Racine, Wisconsin

Racine, Wisconsin | |

|---|---|

Monument Square | |

| Nickname(s): The Belle City of the Lakes, The Kringle Capital of America, Kringleville, Invention City[1] | |

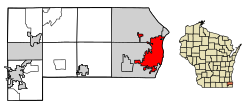

Location of Racine in Racine County, Wisconsin. | |

| Coordinates: 42°43′34″N 87°48′21″W / 42.72611°N 87.80583°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Wisconsin |

| County | Racine |

| Incorporated (village) | February 13, 1841 |

| Incorporated (city) | August 8, 1848 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Cory Mason (D) |

| Area | |

• City | 15.66 sq mi (40.56 km2) |

| • Land | 15.47 sq mi (40.08 km2) |

| • Water | 0.18 sq mi (0.48 km2) |

| Elevation | 618 ft (188 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 77,816 |

| • Rank | 5th in Wisconsin |

| • Density | 4,960.26/sq mi (1,915.13/km2) |

| • Urban | 133,700 (US: 239th) |

| • Metro | 195,041 (US: 221st) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 53401–53408[4] |

| Area code | 262 |

| FIPS code | 55-66000[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1572015[6] |

| Website | cityofracine |

Racine (/rəˈsiːn, reɪ-/ rə-SEEN, ray-)[8] is a city in and the county seat of Racine County, Wisconsin, United States. It is located on the shore of Lake Michigan at the mouth of the Root River, situated 22 miles (35 km) south of Milwaukee and 60 miles (97 km) north of Chicago.[9] As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 77,816, making it the fifth-most populous city in Wisconsin. It is the principal city of the Racine metropolitan statistical area (consisting only of Racine County, 2020 pop. 197,727).[10] The Racine metropolitan area is, in turn, counted as part of the greater Milwaukee combined statistical area.[10]

Racine is the headquarters of several industries, including Case Corporation heavy equipment, S. C. Johnson & Son cleaning and chemical products, Dremel, Reliance Controls, Twin Disc, and Arthur B. Modine heat exchangers. The Mitchell & Lewis Company, a wagonmaker in the 19th century, began making motorcycles and automobiles as Mitchell-Lewis Motor Company at the start of the 20th century. Racine is also home to InSinkErator, manufacturers of the first garbage disposal.[11] Racine was also historically home to the Horlicks malt factory, where malted milk balls were first developed, and the Western Publishing factory where Little Golden Books were printed. Prominent architects in Racine's history include A. Arthur Guilbert and Edmund Bailey Funston, and the city is home to some works by renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

History

[edit]

Human prehistory in Racine began with Paleoindians after the last Ice Age. After the arrival of Europeans, the Historic period saw the Miami and later the Potawatomi expand into the area under the pressures of the French fur trade.

In November 1674, while traveling from Green Bay to the territory of the Illinois Confederation, Father Jacques Marquette and his assistants, Jacques Largillier, Pierre Porteret, and Nathan Kowitt camped at the mouth of the Root River.[12] These were the first Europeans known to visit what is now Racine County. Further expeditions were made in the area by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle in 1679 and by François Jolliet De Montigny and Jean Baptiste Bissot, Sieur de Vincennes in 1698. Nearly a century later, in 1791, a trading post would be established along Lake Michigan near where the Root River empties into it.

Following the Black Hawk War, the area surrounding Racine, which had previously been off-limits, was settled by Yankees from upstate New York and New England. In 1834 Captain Gilbert Knapp USRM, who was from Chatham, Massachusetts, founded the settlement of "Port Gilbert" at the place where the Root River empties into Lake Michigan.[13] Knapp had first explored the area of the Root River valley in 1818, and returned with financial backing when the war ended. Within a year of Knapp's settlement hundreds of other settlers from New England and western New York had arrived and built log cabins in the area surrounding his own. Some of the settlers were from the town of Derby, Connecticut, and others came from the New England states of Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine.[14] The area was previously called "Kipi Kawi" and "Chippecotton" by the indigenous peoples, both names for the Root River. The name "Port Gilbert" was never really accepted, and in 1841 the community was incorporated as the village of Racine, after the French word for "root". After Wisconsin was admitted to the Union in 1848, the new legislature voted in August to incorporate Racine as a city.

In 1852, Racine College, an Episcopal college, was founded; it closed in 1933.[15] Its location and many of its buildings are preserved today by the Community of St. Mary as part of the DeKoven Center.

