Zero Time

| Zero Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 15 June 1971 | |||

| Studio | Mediasound, New York City | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 33:52 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer | ||||

| Tonto's Expanding Head Band chronology | ||||

| ||||

Zero Time is the debut album by British-American electronic music duo Tonto's Expanding Head Band, released on 15 June 1971 by Embryo Records. The album is a showcase for TONTO (The Original New Timbral Orchestra), a multitimbral, polyphonic synthesiser built by the two members of the band, Malcolm Cecil and Robert Margouleff, as a developed version of the Moog III synth in 1969. The duo began producing their own music together on the synth with the intention to push the machine's abilities, and their own abilities as musicians, to the limit. Recording their compositions in New York, they approached TONTO with no pre-conceived notions and intended to make music intrinsic to the synthesiser.

The album is instrumental and experimental in style, possessing a full capacity for the Moog's timbre and range. A science fiction influence is also evident on the album. The original album cover depicts a psychedelic painting by Carol Hertzer depicting stars and swirling nebulae. The album was not a commercial success but received positive attention from music critics, who complimented the album's usage of the Moog's "outer limits". The album is today considered a groundbreaking and innovative album which expanded the boundaries of the synthesiser. It has also proven influential, particularly on Stevie Wonder, who hired the duo to work on four of his most popular albums. Zero Time has been remastered and re-released several times.

Background and recording

[edit]In 1969, engineers Robert Margouleff and Malcolm Cecil, with the wishes of synthesiser pioneer Robert Moog, developed extra modules for the centrepiece unit of the Moog III keyboard. The creation was named the Original New Timbral Orchestra or TONTO.[4] Among the first synthesisers to create polyphonic sound, TONTO was a room-sized instrument that, according to one critic, resembled the cockpit of a science fiction film rocket ship,[5] and remains the largest Moog synthesiser in existence, built into slightly curving wooding cases assembled beside and atop each other.[4] Cecil explained that, with TONTO, he wanted to create the world's first multitimbral polyphonic synthesiser, displaying a different type of polyphony to what has come to define modern synthesisers. He said that, to him, "multitimbral" meant each note has its own tone quality as if the notes "come from separate instruments."[6]

After TONTO's creation, Robert Moog began to develop the Minimoog, leaving Cecil and Margouleff to take TONTO into the studio to begin using it in their own music. In 1971, they set out to create music displaying the synth's versatility, with no intention of gaining financially from the material but instead to simply curate inimitable soundscapes.[4] The music on Zero Time originated when the duo gradually began creating compositions together and "one thing led to another."[7] The music on the album was recorded at Mediasound Studios in New York City.[8] Working as a team, each took turns on TONTO while the other assisted. One's efforts would make a sound while the other would capture it on tape before the patch disappeared. Sometimes the duo would play simultaneously instead, both adding harmonies, melodies and bass lines and engineering sounds together.[7] Margouleff said:

"The temporariness of it, the chaotic quality of it, the ability to create these most wonderful sounds that are there for a second and then go away, then you act on the thing in a very impulsive way, much as a jazz musician acts impulsively on his instrument. But the creation of the sound itself, the invention of the instrument itself comes very briefly to light out the chaos, and then it's gone again."[7]

In their book Analog Days, Trevor Pinch and Frank Trocco said the sounds Cecil and Margouleff produced were "neither kitschy, funny, nor imitative," and instead pushed the machine to its limits. Cecil reflected that, instead of approaching TONTO with pre-conceived notions, they attempted to make music "intrinsic to the instrument," with the synth dictating how the duo progressed. Although they were tempted to add to the sounds on their music, they ultimately remained purists and opposed the idea.[7] When Cecil played two of the completed tracks, "Cybernaut" and "Aurora", to his friend Herbie Mann, the latter offered them a record contract with his label Embryo Records. Titling the album Zero Time, they adopted the band name Tonto's Expanding Head Band,[7] a reflection of the psychedelic culture that Cecil and Margouleff felt part of.[9] As Cecil later explained, part of the idea for launching the Expanding Head Band was that the duo were going to begin creating a track which would then be added to by other synthesists individually, but this plan nonetheless fell through as the tape never left the duo's studio.[7]

