Be" and "The Next Time It Happens" were included in the 1996 stage version of Rodgers and Hammerstein's 1945 film musical, State Fair.[44] "The Next Time It Happens" was inserted in David Henry Hwang's revised version of Rodgers and Hammerstein's later work, Flower Drum Song. Used during the show's 2001 Los Angeles run,[45] it was cut before the show reached Broadway in 2002.[46] According to David Lewis in his history of the Broadway musical, "The Rodgers and Hammerstein office has, it would appear, given up on Pipe Dream and [Me and] Juliet ever finding an audience ... so these songs are up for grabs."[47]

Thomas Hischak, in his The Rodgers and Hammerstein Encyclopedia, stated that the original cast album is well-produced, but many of the songs came across better when other artists recorded them.[25] The New York Times suggested that the music had echoes of the duo's earlier works, giving it "a disappointing air of familiarity".[48] The Times praised both Tyler and Johnson for their singing on the album, and while acknowledging that Traubel had difficulty making the transition from opera singer to Broadway belter, wrote that "for the most part, she makes the transfer amiably and effectively".[48] The original cast recording was released on compact disc by RCA Victor Broadway in 1993.[49]

A live album from the Encores! production starring Osnes and Chase was released on September 18, 2012.[50][51] Suskin reviewed it highly favorably, calling the show "a fascinating musical on several counts, and one which displays the rich, vibrant sound of pure Rodgers & Hammerstein. The experience is carried over—perfectly so—to the cast album".[52]

Reception and aftermath

[edit]

The musical received moderate to poor reviews. Brooks Atkinson of The New York Times termed it "a pleasant, lazy romance ... Mr. Rodgers and Mr. Hammerstein in a minor key".[53] John Chapman of the Daily News stated, "Perhaps Hammerstein and Rodgers are too gentlemanly to be dealing with Steinbeck's sleazy and raffish denizens."[29] Walter Kerr of the Herald Tribune suggested, "Someone seems to have forgotten to bring along that gallon of good, red wine."[28] John McClain of the Journal-American stated, "This is a far cry from the exalted talents of the team that produced South Pacific. They must be human, after all."[54] Billboard magazine echoed many reviewers in generally praising Rodgers's melodies and Hammerstein's lyrics, while criticizing the latter's libretto: "a cumbersome soporific."[55] Steven Suskin, in his book chronicling Broadway opening night reviews, stated that Pipe Dream received one favorable review from the seven major New York critics, two mixed, and four unfavorable.[56] Louis Kronenberger, in Time magazine, summed it up as "[p]roficient, professional, and disappointing."[57] Billy Rose said of Pipe Dream, "You know why Oscar shouldn't have written that? The guy has never been in a whorehouse in his life."[58]

Publicly, Hammerstein accepted blame for himself and Rodgers, and stated that had the musical been produced by anyone else, "we'd say that these are producers we wouldn't like to work with again".[22] According to Cy Feuer, Hammerstein privately blamed him and Martin, telling them, "We believed your pitch and we went and did something we were never cut out to do and we should never have done it.[22] In 2011, Smithsonian Magazine ranked Pipe Dream as #1 among the all-time Broadway flops.[59]

According to author Frederick Nolan, who chronicled the works of Rodgers and Hammerstein, Pipe Dream "cost them a fortune".[22] Rodgers later stated it was the only one of their works he truly disliked; that if you start with a bad idea, everything is marred by that: "We shouldn't have been dealing with prostitutes and tramps."[42] Rodgers also blamed the casting of Traubel, whom he considered wrong for the part. Hammerstein's grandson, Oscar A. Hammerstein, in his book about his family, agreed with Rodgers's view of Traubel—"too much Brunhilde, [sic] not enough Miss Kitty [the barkeeper on Gunsmoke]".[60] The elder Hammerstein's biographer, Hugh Fordin, tied the failure of the play to the lyricist's prudery:

