Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse | |

|---|---|

Ἀρχιμήδης | |

Archimedes Thoughtful by Domenico Fetti (1620) | |

| Born | c. 287 BC |

| Died | c. 212 BC (aged approximately 75) Syracuse, Sicily |

| Known for | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics Physics Astronomy Mechanics Engineering |

Archimedes of Syracuse[a] (/ˌɑːrkɪˈmiːdiːz/ AR-kim-EE-deez;[2] c. 287 – c. 212 BC) was an Ancient Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily.[3] Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientists in classical antiquity. Regarded as the greatest mathematician of ancient history, and one of the greatest of all time,[4] Archimedes anticipated modern calculus and analysis by applying the concept of the infinitely small and the method of exhaustion to derive and rigorously prove a range of geometrical theorems.[5][6][7] These include the area of a circle, the surface area and volume of a sphere, the area of an ellipse, the area under a parabola, the volume of a segment of a paraboloid of revolution, the volume of a segment of a hyperboloid of revolution, and the area of a spiral.[8][9]

Archimedes' other mathematical achievements include deriving an approximation of pi (π), defining and investigating the Archimedean spiral, and devising a system using exponentiation for expressing very large numbers. He was also one of the first to apply mathematics to physical phenomena, working on statics and hydrostatics. Archimedes' achievements in this area include a proof of the law of the lever,[10] the widespread use of the concept of center of gravity,[11] and the enunciation of the law of buoyancy known as Archimedes' principle.[12] He is also credited with designing innovative machines, such as his screw pump, compound pulleys, and defensive war machines to protect his native Syracuse from invasion.

Archimedes died during the siege of Syracuse, when he was killed by a Roman soldier despite orders that he should not be harmed. Cicero describes visiting Archimedes' tomb, which was surmounted by a sphere and a cylinder that Archimedes requested be placed there to represent his most valued mathematical discovery.

Unlike his inventions, Archimedes' mathematical writings were little known in antiquity. Alexandrian mathematicians read and quoted him, but the first comprehensive compilation was not made until c. 530 AD by Isidore of Miletus in Byzantine Constantinople, while Eutocius' commentaries on Archimedes' works in the same century opened them to wider readership for the first time. The relatively few copies of Archimedes' written work that survived through the Middle Ages were an influential source of ideas for scientists during the Renaissance and again in the 17th century,[13][14] while the discovery in 1906 of previously lost works by Archimedes in the Archimedes Palimpsest has provided new insights into how he obtained mathematical results.[15][16][17][18]

Biography

Early life

Archimedes was born c. 287 BC in the seaport city of Syracuse, Sicily, at that time a self-governing colony in Magna Graecia. The date of birth is based on a statement by the Byzantine Greek scholar John Tzetzes that Archimedes lived for 75 years before his death in 212 BC.[9] Plutarch wrote in his Parallel Lives that Archimedes was related to King Hiero II, the ruler of Syracuse, although Cicero suggests he was of humble origin.[19][20] In the Sand-Reckoner, Archimedes gives his father's name as Phidias, an astronomer about whom nothing else is known.[20][21] A biography of Archimedes was written by his friend Heracleides, but this work has been lost, leaving the details of his life obscure. It is unknown, for instance, whether he ever married or had children, or if he ever visited Alexandria, Egypt, during his youth.[22] From his surviving written works, it is clear that he maintained collegial relations with scholars based there, including his friend Conon of Samos and the head librarian Eratosthenes of Cyrene.[b]

Career

The standard versions of Archimedes' life were written long after his death by Greek and Roman historians. The earliest reference to Archimedes occurs in The Histories by Polybius (c. 200–118 BC), written about 70 years after his death.[20] It sheds little light on Archimedes as a person, and focuses on the war machines that he is said to have built in order to defend the city from the Romans.[23] Polybius remarks how, during the Second Punic War, Syracuse switched allegiances from Rome to Carthage, resulting in a military campaign under the command of Marcus Claudius Marcellus and Appius Claudius Pulcher, who besieged the city from 213 to 212 BC. He notes that the Romans underestimated Syracuse's defenses, and mentions several machines Archimedes designed, including improved catapults, crane-like machines that could be swung around in an arc, and other stone-throwers. Although the Romans ultimately captured the city, they suffered considerable losses due to Archimedes' inventiveness.[24]

Cicero (106–43 BC) mentions Archimedes in some of his works.[20] While serving as a quaestor in Sicily, Cicero found what was presumed to be Archimedes' tomb near the Agrigentine gate in Syracuse, in a neglected condition and overgrown with bushes.[9][25] Cicero had the tomb cleaned up and was able to see the carving and read some of the verses that had been added as an inscription. The tomb carried a sculpture illustrating Archimedes' favorite mathematical proof, that the volume and surface area of the sphere are two-thirds that of an enclosing cylinder including its bases.[26][27] He also mentions that Marcellus brought to Rome two planetariums Archimedes built.[28] The Roman historian Livy (59 BC–17 AD) retells Polybius's story of the capture of Syracuse and Archimedes' role in it.[23]

Death

Plutarch (45–119 AD) provides at least two accounts on how Archimedes died after Syracuse was taken.[20] According to the most popular account, Archimedes was contemplating a mathematical diagram when the city was captured. A Roman soldier commanded him to come and meet Marcellus, but he declined, saying that he had to finish working on the problem. This enraged the soldier, who killed Archimedes with his sword. Another story has Archimedes carrying mathematical instruments before being killed because a soldier thought they were valuable items. Marcellus was reportedly angered by Archimedes' death, as he considered him a valuable scientific asset (he called Archimedes "a geometrical Briareus") and had ordered that he should not be harmed.[30][31]

The last words attributed to Archimedes are "Do not disturb my circles" (Latin, "Noli turbare circulos meos"; Katharevousa Greek, "μὴ μου τοὺς κύκλους τάραττε"), a reference to the mathematical drawing that he was supposedly studying when disturbed by the Roman soldier.[20] There is no reliable evidence that Archimedes uttered these words and they do not appear in Plutarch's account. A similar quotation is found in the work of Valerius Maximus (fl. 30 AD), who wrote in Memorable Doings and Sayings, "... sed protecto manibus puluere 'noli' inquit, 'obsecro, istum disturbare'" ("... but protecting the dust with his hands, said 'I beg of you, do not disturb this'").[23]

Discoveries and inventions

Archimedes' principle

The most widely known anecdote about Archimedes tells of how he invented a method for determining the volume of an object with an irregular shape. According to Vitruvius, a crown for a temple had been made for King Hiero II of Syracuse, who supplied the pure gold to be used. The crown was likely made in the shape of a votive wreath.[32] Archimedes was asked to determine whether some silver had been substituted by the goldsmith without damaging the crown, so he could not melt it down into a regularly shaped body in order to calculate its density.[33]

