Generation Z

| Part of a series on |

| Social generations of the Western world |

|---|

|

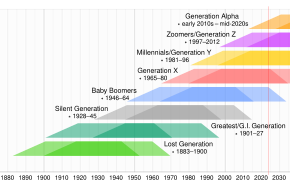

Generation Z (often shortened to Gen Z), also known as Zoomers,[1][2][3] is the demographic cohort succeeding Millennials and preceding Generation Alpha. Researchers and popular media use the mid-to-late 1990s as starting birth years and the early 2010s as ending birth years, with the generation most frequently being defined as people born from 1997 to 2012. Most members of Generation Z are the children of younger baby boomers or Generation X.[4][5]

As the first social generation to have grown up with access to the Internet and portable digital technology from a young age, members of Generation Z have been dubbed "digital natives"[6] even if they are not necessarily digitally literate[7] and may struggle in a digital work place.[8][9] Moreover, the negative effects of screen time are most pronounced in adolescents, as compared to younger children.[10] Compared to previous generations, members of Generation Z tend to live more slowly than their predecessors when they were their age,[11][12] have lower rates of teenage pregnancies, and consume alcohol (but not necessarily other psychoactive drugs) less often.[13][14][15] Generation Z teenagers are more concerned than older generations with academic performance and job prospects,[16][11] and are better at delaying gratification than their counterparts from the 1960s, despite concerns to the contrary.[17] Sexting among adolescents has grown in prevalence; the consequences of this remain poorly understood.[18] Youth subcultures have not disappeared, but they have been quieter.[19][20] Nostalgia is a major theme of youth culture in the 2010s and 2020s.[21][22][23]

Globally, there is evidence that girls in Generation Z are experiencing puberty at considerably younger ages compared to previous generations, with implications for their welfare and their future.[24][25][26][27][28] Furthermore, the prevalence of allergies among adolescents and young adults in this cohort is greater than the general population;[29][30] there is greater awareness and diagnosis of mental health conditions,[16][15][31][32] and sleep deprivation is more frequently reported.[33][34][35]

In many countries, Generation Z youth are more likely to be diagnosed with intellectual disabilities and psychiatric disorders than older generations.[36][37]

Around the world, members of Generation Z are spending more time on electronic devices and less time reading books than before,[38][39][40] with implications for their attention spans,[41][42] vocabulary,[43][44] academic performance,[45] and future economic contributions.[38] In Asia, educators in the 2000s and 2010s typically sought out and nourished top students; in Western Europe and the United States, the emphasis was on poor performers.[46] East Asian and Singaporean students consistently earned the top spots in international standardized tests in the 2010s.[47][48][49][50]

Etymology and nomenclature

The name Generation Z is a reference to the fact that it is the second generation after Generation X, continuing the alphabetical sequence from Generation Y (Millennials).[51][52]

Other proposed names for the generation included iGeneration,[53] Homeland Generation,[54] Net Gen,[53] Digital Natives,[53] Neo-Digital Natives,[55] Pluralist Generation,[53] Internet Generation,[56] and Centennials.[57]

"While there is no scientific process for deciding when a name has stuck, the momentum is clearly behind Gen Z."

Michael Dimmock, Pew Research Center[58]

The rapper MC Lars used the term iGeneration as early as 2005, as a song title.[59] Psychology professor and author Jean Twenge also used the term, intending it as the title of her 2006 book about Millennials but changing the title to Generation Me at the insistence of her publisher. Twenge later used the term for her 2017 book iGen. Others also claim to have coined the name.[53]

Author Neil Howe coined the term Homeland Generation in 2014, as a continuation of the Strauss–Howe generational theory with William Strauss. The term Homeland refers to being the first generation to enter childhood after protective surveillance state measures, like the Department of Homeland Security, were put into effect following the September 11 attacks.[54]

The Pew Research Center surveyed the various names for this cohort on Google Trends in 2019 and found that in the U.S., the term Generation Z was overwhelmingly the most popular, from then on calling it Gen Z in their research.[60] The Merriam-Webster and Oxford dictionaries both have official entries for Generation Z.[58]

In Japan, the cohort is described as neo-digital natives, a step beyond the previous cohort described as digital natives. Digital natives primarily communicate by text or voice, while neo-digital natives use video, video-telephony, and movies. This emphasizes the shift from PC to mobile and text to video among the neo-digital population.[55]

Zoomer is an informal term used to refer to members of Generation Z.[2] It combines the shorthand boomer, referring to baby boomers, with the "Z" from Generation Z. Zoomer in its current incarnation skyrocketed in popularity in 2018, when it was used in a 4chan internet meme mocking Gen Z adolescents via a Wojak caricature dubbed a "Zoomer".[61][62] Merriam-Webster's records suggest the use of the term zoomer in the sense of Generation Z dates back at least as far as 2016. It was added to the Merriam-Webster dictionary in October 2021[1] and to Dictionary.com in January 2020.[63] Prior to this, zoomer was occasionally used to describe particularly active baby boomers.[1]

Date and age range

Researchers and popular media have used the mid-to-late 1990s as starting birth years and the early 2010s as ending birth years to define Generation Z.

The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines Generation Z as "the generation of people born in the late 1990s and early 2000s."[64] The Collins Dictionary define Generation Z as "members of the generation of people born between the mid-1990s and mid-2010s.[65] The Oxford Dictionaries define Generation Z as "the group of people who were born between the late 1990s and the early 2010s, who are regarded as being very familiar with the internet."[66] Encyclopedia Britannica defines Generation Z as "the term used to describe Americans born during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Some sources give the specific year range of 1997–2012, although the years spanned are sometimes contested or debated because generations and their zeitgeists are difficult to delineate."[67]

The Pew Research Center has defined 1997 as the starting birth year for Generation Z, basing this on "different formative experiences", such as new technological and socioeconomic developments, as well as growing up in a world after the September 11 attacks.[68] Pew has not specified an endpoint for Generation Z, but used 2012 as a tentative endpoint for their 2019 report.[68] Numerous news outlets use a starting birth year of 1997, often citing Pew Research Center.[a] Various think tanks and analytics companies also have set a 1997 start date,[b] as do various management and consulting firms.[c] In a 2022 report, the U.S. Census designates Generation Z as "the youngest generation with adult members (born 1997 to 2013)."[86] Statistics Canada used 1997 to 2012, citing Pew Research Center, in a 2022 publication analyzing their 2021 census.[87] The Library of Congress uses 1997 to 2012, citing Pew Research as well.[88]