South Pacific, Carousel and [Hammerstein work] Carmen Jones have stories that rest on the power of sexual attraction. As long as the sexuality was implicit, Oscar could treat it with the same understanding that he brought to other aspects of human behavior ... His problem was with dealing openly with sexual material; because of this reticence, Pipe Dream was not what it might have been.[29]

Awards and nominations

[edit]Original Broadway production

[edit]| Year | Award | Category | Nominee | Result | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1956 | Tony Award | Best Musical | Nominated | [61] | |

| Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Musical | William Johnson | Nominated | |||

| Best Performance by a Featured Actor in a Musical | Mike Kellin | Nominated | |||

| Best Performance by a Featured Actress in a Musical | Judy Tyler | Nominated | |||

| Best Direction of a Musical | Harold Clurman | Nominated | |||

| Best Choreography | Boris Runanin | Nominated | |||

| Best Conductor and Musical Director | Salvatore Dell'Isola | Nominated | |||

| Best Scenic Design | Jo Mielziner | Nominated | |||

| Best Costume Design | Alvin Colt | Won | |||

See also

[edit]- Cannery Row, 1982 movie based on the books Cannery Row and Sweet Thursday

References

[edit]- ^ Nolan, p. 228.

- ^ a b Hyland, p. 227.

- ^ a b Nolan, p. 229.

- ^ a b Hyland, pp. 228–229.

- ^ Fordin, p. 323.

- ^ Mordden, p. 168.

- ^ Mordden, p. 170.

- ^ Mordden, p. 169.

- ^ Hyland, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Fordin, p. 322.

- ^ a b c Nolan, p. 230.

- ^ a b c d Nolan, p. 231.

- ^ Hyland, pp. 179–189.

- ^ Hischak, p. 297.

- ^ a b c Mordden, p. 172.

- ^ Fordin, p. 324.

- ^ Fordin, p. 325.

- ^ a b Hischak, p. 219.

- ^ Nolan, p. 232.

- ^ a b c Mordden, pp. 172–173.

- ^ a b c Hischak, p. 218.

- ^ a b c d Nolan, p. 234.

- ^ Hyland, pp. 229–230.

- ^ a b c Fordin, p. 326.

- ^ a b c d Hischak, p. 220.

- ^ Fordin, pp. 326–327.

- ^ Fordin, p. 327.

- ^ a b Mordden, p. 174.

- ^ a b c d Fordin, p. 329.

- ^ a b Mordden, p. 177.

- ^ Block, pp. 245–246.

- ^ a b c Pipe Dream Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. 42nd Street Moon. Retrieved on February 2, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Block, p. 246.

- ^ Hischak, p. 373.

- ^ Sullivan, Dan. Pipe Dream lights up Conejo stage. Los Angeles Times, April 30, 1981, Section VI, p. 4. Retrieved on February 14, 2011. Fee for article.

- ^ Isherwood, Charles (March 29, 2012). "Wholesome Songsmiths Visit Steinbeck's Brothel - 'Pipe Dream,' From Rodgers and Hammerstein, at Encores!". New York Times. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ^ Pipe Dream. New York City Center. Retrieved on March 4, 2012.

- ^ Gans, Andrew. "Tony Winner Leslie Uggams Joins Cast of City Center Encores! 'Pipe Dream' " Archived 2012-02-19 at the Wayback Machine. Playbill.com, February 16, 2012, Retrieved on March 4, 2012

- ^ Pipe Dream. Union Theatre, London. Retrieved on August 8, 2013.

- ^ More Pipe Dream Info. Union Theatre, London. Retrieved on August 8, 2013.

- ^ Hyland, pp. 231–232.

- ^ a b Hyland, p. 232.

- ^ a b c d Pomahac.

- ^ Willis, p. 41

- ^ Lewis, Flower Drum Songs, pp. 149, 158.

- ^ Lewis, Flower Drum Songs, pp. 176–178.