Composition

[edit]Zero Time displays a wide feel for the range and timbres of the Moog and emphasises the 'fat sound' created by the low-pass filter of the instrument's bass range.[10] The synth waves on the album are pristine and crisp, curating a "new sound that feels digital" according to Jim Brenholts of AllMusic.[11] As TONTO is the only instrument on Zero Time, the album is entirely electronic.[1] Musically, the album is considered by writers to be experimental,[1] psychedelic,[2] progressive[2] and space music in style,[3] with writer Jim DeRogatis also referring to the album's style as "trippy instrumental Muzak."[12] Although the album is almost entirely instrumental, "Riversong" features vocals credited to TONTO which were processed through the machine until they resemble "deeply synthesised signals" more than vocals.[13] The influence of science fiction is also present on the album, as is evident by the titles of "Cybernaut", "Jetsex" and "Aurora".[14]

Side one of Zero Time is subtitled "Outside" and contains shorter, more rhythmic material than the second side;[13] Cecil, who is a bass player, felt the rhythmic emphasis was because rhythms are "part of my stock in trade."[15] The album's warm "fat bass" sounds are readily exemplified on the opening track "Cybernaut".[7] Side two of the album, subtitled "Inside", contains the longer, more complex tracks[13] and was described by Keyboard as stylistically different to other music of the period.[15]

"Aurora" grew out of the duo's experiments playing in monophonic styles, layering different elements and experimenting with space,[15] and originally ran for 27 minutes before it was completed and edited down.[9] The track contains washes of ambient music,[7] and features three glide tones which go up an octave; this is because, when discussing intervals during production, the duo questioned why there should only be twelve tones to the scale. Cecil explained: "With the synthesizer we're not limited to twelve tones. We can change the tuning and put 17, 19, 25 — pick a number! We wondered how many intervals there were in an octave and decided to check it out with these glide tones. They're spread over a long time because we were trying to pick out individual notes."[15] When the duo came across an intriguing interval, they would look at another and comment, "Hey, listen to that one!"[15]

"Riversong" features synthesised voices,[7] and a distinctive sound resembling a gong or bell.[16] Due to the duo's rejection of "imitative synthesis," it was rare that they used a sound on TONTO that resembled a conventional instrument, as they wanted to capture the instrument's own, distinctive sounds. They nonetheless obliged for the bell sound but, being synthesiser purists, they did not want to use any conventional instrumentation on the all-synthesiser album, and sought to recreate the sound on TONTO.[16] Although the duo had figured out which envelope to use in production, no sound initially resembled a bell. Cecil then took inspiration from Hermann von Helmholtz's work Sensations of Tone, in which Helmholtz analysed the bell of the Great Lavra Bell Tower, Kyiv, and its harmonies. Cecil and Margouleff dialled up the Kyiv bell's harmonies in the same way Helmholtz had described them, fed them into TONTO's mixer, filtered them and applied the envelope, thus creating the bell sound. Cecil recalled: "It was unbelievable! We were hugging each other, dancing round the studio. 'We did it, we did it!'."[16]

Release

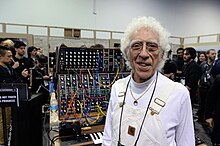

[edit]Zero Time was released in the United States by Embryo Records on 15 June 1971 and in the United Kingdom and Canada by both Embryo and its parent label Atlantic Records.[8] Haig Adishian is credited for designing the album artwork.[8] The cover features a painting by Carol Hertzer entitled Apollo on Mars,[8] which depicts a psychedelic montage showing stars, planets and swirling nebulae.[7] The inner sleeve also depicts a painting by Issac Abrams entitled Seed Dream,[8] while the back cover features a fish-eye lens photograph taken by Joel Brodsky depicting the duo grinning beside one of TONTO’s patch bays and "above forest of wires and knobs."[8][13] The album was not a commercial success,[17] despite Mike Reed of Atlantic's parent label Warner Bros. Records putting a "strong push" towards promoting and distributing the album in Toronto.[18]