In this account, Archimedes noticed while taking a bath that the level of the water in the tub rose as he got in, and realized that this effect could be used to determine the golden crown's volume. Archimedes was so excited by this discovery that he took to the streets naked, having forgotten to dress, crying "Eureka!" (Greek: "εὕρηκα, heúrēka!, lit. 'I have found [it]!'). For practical purposes water is incompressible,[34] so the submerged crown would displace an amount of water equal to its own volume. By dividing the mass of the crown by the volume of water displaced, its density could be obtained; if cheaper and less dense metals had been added, the density would be lower than that of gold. Archimedes found that this is what had happened, proving that silver had been mixed in.[32][33]

The story of the golden crown does not appear anywhere in Archimedes' known works. The practicality of the method described has been called into question due to the extreme accuracy that would be required to measure water displacement.[35] Archimedes may have instead sought a solution that applied the hydrostatics principle known as Archimedes' principle, found in his treatise On Floating Bodies: a body immersed in a fluid experiences a buoyant force equal to the weight of the fluid it displaces.[36] Using this principle, it would have been possible to compare the density of the crown to that of pure gold by balancing it on a scale with a pure gold reference sample of the same weight, then immersing the apparatus in water. The difference in density between the two samples would cause the scale to tip accordingly.[12] Galileo Galilei, who invented a hydrostatic balance in 1586 inspired by Archimedes' work, considered it "probable that this method is the same that Archimedes followed, since, besides being very accurate, it is based on demonstrations found by Archimedes himself."[37][38]

Law of the lever

While Archimedes did not invent the lever, he gave a mathematical proof of the principle involved in his work On the Equilibrium of Planes.[39] Earlier descriptions of the principle of the lever are found in a work by Euclid and in the Mechanical Problems, belonging to the Peripatetic school of the followers of Aristotle, the authorship of which has been attributed by some to Archytas.[40][41]

There are several, often conflicting, reports regarding Archimedes' feats using the lever to lift very heavy objects. Plutarch describes how Archimedes designed block-and-tackle pulley systems, allowing sailors to use the principle of leverage to lift objects that would otherwise have been too heavy to move.[42] According to Pappus of Alexandria, Archimedes' work on levers and his understanding of mechanical advantage caused him to remark: "Give me a place to stand on, and I will move the Earth" (Greek: δῶς μοι πᾶ στῶ καὶ τὰν γᾶν κινάσω).[43] Olympiodorus later attributed the same boast to Archimedes' invention of the baroulkos, a kind of windlass, rather than the lever.[44]

Archimedes' screw

A large part of Archimedes' work in engineering probably arose from fulfilling the needs of his home city of Syracuse. Athenaeus of Naucratis quotes a certain Moschion in a description on how King Hiero II commissioned the design of a huge ship, the Syracusia, which could be used for luxury travel, carrying supplies, and as a display of naval power.[45] The Syracusia is said to have been the largest ship built in classical antiquity and, according to Moschion's account, it was launched by Archimedes.[44] The ship presumably was capable of carrying 600 people and included garden decorations, a gymnasium, and a temple dedicated to the goddess Aphrodite among its facilities.[46] The account also mentions that, in order to remove any potential water leaking through the hull, a device with a revolving screw-shaped blade inside a cylinder was designed by Archimedes.

Archimedes' screw was turned by hand, and could also be used to transfer water from a low-lying body of water into irrigation canals. The screw is still in use today for pumping liquids and granulated solids such as coal and grain. Described by Vitruvius, Archimedes' device may have been an improvement on a screw pump that was used to irrigate the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.[47][48] The world's first seagoing steamship with a screw propeller was the SS Archimedes, which was launched in 1839 and named in honor of Archimedes and his work on the screw.[49]

Archimedes' claw

Archimedes is said to have designed a claw as a weapon to defend the city of Syracuse. Also known as "the ship shaker", the claw consisted of a crane-like arm from which a large metal grappling hook was suspended. When the claw was dropped onto an attacking ship the arm would swing upwards, lifting the ship out of the water and possibly sinking it.[50] There have been modern experiments to test the feasibility of the claw, and in 2005 a television documentary entitled Superweapons of the Ancient World built a version of the claw and concluded that it was a workable device.[51]

Archimedes has also been credited with improving the power and accuracy of the catapult, and with inventing the odometer during the First Punic War. The odometer was described as a cart with a gear mechanism that dropped a ball into a container after each mile traveled.[52]

Heat ray

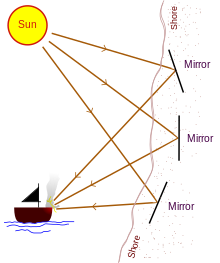

As legend has it, Archimedes arranged mirrors as a parabolic reflector to burn ships attacking Syracuse using focused sunlight. While there is no extant contemporary evidence of this feat and modern scholars believe it did not happen, Archimedes may have written a work on mirrors entitled Catoptrica,[c] and Lucian and Galen, writing in the second century AD, mentioned that during the siege of Syracuse Archimedes had burned enemy ships. Nearly four hundred years later, Anthemius, despite skepticism, tried to reconstruct Archimedes' hypothetical reflector geometry.[53]

The purported device, sometimes called "Archimedes' heat ray", has been the subject of an ongoing debate about its credibility since the Renaissance.[54] René Descartes rejected it as false, while modern researchers have attempted to recreate the effect using only the means that would have been available to Archimedes, mostly with negative results.[55][56] It has been suggested that a large array of highly polished bronze or copper shields acting as mirrors could have been employed to focus sunlight onto a ship, but the overall effect would have been blinding, dazzling, or distracting the crew of the ship rather than fire.[57] Using modern materials and larger scale, sunlight-concentrating solar furnaces can reach very high temperatures, and are sometimes used for generating electricity.[58]

Astronomical instruments

Archimedes discusses astronomical measurements of the Earth, Sun, and Moon, as well as Aristarchus' heliocentric model of the universe, in the Sand-Reckoner. Without the use of either trigonometry or a table of chords, Archimedes determines the Sun's apparent diameter by first describing the procedure and instrument used to make observations (a straight rod with pegs or grooves),[59][60] applying correction factors to these measurements, and finally giving the result in the form of upper and lower bounds to account for observational error.[21] Ptolemy, quoting Hipparchus, also references Archimedes' solstice observations in the Almagest. This would make Archimedes the first known Greek to have recorded multiple solstice dates and times in successive years.[22]

Cicero's De re publica portrays a fictional conversation taking place in 129 BC. After the capture of Syracuse in the Second Punic War, Marcellus is said to have taken back to Rome two mechanisms which were constructed by Archimedes and which showed the motion of the Sun, Moon and five planets. Cicero also mentions similar mechanisms designed by Thales of Miletus and Eudoxus of Cnidus. The dialogue says that Marcellus kept one of the devices as his only personal loot from Syracuse, and donated the other to the Temple of Virtue in Rome. Marcellus's mechanism was demonstrated, according to Cicero, by Gaius Sulpicius Gallus to Lucius Furius Philus, who described it thus:[61][62]

Hanc sphaeram Gallus cum moveret, fiebat ut soli luna totidem conversionibus in aere illo quot diebus in ipso caelo succederet, ex quo et in caelo sphaera solis fieret eadem illa defectio, et incideret luna tum in eam metam quae esset umbra terrae, cum sol e regione.