In her book iGen (2017), psychologist Jean Twenge defines the "iGeneration" as the cohort born between 1995 and 2012.[89] Other news outlets occasionally use 1995 as the starting birth year of Generation Z,[d] as do various management and consulting firms.[e]

The Australian Bureau of Statistics have used 1996 to 2010 to define Generation Z in a 2021 Census report.[97] Similarly, various management and consulting firms have used 1996 as a starting date for Generation Z.[f]

Individuals born in the Millennial and Generation Z cusp years have been sometimes identified as a "microgeneration" with characteristics of both generations. The most common name given for these cuspers is Zillennials.[101][102] Individuals born on the cusp of Generation Z and Generation Alpha have been referred to as Zalphas.[103]

Arts and culture

Happiness and personal values

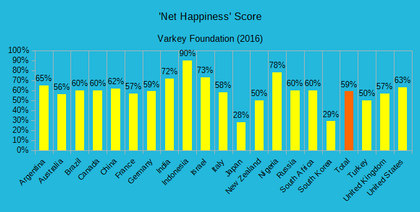

The Economist has described Generation Z as a more educated, well-behaved, stressed and depressed generation in comparison to previous generations.[16] In 2016, the Varkey Foundation and Populus conducted an international study examining the attitudes of over 20,000 people aged 15 to 21 in twenty countries: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Nigeria, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. They found that Gen Z youth were happy overall with the states of affairs in their personal lives (59%). The most unhappy young people were from South Korea (29%) and Japan (28%) while the happiest hailed from Indonesia (90%) and Nigeria (78%). In order to determine the overall 'happiness score' for each country, researchers subtracted the percentage of people who said they were unhappy from that of those who said they were happy. The most important sources of happiness were being physically and mentally healthy (94%), having a good relationship with one's family (92%), and one's friends (91%). In general, respondents who were younger and male tended to be happier. Religious faith came in last at 44%. Nevertheless, religion was a major source of happiness for Gen Z youth from Indonesia (93%), Nigeria (86%), Turkey (71%), China, and Brazil (both 70%). The top reasons for anxiety and stress were money (51%) and school (46%); social media and having access to basic resources (such as food and water) finished the list, both at 10%. Concerns over food and water were most serious in China (19%), India (16%), and Indonesia (16%); young Indians were also more likely than average to report stress due to social media (19%).[104]

According to the aforementioned study by the Varkey Foundation, the most important personal values to these people were helping their families and themselves get ahead in life (both 27%), followed by honesty (26%). Looking beyond their local communities came last at 6%. Familial values were especially strong in South America (34%) while individualism and the entrepreneurial spirit proved popular in Africa (37%). People who influenced youths the most were parents (89%), friends (79%), and teachers (70%). Celebrities (30%) and politicians (17%) came last. In general, young men were more likely to be influenced by athletes and politicians than young women, who preferred books and fictional characters. Celebrity culture was especially influential in China (60%) and Nigeria (71%) and particularly irrelevant in Argentina and Turkey (both 19%). For young people, the most important factors for their current or future careers were the possibility of honing their skills (24%), and income (23%) while the most unimportant factors were fame (3%) and whether or not the organization they worked for made a positive impact on the world (13%). The most important factors for young people when thinking about their futures were their families (47%) and their health (21%); the welfare of the world at large (4%) and their local communities (1%) bottomed the list.[104]

Common culture

During the 2000s and especially the 2010s, youth subcultures that were as influential as what existed during the late 20th century became scarcer and quieter, at least in real life though not necessarily on the Internet, and more ridden with irony and self-consciousness due to the awareness of incessant peer surveillance.[19][20] In Germany, for instance, youth appears more interested in a more mainstream lifestyle with goals such as finishing school, owning a home in the suburbs, maintaining friendships and family relationships, and stable employment, rather than popular culture, glamor, or consumerism.[105]

The COVID-19 pandemic struck when the oldest members of Generation Z were just joining the workforce and the rest were still in school.[106] While Generation Z proved to be less resilient than older cohorts, their fundamental values did not change, and they remained open to change, such as the transition towards hybrid school and remote work.[107]

Boundaries between the different youth subcultures appear to have been blurred, and nostalgic sentiments have risen.[19][20] Although nostalgia is normally associated with the elderly, this sentiment is now commonplace among those who came of age during the 2010s and 2020s. Struggling with present realities, Millennials and Generation Z long for the past, when life seemed simpler and less stressful, even if they have themselves never experienced it.[23] For example, although an aesthetic dubbed 'cottagecore' in 2018 has been around for many years,[108] it has become a subculture of Generation Z,[21] especially on various social media networks in the wake of the mass lockdowns imposed to combat the spread of COVID-19.[109] It is a form of escapism[108] and aspirational nostalgia.[22] Cottagecore became even more popular thanks to the commercial success of the 2020 album Folklore by musician Taylor Swift.[110][111][112] Nostalgic sentiments surged during and after the COVID pandemic. Among Generation Z, people are most nostalgic for the Y2K era (late 1990s and early 2000s).[113]

Nostalgia culture among Generation Z even extends to the usage of automobiles; in some countries, such as Indonesia, there are social media communities surrounding the purchasing used cars from earlier decades.[114]

A survey conducted by OnePoll in 2018 found that while museums and heritage sites remained popular among Britons between the ages of 18 and 30, 19% did not visit one in the previous year. There was a big gender gap in attitudes, with 16% of female respondents and 26% of male respondents saying they never visited museums. Generation Z preferred staying home and watching television or browsing social media networks to visiting museums or galleries. The researchers also found that cheaper tickets, more interactive exhibitions, a greater variety of events, more food and beverage options, more convenient opening hours, and greater online presence could attract the attention of more young people.[115] On the other hand, vintage fashion is growing in popularity among Millennial and Generation Z consumers.[116]

A 2019 report by Childwise found that children between the ages of five and sixteen in the UK spent an average of three hours each day online. Around 70% watched Netflix in the past week and only 10% watched their favorite programs on television. Among those who watched on-demand shows, 58% did so on a mobile phone, 51% on a television set, 40% via a tablet, 35% on a gaming console, and 27% on a laptop. About one out of four came from families with voice-command computer assistants such as Alexa. YouTube and Snapchat are the most popular gateways for music and video discovery. Childwise also found that certain television series aired between the 1990s and early 2000s, such as Friends, proved popular among young people of the 2010s.[117]