Also in 1852, Racine High School, the first public high school in Wisconsin, opened. The high school operated until 1926, when it was torn down to make way for the new Racine County Courthouse, an Art Deco highrise. Washington Park High School was built to replace the original high school.[16]

Before the Civil War, Racine was well known for its strong opposition to slavery, with many slaves escaping to freedom via the Underground Railroad passing through the city. In 1854 Joshua Glover, an escaped slave who had made a home in Racine, was arrested by federal marshals and jailed in Milwaukee. One hundred men from Racine, and ultimately 5,000 Wisconsinites, rallied and broke into the jail to free him. He was helped to escape to Canada. Glover's rescue gave rise to many legal complications and a great deal of litigation. This eventually led to the Wisconsin Supreme Court declaring the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 unconstitutional, and later, the Wisconsin State Legislature refusing to recognize the authority of the U.S. Supreme Court.[17] This saga played a significant role in the building up of tensions that preceded the Civil War.

Industry

[edit]Racine was a factory town almost from the beginning. The first industry in Racine County included the manufacture of fanning mills, machines that separate wheat grain from chaff. Racine also had its share of captains of industry, including J. I. Case (heavy equipment), S. C. Johnson & Son (cleaning and chemical products), and Arthur B. Modine (Heat Exchangers). Racine's harbor was central to the shipping industry in Wisconsin in the late 19th century. Racine was also an early car manufacturing center. One of the world's first automobiles was built there in 1871 or 1872 by J. W. Cathcart,[18] as was the Pennington Victoria tricycle,[19][20] the Mitchell,[21] and the Case.[22]

In 1887, malted milk was invented in Racine by English immigrant William Horlick, and Horlicks remains a global brand. The garbage disposal was invented in 1927 by architect John Hammes of Racine, who founded the company InSinkErator, which still produces millions of garbage disposers every year in Racine.[23] Racine is also the home of S.C. Johnson & Son, whose headquarters were designed in 1936 by Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright also designed the Wingspread Conference Center and several homes and other buildings in Racine. The city is also home to the Dremel Corporation, Reliance Controls Corporation and Twin Disc. Case New Holland’s Racine manufacturing facility, which builds two types of tractors (the New Holland T8 and the Case IH Magnum), offers public tours throughout the year.[24]

Historic districts and buildings

[edit]

Racine includes the Old Main Street Historic District. Historic buildings in Racine include the Badger Building, Racine Elks Club, Lodge No. 252, St. Patrick's Roman Catholic Church, YMCA Building, Chauncey Hall House, Eli R. Cooley House, George Murray House, Hansen House, Racine College, McClurg Building, First Presbyterian Church, Memorial Hall, Racine Depot, United Laymen Bible Student Tabernacle, Chauncey Hall Building, Thomas P. Hardy House, and Horlick Field. The area is home to several National Register of Historic Places listed structures: National Register of Historic Places listings in Racine County, Wisconsin. The city is also home to Regency Mall.

Frank Lloyd Wright designed and built the Johnson Wax Headquarters building in Racine. The building was and still is considered a marvel of design innovation, despite its many practical annoyances such as rainwater leaks. Wright urged then-president Hib Johnson to build the structure outside of Racine, a city that Wright, a Wisconsin native, thought of as "backwater." Johnson refused to have the Johnson Wax Headquarters sited anywhere other than Racine.[citation needed]

Geography

[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 15.66 square miles (40.56 km2), of which, 15.47 square miles (40.07 km2) is land and 0.18 square miles (0.47 km2) is water.[25]

Climate

[edit]Racine has a warm-summer Continental climate (Köppen climate classification: Dfb). Summers are warm and short while winters are cold. Precipitation is dispersed evenly throughout the year, although summers are slightly wetter and more humid than winters.

| Climate data for Racine WWTP, Wisconsin (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1896–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 64 (18) |