When Gallus moved the globe, it happened that the Moon followed the Sun by as many turns on that bronze contrivance as in the sky itself, from which also in the sky the Sun's globe became to have that same eclipse, and the Moon came then to that position which was its shadow on the Earth when the Sun was in line.

This is a description of a small planetarium. Pappus of Alexandria reports on a now lost treatise by Archimedes dealing with the construction of these mechanisms entitled On Sphere-Making.[28][63] Modern research in this area has been focused on the Antikythera mechanism, another device built c. 100 BC probably designed with a similar purpose.[64] Constructing mechanisms of this kind would have required a sophisticated knowledge of differential gearing.[65] This was once thought to have been beyond the range of the technology available in ancient times, but the discovery of the Antikythera mechanism in 1902 has confirmed that devices of this kind were known to the ancient Greeks.[66][67]

Mathematics

While he is often regarded as a designer of mechanical devices, Archimedes also made contributions to the field of mathematics. Plutarch wrote that Archimedes "placed his whole affection and ambition in those purer speculations where there can be no reference to the vulgar needs of life",[30] though some scholars believe this may be a mischaracterization.[68][69][70]

Method of exhaustion

Archimedes was able to use indivisibles (a precursor to infinitesimals) in a way that is similar to modern integral calculus.[6] Through proof by contradiction (reductio ad absurdum), he could give answers to problems to an arbitrary degree of accuracy, while specifying the limits within which the answer lay. This technique is known as the method of exhaustion, and he employed it to approximate the areas of figures and the value of π.

In Measurement of a Circle, he did this by drawing a larger regular hexagon outside a circle then a smaller regular hexagon inside the circle, and progressively doubling the number of sides of each regular polygon, calculating the length of a side of each polygon at each step. As the number of sides increases, it becomes a more accurate approximation of a circle. After four such steps, when the polygons had 96 sides each, he was able to determine that the value of π lay between 31/7 (approx. 3.1429) and 310/71 (approx. 3.1408), consistent with its actual value of approximately 3.1416.[71] He also proved that the area of a circle was equal to π multiplied by the square of the radius of the circle ().

Archimedean property

In On the Sphere and Cylinder, Archimedes postulates that any magnitude when added to itself enough times will exceed any given magnitude. Today this is known as the Archimedean property of real numbers.[72]

Archimedes gives the value of the square root of 3 as lying between 265/153 (approximately 1.7320261) and 1351/780 (approximately 1.7320512) in Measurement of a Circle. The actual value is approximately 1.7320508, making this a very accurate estimate. He introduced this result without offering any explanation of how he had obtained it. This aspect of the work of Archimedes caused John Wallis to remark that he was: "as it were of set purpose to have covered up the traces of his investigation as if he had grudged posterity the secret of his method of inquiry while he wished to extort from them assent to his results."[73] It is possible that he used an iterative procedure to calculate these values.[74][75]

The infinite series

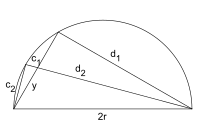

In Quadrature of the Parabola, Archimedes proved that the area enclosed by a parabola and a straight line is 4/3 times the area of a corresponding inscribed triangle as shown in the figure at right. He expressed the solution to the problem as an infinite geometric series with the common ratio 1/4:

If the first term in this series is the area of the triangle, then the second is the sum of the areas of two triangles whose bases are the two smaller secant lines, and whose third vertex is where the line that is parallel to the parabola's axis and that passes through the midpoint of the base intersects the parabola, and so on. This proof uses a variation of the series 1/4 + 1/16 + 1/64 + 1/256 + · · · which sums to 1/3.

Myriad of myriads

In The Sand Reckoner, Archimedes set out to calculate a number that was greater than the grains of sand needed to fill the universe. In doing so, he challenged the notion that the number of grains of sand was too large to be counted. He wrote:

There are some, King Gelo, who think that the number of the sand is infinite in multitude; and I mean by the sand not only that which exists about Syracuse and the rest of Sicily but also that which is found in every region whether inhabited or uninhabited.

To solve the problem, Archimedes devised a system of counting based on the myriad. The word itself derives from the Greek μυριάς, murias, for the number 10,000. He proposed a number system using powers of a myriad of myriads (100 million, i.e., 10,000 x 10,000) and concluded that the number of grains of sand required to fill the universe would be 8 vigintillion, or 8×1063.[76]

Writings

The works of Archimedes were written in Doric Greek, the dialect of ancient Syracuse.[77] Many written works by Archimedes have not survived or are only extant in heavily edited fragments; at least seven of his treatises are known to have existed due to references made by other authors.[9] Pappus of Alexandria mentions On Sphere-Making and another work on polyhedra, while Theon of Alexandria quotes a remark about refraction from the now-lost Catoptrica.[c]

Archimedes made his work known through correspondence with mathematicians in Alexandria. The writings of Archimedes were first collected by the Byzantine Greek architect Isidore of Miletus (c. 530 AD), while commentaries on the works of Archimedes written by Eutocius in the same century helped bring his work to a wider audience. Archimedes' work was translated into Arabic by Thābit ibn Qurra (836–901 AD), and into Latin via Arabic by Gerard of Cremona (c. 1114–1187). Direct Greek to Latin translations were later done by William of Moerbeke (c. 1215–1286) and Iacobus Cremonensis (c. 1400–1453).[78][79]

During the Renaissance, the Editio princeps (First Edition) was published in Basel in 1544 by Johann Herwagen with the works of Archimedes in Greek and Latin.[80]

Surviving works

The following are ordered chronologically based on new terminological and historical criteria set by Knorr (1978) and Sato (1986).[81][82]

Measurement of a Circle

This is a short work consisting of three propositions. It is written in the form of a correspondence with Dositheus of Pelusium, who was a student of Conon of Samos. In Proposition II, Archimedes gives an approximation of the value of pi (π), showing that it is greater than 223/71 (3.1408...) and less than 22/7 (3.1428...).

The Sand Reckoner

In this treatise, also known as Psammites, Archimedes finds a number that is greater than the grains of sand needed to fill the universe. This book mentions the heliocentric theory of the solar system proposed by Aristarchus of Samos, as well as contemporary ideas about the size of the Earth and the distance between various celestial bodies. By using a system of numbers based on powers of the myriad, Archimedes concludes that the number of grains of sand required to fill the universe is 8×1063 in modern notation. The introductory letter states that Archimedes' father was an astronomer named Phidias. The Sand Reckoner is the only surviving work in which Archimedes discusses his views on astronomy.[83]

On the Equilibrium of Planes

There are two books to On the Equilibrium of Planes: the first contains seven postulates and fifteen propositions, while the second book contains ten propositions. In the first book, Archimedes proves the law of the lever, which states that:

Magnitudes are in equilibrium at distances reciprocally proportional to their weights.

Archimedes uses the principles derived to calculate the areas and centers of gravity of various geometric figures including triangles, parallelograms and parabolas.[84]

Quadrature of the Parabola

In this work of 24 propositions addressed to Dositheus, Archimedes proves by two methods that the area enclosed by a parabola and a straight line is 4/3 the area of a triangle with equal base and height. He achieves this in one of his proofs by calculating the value of a geometric series that sums to infinity with the ratio 1/4.