Figures from Nielsen and Magna Global revealed that the viewership of children's cable television channels such as Disney Channel, Cartoon Network, and Nickelodeon continued their steady decline from the early 2010s, with little to no alleviating effects due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced many parents and their children to stay at home.[118][119] Disney Channel in particular lost a third of their viewers in 2020, leading to closures in Scandinavia, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Southeast Asia.[119] On the other hand, streaming services saw healthy growth.[118][119]

During the first two decades of the 21st century, writing and reading fan fiction and creating fandoms of fictional works became a prevalent activity worldwide. Demographic data from various depositories revealed that those who read and wrote fan fiction were overwhelmingly young, in their teens and twenties, and female.[120][121][122] For example, an analysis published in 2019 by data scientists Cecilia Aragon and Katie Davis of the site FanFiction.Net showed that some 60 billion words of contents were added during the previous 20 years by 10 million English-speaking people whose median age was 151⁄2 years.[122] Fan fiction writers base their work on various internationally popular cultural phenomena such as K-pop, Star Trek, Harry Potter, Twilight, Doctor Who, and My Little Pony, known as 'canon', as well as other things they considered important to their lives, like natural disasters.[120][121][122] Much of fan fiction concerns the romantic pairing of fictional characters of interest, or 'shipping'.[123] Aragon and Davis argued that writing fan fiction stories could help young people combat social isolation and hone their writing skills outside of school in an environment of like-minded people where they can receive (anonymous) constructive feedback, what they call 'distributed mentoring'.[122] Informatics specialist Rebecca Black added that fan fiction writing could also be a useful resource for English-language learners. Indeed, the analysis of Aragon and Davis showed that for every 650 reviews a fan fiction writer receives, their vocabulary improved by one year of age, though this may not generalize to older cohorts.[124] On the other hand, children browsing fan fiction contents might be exposed to cyberbullying, crude comments, and other inappropriate materials.[123]

Generation Z has a plethora of options when it comes to music consumption, allowing for a highly personalized experience.[125] According to digital media company Sweety High's 2018 Gen Z Music Consumption & Spending Report, Spotify ranked first for music listening among Gen Z females, terrestrial radio ranked second, while YouTube was reported to be the preferred platform for music discovery.[126] In mid-2023, Spotify reported growth above expectation in the number of subscribers among Generation Z.[127] Additional research showed that within the past few decades, popular music has gotten slower; that majorities of listeners young and old preferred older songs rather than keeping up with new ones; that the language of popular songs was becoming more negative psychologically; and that lyrics were becoming simpler and more repetitive, approaching one-word sheets, something measurable by observing how efficiently lossless compression algorithms (such as the LZ algorithm) handled them.[128] On the other hand, texture and rhythm are becoming more complex.[129] Streaming services have made it extremely easy for listeners to sample songs, creating pressure on musicians to compose songs that are as easy to process and have as many hooks as possible.[129] Sad music is quite popular among adolescents, though it can dampen their moods, especially among girls.[125]

A 2020 survey conducted by the Center for Generational Kinetics, on 1000 members of Generation Z and 1000 Millennials, suggests that Generation Z still would like to travel, despite the COVID-19 pandemic and the recession it induced. However, Generation Z is more likely to look carefully for package deals that would bring them the most value for their money, as many of them are already saving money for buying a house and for retirement, and they prefer more physically active trips. Mobile-friendly websites and social-media engagements are both important.[130] They take advantage of the Internet to market and sell their fresh produce. In the United Kingdom, teenagers now prefer to get their news from social-media networks such as Instagram and TikTok and the video-sharing site YouTube rather than more traditional media, such as radio or television.[131]

In South Korea, people below the age of 40 are increasingly interested in relocating from the cities, especially Seoul, to the countryside and working on the farm. Working in a conglomerate like Samsung or Hyundai no longer appeals to young people, many of whom prefer to avoid becoming a workaholic or are pessimistic about their ability to be as successful as their fathers.[132]

Reading habits

In New Zealand, child development psychologist Tom Nicholson noted a marked decline in vocabulary usage and reading among schoolchildren, many of whom are reluctant to use the dictionary. According to a 2008 survey[needs update] by the National Education Monitoring Project, about one in five four-year and eight-year pupils read books as a hobby, a ten-percent drop from 2000.[43]

In the United Kingdom, a survey of 2,000 parents and children from 2013 by Nielsen Book found that 36% of children read books for pleasure on a daily basis, 60% on a weekly basis, and 72% were read to by their parents at least once per week. Among British children, the most popular leisure activities were watching television (36%), reading (32%), social networking (20%), watching YouTube videos (17%), and playing games on mobile phones (16%). Between 2012 and 2013, children reported spending more time with video games, YouTube, and texting but less time reading (down eight percent). Among children between the ages of 11 and 17, the share of non-readers grew from 13% to 27% between 2012 and 2013, those who read once to thrice a month (occasional readers) dropped from 45% to 38%, those who read for no more than an average of 15 minutes per week (light readers) rose from 23% to 27%, those who read between 15 and 45 minutes per week (medium readers) declined from 23% to 17%, and those who read at least 45 minutes a week (heavy readers) grew slightly from 15% to 16%.[133]

A survey by the National Literacy Trust from 2019 showed that only 26% of people below the age of 18 spent at least some time each day reading, the lowest level since records began in 2005. Interest in reading for pleasure declined with age, with five- to eight-year-olds being twice as likely to say they enjoyed reading compared to fourteen- to sixteen-year-olds. There was a significant gender gap in voluntary reading, with only 47% of boys compared to 60% of girls said they read for pleasure. One in three children reported having trouble finding something interesting to read.[39]

The aforementioned Nielsen Book survey found that the share of British households with at least one electronic tablet rose from 24% to 50% between 2012 and 2013.[133] According to a 2020 Childwise report based on interviews with 2,200 British children between the ages of five and sixteen, young people today are highly dependent on their mobile phones. Most now get their first device at the age of seven. By the age of eleven, having a cell phone became almost universal. Among those aged seven to sixteen, the average time spent on the phone each day is three and a third hours. 57% said they went to bed with their phones beside them and 44% told the interviewers they felt "uncomfortable" in the absence of their phones. Due to the nature of this technology—cell phones are personal and private devices—it can be difficult for parents to monitor their children's activities and shield them from inappropriate content.[134]

According to the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), fourth graders in 2016 were markedly less enthusiastic about reading than their predecessors in 2001 in 13 out of 20 countries and territories surveyed while their parents were even less keen on reading than they were.[135]