Atlantic Records re-released the album in 1975 under the new name Tonto's Expanding Head Band,[19] by which point a second album by the duo entitled It's About Time, with the shortened band name Tonto, had been released in 1972.[4] The new version of Zero Time featured a new album cover featuring an illustration by Jeffrey Schier;[19] this cover has since become known as the "frogs and hands" sleeve.[13] The music from both Zero Time and It's About Time were remastered and released together on CD in 1996 by Viceroy Vintage as Tonto Rides Again.[20] Rhino Records released a remastered CD of Zero Time in Europe on 28 July 2008 as part of their "Classic Album Series,"[21] while Prog Temple issued further CD versions in Europe in 2012 and the US in 2013.[22] Real Gone Music released another remastered CD version of the album in 2013.[5]

Critical reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

Despite its lack of commercial success, Zero Time was critically acclaimed.[17] Timothy Crouse of Rolling Stone was very favourable, despite finding the possibilities in using a Moog exciting and somewhat unsettling: "After all, a Moog theoretically can produce any sound, and produce it instantly, so that a clarinet might scale three mellow ascending notes and then on the fourth note play the sound of the sea giving up her dead."[23] Cecil and Margouleff only became aware of the album's acclaim when, in their words, "somebody brings us [the latest issue of] Rolling Stone and, lo and behold, there's a full-page article on how wonderful we are."[7] In their review, Billboard wrote that the duo "effectively travel to the outer limits of the Moog, including a 'vocal' by the machine," and concluded that the album would appeal to "the progressive undergrounders."[24]

In Britain, Dick Meadows of Sounds felt that upon first sight, Zero Time would "put fear into the hearts of stronger men than me. After all, two whole sides of Moog music is a pretty big mountain to climb by any standard. I quite expected to be certified insane by the end of the day." However, he found listening to the album made his prejudices seem foolish, and hailed the album as "a work of considerable magnitude, forging a hefty wedge into the unknowns of electronic music which a lot of good musicians will swear is one of the main directions we are headed." His review concluded that "comparisons with tangible things seems about the best way to explain what is still largely an unknown new music force."[25]

In a retrospective review, Jim Brenholts of AllMusic called the record "one of the first—and perhaps best of—all electronic albums." He wrote that: "For historical purposes, this rare and collectible album is essential. For musical integrity, it still stands the test of time and is essential. It is a classic with no real peers, but it will appeal to fans of Mother Mallard's Portable Masterpiece Company, Jean Michel Jarre, Tangerine Dream, Wendy Carlos, and Fripp & Eno in terms of its uniqueness and legacy."[11] Musician Julian Cope, also a musicologist,[26] wrote that Zero Time possessed some of the "warmest and most sweetly soothing sounds to arise from American synthesizer operators in the early months of the seventies." He felt that the album utilised elements of the sounds that defined Paul Beaver's Moog experiments, and those on the soundtracks for The Trip (1967) and Performance (1970), while being lighter and more "stratospheric." He also felt it was inarguable that Zero Time boasted "the richest Moog synthesiser bass tones ever."[13]

Legacy

[edit]"Though it was snubbed by the public, Zero Time would heavily influence the electronic fascinations of the new decade's artists. Its lasting impact is almost silently infused in the cultural fabric, since the album remains, by and large, a collectible obscurity."

—Author Zeith Lundy[27]

Although Zero Time quickly faded into obscurity, it was embraced by audiophiles upon release due to the pristine sound highlighting the strength of their speaker systems.[15] The album soon became an "underground classic,"[7] and has since gone on to be considered by writers and journalists to be a groundbreaking and pioneering release.[7][28] Steven McDonald of AllMusic called the album "a revolutionary piece of work that set out to explore the capabilities of the synthesizer with no regard for conceptions of pop success," and wrote that it is "still considered to be a turning point in the use of synthesisers in modern music."[4] Despite finding Zero Time more notable for its place in the history of electronic music than for its content, Austin Trunick of Under the Radar nonetheless said it was "ahead of its time" and similar to other albums released much later than 1971.[5] Zero Time is also counted among the "classic Moog psychedelic records from the period" in the book Moments of Valuation: Exploring Sites of Dissonance,[10] while writer James McCarraher described it as a "synthesiser masterpiece."[29]