On the Sphere and Cylinder

In this two-volume treatise addressed to Dositheus, Archimedes obtains the result of which he was most proud, namely the relationship between a sphere and a circumscribed cylinder of the same height and diameter. The volume is 4/3πr3 for the sphere, and 2πr3 for the cylinder. The surface area is 4πr2 for the sphere, and 6πr2 for the cylinder (including its two bases), where r is the radius of the sphere and cylinder.

On Spirals

This work of 28 propositions is also addressed to Dositheus. The treatise defines what is now called the Archimedean spiral. It is the locus of points corresponding to the locations over time of a point moving away from a fixed point with a constant speed along a line which rotates with constant angular velocity. Equivalently, in modern polar coordinates (r, θ), it can be described by the equation with real numbers a and b.

This is an early example of a mechanical curve (a curve traced by a moving point) considered by a Greek mathematician.

On Conoids and Spheroids

This is a work in 32 propositions addressed to Dositheus. In this treatise Archimedes calculates the areas and volumes of sections of cones, spheres, and paraboloids.

On Floating Bodies

There are two books of On Floating Bodies. In the first book, Archimedes spells out the law of equilibrium of fluids and proves that water will adopt a spherical form around a center of gravity. This may have been an attempt at explaining the theory of contemporary Greek astronomers such as Eratosthenes that the Earth is round. The fluids described by Archimedes are not self-gravitating since he assumes the existence of a point towards which all things fall in order to derive the spherical shape. Archimedes principle of buoyancy is given in this work, stated as follows:[12][85]

Any body wholly or partially immersed in fluid experiences an upthrust equal to, but opposite in direction to, the weight of the fluid displaced.

In the second part, he calculates the equilibrium positions of sections of paraboloids. This was probably an idealization of the shapes of ships' hulls. Some of his sections float with the base under water and the summit above water, similar to the way that icebergs float.[86]

Ostomachion

Also known as Loculus of Archimedes or Archimedes' Box,[87] this is a dissection puzzle similar to a Tangram, and the treatise describing it was found in more complete form in the Archimedes Palimpsest. Archimedes calculates the areas of the 14 pieces which can be assembled to form a square. Reviel Netz of Stanford University argued in 2003 that Archimedes was attempting to determine how many ways the pieces could be assembled into the shape of a square. Netz calculates that the pieces can be made into a square 17,152 ways.[88] The number of arrangements is 536 when solutions that are equivalent by rotation and reflection are excluded.[89] The puzzle represents an example of an early problem in combinatorics.

The origin of the puzzle's name is unclear, and it has been suggested that it is taken from the Ancient Greek word for "throat" or "gullet", stomachos (στόμαχος).[90] Ausonius calls the puzzle Ostomachion, a Greek compound word formed from the roots of osteon (ὀστέον, 'bone') and machē (μάχη, 'fight').[87]

The cattle problem

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing discovered this work in a Greek manuscript consisting of a 44-line poem in the Herzog August Library in Wolfenbüttel, Germany in 1773. It is addressed to Eratosthenes and the mathematicians in Alexandria. Archimedes challenges them to count the numbers of cattle in the Herd of the Sun by solving a number of simultaneous Diophantine equations. There is a more difficult version of the problem in which some of the answers are required to be square numbers. A. Amthor first solved this version of the problem[91] in 1880, and the answer is a very large number, approximately 7.760271×10206544.[92]

The Method of Mechanical Theorems

This treatise was thought lost until the discovery of the Archimedes Palimpsest in 1906. In this work Archimedes uses indivisibles,[6][7] and shows how breaking up a figure into an infinite number of infinitely small parts can be used to determine its area or volume. He may have considered this method lacking in formal rigor, so he also used the method of exhaustion to derive the results. As with The Cattle Problem, The Method of Mechanical Theorems was written in the form of a letter to Eratosthenes in Alexandria.

Apocryphal works

Archimedes' Book of Lemmas or Liber Assumptorum is a treatise with 15 propositions on the nature of circles. The earliest known copy of the text is in Arabic. T. L. Heath and Marshall Clagett argued that it cannot have been written by Archimedes in its current form, since it quotes Archimedes, suggesting modification by another author. The Lemmas may be based on an earlier work by Archimedes that is now lost.[93]

It has also been claimed that the formula for calculating the area of a triangle from the length of its sides was known to Archimedes,[d] though its first appearance is in the work of Heron of Alexandria in the 1st century AD.[94] Other questionable attributions to Archimedes' work include the Latin poem Carmen de ponderibus et mensuris (4th or 5th century), which describes the use of a hydrostatic balance, to solve the problem of the crown, and the 12th-century text Mappae clavicula, which contains instructions on how to perform assaying of metals by calculating their specific gravities.[95][96]

Archimedes Palimpsest

The foremost document containing Archimedes' work is the Archimedes Palimpsest. In 1906, the Danish professor Johan Ludvig Heiberg visited Constantinople to examine a 174-page goatskin parchment of prayers, written in the 13th century, after reading a short transcription published seven years earlier by Papadopoulos-Kerameus.[97][98] He confirmed that it was indeed a palimpsest, a document with text that had been written over an erased older work. Palimpsests were created by scraping the ink from existing works and reusing them, a common practice in the Middle Ages, as vellum was expensive. The older works in the palimpsest were identified by scholars as 10th-century copies of previously lost treatises by Archimedes.[97][99] The parchment spent hundreds of years in a monastery library in Constantinople before being sold to a private collector in the 1920s. On 29 October 1998, it was sold at auction to an anonymous buyer for a total of $2.2 million.[100][101]

The palimpsest holds seven treatises, including the only surviving copy of On Floating Bodies in the original Greek. It is the only known source of The Method of Mechanical Theorems, referred to by Suidas and thought to have been lost forever. Stomachion was also discovered in the palimpsest, with a more complete analysis of the puzzle than had been found in previous texts. The palimpsest was stored at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland, where it was subjected to a range of modern tests including the use of ultraviolet and X-ray light to read the overwritten text.[102] It has since returned to its anonymous owner.[103][104]

The treatises in the Archimedes Palimpsest include:

- On the Equilibrium of Planes

- On Spirals

- Measurement of a Circle

- On the Sphere and Cylinder

- On Floating Bodies

- The Method of Mechanical Theorems

- Stomachion

- Speeches by the 4th century BC politician Hypereides

- A commentary on Aristotle's Categories

- Other works

Legacy

Sometimes called the father of mathematics and mathematical physics, Archimedes had a wide influence on mathematics and science.[105]

Mathematics and physics

Historians of science and mathematics almost universally agree that Archimedes was the finest mathematician from antiquity. Eric Temple Bell, for instance, wrote:

Any list of the three "greatest" mathematicians of all history would include the name of Archimedes. The other two usually associated with him are Newton and Gauss. Some, considering the relative wealth—or poverty—of mathematics and physical science in the respective ages in which these giants lived, and estimating their achievements against the background of their times, would put Archimedes first.[106]

Likewise, Alfred North Whitehead and George F. Simmons said of Archimedes:

... in the year 1500 Europe knew less than Archimedes who died in the year 212 BC ...[107]

If we consider what all other men accomplished in mathematics and physics, on every continent and in every civilization, from the beginning of time down to the seventeenth century in Western Europe, the achievements of Archimedes outweighs it all. He was a great civilization all by himself.[108]

Reviel Netz, Suppes Professor in Greek Mathematics and Astronomy at Stanford University and an expert in Archimedes notes:

And so, since Archimedes led more than anyone else to the formation of the calculus and since he was the pioneer of the application of mathematics to the physical world, it turns out that Western science is but a series of footnotes to Archimedes. Thus, it turns out that Archimedes is the most important scientist who ever lived.[109]

Leonardo da Vinci repeatedly expressed admiration for Archimedes, and attributed his invention Architonnerre to Archimedes.[110][111][112] Galileo called him "superhuman" and "my master",[113][114] while Huygens said, "I think Archimedes is comparable to no one", consciously emulating him in his early work.[115] Leibniz said, "He who understands Archimedes and Apollonius will admire less the achievements of the foremost men of later times".[116] Gauss's heroes were Archimedes and Newton,[117] and Moritz Cantor, who studied under Gauss in the University of Göttingen, reported that he once remarked in conversation that "there had been only three epoch-making mathematicians: Archimedes, Newton, and Eisenstein".[118]

The inventor Nikola Tesla praised him, saying:

Archimedes was my ideal. I admired the works of artists, but to my mind, they were only shadows and semblances. The inventor, I thought, gives to the world creations which are palpable, which live and work.[119]

Honors and commemorations

There is a crater on the Moon named Archimedes (29°42′N 4°00′W / 29.7°N 4.0°W) in his honor, as well as a lunar mountain range, the Montes Archimedes (25°18′N 4°36′W / 25.3°N 4.6°W).[120]

The Fields Medal for outstanding achievement in mathematics carries a portrait of Archimedes, along with a carving illustrating his proof on the sphere and the cylinder. The inscription around the head of Archimedes is a quote attributed to 1st century AD poet Manilius, which reads in Latin: Transire suum pectus mundoque potiri ("Rise above oneself and grasp the world").[121][122][123]

Archimedes has appeared on postage stamps issued by East Germany (1973), Greece (1983), Italy (1983), Nicaragua (1971), San Marino (1982), and Spain (1963).[124]

The exclamation of Eureka! attributed to Archimedes is the state motto of California. In this instance, the word refers to the discovery of gold near Sutter's Mill in 1848 which sparked the California gold rush.[125]

See also

Concepts

- Arbelos

- Archimedean point

- Archimedes' axiom

- Archimedes number

- Archimedes paradox

- Archimedean solid

- Archimedes' twin circles

- Methods of computing square roots

- Salinon

- Steam cannon

People

References

Notes

- ^ Doric Greek: Ἀρχιμήδης, pronounced [arkʰimɛːdɛ̂ːs].

- ^ In the preface to On Spirals addressed to Dositheus of Pelusium, Archimedes says that "many years have elapsed since Conon's death." Conon of Samos lived c. 280–220 BC, suggesting that Archimedes may have been an older man when writing some of his works.

- ^ a b The treatises by Archimedes known to exist only through references in the works of other authors are: On Sphere-Making and a work on polyhedra mentioned by Pappus of Alexandria; Catoptrica, a work on optics mentioned by Theon of Alexandria; Principles, addressed to Zeuxippus and explaining the number system used in The Sand Reckoner; On Balances or On Levers; On Centers of Gravity; On the Calendar.

- ^ Boyer, Carl Benjamin. 1991. A History of Mathematics. ISBN 978-0-471-54397-8: "Arabic scholars inform us that the familiar area formula for a triangle in terms of its three sides, usually known as Heron's formula – , where is the semiperimeter – was known to Archimedes several centuries before Heron lived. Arabic scholars also attribute to Archimedes the 'theorem on the broken chord' ... Archimedes is reported by the Arabs to have given several proofs of the theorem."

Citations

- ^ Knorr, Wilbur R. (1978). "Archimedes and the spirals: The heuristic background". Historia Mathematica. 5 (1): 43–75. doi:10.1016/0315-0860(78)90134-9.

"To be sure, Pappus does twice mention the theorem on the tangent to the spiral [IV, 36, 54]. But in both instances the issue is Archimedes' inappropriate use of a 'solid neusis,' that is, of a construction involving the sections of solids, in the solution of a plane problem. Yet Pappus' own resolution of the difficulty [IV, 54] is by his own classification a 'solid' method, as it makes use of conic sections." (p. 48)

- ^ "Archimedes". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ "Archimedes (c. 287 – c. 212 BC)". BBC History. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ^

John M. Henshaw (2014). An Equation for Every Occasion: Fifty-Two Formulas and Why They Matter. JHU Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-4214-1492-8.

Archimedes is on most lists of the greatest mathematicians of all time and is considered the greatest mathematician of antiquity.

Calinger, Ronald (1999). A Contextual History of Mathematics. Prentice-Hall. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-02-318285-3.Shortly after Euclid, compiler of the definitive textbook, came Archimedes of Syracuse (ca. 287 212 BC), the most original and profound mathematician of antiquity.

"Archimedes of Syracuse". The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. January 1999. Retrieved 9 June 2008. Sadri Hassani (2013). Mathematical Methods: For Students of Physics and Related Fields. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-387-21562-4.Archimedes is arguably believed to be the greatest mathematician of antiquity.

Hans Niels Jahnke. A History of Analysis. American Mathematical Soc. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8218-9050-9.Archimedes was the greatest mathematician of antiquity and one of the greatest of all times

Stephen Hawking (2007). God Created The Integers: The Mathematical Breakthroughs that Changed History. Running Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7624-3272-1.Archimedes, the greatest mathematician of antiquity

Hirshfeld, Alan (2009). Eureka Man: The Life and Legacy of Archimedes. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 206.the Archimedes Palimpsest has ridden the roiling waves of circumstance to become the most celebrated link to antiquity's greatest mathematician-inventor

Vallianatos, Evaggelos (27 July 2014). "Archimedes: The Greatest Scientist Who Ever Lived". HuffPost. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

Kiersz., Andy (2 July 2014). "The 12 mathematicians who unlocked the modern world". Business Insider. Retrieved 3 May 2021. "Archimedes". Retrieved 3 May 2021. Livio, Mario (6 December 2017). "Who's the Greatest Mathematician of Them All?". HuffPost. Retrieved 7 May 2021. - ^ Kirfel, Christoph (2013). "A generalisation of Archimedes' method". The Mathematical Gazette. 97 (538): 43–52. doi:10.1017/S0025557200005416. ISSN 0025-5572. JSTOR 24496758.

- ^ a b c Powers, J. (2020). "Did Archimedes do calculus?" (PDF). maa.org. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ a b Jullien, V. (2015), J., Vincent (ed.), "Archimedes and Indivisibles", Seventeenth-Century Indivisibles Revisited, Science Networks. Historical Studies, vol. 49, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 451–457, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-00131-9_18, ISBN 978-3-319-00131-9

- ^ O'Connor, J.J.; Robertson, E.F. (February 1996). "A history of calculus". University of St Andrews. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- ^ a b c d Heath, Thomas L. 1897. Works of Archimedes.