Demographics

-

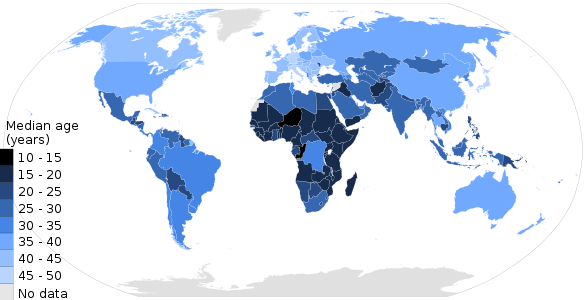

Median age by country in years in 2017. The youth bulge is evident in parts of Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

-

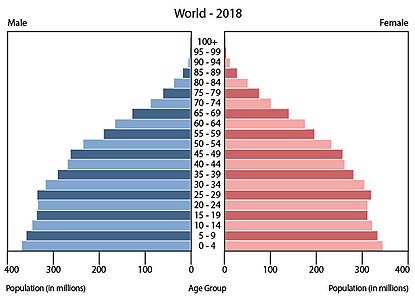

Population pyramid of the world in 2018

Although many countries have aging populations and declining birth rates, Generation Z is currently the largest generation on Earth.[136] Bloomberg's analysis of United Nations data predicted that, in 2019, members of Generation Z accounted for 2.47 billion (32%) of the 7.7 billion inhabitants of Earth, surpassing the Millennial population of 2.43 billion. The generational cutoff of Generation Z and Millennials for this analysis was placed at 2000 to 2001.[137][138]

Africa

Generation Z currently comprises the majority of the population of Africa.[139] In 2017, 60% of the 1.2 billion people living in Africa fell below the age of 25.[140]

In 2019, 46% of the South African population, or 27.5 million people, are members of Generation Z.[141]

Statistical projections from the United Nations in 2019 suggest that, in 2020, the people of Niger had a median age of 15.2, Mali 16.3, Chad 16.6, Somalia, Uganda, and Angola all 16.7, the Democratic Republic of the Congo 17.0, Burundi 17.3, Mozambique and Zambia both 17.6. This means that more than half of their populations were born in the first two decades of the 21st century. These are the world's youngest countries by median age.[142]

Asia

According to a 2022 McKinsey & Company insight, Generation Z will account for a quarter of the population of the Asia-Pacific region by 2025, and possess a global spending power of approximately US$140bn by 2030.[143]

As a result of cultural ideals, government policy, and modern medicine, there have been severe gender population imbalances in China and India. According to the United Nations, in 2018, there were 112 Chinese males for every hundred females ages 15 to 29; in India, there were 111 males for every hundred females in that age group. China had a total of 34 million excess males and India 37 million, more than the entire population of Malaysia. Together, China and India had a combined 50 million excess males under the age of 20. Such a discrepancy fuels loneliness epidemics, human trafficking (from elsewhere in Asia, such as Cambodia and Vietnam), and prostitution, among other societal problems.[144]

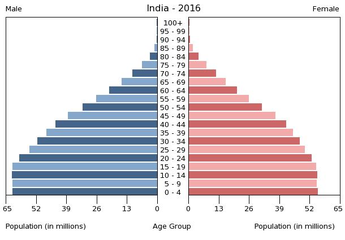

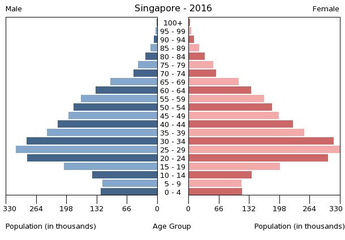

- Population pyramids of China, India, Japan, and Singapore in 2016

Europe

Out of the approximately 66.8 million people of the UK in 2019, there were approximately 12.6 million people (18.8%) in Generation Z, if defined as those born from 1997 to 2012.[145]

Generation Z is the most diverse generation in the European Union in regards to national origin.[146] In Europe generally, 13.9% of those ages 14 and younger in 2019 (which includes older Generation Alpha) were born in another EU Member State, and 6.6% were born outside the EU. In Luxembourg, 20.5% were born in another country, largely within the EU (6.6% outside the EU compared to 13.9% in another member state); in Ireland, 12.0% were born in another country; in Sweden, 9.4% were born in another country, largely outside the EU (7.8% outside the EU compared to 1.6% in another member state). In Finland, 4.5% of people aged 14 and younger were born abroad and 10.6% had a foreign-background in 2021.[147] However, Gen Z from eastern Europe is much more homogenous: in Croatia, only 0.7% of those aged 14 and younger were foreign-born; in the Czech Republic, 1.1% aged 14 and younger were foreign-born.[146]

Higher portions of those ages 15 to 29 in 2019 (which includes younger Millennials) were foreign born in Europe. Luxembourg had the highest share of young people (41.9%) born in a foreign country. More than 20% of this age group were foreign-born in Cyprus, Malta, Austria and Sweden. The highest shares of non-EU born young adults were found in Sweden, Spain and Luxemburg. Like with those under age 14, countries in eastern Europe generally have much smaller populations of foreign-born young adults. Poland, Lithuania, Slovakia, Bulgaria and Latvia had the lowest shares of foreign-born young people, at 1.4 to 2.5% of the total age group.[146]

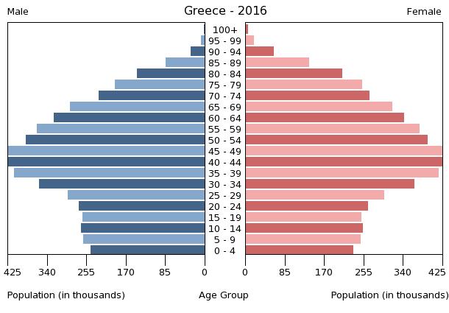

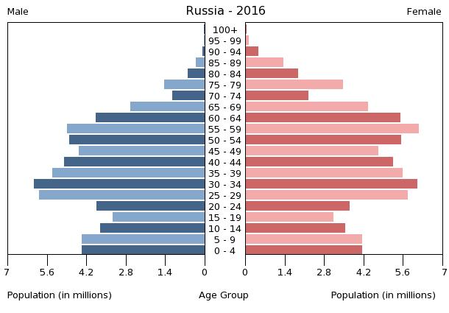

- Population pyramids of France, Greece, and Russia in 2016

North America

Data from Statistics Canada published in 2017 showed that Generation Z comprised 17.6% of the Canadian population.[148]