In the 2013 book Adventure Rocketship, the album features in the list "Possible Futures: 20 Mind-Expanding Ways to Start Your SF Album Collection", a list of records with science fiction themes and "devotions to visions of the future." The album was recommended for inclusion in the list by producer and musician Youth.[14] In 2015, Rolling Stone included the album in its list of "10 Weird Albums Rolling Stone Loved in the 1970s You've Never Heard," with the accompanying text saying: "At the dawn of the age of synthesizers, the instrument was so novel that people recorded whole LPs just to showcase its capabilities. While many of them were charmless, this album was beautiful and contemplative. [...] We thought that even if you owned other electronic records, you might find that this record divides your collection into two parts — Zero Time and everything else."[23] Cope wrote that despite being less strident than purely electronic krautrock, some of the passages on Zero Time anticipated the "quieter paces" on side two of Kraftwerk's Autobahn (1974).[13]

Influence

[edit]

Stevie Wonder had a chance encounter with Zero Time and became a big fan of the album, steering him in a new direction as he began using synthesisers in his music.[29] He was so impressed with Zero Time that, taking a copy of the album with him, he met with Tonto's Expanding Head Band and said "I don't believe this was all done on one instrument. Show me."[30] Despite Wonder's blindness, they taught him how to operate a Moog and get the best results from the instrument.[17][29] This was the start of a long-lasting collaboration between Wonder and Tonto's Expanding Head Band, who feature alongside the TONTO synth on a series of critically acclaimed Stevie Wonder albums that saw his artistic growth: Music of My Mind (1972), Talking Book (1972), Innervisions (1973) and Fulfillingness' First Finale (1974).[13] The collaboration was described by John Dilberto of Keyboard as "[changing] the perspectives of black pop music as much as the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper altered the concept of white rock."[31] On the albums, Cecil and Margouleff are credited for playing the instrument, as well as programming, production, associate production and engineering, and these Wonder collaborations helped the duo achieve much more authoritative status than their own projects, including Zero Time, ever had.[32] According to writer Ron Boy, "Wonder's huge impact in this era ensured their share of reflective glory."[32] Reflecting on Zero Time, Stevie Wonder said:

"How great it is at a time when technology and the science of music is at its highest point of evolution, to have the reintroduction of two of the most prominent forefathers in this music be heard again. It can be said of this work that it parallels with good wine. As it ages it only gets better with time. A toast to greatness... a toast to Zero Time... forever."[14]

Keyboard magazine credit the album, via its influence on Wonder's albums, as "quietly influencing the shape of progressive funk and R&B."[15] Guitarist Steve Hillage also hired Malcolm Cecil to co-produce and play TONTO on Motivation Radio (1977), the album that moved Hillage into dance music.[33] The album also influenced Devo, and Mark Mothersbaugh of the band said that, in the "cultural wasteland of the Midwest," the 1975 re-release of Zero Time was "an inspirational indicator for starving Spudboys who had grown tired of the soup de jour. It was official – noise was now Muzak, and Muzak was now noise."[20] Mothersbaugh later purchased TONTO in 1996.[4] The influence of Zero Time was the subject of an essay by Richie Unterberger included in the liner notes of the album's 2013 Real Gone Music reissue.[5]

Track listing

[edit]Side one

[edit]- "Cybernaut" – 4:30

- "Jetsex" – 4:14

- "Timewhys" – 4:57

Side two

[edit]- "Aurora" – 6:48

- "Riversong" (lyrics by Tama Starr) – 8:00

- "Tama" – 5:23

Personnel

[edit]- Haig Adishian – album design

- Herbie Mann – executive producer

- Sol Kessler – mastering consultant

- Carol Herzer – cover painting ("Through the Wave, 1969")

- Isaac Abrams – inside painting ("Seed Dream")