- ^ Goe, G. (1972). "Archimedes' theory of the lever and Mach's critique". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A. 2 (4): 329–345. Bibcode:1972SHPSA...2..329G. doi:10.1016/0039-3681(72)90002-7.

- ^ Berggren, J. L. (1976). "Spurious Theorems in Archimedes' Equilibrium of Planes: Book I". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 16 (2): 87–103. doi:10.1007/BF00349632. JSTOR 41133463.

- ^ a b c Graf, Erlend H. (2004). "Just What Did Archimedes Say About Buoyancy?". The Physics Teacher. 42 (5): 296–299. Bibcode:2004PhTea..42..296G. doi:10.1119/1.1737965.

- ^ Høyrup, Jens (2017). "Archimedes: Knowledge and Lore from Latin Antiquity to the Outgoing European Renaissance" (PDF). Gaņita Bhāratī. 39 (1): 1–22. Reprinted in Hoyrup, J. (2019). Selected Essays on Pre- and Early Modern Mathematical Practice. pp. 459–477. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-19258-7_17.

- ^ Leahy, A. (2018). "The method of Archimedes in the seventeenth century". The American Monthly. 125 (3): 267–272. doi:10.1080/00029890.2018.1413857.

- ^ "Works, Archimedes". University of Oklahoma. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Paipetis, Stephanos A.; Ceccarelli, Marco, eds. (8–10 June 2010). The Genius of Archimedes – 23 Centuries of Influence on Mathematics, Science and Engineering: Proceedings of an International Conference held at Syracuse, Italy. History of Mechanism and Machine Science. Vol. 11. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-9091-1. ISBN 978-90-481-9091-1.

- ^ "Archimedes – The Palimpsest". Walters Art Museum. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- ^ Flood, Alison. "Archimedes Palimpsest reveals insights centuries ahead of its time". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ Plutarch (October 1996). Parallel Lives Complete e-text from Gutenberg.org – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ a b c d e f Dijksterhuis, Eduard J. [1938] 1987. Archimedes, translated. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08421-3.

- ^ a b Shapiro, A. E. (1975). "Archimedes's measurement of the Sun's apparent diameter". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 6 (2): 75–83. Bibcode:1975JHA.....6...75S. doi:10.1177/002182867500600201.

- ^ a b Acerbi, F. (2008). Archimedes. New Dictionary of Scientific Biography. pp. 85–91.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Rorres, Chris. "Death of Archimedes: Sources". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "Siege of Syracuse". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ "Tomb of Archimedes". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "Tomb of Archimedes: Sources". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "Tomb of Archimedes – Illustrations". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ a b "The Planetarium of Archimedes". studylib.net. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "The Death of Archimedes: Illustrations". math.nyu.edu. New York University. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ a b Plutarch. Extract from Parallel Lives. fulltextarchive.com. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- ^ Jaeger, Mary. Archimedes and the Roman Imagination. p. 113.

- ^ a b Rorres, Chris (ed.). "The Golden Crown: Sources". New York University. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- Morgan, Morris Hicky (1914). Vitruvius: The Ten Books on Architecture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 253–254.

Finally, filling the vessel again and dropping the crown itself into the same quantity of water, he found that more water ran over the crown than for the mass of gold of the same weight. Hence, reasoning from the fact that more water was lost in the case of the crown than in that of the mass, he detected the mixing of silver with the gold, and made the theft of the contractor perfectly clear.

- Vitruvius (1567). De Architetura libri decem. Venice: Daniele Barbaro. pp. 270–271.

Postea vero repleto vase in eadem aqua ipsa corona demissa, invenit plus aquae defluxisse in coronam, quàm in auream eodem pondere massam, et ita ex eo, quod plus defluxerat aquae in corona, quàm in massa, ratiocinatus, deprehendit argenti in auro mixtionem, et manifestum furtum redemptoris.

- Morgan, Morris Hicky (1914). Vitruvius: The Ten Books on Architecture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 253–254.

- ^ a b Vitruvius (31 December 2006). De Architectura, Book IX, Introduction, paragraphs 9–12 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ "Incompressibility of Water". Harvard University. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "The Golden Crown". Drexel University. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ^ Carroll, Bradley W. "Archimedes' Principle". Weber State University. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Van Helden, Al. "The Galileo Project: Hydrostatic Balance". Rice University. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "The Golden Crown: Galileo's Balance". Drexel University. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ^ Finlay, M. (2013). Constructing ancient mechanics Archived 14 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine [Master's thesis]. University of Glassgow.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "The Law of the Lever According to Archimedes". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- ^ Clagett, Marshall (2001). Greek Science in Antiquity. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-41973-2.

- ^ Dougherty, F.C.; Macari, J.; Okamoto, C. "Pulleys". Society of Women Engineers. Archived from the original on 18 July 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Quoted by Pappus of Alexandria in Synagoge, Book VIII

- ^ a b Berryman, S. (2020). "How Archimedes Proposed to Move the Earth". Isis. 111 (3): 562–567. doi:10.1086/710317.

- ^ Casson, Lionel (1971). Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-03536-9.

- ^ "Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists, BOOK V., chapter 40". perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ Dalley, Stephanie; Oleson, John Peter (2003). "Sennacherib, Archimedes, and the Water Screw: The Context of Invention in the Ancient World". Technology and Culture. 44 (1).

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "Archimedes's screw – Optimal Design". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ "SS Archimedes". wrecksite.eu. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "Archimedes's Claw – Illustrations and Animations – a range of possible designs for the claw". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Carroll, Bradley W. "Archimedes' Claw: watch an animation". Weber State University. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ^ "Ancient Greek Scientists: Hero of Alexandria". Technology Museum of Thessaloniki. Archived from the original on 5 September 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- ^ Archimedes's contemporary Diocles made no mention of Archimedes or burning ships in his treatise about focusing reflectors. Diocles, On Burning Mirors, ed. G. J. Toomer, Berlin: Springer, 1976. Lucian, Hippias, ¶ 2, in Lucian, vol. 1, ed. A. M. Harmon, Harvard, 1913, pp. 36–37, says Archimedes burned ships with his techne, "skill". Galen, On temperaments 3.2, mentions pyreia, "torches". Anthemius of Tralles, On miraculous engines 153 [Westerman]. Knorr, Wilbur (1983). "The Geometry of Burning-Mirrors in Antiquity". Isis. 74 (1): 53–73. doi:10.1086/353176. ISSN 0021-1753.

- ^ Simms, D. L. (1977). "Archimedes and the Burning Mirrors of Syracuse". Technology and Culture. 18 (1): 1–24. doi:10.2307/3103202. JSTOR 3103202.

- ^ "Archimedes Death Ray: Testing with MythBusters". MIT. Archived from the original on 20 November 2006. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ John Wesley. "A Compendium of Natural Philosophy (1810) Chapter XII, Burning Glasses". Online text at Wesley Center for Applied Theology. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- ^ "TV Review: MythBusters 8.27 – President's Challenge". 13 December 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "World's Largest Solar Furnace". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ Evans, James (1 August 1999). "The Material Culture of Greek Astronomy". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 30 (3): 238–307. Bibcode:1999JHA....30..237E. doi:10.1177/002182869903000305.