A report by demographer William Frey of the Brookings Institution stated that in the United States, the Millennials are a bridge between the largely white pre-Millennials (Generation X and their predecessors) and the more diverse post-Millennials (Generation Z and their successors).[149] Frey's analysis of U.S. Census data suggests that as of 2019, 50.9% of Generation Z is white, 13.8% is black, 25.0% Hispanic, and 5.3% Asian.[150] 29% of Generation Z are children of immigrants or immigrants themselves, compared to 23% of Millennials when they were at the same age.[151]

Members of Generation Z are slightly less likely to be foreign-born than Millennials;[152] the fact that more American Latinos were born in the U.S. rather than abroad plays a role in making the first wave of Generation Z appear better educated than their predecessors. However, researchers warn that this trend could be altered by changing immigration patterns and the younger members of Generation Z choosing alternate educational paths.[153] As a demographic cohort, Generation Z is smaller than the baby boomers and their children, the Millennials.[154] According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Generation Z makes up about one quarter of the U.S. population, as of 2015.[155] There was an 'echo boom' in the 2000s, which certainly increased the absolute number of future young adults, but did not significantly change the relative sizes of this cohort compared to their parents.[156]

According to a 2022 Gallup survey, 20.8%, or about one in five members of Gen Z identify as LGBTQ+.[157]

- Population pyramids of Canada, the United States, and Mexico in 2016

Economic trends

Consumption

As consumers, members of Generation Z are typically reliant to the Internet to research their options and to place orders. They tend to be skeptical and will shun firms whose actions and values are contradictory.[158][159] Their purchases are heavily influenced by trends promoted by "influencers" on social media,[160][161] as well as the fear of missing out (FOMO) and peer pressure.[162] The need to be "trendy" is a prime motivator.[161] Due to their relatively high income, Generation Z have higher spending habits. According to new research, they rely on social media to make purchasing decisions, with health and beauty products being the most consumed category on these platforms.[163]

In the West, while majorities might signal their support for certain ideals such as "environmental consciousness" to pollsters, actual purchases do not reflect their stated views, as can be seen from their high demand for cheap but not durable clothing ("fast fashion"), or preference for rapid delivery.[158][159][160] Despite their socially progressive views, large numbers are still willing to purchase these items when human rights abuses in the developing countries that produce them are brought up.[161] However, young Western consumers of this cohort are less likely to pay a premium for what they want compared to their counterparts from emerging economies.[158][159]

In the United Kingdom, Generation Z's general avoidance of alcohol and tobacco has noticeably reduced government revenue in the form of the 'sin tax'.[164] Indeed, many young Britons remain dependent on their parents to pay their bills in a stagnant economy and about a quarter spends virtually nothing on luxuries.[165]

Employment

According to the International Labor Organization (ILA), the COVID-19 pandemic has amplified youth unemployment, but unevenly. By 2022, youth unemployment stood at 12.7% in Africa, 20.5% in Latin America, and 8.3% in North America.[166]

In the early 2020s, Chinese youths find themselves struggling with job hunting. University education offers little help.[167] In fact, due to the mismatch between education and the job market, those with no university qualifications are less likely to be unemployed.[168] By June 2023, China's unemployment rate for people aged 16 to 24 was about one fifth.[169]

In Germany, some public officials are recommending shorter work weeks at the same salary levels in spite of the struggling German economy. The situation is similar in other European countries.[170] In the United Kingdom, Generation Z is facing a gig economy with precarious prospects and stagnant wages.[165]

In the United States, the youth unemployment rate (16–24) was 7.5% in May 2023, the lowest in 70 years.[171] American high-school graduates could join the job market right away,[172] with employers offering them generous bonuses, high wages, and apprenticeship programs in order to offset the ongoing labor shortage.[173] Generation Z in the United States are projected to be the wealthiest generation compared to previous generations at the same age. The average individual has an annual salary that is $40,000 higher than that of previous generations.[174]

Education

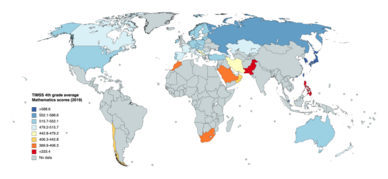

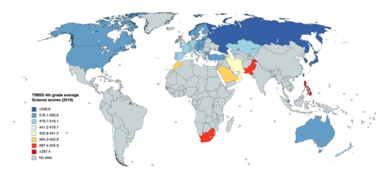

Since the mid-20th century, enrollment rates in primary schools has increased significantly in developing countries.[175] In 2019, the OECD completed a study showing that while education spending was up 15% over the previous decade, academic performance had stagnated.[47] Results from Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) in 2019 showed that the highest-scoring students in mathematics came from Asian polities and Russia.[47] The OECD's Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests administered in 2022 unveiled the continuation of a long-term decline in reading and mathematical skills since the early 2010s. In other words, the COVID-19 pandemic was only one contributing factor.[176] Even so, fifteen-year-old students (tenth graders) from Singapore, Macau, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan were largely unaffected or even saw an improvement. Once high-performing European countries—Iceland, Sweden, and Finland—continued their years-long decline. The U.S. national average remained behind those of other industrialized nations.[177][178]

By 2024, many places around the world have decided to ban the use of mobile phones in the classroom to help their students concentrate better.[179]

Different nations and territories approach the question of how to nurture gifted students differently. During the 2000s and 2010s, whereas the Middle East and East Asia (especially China, Hong Kong, and South Korea) and Singapore actively sought them out and steered them towards top programs, Europe and the United States had in mind the goal of inclusion and chose to focus on helping struggling students. In 2010, for example, China unveiled a decade-long National Talent Development Plan to identify able students and guide them into STEM fields and careers in high demand; that same year, England dismantled its National Academy for Gifted and Talented Youth and redirected the funds to help low-scoring students get admitted to elite universities.[46] Developmental cognitive psychologist David Geary observed that Western educators remained "resistant" to the possibility that even the most talented of schoolchildren needed encouragement and support and tended to concentrate on low performers. In addition, even though it is commonly believed that past a certain IQ benchmark (typically 120), practice becomes much more important than cognitive abilities in mastering new knowledge, recently published research papers based on longitudinal studies, such as the Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth (SMPY) and the Duke University Talent Identification Program, suggest otherwise.[46]