67 (19) |

83 (28) |

92 (33) |

96 (36) |

106 (41) |

107 (42) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

91 (33) |

79 (26) |

66 (19) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 48.9 (9.4) |

51.9 (11.1) |

64.9 (18.3) |

75.4 (24.1) |

82.8 (28.2) |

89.5 (31.9) |

93.1 (33.9) |

91.1 (32.8) |

86.4 (30.2) |

77.4 (25.2) |

64.3 (17.9) |

53.1 (11.7) |

94.7 (34.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 29.6 (−1.3) |

32.4 (0.2) |

40.8 (4.9) |

50.7 (10.4) |

61.3 (16.3) |

71.9 (22.2) |

78.5 (25.8) |

77.3 (25.2) |

70.5 (21.4) |

58.8 (14.9) |

46.0 (7.8) |

34.8 (1.6) |

54.4 (12.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 22.1 (−5.5) |

25.1 (−3.8) |

33.9 (1.1) |

43.6 (6.4) |

53.5 (11.9) |

64.1 (17.8) |

71.0 (21.7) |

70.4 (21.3) |

63.1 (17.3) |

51.0 (10.6) |

38.9 (3.8) |

27.9 (−2.3) |

47.0 (8.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 14.5 (−9.7) |

17.9 (−7.8) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

36.4 (2.4) |

45.6 (7.6) |

56.3 (13.5) |

63.5 (17.5) |

63.4 (17.4) |

55.7 (13.2) |

43.1 (6.2) |

31.7 (−0.2) |

21.0 (−6.1) |

39.7 (4.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −5.2 (−20.7) |

−0.3 (−17.9) |

9.9 (−12.3) |

26.0 (−3.3) |

37.1 (2.8) |

47.2 (8.4) |

56.1 (13.4) |

55.9 (13.3) |

42.9 (6.1) |

30.6 (−0.8) |

17.5 (−8.1) |

2.2 (−16.6) |

−9.3 (−22.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −31 (−35) |

−24 (−31) |

−12 (−24) |

10 (−12) |

25 (−4) |

33 (1) |

42 (6) |

40 (4) |

28 (−2) |

14 (−10) |

−5 (−21) |

−23 (−31) |

−31 (−35) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.98 (50) |

1.92 (49) |

2.42 (61) |

3.94 (100) |

4.32 (110) |

4.35 (110) |

3.27 (83) |

3.75 (95) |

3.34 (85) |

3.07 (78) |

2.53 (64) |

2.09 (53) |

36.98 (939) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 13.3 (34) |

10.9 (28) |

5.5 (14) |

1.0 (2.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.9 (4.8) |

8.4 (21) |

41.0 (104) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.2 | 8.4 | 9.7 | 11.8 | 12.6 | 11.2 | 9.0 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 9.9 | 8.8 | 9.7 | 119.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 6.4 | 4.5 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 4.2 | 19.6 |

| Source: NOAA[26][27] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 5,107 | — | |

| 1860 | 7,822 | 53.2% | |

| 1870 | 9,880 | 26.3% | |

| 1880 | 16,031 | 62.3% | |

| 1890 | 21,014 | 31.1% | |

| 1900 | 29,102 | 38.5% | |

| 1910 | 38,002 | 30.6% | |

| 1920 | 58,593 | 54.2% | |

| 1930 | 67,542 | 15.3% | |

| 1940 | 67,195 | −0.5% | |

| 1950 | 71,193 | 5.9% | |

| 1960 | 89,144 | 25.2% | |

| 1970 | 95,162 | 6.8% | |

| 1980 | 85,725 | −9.9% | |

| 1990 | 84,298 | −1.7% | |

| 2000 | 81,855 | −2.9% | |

| 2010 | 78,860 | −3.7% | |

| 2020 | 77,816 | −1.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[28] 2020 census[29] | |||

Waves of European immigrants, including Danes, Germans, and Czechs, began to settle in Racine between the Civil War and the First World War. African Americans started arriving in large numbers during World War I, as they did in other Midwestern industrial towns, and Hispanics migrated to Racine from roughly 1925 onward.

Unitarians, Episcopalians and Congregationalists from New England initially dominated Racine's religious life. Racine's Emmaus Lutheran Church, the oldest Danish Lutheran Church in North America, was founded on August 22, 1851. Originally a founding member of the Danish American Lutheran Church, it has subsequently been a member of the United Danish Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (UDELCA), the American Lutheran Church (ALC), and, since 1988, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA). There was also a large Catholic movement to the city, opening up churches for their own ethnicity, such as St. Stanislaus (Polish), St. Rose (Irish), Holy Name (German), St. Patrick (Irish), Sacred Heart (Italian), St. Joseph (German), St. Mary (German), Holy Trinity (Slovak), St. Casimir (Lithuanian), and others. As years passed, populations moved and St. Stanislaus, Holy Name, Holy Trinity, St. Rose, and St. Casimir merged in 1998, forming St. Richard. With new waves of people arriving, older parishes received a boost from the Hispanic community, which formed Cristo Rey, re-energizing St. Patrick's into the strong Catholic community of today.

Racine has the largest Danish population in North America.[30] The city has become known for its Danish pastries, particularly kringle. Several local bakeries have been featured on the Food Network[31][32] highlighting the pastry. In June 2010, President Barack Obama stopped at an O & H Danish Bakery before hosting a town hall meeting on the economy and jobs later that afternoon.[33]

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[34] | Pop 2010[35] | Pop 2020[36] | % 2000 | % 2010 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 51,962 | 42,189 | 35,771 | 63.48% | 53.50% | 45.97% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 16,349 | 17,341 | 18,003 | 19.97% | 21.99% | 23.14% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 229 | 279 | 200 | 0.28% | 0.35% | 0.26% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 473 | 578 | 575 | 0.58% | 0.73% | 0.74% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 30 | 17 | 14 | 0.04% | 0.02% | 0.02% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 106 | 143 | 398 | 0.13% | 0.18% | 0.51% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 1,284 | 2,004 | 3,999 | 1.57% | 2.54% | 5.14% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 11,422 | 16,309 | 18,856 | 13.95% | 20.68% | 24.23% |

| Total | 81,855 | 78,860 | 77,816 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2020 census