But even before Hipparchus, Archimedes had described a similar instrument in his Sand-Reckoner. A fuller description of the same sort of instrument is given by Pappus of Alexandria ... Figure 30 is based on Archimedes and Pappus. Rod R has a groove that runs its whole length ... A cylinder or prism C is fixed to a small block that slides freely in the groove (p. 281).

- ^ Toomer, G. J.; Jones, Alexander (7 March 2016). "Astronomical Instruments". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.886. ISBN 9780199381135.

Perhaps the earliest instrument, apart from sundials, of which we have a detailed description is the device constructed by Archimedes (Sand-Reckoner 11-15) for measuring the sun's apparent diameter; this was a rod along which different coloured pegs could be moved.

- ^ Cicero. "De re publica 1.xiv §21". thelatinlibrary.com. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Cicero (9 February 2005). De re publica Complete e-text in English from Gutenberg.org. Retrieved 18 September 2007 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Wright, Michael T. (2017). "Archimedes, Astronomy, and the Planetarium". In Rorres, Chris (ed.). Archimedes in the 21st Century: Proceedings of a World Conference at the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Trends in the History of Science. Cham: Springer. pp. 125–141. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-58059-3_7. ISBN 978-3-319-58059-3.

- ^ Noble Wilford, John (31 July 2008). "Discovering How Greeks Computed in 100 B.C." The New York Times. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ "The Antikythera Mechanism II". Stony Brook University. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ "Ancient Moon 'computer' revisited". BBC News. 29 November 2006. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "Spheres and Planetaria". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Russo, L. (2013). "Archimedes between legend and fact". Lettera Matematica. 1 (3): 91–95. doi:10.1007/s40329-013-0016-y.

It is amazing that for a long time Archimedes's attitude towards the applications of science was deduced from the acritical acceptance of the opinion of Plutarch: a polygraph who lived centuries later, in a cultural climate that was completely different, certainly could not have known the intimate thoughts of the scientist. On the other hand, the dedication with which Archimedes developed applications of all kinds is well documented: of catoptrica, as Apuleius tells in the passage already cited (Apologia, 16), of hydrostatics (from the design of clocks to naval engineering: we know from Athenaeus (Deipnosophistae, V, 206d) that the largest ship in Antiquity, the Syracusia, was constructed under his supervision), and of mechanics (from machines to hoist weights to those for raising water and devices of war).

- ^ Drachmann, A. G. (1968). "Archimedes and the Science of Physics". Centaurus. 12 (1): 1–11. Bibcode:1968Cent...12....1D. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0498.1968.tb00074.x.

- ^ Carrier, Richard (2008). Attitudes toward the natural philosopher in the early Roman empire (100 B.C. to 313 A.D.) (Thesis). Retrieved 6 April 2021. "Hence Plutarch's conclusion that Archimedes disdained all mechanics, shop work, or anything useful as low and vulgar, and only directed himself to geometric theory, is obviously untrue. Thus, as several scholars have now concluded, his account of Archimedes appears to be a complete fabrication, invented to promote the Platonic values it glorifies by attaching them to a much-revered hero." (p.444)

- ^ Heath, T.L. "Archimedes on measuring the circle". math.ubc.ca. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ Kaye, R.W. "Archimedean ordered fields". web.mat.bham.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 16 March 2009. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- ^ Quoted in Heath, T.L. Works of Archimedes, Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-42084-4.

- ^ "Of Calculations Past and Present: The Archimedean Algorithm". maa.org. Mathematical Association of America. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ McKeeman, Bill. "The Computation of Pi by Archimedes". Matlab Central. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ Carroll, Bradley W. "The Sand Reckoner". Weber State University. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Encyclopedia of ancient Greece By Wilson, Nigel Guy p. 77 Archived 8 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 978-0-7945-0225-6 (2006)

- ^ Clagett, Marshall (1982). "William of Moerbeke: Translator of Archimedes". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 126 (5): 356–36 6. JSTOR 986212.

- ^ Clagett, Marshall (1959). "The Impact of Archimedes on Medieval Science". Isis. 50 (4): 419–429. doi:10.1086/348797.

- ^ "Editions of Archimedes's Work". Brown University Library. 1999.

- ^ Knorr, W. R. (1978). "Archimedes and the Elements: Proposal for a Revised Chronological Ordering of the Archimedean Corpus". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 19 (3): 211–290. doi:10.1007/BF00357582. JSTOR 41133526.

- ^ Sato, T. (1986). "A Reconstruction of The Method Proposition 17, and the Development of Archimedes' Thought on Quadrature...Part One". Historia scientiarum: International journal of the History of Science Society of Japan.

- ^ "English translation of The Sand Reckoner". University of Waterloo. 2002. Archived from the original on 1 June 2002. Adapted from Newman, James R. (1956). The World of Mathematics. Vol. 1. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- ^ Heath, T.L. (1897). The Works of Archimedes. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Netz, Reviel (2017). "Archimedes' Liquid Bodies". In Buchheim, Thomas; Meißner, David; Wachsmann, Nora (eds.). ΣΩΜΑ: Körperkonzepte und körperliche Existenz in der antiken Philosophie und Literatur. Hamburg: Felix Meiner. pp. 287–322. ISBN 978-3-7873-2928-1.

- ^ Stein, Sherman (2004). "Archimedes and his floating paraboloids". In Hayes, David F.; Shubin, Tatiana (eds.). Mathematical Adventures for Students and Amateurs. Washington: Mathematical Association of America. pp. 219–231. ISBN 0-88385-548-8. Rorres, Chris (2004). "Completing Book II of Archimedes's on Floating Bodies". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 26 (3): 32–42. doi:10.1007/bf02986750. Girstmair, Kurt; Kirchner, Gerhard (2008). "Towards a completion of Archimedes' treatise on floating bodies". Expositiones Mathematicae. 26 (3): 219–236. doi:10.1016/j.exmath.2007.11.002.

- ^ a b "Graeco Roman Puzzles". Gianni A. Sarcone and Marie J. Waeber. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- ^ Kolata, Gina (14 December 2003). "In Archimedes' Puzzle, a New Eureka Moment". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Ed Pegg Jr. (17 November 2003). "The Loculus of Archimedes, Solved". Mathematical Association of America. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "Archimedes' Stomachion". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- ^ Krumbiegel, B. and Amthor, A. Das Problema Bovinum des Archimedes, Historisch-literarische Abteilung der Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik 25 (1880) pp. 121–136, 153–171.

- ^ Calkins, Keith G. "Archimedes' Problema Bovinum". Andrews University. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- ^ "Archimedes' Book of Lemmas". cut-the-knot. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- ^ O'Connor, J.J.; Robertson, E.F. (April 1999). "Heron of Alexandria". University of St Andrews. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ Dilke, Oswald A. W. 1990. [Untitled]. Gnomon 62(8):697–99. JSTOR 27690606.