- ^ Lewis, p. 180

- ^ a b Wilson.

- ^ Metcalf.

- ^ RandH.

- ^ Broadway World.

- ^ Suskin, Steven. On the record: Rodgers & Hammerstein's Pope Dream from Encores and Laura Osnes Live Archived 2013-06-05 at the Wayback Machine. Playbill.com, September 23, 2012, Retrieved on June 20, 2013

- ^ Atkinson.

- ^ Suskin, p. 555.

- ^ Francis, Bob. "R&H Fill Their 'Pipe' with Week Tobacco." Billboard, 10 December 1955, 18.

- ^ Suskin, p. 556.

- ^ Hammerstein, p. 213.

- ^ Fordin, p. 328.

- ^ Rhodes, Jesse. "Broadway's Top Ten Musical Flops". smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- ^ Hammerstein, p. 214.

- ^ Hischak, p. 337.

Bibliography

[edit]- Block, Geoffrey, ed. (2006) [2002]. The Richard Rodgers Reader (reprint, illustrated ed.). New York: Oxford University Press (US). ISBN 978-0-19-531343-7.

- Fordin, Hugh (1995) [1977]. Getting to Know Him: A Biography of Oscar Hammerstein II (illustrated, reprint of 1986 ed.). Jefferson, N.C.: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80668-1.[permanent dead link]

- Hammerstein, Oscar Andrew (2010). The Hammersteins: A Musical Theatre Family (illustrated ed.). New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. ISBN 978-1-57912-846-3.

- Hischak, Thomas S. (2007). The Rodgers and Hammerstein Encyclopedia (illustrated ed.). Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-34140-3.

- Hyland, William G. (1998). Richard Rodgers (illustrated ed.). New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07115-3.

- Lewis, David H. (2002). Broadway Musicals: A Hundred Year History. Ned Miller (Composer) "Sunday" (illustrated ed.). Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-1269-3.

- Lewis, David (2006). Flower Drum Songs: The Story of Two Musicals (illustrated ed.). Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland and Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-2246-3.

- Mariska, Bradley (2004). "Who Expects a Miracle to Happen Every Day?": Rediscovering Me and Juliet and Pipe Dream, The Forgotten Musicals of Rodgers and Hammerstein (PDF) (thesis ed.). College Park, MD: University of Maryland.

- Mordden, Ethan (1992). Rodgers & Hammerstein (illustrated ed.). New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-1567-1.

- Nolan, Frederick (2002) [1979]. The Sound of Their Music: The Story of Rodgers and Hammerstein (reprint ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Applause Theatre and Cinema Books. ISBN 978-1-55783-473-7.

- Suskin, Steven (1990). Opening Night on Broadway. New York: Schirmer Books. ISBN 978-0-02-872625-0.

- Willis, John (1998). Theatre World 1995–1996. New York: Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-1-55783-323-5.

Articles and webpages

- Atkinson, Brooks (December 1, 1955). "Theatre: Rodgers and Hammerstein; 'Pipe Dream' Is Based on Steinbeck Novel". The New York Times. p. 44. Retrieved February 3, 2011. (subscription required)

- Metcalf, Steve (February 7, 1993). "Torrent of CD releases showcases Broadway classics and obscurities". Hartford Courant. p. G1. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved January 30, 2011. (subscription required)

- Pomahac, Bruce (January 18, 2011). "Restoring musical classics—Part 3, Pipe Dream". Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization, The. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- Wilson, John S. (February 5, 1956). "Jerome Kern film classics on disks; Two Volumes of Late Master's Music — Some Rodgers and Hammerstein Hits Melodic Spotlight Newer Singer". The New York Times. p. 131, Arts & Leisure. Retrieved February 14, 2011. (subscription required)

- "Encores! Pipe Dream album gets 9/18 release!". Broadway World. August 7, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- "Rodgers & Hammerstein's Pipe Dream to get new live recording!". Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization, The. March 28, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

External links

[edit]