[edit]As of the census of 2020, the city's population was 77,816, roughly a 1% decrease from its 2010 population.[37] The population density was 5,028.5 inhabitants per square mile (1,941.5/km2). There were 33,871 housing units at an average density of 2,188.8 per square mile (845.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 51.5% White, 23.9% Black or African American, 0.8% Asian, 0.7% Native American, 10.4% from other races, and 12.7% from two or more races. Ethnically, the population was 24.2% Hispanic or Latino of any race.

According to the American Community Survey estimates for 2016–2020, the median income for a household in the city was $44,346, and the median income for a family was $54,161. Male full-time workers had a median income of $42,864 versus $36,299 for female workers. The per capita income for the city was $22,837. About 15.7% of families and 20.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 29.0% of those under age 18 and 9.1% of those age 65 or over.[38] Of the population age 25 and over, 86.5% were high school graduates or higher and 17.2% had a bachelor's degree or higher.[39]

2010 census

[edit]As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 78,860 people, 30,530 households, and 19,222 families residing in the city. The population density was 5,094.3 inhabitants per square mile (1,966.9/km2). There were 33,887 housing units at an average density of 2,189.1 per square mile (845.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 58.8% White, 22.6% African American, 0.5% Native American, 0.8% Asian, 10.3% from other races, and 4.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 20.7% of the population.

There were 30,530 households, of which 35.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.5% were married couples living together, 20.1% had a female householder with no husband present, 6.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 37.0% were non-families. 30.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.53 and the average family size was 3.17.

The median age in the city was 33 years. 27.9% of residents were under the age of 18; 9.8% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 27.6% were from 25 to 44; 23.8% were from 45 to 64; and 10.9% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.8% male and 51.2% female.

- Population estimates, July 1, 2017: 77,542[40]

- Population estimates base, April 1, 2010: 78,860[40]

- Veterans, 2011–2015: 4,861[40]

- Income and poverty[40]

- Median household income for Racine (in 2015 dollars), 2011–2015: $41,455[40]

- Per capita income in past 12 months in Racine (in 2015 dollars), 2011–2015: $20,580[40]

- Poverty rate in Racine: 21.6%[40]

2023 United States Census Bureau American Community Survey one-year estimates

[edit]|

Racial Makeup of Racine (2023)[41] White alone (54.16%) Black alone (18.34%) Native American alone (0.39%) Asian alone (0.06%) Pacific Islander alone (0.06%) Some other race alone (8.04%) Two or more races (18.95%)

|

Racial Makeup of Kenosha treating Hispanics as a Racial Category (2023)[41] White NH (48.06%) Black NH (18.05%) Native American NH (0.39%) Asian NH (0.06%) Pacific Islander NH (0.06%) Other race NH (0.38%) Two or more races NH (7.03%) Hispanic Any Race (25.96%)

|

Racial Makeup of Hispanics in Kenosha (2023)[41] White alone (23.51%) Black alone (1.11%) Native American alone (0.00%) Asian alone (0.00%) Pacific Islander alone (0.00%) Other race alone (29.48%) Two or more races (45.90%)

|

Crime rates

[edit]Racine employs community-oriented policing, the systematic use of partnerships and problem-solving techniques to address the immediate conditions that give rise to crime. The number of crimes committed in the city in 2013 dropped in several categories to the lowest point in decades. Racine saw a 38.3 percent drop in violent crime from 2009 to 2013, making it the 10th largest decrease in the country. Property crimes were at their lowest point since 1965, while the number of violent crimes was the lowest for any year on record.[42][43][44]

However, that trend has since changed. As of 2018, the chance of becoming a victim of either violent or property crime in Racine is 1 in 37, thus making the city's crime rate higher than 92% of Wisconsin's other cities and towns.[45]

Arts and culture

[edit]

Racine is home to museums, theater companies, visual arts organizations, galleries, performance groups, music organizations, dance studios, concert series and special art events.[46]

The Racine Art Museum is the site of the largest collection of contemporary craft in America, with over 4,000 pieces in art jewelry, ceramics, fibers, glass, metals, polymer, and wood, and over 4,000 works on paper and sculptures.[47] RAM's satellite campus, Wustum Museum of Fine Arts, presents exhibitions of regional artists along with art classes and workshops.[48][49][50] The Racine Arts Council's exhibitions feature local and regional artists.[51] The annual 16th Street Studios Open House offers a look inside artists’ workspaces at the Racine Arts and Business Center.[52]