- Joel Brodsky – photography

- Malcolm Cecil – writing, programming, performing, engineering, producing

- Robert Margouleff – writing, programming, performing, engineering, producing

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Gulla, Bob (2008). Icons of R&B and Soul: An Encyclopedia of the Artists Who Revolutionized Rhythm, Volume 2. Westport: Greenwood. pp. 316–317. ISBN 978-0313340468. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d Collins, Nick; d'Escrivan, Julio (9 November 2017). The Cambridge Companion to Electronic Music (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107590021. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ a b Listed in "A Classic Space Music Countdown to Liftoff: 10 Essential classic space music albums, counting down from 10 to 1" Time Warped in Space by Echoes Radio producer and host, John Diliberto Archived 2007-04-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c d e f McDonald, Steve. "Artist Biography by Steven McDonald". AllMusic. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d Trunick, Austin (9 October 2013). "Reissued and Revisited: Tonto's Expanding Head Band's Zero Time". Under the Radar. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ [1] Archived October 11, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Pinch, Trevor; Trocco, Frank (30 October 2014). Analog Days: The Invention and Impact of the Moog Synthesizer (New ed.). Harvard: Harvard University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0674016170.

- ^ a b c d e f Zero Time (liner). Tonto's Expanding Head Band. Embryo Records. 1971.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b "Forty Years Since TONTO, the first Modern Electronic Group". Echoes. 25 July 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ a b Berthoin Antal, Ariane; Hutter, Michael; Stark, David (29 January 2015). Moments of Valuation: Exploring Sites of Dissonance. Oxford: OUP. p. 25. ISBN 978-0198702504. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Brenholts, Jim. "AllMusic Review by Jim Brenholts". AllMusic. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ DeRogatis, Jim (1 December 2003). Turn on Your Mind: Four Decades of Great Psychedelic Rock. Wisconsin: Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 0634055488. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cope, Julian ("the Seth Man") (April 2001). "Unsung: TONTO'S EXPANDING HEAD BAND; ZERO TIME". Head Heritage. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Tidhar, Lavie; Maughan, Tim; Williams, Liz; Millar, Mark (20 May 2013). Adventure Rocketship!. ISBN 978-1906477738.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Tonto feature". Keyboard. 10: 44. 1984.

- ^ a b c Selinger, Evan (6 July 2006). Postphenomenology: A Critical Companion to Ihde. New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0791467880. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Betts, Graham (2 June 2014). Motown Encyclopedia. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1500471699. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Yorke, Ritchie (31 July 1971). "International News Report". Billboard. Vol. 83, no. 31. p. 45. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ a b Tonto's Expanding Head Band (liner). Tonto's Expanding Head Band. Atlantic Records. 1975.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b Tonto Rides Again (liner). Tonto's Expanding Head Band. Viceroy Vintage. 1996.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Zero Time (liner). Tonto's Expanding Head Band. Rhino Records. 2008.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Zero Time (liner). Tonto's Expanding Head Band. Prog Temple. 2012.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b Edwards, Gavin (23 June 2015). "10 Weird Albums Rolling Stone Loved in the 1970s You've Never Heard". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ "Special Merit Picks". Billboard. Vol. 83, no. 19. 8 July 1971. p. 42. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ "Tonto's Expanding Head Band: Zero Time (Embryo)". Rock's Back Pages. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Dwyer, Roisin (28 October 2014). "The Author Explodes – Julian Cope Interview". Hot Press. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ Lundy, Zeth (2011). Songs in the Key of Life (33 1/3). London, New York City: Continuum. p. ii. ISBN 978-0826419262. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ Lynskey, Dorian (1 November 2012). 33 Revolutions Per Minute. United Kingdom: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0571241354.

- ^ a b c McCarraher, James (5 February 2012). 101 Songs To Discover From The Seventies. Lulu.com. p. 111. ISBN 978-1447862666. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Irvin, Jim (1 November 2007). The Mojo Collection: 4th Edition: The Ultimate Music Companion. Edinburgh: Canongate Books. p. 315. ISBN 978-1841959733. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Robins, Wayne (11 October 2007). A Brief History of Rock, Off the Record. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415974738. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ a b Moy, Ron (29 May 2015). Authorship Roles in Popular Music: Issues and Debates. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1138780682. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Motivation Radio (remastered version) (liner). Steve Hillage. Virgin Records. 2007.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link)