Since the early 2000s, the number of students from emerging economies going abroad for higher education has risen markedly. This was a golden age of growth for many Western universities admitting international students.[180] In the late 2010s, around five million students traveled abroad each year for higher education, with the developed world being the most popular destinations and China the biggest source of international students.[180] In 2019, the United States was the most popular destination for international students, with 30% of its international student body coming from mainland China, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Japan.[181] Among children of the Chinese ruling class ("princelings"), attending elite institutions in the United States was commonplace and seen as a status symbol,[182] but the deterioration of Sino-American relations as exemplified by President Donald Trump's entry restrictions on Chinese students in addition to the complications produced by the COVID-19 pandemic reduced the number of Chinese students enrolling in many American colleges and universities.[183][180] But even before the pandemic, undergraduate and graduate enrollments of native-born American citizens have both been in decline,[184][185] while trade schools continue to attract growing numbers of students due to a shortage of high-skilled blue-collar workers.[186][187] Since the 2000s, numerous institutions of higher learning have permanently closed.[188][189] These trends have led to the speculation of the deflation of the higher-education bubble in the United States.[183][180] But among the top colleges and universities, there is still growth in the number of applicants.[190] This is due partly to students sending their applications to more schools for a chance of getting admitted[191] and because these institutions have not significantly expanded their capacities.[192] Moreover, international enrollment for the 2022–2023 academic year in American institutions of higher learning exceeded pre-pandemic levels, fueled by a surge of students from India and sub-Saharan Africa.[193] Nevertheless, dependency on foreign students is threatening the future of many American schools, which had hitherto been assuming that the number of international applicants would keep growing.[194] Meanwhile, in Canada, the government has cut the number of international student visas granted each year in response to growing public disapproval of current levels of immigration.[195]

Because China's expansion of higher education was done for political rather than economic reasons, the country is currently overproducing university graduates, who are struggling to find white-collar jobs that match their education.[196] In 2023, as many as one in five Chinese graduates struggled to find gainful employment.[197] Enrollment in higher education was just under 60% during the early 2020s, compared to around 40% in the United States.[196]

Health issues

Mental

In general, teenagers and young adults are especially vulnerable to depression and anxiety due to the changes to the brain during adolescence.[198] A 2020 meta-analysis found that the most common psychiatric disorders among adolescents were ADHD, anxiety disorders, behavioral disorders, and depression, consistent with a previous one from 2015.[37] Data from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) indicate that while the percentages of teenagers reporting mental-health issues (such as psychological distress and loneliness) remained approximately the same during the 2000s, they steadily increased during the 2010s.[199] While the COVID-19 pandemic has damaged the mental health of people of all ages, the increase was most noticeable for people aged 15 to 24. A 2021 meta-analysis suggests that globally, the most likely age for the onset of depressive disorder is 19.5 years and generalized anxiety disorder is 15.5 years.[198] A 2021 UNICEF report stated that 13% of ten- to nineteen-year-olds around the world had a diagnosed mental health disorder whilst suicide was the fourth most common cause of death among fifteen- to nineteen-year-olds. It commented that "disruption to routines, education, recreation, as well as concern for family income, health and increase in stress and anxiety, [caused by the COVID-19 pandemic] is leaving many children and young people feeling afraid, angry and concerned for their future." It also noted that the pandemic had widely disrupted mental health services.[200] Anxiety over climate change has compounded the problem.[201] Though males remain more likely than females to commit suicide, the prevalence of suicide among teenage girls has risen significantly during the 2010s in many countries.[202] For example, data from the British National Health Service (NHS) showed that in England, hospitalizations for self-harm doubled among teenage girls between 1997 and 2018, but there was no parallel development among boys.[32] Whether or not this can be attributed to the use of smartphones and social media networks remains debated, however.[202]

In some Western countries—Australia, the Netherlands, Spain, the United Kingdom, and parts of the United States—intervention programs have been set up to prevent depression among teenagers. However, funding has been limited as governments tend to focus on the here and now rather than preventing problems from arising in the future.[198]

Sleep deprivation

Sleep deprivation is on the rise among contemporary youths,[203][34] due to a combination of poor sleep hygiene (having one's sleep disrupted by noise, light, and electronic devices), caffeine intake, beds that are too warm, a mismatch between biologically preferred sleep schedules at around puberty and social demands, insomnia, growing homework load, and having too many extracurricular activities.[34][35] Consequences of sleep deprivation include low mood, worse emotional regulation, anxiety, depression, increased likelihood of self-harm, suicidal ideation, and impaired cognitive functioning.[34][35] In addition, teenagers and young adults who prefer to stay up late tend to have high levels of anxiety, impulsivity, alcohol intake, and tobacco smoking.[204]

A study by Glasgow University found that the number of schoolchildren in Scotland reporting sleep difficulties increased from 23% in 2014 to 30% in 2018. 37% of teenagers were deemed to have low mood (33% males and 41% females), and 14% were at risk of depression (11% males and 17% females). Older girls faced high pressure from schoolwork, friendships, family, career preparation, maintaining a good body image and good health.[205]

In Canada, teenagers sleep on average between 6.5 and 7.5 hours each night, much less than what the Canadian Paediatric Society recommends, 10 hours.[206] According to the Canadian Mental Health Association, only one out of five children who needed mental health services received it. In Ontario, for instance, the number of teenagers getting medical treatment for self-harm doubled in 2019 compared to ten years prior. The number of suicides has also gone up. Various factors that increased youth anxiety and depression include over-parenting,[207] perfectionism (especially with regards to schoolwork),[208] social isolation, social-media use, financial problems, housing worries, and concern over some global issues such as climate change.[209]

Cognitive abilities

A 2010 meta-analysis by an international team of mental health experts found that the worldwide prevalence of intellectual disability (ID) was around one percent. But the share of individuals with such a condition in low- to middle-income countries were up to twice as high as their wealthier counterparts because they lacked the sources needed to tackle the problem, such as preventing children from being born with ID due to hereditary conditions with antenatal genetic screening, poor child and maternal care facilities, and inadequate nutrition, leading to, for instance, iodine deficiency. The researchers also found that ID was more common among children and adolescents than adults.[36] A 2020 literature review and meta-analysis confirmed that the incidence of ID was indeed more common than estimates from the early 2000s.[37]

In 2013, a team of neuroscientists from the University College London published a paper on how neurodevelopmental disorders can affect a child's educational outcome. They found that up to 10% of the human population have specific learning disabilities or about two to three children in a (Western) classroom. Such conditions include dyscalculia, dyslexia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and autism spectrum disorder. They are caused by abnormal brain development due to complicated environmental and genetic factors. A child may have multiple learning disorders at the same time. For example, among children with ADHD, 33-45% also have dyslexia and 11% have dyscalculia. Normal or high levels of intelligence offer no protection. Each child has a unique cognitive and genetic profile and would benefit from a flexible education system.[210][211]