- ^ Berthelot, Marcel. 1891. "Sur l histoire de la balance hydrostatique et de quelques autres appareils et procédés scientifiques." Annales de Chimie et de Physique 6(23):475–85.

- ^ a b Wilson, Nigel (2004). "The Archimedes Palimpsest: A Progress Report". The Journal of the Walters Art Museum. 62: 61–68. JSTOR 20168629.

- ^ Easton, R. L.; Noel, W. (2010). "Infinite Possibilities: Ten Years of Study of the Archimedes Palimpsest". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 154 (1): 50–76. JSTOR 20721527.

- ^ Miller, Mary K. (March 2007). "Reading Between the Lines". Smithsonian.

- ^ "Rare work by Archimedes sells for $2 million". CNN. 29 October 1998. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ Christie's (n.d). Auction results

- ^ "X-rays reveal Archimedes' secrets". BBC News. 2 August 2006. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Piñar, G.; Sterflinger, K.; Ettenauer, J.; Quandt, A.; Pinzari, F. (2015). "A Combined Approach to Assess the Microbial Contamination of the Archimedes Palimpsest". Microbial Ecology. 69 (1): 118–134. Bibcode:2015MicEc..69..118P. doi:10.1007/s00248-014-0481-7. PMC 4287661. PMID 25135817.

- ^ Acerbi, F. (2013). "Review: R. Netz, W. Noel, N. Tchernetska, N. Wilson (eds.), The Archimedes Palimpsest, 2001". Aestimatio. 10: 34–46.

- ^

Father of mathematics: Jane Muir, Of Men and Numbers: The Story of the Great Mathematicians, p 19.

Father of mathematical physics: James H. Williams Jr., Fundamentals of Applied Dynamics, p 30., Carl B. Boyer, Uta C. Merzbach, A History of Mathematics, p 111., Stuart Hollingdale, Makers of Mathematics, p 67., Igor Ushakov, In the Beginning, Was the Number (2), p 114.

- ^ E.T. Bell, Men of Mathematics, p 20.

- ^ Alfred North Whitehead. "The Influence of Western Medieval Culture Upon the Development of Modern Science". Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ George F. Simmons, Calculus Gems: Brief Lives and Memorable Mathematics, p 43.

- ^ Reviel Netz, William Noel, The Archimedes Codex: Revealing The Secrets of the World's Greatest Palimpsest

- ^ "The Steam-Engine". Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle. Vol. I, no. 11. Nelson: National Library of New Zealand. 21 May 1842. p. 43. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ^ The Steam Engine. The Penny Magazine. 1838. p. 104.

- ^ Robert Henry Thurston (1996). A History of the Growth of the Steam-Engine. Elibron. p. 12. ISBN 1-4021-6205-7.

- ^ Matthews, Michael. Time for Science Education: How Teaching the History and Philosophy of Pendulum Motion Can Contribute to Science Literacy. p. 96.

- ^ "Archimedes – Galileo Galilei and Archimedes". exhibits.museogalileo.it. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ Yoder, J. (1996). "Following in the footsteps of geometry: the mathematical world of Christiaan Huygens". De Zeventiende Eeuw. Jaargang 12.

- ^ Boyer, Carl B., and Uta C. Merzbach. 1968. A History of Mathematics. ch. 7.

- ^ Jay Goldman, The Queen of Mathematics: A Historically Motivated Guide to Number Theory, p 88.

- ^ E.T. Bell, Men of Mathematics, p 237

- ^ W. Bernard Carlson, Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, p 57

- ^ Friedlander, Jay; Williams, Dave. "Oblique view of Archimedes crater on the Moon". NASA. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ^ Riehm, C. (2002). "The early history of the Fields Medal" (PDF). Notices of the AMS. 49 (7): 778–782.

The Latin inscription from the Roman poet Manilius surrounding the image may be translated 'To pass beyond your understanding and make yourself master of the universe.' The phrase comes from Manilius's Astronomica 4.392 from the first century A.D. (p. 782).

- ^ "The Fields Medal". Fields Institute for Research in Mathematical Sciences. 5 February 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Fields Medal". International Mathematical Union. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "Stamps of Archimedes". Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Retrieved 25 August 2007.

- ^ "California Symbols". California State Capitol Museum. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

Further reading

- Boyer, Carl Benjamin. 1991. A History of Mathematics. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-54397-8.

- Clagett, Marshall. 1964–1984. Archimedes in the Middle Ages 1–5. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Clagett, Marshall. 1970. "Archimedes". In Charles Coulston Gillispie, ed. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 1 (Abailard–Berg). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 213–231.

- Dijksterhuis, Eduard J. 1956. Archimedes. Translated by C. Dikshoorn. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard. Chapters 1–5 were translated from Archimedes (in Dutch). Groningen: Noordhoff. 1938. Later chapters appeared in Euclides Vols. 15–17, 20. 1938–1944. Reprinted 1987 by Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08421-1

- Gow, Mary. 2005. Archimedes: Mathematical Genius of the Ancient World. Enslow Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7660-2502-8.

- Hasan, Heather. 2005. Archimedes: The Father of Mathematics. Rosen Central. ISBN 978-1-4042-0774-5.

- Heath, Thomas L. 1897. Works of Archimedes. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-42084-4. Complete works of Archimedes in English.

- Netz, Reviel. 2004–2017. The Works of Archimedes: Translation and Commentary. 1–2. Cambridge University Press. Vol. 1: "The Two Books on the Sphere and the Cylinder". ISBN 978-0-521-66160-7. Vol. 2: "On Spirals". ISBN 978-0-521-66145-4.

- Netz, Reviel, and William Noel. 2007. The Archimedes Codex. Orion Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-297-64547-4.

- Pickover, Clifford A. 2008. Archimedes to Hawking: Laws of Science and the Great Minds Behind Them. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533611-5.

- Simms, Dennis L. 1995. Archimedes the Engineer. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-7201-2284-8.

- Stein, Sherman. 1999. Archimedes: What Did He Do Besides Cry Eureka?. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-718-2.

External links

- Heiberg's Edition of Archimedes. Texts in Classical Greek, with some in English.

- Archimedes on In Our Time at the BBC

- Works by Archimedes at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Archimedes at the Internet Archive

- Archimedes at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- Archimedes at PhilPapers

- The Archimedes Palimpsest project at The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland

- "Archimedes and the Square Root of 3". MathPages.com.

- "Archimedes on Spheres and Cylinders". MathPages.com.

- Testing the Archimedes steam cannon Archived 29 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Archimedes

- 3rd-century BC Greek people

- 3rd-century BC writers

- People from Syracuse, Sicily

- Ancient Greek engineers

- Ancient Greek inventors

- Ancient Greek geometers

- Ancient Greek physicists

- Hellenistic-era philosophers

- Doric Greek writers

- Sicilian Greeks

- Mathematicians from Sicily

- Scientists from Sicily

- Ancient Greek murder victims

- Ancient Syracusans

- Fluid dynamicists

- Buoyancy

- 280s BC births

- 210s BC deaths

- 3rd-century BC mathematicians

- 3rd-century BC Syracusans