The Racine Theater Guild annually offers a season of seven to eight main-stage plays and musicals, Racine Children's Theatre, Jean's Jazz Series and Comedy Tonight.[53] Every winter, Over Our Head Players at 6th Street Theatre hosts Snowdance, a playwriting contest in which audience members determine the winning plays. Entries for the contest come from all over the world.[54]

The Racine Symphony Orchestra performs 2-3 Masterworks concerts per year, several free pops concerts, and an annual concert for fifth graders.[55] Local bands perform free noontime and evening concerts at downtown's centrally located Monument Square throughout the summer.[56] Weekly open mic opportunities for musicians and other performers are hosted by Family Power Music.[57]

The monthly BONK! Performance Series showcases local, regional and national poets.[58][59]

There are four opportunities for area artists and poets to receive recognition for their work: The RAM Artist Fellowship Program awards four $3,000 Artist Fellowships and one $1,500 Emerging Artist Award every two years with recipients given solo exhibits;[60][61] The Racine Arts Council ArtSeed Program provides grants ranging from $500 to $1,500 to projects that are new, innovative, experimental and collaborative;[62] the Racine Writer in Residence Program awards two 6-month residencies each year with a stipend of $1,500;[63] the Racine/Kenosha Poet Laureate Program chooses one poet from Racine and one poet from Kenosha every 2 years.[64][65]

Architecture

[edit]

Racine has several examples of Frank Lloyd Wright's work, including the Johnson Wax Headquarters, Wingspread, the Thomas P. Hardy House and the Keland House. S.C. Johnson offers free tours of its corporate campus, and receives about 9,000 visitors per year. The Research Tower, which is located on the SC Johnson campus, is one of only 2 existing high rise buildings designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.[66][67] Fortaleza Hall, designed by Norman Foster, houses the "SC Johnson Gallery: Frank Lloyd Wright At Home" and a Frank Lloyd Wright library.[68] The Johnson Wax disc-shaped Golden Rondelle Theater was originally constructed as the Johnson Wax pavilion for the 1964 New York World's Fair and then relocated to Racine.[69]

The Racine Art Museum, designed by the Chicago architecture firm Brininstool + Lynch, is a modern reuse of an existing structure to house RAM's permanent collection of contemporary craft. The building has an exterior façade of translucent acrylic panels that are illuminated at night, making the museum glow in the dark like a Japanese lantern.[70]

The OS House, a private residence designed by the Milwaukee architecture firm Johnsen Schmaling Architects, was recognized in 2011 as one of the top 10 residential projects in the United States by the American Institute of Architects.[71] The LEED Platinum-certified home was also named in 2011 as one of the top 10 green projects in the country by the AIA,[72][73][74] and in 2012 as one of 11 national winners in the Small Projects category.[75] The OS House has been featured in the New York Times.[76] The house, an example of 21st-century modern architecture, is located on the shore of Lake Michigan in Racine's south side historic district.[77]

Buildings on the National Register of Historic Places

[edit]- Hansen House

- Memorial Hall

- St. Luke's Episcopal Church, Chapel, Guildhall, and Rectory

- St. Patrick's Roman Catholic Church

- Wind Point Lighthouse

- YMCA Building

- Racine Elks Club, Lodge No. 252 (Racine, Wisconsin)

- McClurg Building (Main Place)

- Racine Depot

Government

[edit]

Racine has a mayor-council form of government. The mayor is the chief executive, elected for a term of four years. The mayor appoints commissioners and other officials who oversee the departments, subject to Common Council approval. The current mayor is Cory Mason (D); he is the 58th mayor of Racine, currently serving his second full four-year term after taking office in a special election in October 2017.

Racine's other citywide elected official is the Municipal Judge. The city council is made up of 15 aldermen, one elected from each aldermanic district in the city. The council enacts local ordinances and approves the city budget. Government priorities and activities are established in a budget ordinance usually adopted each November. Being a diverse community with a history of organized labor, the city predominantly votes for the Democratic Party. The city's youngest city council president was Tom Mortenson, 28, who was a leading Progressive Republican who led ethical reform that served as a model for other municipal governments.

For federal representation, Racine is part of Wisconsin's 1st congressional district, represented by Bryan Steil (R). Wisconsin's two U.S. senators are Ron Johnson (R) and Tammy Baldwin (D).

In Wisconsin's lower state legislative chamber, the Wisconsin State Assembly, Racine is split between the 62nd Assembly district in the north, represented by Robert Wittke (R), and the 66th Assembly district in the south, represented by Greta Neubauer (D). In Wisconsin's upper chamber, the Wisconsin Senate, the area represented by the 66th Assembly district falls within Wisconsin's 22nd Senate district, represented by Robert Wirch (D). The area represented by the 62nd Assembly district falls within the 21st Senate district, represented by Van H. Wanggaard (R).