A 2017 study from the Dominican Republic suggests that students from all sectors of the educational system utilize the Internet for academic purposes, yet those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds tend to rank the lowest in terms of reading comprehension skills.[212]

A 2020 report by psychologist John Protzko analyzed over 30 studies and found that children have become better at delaying gratification over the previous 50 years, corresponding to an average increase of 0.18 standard deviations per decade on the IQ scale. This is contrary to the opinion of the majority of the 260 cognitive experts polled (84%), who thought this ability was deteriorating. Researchers test this ability using the Marshmallow Test. Children are offered treats: if they are willing to wait, they get two; if not, they only get one. The ability to delay gratification is associated with positive life outcomes, such as better academic performance, lower rates of substance use, and healthier body weights. Possible reasons for improvements in the delaying gratification include higher standards of living, better-educated parents, improved nutrition, higher preschool attendance rates, more test awareness, and environmental or genetic changes. This development does not mean that children from the early 20th century were worse at delaying gratification and those from the late 21st will be better at it, however. Moreover, some other cognitive abilities, such as simple reaction time, color acuity, working memory, the complexity of vocabulary usage, and three-dimensional visuospatial reasoning have shown signs of secular decline.[17]

In a 2018 paper, cognitive scientists James R. Flynn and Michael Shayer argued that the observed gains in IQ during the 20th century—commonly known as the Flynn effect—had either stagnated or reversed, as can be seen from a combination of IQ and Piagetian tests. In the Nordic nations, there was a clear decline in general intelligence starting in the 1990s, an average of 6.85 IQ points if projected over 30 years. In Australia and France, the data remained ambiguous; more research was needed. In the United Kingdom, young children experienced a decline in the ability to perceive weight and heaviness, with heavy losses among top scorers. In German-speaking countries, young people saw a fall in spatial reasoning ability but an increase in verbal reasoning skills. In the Netherlands, preschoolers and perhaps schoolchildren stagnated (but seniors gained) in cognitive skills. What this means is that people were gradually moving away from abstraction to concrete thought. On the other hand, the United States continued its historic march towards higher IQ, a rate of 0.38 per decade, at least up until 2014. South Korea saw its IQ scores growing at twice the average U.S. rate. The secular decline of cognitive abilities observed in many developed countries might be caused by diminishing marginal returns due to industrialization and to intellectually stimulating environments for preschoolers, the cultural shifts that led to frequent use of electronic devices, the fall in cognitively demanding tasks in the job market in contrast to the 20th century, and possibly dysgenic fertility.[213]

Physical

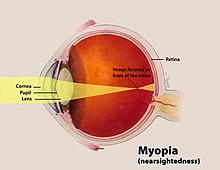

A 2015 study found that the frequency of nearsightedness has doubled in the United Kingdom within the last 50 years. Ophthalmologist Steve Schallhorn, chairman of the Optical Express International Medical Advisory Board, noted that research has pointed to a link between the regular use of handheld electronic devices and eyestrain. The American Optometric Association sounded the alarm in a similar vein.[214] According to a spokeswoman, digital eyestrain, or computer vision syndrome, is "rampant, especially as we move toward smaller devices and the prominence of devices increase in our everyday lives." Symptoms include dry and irritated eyes, fatigue, eye strain, blurry vision, difficulty focusing, headaches. However, the syndrome does not cause vision loss or any other permanent damage. To alleviate or prevent eyestrain, the Vision Council recommends that people limit screen time, take frequent breaks, adjust the screen brightness, change the background from bright colors to gray, increase text sizes, and blinking more often. Parents should not only limit their children's screen time but should also lead by example.[215]

While food allergies have been observed by doctors since ancient times and virtually all foods can be allergens, research by the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota found they have been growing increasingly common since the early 2000s. Today, one in twelve American children has a food allergy, with peanut allergy being the most prevalent type. Reasons for this remain poorly understood.[29] Nut allergies in general have quadrupled and shellfish allergies have increased 40% between 2004 and 2019. In all, about 36% of American children have some kind of allergy. By comparison, this number among the Amish in Indiana is 7%. Allergies have also risen ominously in other Western countries. In the United Kingdom, for example, the number of children hospitalized for allergic reactions increased by a factor of five between 1990 and the late 2010s, as did the number of British children allergic to peanuts. In general, the better developed the country, the higher the rates of allergies.[30] Reasons for this remain poorly understood.[29] One possible explanation, supported by the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, is that parents keep their children "too clean for their own good". They recommend exposing newborn babies to a variety of potentially allergenic foods, such as peanut butter before they reach the age of six months. According to this "hygiene hypothesis", such exposures give the infant's immune system some exercise, making it less likely to overreact. Evidence for this includes the fact that children living on a farm are consistently less likely to be allergic than their counterparts who are raised in the city, and that children born in a developed country to parents who immigrated from developing nations are more likely to be allergic than their parents are.[30]

A research article published in 2019 in the journal The Lancet reported that the number of South Africans aged 15 to 19 being treated for HIV increased by a factor of ten between 2010 and 2019. This is partly due to improved detection and treatment programs. However, less than 50% of the people diagnosed with HIV went onto receive antiviral medication due to social stigma, concerns about clinical confidentiality, and domestic responsibilities. While the annual number of deaths worldwide due to HIV/AIDS has declined from its peak in the early 2000s, experts warned that this venereal disease could rebound if the world's booming adolescent population is left unprotected.[216]

Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics reveal that 46% of Australians aged 18 to 24, about a million people, were overweight in 2017 and 2018. That number was 39% in 2014 and 2015. Obese individuals face higher risks of type II diabetes, heart disease, osteoarthritis, and stroke. The Australian Medical Associated and Obesity Coalition have urged the federal government to levy a tax on sugary drinks, to require health ratings, and to regulate the advertisement of fast foods. In all, the number of Australian adults who are overweight or obese rose from 63% in 2014–15 to 67% in 2017–18.[217]