Public safety

[edit]Fire protection and ambulance service is provided by the Racine Fire Department with six fire stations. Law enforcement services are provided by the Racine Police Department.

Education

[edit]Public schools

[edit]Racine's public schools are administered by the Racine Unified School District, which oversees one early education center, seven elementary schools, eight K-8 schools, two 6-12 schools, three high schools and one alternative education center with a combined student enrollment of around 16,000. Programs such as International Baccalaureate[78] and Montessori are utilized in the District.

Private schools

[edit]Private schools in the city include:

The Prairie School is in nearby Wind Point. It was co-founded by Imogene "Gene" Powers Johnson.[79]

Higher education

[edit]University of Wisconsin–Parkside is located south of Racine in the Town of Somers. Prior to Parkside's creation there were state college campuses in both Racine and Kenosha, but with their proximity it was decided they would be better served by one larger campus in between the two cities. A campus of Gateway Technical College, which serves the tri-county area of the southeastern corner of Wisconsin, is located in the downtown district on Lake Michigan.

Sports

[edit]The Racine Legion, a professional football team and part of the National Football League, played here from 1922 to 1924. Its official name was the Horlick-Racine Legion.[80] The team then operated as the Racine Tornadoes in 1926. They played at Horlick Field.

Prom

[edit]The city is known for its large prom celebration, at which students from all the high schools in the city participate in an after prom party. This was featured on the radio show This American Life in Episode #186 "Prom", which originally aired on June 8, 2001;[81] Racine's prom tradition was also the subject of the 2006 documentary The World's Best Prom. In addition to the large prom Racine has become known for, the city has also been hosting a special needs prom called A Night To Remember every year since 2013. The A Night To Remember prom always takes place on the Sunday following Racine's larger prom and includes those from age 13 to 30.[82]

Media

[edit]Racine is served by the daily newspaper The Journal Times,[83] which is the namesake (but not current owner) of radio station WRJN (1400), and is owned by Lee Enterprises. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel formerly published a Racine-specific page on Thursdays and a Racine County section on Sundays, but dropped them in 2007. The Insider News covers issues specific to the city's Black community. The Racine County Eye also covers Racine County news. Happenings Magazine covers local entertainment events in Racine.

The city has one television station owned by Weigel Broadcasting, WMLW-TV (Channel 49), an independent station which airs syndicated content, and had its analog transmitter just north of the Milwaukee County line in Oak Creek. For all intents and purposes, the station serves all of southeastern Wisconsin, with the station offices located in West Allis and the station's current transmitter is located on the Weigel tower in Milwaukee's Lincoln Park. WDJT-TV (its sister CBS station) continues to produce a weekend public affairs program called Racine & Me which is devoted to topics of interest to Racine residents.

FM radio stations serving the area are country music WVTY (92.1 FM) and urban contemporary WKKV-FM (100.7). WVTY specifically targets Racine and Kenosha and is locally owned (though with some competition with market leader WMIL-FM), while WKKV is a station owned by iHeartMedia that, although licensed to Racine and having a transmitter in north-central Racine County, is targeted towards Milwaukee audiences and has its offices in Greenfield. Sturtevant-licensed WDDW-FM (104.7) broadcasts a traditional Mexican music format targeting the metro area's Mexican-American population. WGTD (91.1 FM) is operated by Gateway Technical College in Kenosha. While licensed to the city of Kenosha, the station provides news coverage to the cities of Kenosha and Racine.

Infrastructure

[edit]

Water

[edit]Racine's municipal water is drawn from Lake Michigan. In 2011, the city's water was named the best tasting tap water in the United States by a panel of the U.S. Conference of Mayors.[84]

Transportation

[edit]Mass transit is provided by the Belle Urban System or "BUS" for short.[85] Taxi service is provided by Racine Taxi.[86]

Racine is also served by Amtrak's Hiawatha from the Sturtevant station in Racine County.[87] Additional train service to Chicago is provided by Metra's Union Pacific/North Line from the downtown Kenosha station, which is located 6 miles from the Racine County line and 11 miles from downtown Racine. Up until 1971, residents could catch a train in downtown Racine at the Racine Depot. Today, the equivalent route between the Kenosha and Milwaukee train stations is covered by a bus route co-provided by Racine's public transit system and Wisconsin Coach Lines.[88]

Airport

[edit]Batten International Airport (KRAC) is a public use airport located in Racine, and the largest privately owned airport in the United States. Racine is one of only three Wisconsin cities, along with Milwaukee and Green Bay, to have airports with customs intake capabilities.[89] Commercial air service is provided by O'Hare International Airport and General Mitchell International Airport.

Sister cities

[edit]Racine's sister cities are:[90]

Aalborg, Region Nordjylland, Denmark

Aalborg, Region Nordjylland, Denmark Montélimar, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France

Montélimar, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France Ōiso, Kanagawa, Japan

Ōiso, Kanagawa, Japan Zapotlanejo, Jalisco, Mexico

Zapotlanejo, Jalisco, Mexico Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil

Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil

Notable people

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Racine, Wisconsin -- A Brief History". The Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ^ "Look Up a ZIP Code". Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "Cities -". Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ "Racine, Wisconsin (WI), United States". AllRefer.com. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved April 5, 2007.

- ^ a b US Department of Commerce Economic & Statistics Administration; US Census Bureau (January 2012). "Milwaukee-Racine-Waukesha, WI Combined Statistical Area" (PDF). Census.gov. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ Denise DiFulco (August 23, 2007). "Grist for the Daily Grind". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- ^ [Racine: Growth and Change in a Wisconsin County]

- ^ "Tablet to Honor Racine's Founder at Knapp School". The Racine Journal-Times. February 13, 1936. p. 4. Retrieved August 14, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Rosenberry, Lois Kimball Mathews. The Expansion of New England: The Spread of New England Settlement and Institutions to the Mississippi River, 1620-1865,

- ^ "Wisconsinhistory.org". Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ "Racine High School | Racine History". www.vindustries.com. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ Rogan, Adam (July 3, 2020). "The story of Joshua Glover and how Racine freed him from slavery in 1854". Racine Journal Times. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- ^ Clymer, Floyd. Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877–1925 (New York: Bonanza Books, 1950), p.2 & 153.

- ^ It had no less than two 4.75 hp (3.5 kW) engines. Clymer, p.6.

- ^ "Pennington". Grace's Guide to British Industrial History. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ^ Before 1926. Clymer, p.36.

- ^ Also before 1926. Clymer, p.153.

- ^ James R. Hagerty, Disposal Maker Gives China a Whirl, The Wall Street Journal, March 27, 2014, p. B6.

- ^ Lee Roberts, ‘’Be a tourist in Racine County’’, Racine Journal Times, January 31, 2013.

- ^ "2020 Gazetteer Files". census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Racine, WI". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/racinecitywisconsin,US/PST045219 [dead link]

- ^ The Bridge

- ^ "Road Tasted". FoodNetwork.com. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2007.

- ^ "Food Finds". FoodNetwork.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2007.

- ^ Don Walker, "Obama brakes for a bite at Racine kringle bakery" Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 1, 2010.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Racine city, Wisconsin". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Racine city, Wisconsin". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Racine city, Wisconsin". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "2020 Decennial Census: Racine city, Wisconsin". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics, 2020 American Community Survey: Racine city, Wisconsin". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ "Selected Social Characteristics, 2020 American Community Survey: Racine city, Wisconsin". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Census.gov". Census.gov. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ a b c "B03002 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – Racine, Wisconsin – 2023 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. July 1, 2023. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ Aaron Knapp, "Fewest violent crimes on record in 2013", Racine Journal Times, February 4, 2014.

- ^ The Journal Times Editorial Board, "Friday Finishers: Good news on crime", Racine Journal Times, February 7, 2014.

- ^ Heather Asiyanbi, "City Robberies, Property Crime, Homicide Lowest in Decades", Racine County Eye, February 4, 2012. Archived April 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Racine, WI Crime Rates and Statistics - NeighborhoodScout". www.neighborhoodscout.com. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ Mary Billard, On Lake Michigan, a Port of Call for Art, The New York Times, November 30, 2007.

- ^ Rafael Francisco Salas,"Magic Mud at Racine Art Museum a must during NCECA", Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, March 20, 2014.

- ^ Peggy Sue Dunigan, Wustum Museum Highlights Wisconsin Photography, Express Milwaukee, August 20, 2012.

- ^ Lee Roberts, Learn something new: Local Continuing Education Opportunities Abound, Racine Journal Times, February 23, 2011.

- ^ Wustum Studio Art Program, Racine Art Museum.

- ^ Lee Roberts, "Scene & Heard: Racine County potters play with fire for ArtSpace show", Racine Journal Times, March 20, 2014.

- ^ Liz Snyder, "WATCH NOW: Racine's 16th Street Studios hosting open house, art market", Kenosha News, December 1, 2022.

- ^ Lee Roberts, Local theater groups ready to take the stage, Racine Journal Times, September 12, 2013.

- ^ Jessica Tuttle, "Laughs by the minute: Racine’s Sixth Street Theatre site of annual Snowdance 10-Minute Comedy Festival", Kenosha News, January 30, 2014.

- ^ Lee Roberts, Trio of upcoming RSO concerts feature music for a lifetime, Racine Journal Times, March 13, 2014.

- ^ Lee Roberts, "Free outdoor concerts abound this summer", Racine Journal Times, May 30, 2013.

- ^ "Live Music by Family Power Music with Bryan Cherry", Racine Journal Times, September 27, 2013.

- ^ Lee Roberts, "BONK! series to present its 65th show", Racine Journal Times, February 13, 2014.

- ^ The Library as Incubator Project, BONK! Performance Series at Racine Public Library[usurped], February 8, 2013.

- ^ Lee Roberts, RAM Artist Fellowship exhibit at Wustum spotlights work of four local artists, Racine Journal Times, October 31, 2013.

- ^ "Winners of the 2020 Racine Art Museum Artist Fellowship named", Racine Journal Times, April 15, 2020.

- ^ Lee Roberts, Grant program seeks to expand local arts scene, Racine Journal Times, March 23, 2013.

- ^ "Mauer is new Racine Writer-in-Residence", Racine Journal Times, January 22, 2020.

- ^ Lee Roberts, A passion for poetry: Racine’s first co-poets laureate want to enlighten, entertain, Racine Journal Times, May 21, 2011.

- ^ Poets Laureate for Racine and Kenosha to be announced at Oct. 25 event, Racine Journal Times, October 24, 2013.

- ^ Robert Sharoff, "A Corporate Paean to Frank Lloyd Wright", The New York Times, April 29, 2014.

- ^ Blair Kamin, "Frank Lloyd Wright's tower worthy of debate, and a trip", Chicago Tribune, April 23, 2014.

- ^ Blair Kamin, "Frank Lloyd Wright's legacy lifts off anew: Norman Foster's Fortaleza Hall an update of iconic S.C. Johnson campus in Racine, Wis.", Chicago Tribune, January 28, 2010.

- ^ Bill Cotter, Bill Young, The 1964–1965 New York World's Fair: Creation and Legacy, Arcadia Publishing, 2008, p. 90.

- ^ Philip Berger, "Racine Art Museum aims high", Chicago Tribune, April 20, 2003.

- ^ Craig Nakano, "AIA names housing design award winners for 2011", Los Angeles Times, March 19, 2011.

- ^ Katie Weeks, "AIA COTE 2011 Top Ten Green Projects: OS House: A single-family residence in Racine, Wisc., designed by Johnsen Schmaling Architects:, Architect: The Magazine of the American Institute of Architects, April 12, 2011.

- ^ Mary Louise Schumacher, "Two of nation's top 10 green buildings in Wisconsin", Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 14, 2011.

- ^ "Photos: OS House in Racine is one of Wisconsin's greenest homes", Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, September 25, 2010.

- ^ Karissa Rosenfield, "AIA selects the 2012 Recipients of the Small Project Awards", ArchDaily, July 31, 2012.

- ^ Fred Bernstein, "A Box of Fresh Air", The New York Times, August 25, 2010.

- ^ David Steinkraus, "Modern squared: Main Street house boasts both modern architecture and green technologies", Racine Journal Times, August 27, 2010.

- ^ "About Racine Unified School District | RUSD". October 29, 2019.

- ^ Burke, Michael (March 4, 2018). "'Gene' Johnson, widow of the late Sam Johnson, dies". The Journal Times. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ Snyder, Matthew (November 19, 2014). Welcome To Horlickville! (First ed.). Matthew C. Snyder publishing. p. 1. ISBN 9781634523684. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ "This American Life". ThisLife.org. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ^ Rogan, Adam. "Special-needs prom, now in its sixth year, transitions into new era". Journal Times. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- ^ Times, Journal. "journaltimes.com | Read Racine, WI and Wisconsin breaking news. Get latest news, events and information on Wisconsin sports, weather, entertainment and lifestyles". Journal Times. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ "Racine's water hailed as best tasting, city wins $15,000", Racine Journal Times, June 20, 2011.

- ^ "City of Racine". Racine Transit. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- ^ Michael Burke, "Racine Taxi open for business", Racine Journal Times, October 7, 2013.

- ^ Lydia Mulvany, "Amtrak's Hiawatha route tops monthly ridership record", Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, August 15, 2013

- ^ "Kenosha-Racine-Milwaukee schedule" (PDF). Wisconsin Coach Lines. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

- ^ Michael Burke, "Batten to build — New space would be for Customs clearances on international flights", Racine Journal Times, November 16, 2013

- ^ "Our Sister Cities". Racine's Sister Cities Planning Committee. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

External links

[edit]- City of Racine Archived September 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Racine County Convention and Visitors Bureau

- Beach, Chandler B., ed. (1914). . . Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.

- Racine Writer in Residence Project