Puberty

In Europe and the United States, the average age of the onset of puberty among girls was around 13 in the early 21st century, down from about 16 a hundred years earlier. Early puberty is associated with a variety of mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression (as people at this age tend to strongly desire conformity with their peers), early sexual activity, substance use, tobacco smoking, eating disorders, and disruptive behavioral disorders.[24] Girls who mature early also face higher risks of sexual harassment. Moreover, in some cultures, pubertal onset remains a marker of readiness for marriage, for, in their point of view, a girl who shows signs of puberty might engage in sexual intercourse or risk being assaulted, and marrying her off is how she might be 'protected'.[25] To compound matters, factors known for prompting mental health problems are themselves linked to early pubertal onset; these are early childhood stress, absent fathers, domestic conflict, and low socioeconomic status. Possible causes of early puberty could be positive, namely improved nutrition, or negative, such as obesity and stress.[24] Other triggers include genetic factors, high body-mass index (BMI), exposure to endocrine-disrupting substances that remain in use, such as Bisphenol A (found in some plastics) and dichlorobenzene (used in mothballs and air deodorants), and to banned but persistent chemicals, such as dichlorodiphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT) and dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), and perhaps a combination thereof (the 'cocktail effect').[28][218]

A 2019 meta-analysis and review of the research literature from all inhabited continents found that between 1977 and 2013, the age of pubertal onset among girls has fallen by an average of almost three months per decade, but with significant regional variations, ranging from 10.1 to 13.2 years in Africa to 8.8 to 10.3 years in the United States. This investigation relies on measurements of thelarche (initiation of breast tissue development) using the Tanner scale rather than self-reported menarche (first menstruation) and MRI brain scans for signs of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis being reactivated.[28] Furthermore, there is evidence that sexual maturity and psychosocial maturity no longer coincide; 21st-century youth appears to be reaching the former before the latter. Neither adolescents nor societies are prepared for this mismatch.[26][27][g]

Political views and participation

-

Youths protest in Toronto as part of the School Strike for Climate movement in 2019.

-

A University of Hong Kong student holds up a blank piece of paper to show support for the people in mainland China protesting against the COVID lockdown in 2022.

-

Amir Kabir University of Technology students protest against the hijab and the government in the aftermath of the death of Mahsa Amini at the hands of the Iranian morality police for allegedly violating the hijab code, 2022.

-

Bangladesh's Student–People's uprising is dubbed as world's first successful Gen Z revolution that ended Sheikh Hasina's 15-year-long autocratic rule.

-

Greta Thunberg is a climate activist born in Sweden in 2003.

Among developed democracies, young people's faith in the institutions, including their own government, has declined compared to that of previous generations.[131] In tandem with more members of Generation Z being able to vote in elections during the late 2010s and early 2020s, the youth vote has increased in both Europe and the United States.[219][220] An early political movement primarily driven by Generation Z was School Strike for Climate of the late 2010s. The movement involved millions of young people around the world who followed the footsteps of Swedish activist Greta Thunberg to skip school in order to protest in favor of greater action on climate change.[221][222] Around the world, large numbers of people from this cohort feel angry, anxious, guilty, helpless, and sad about climate change and are dissatisfied with how their governments have responded so far.[201] However, their consumption choices (see above) reveal a gap between their stated values and their activism.[159][160][161]

Polling on immigration in various countries receives mixed responses from Generation Z.[223][224] In Europe, voters from Generation Z swung from favoring the Greens in the 2019 European Parliament elections to supporting parties of the (far) right in 2024.[225] In the United States, Generation Z's politics are largely similar to those of Millennials in that they tend to be more left-wing than preceding cohorts.[226][227] However, polls consistently show that the Democratic Party has been steadily hemorrhaging support among young adults during the late 2010s and early 2020s, even though they largely disapprove of the Republican Party.[228][229][230] By the early 2020s, young voters in Europe have become increasingly concerned about the rising cost of living, violent crime, declining public services in rural areas, immigration, and the Russo-Ukrainian War.[225] In the United States, the single most important issue for Generation Z is the economy (including inflation; the costs of housing, healthcare, and higher education; income inequality; and taxes).[231][232] Political scientist Jean-Yves Camus dismissed the stereotype of young people altruistically voting for green or left-wing parties as misguided and outdated.[225]

Nevertheless, these broad trends conceal a significant gender divide across the Western world, with young women (under 30) being vocally left-leaning and young men being fiercely right-leaning on a variety of issues from immigration to sexual harassment.[233][234] Furthermore, a backlash against feminism among young men is quite strong in many countries; older men tend to hold similar views to women across age groups on this topic. Possible causes for this phenomenon include the general tendency for women to become better educated than men and the polarizing nature of social media sites. This sex gap has been noticeable since the 2000s, but has widened since the mid-2010s. This growing difference has also been observed among young adults in China and South Korea.[235]

Members of Generation Z who are active in politics are more likely than their elders to avoid buying from or working for companies that do not share their sociopolitical views, and they take full advantage of the Internet as activists.[131] Consequently, maintaining a presence on social media networks, especially TikTok, is vital for politicians and political parties dependent upon the youth vote.[225][227][230]

In Bangladesh, the young students of Generation Z protested against Sheikh Hasina's authoritarian rule due to the reinstatement of the pre-2018 quota system in government jobs and later the mass killing done by the government. Eventually, they overthrew Shiekh Hasina's government, ending its 15-year long authoritarian rule. These protests are dubbed as world's first successful "Gen Z Revolution".[236]

Religious tendencies

In the West, Generation Z is the least religious generation in history.[237][238][239] More members of Generation Z describe themselves as nonbelievers than any previous generation and reject religious affiliation, though many of them still describe themselves as spiritual.[239] In the United States, Generation Z has twice as many self-identified atheists as prior generations.[240]

The 2016 British Social Attitudes Survey found that 71% of people between the ages of 18 and 24 had no religion, compared to 62% the year before. A 2018 ComRes survey found that slightly more than one in two of those aged 18 to 24 reported a positive experience with Christians and Christianity. Two-thirds of the same age group have never attended church; among the remaining third, 20% went a few times a year, and 2% multiple times per week. 12% of respondents aged 18 to 24 agreed with the claim that Christians were a bad influence on society, compared to just over half who disagreed. For comparison, 14% of those aged 25 to 34 agreed. In all, 51% of Britons disagreed with the same while 10% agreed.[241] According to British Office for National Statistics (ONS), people under the age of 40 in England and Wales are more likely to consider themselves irreligious rather than Christian.[242]

Risky behaviors

Adolescent pregnancy

Adolescent pregnancy has been in decline during the early 21st century all across the industrialized world, due to the widespread availability of contraception and the growing avoidance of sexual intercourse among teenagers.[243] In the European Union and the United Kingdom, teenage parenthood has fallen 58% and 69%, respectively, between the 1990s and the 2020s.[244] In New Zealand, the pregnancy rate for females aged 15 to 19 dropped from 33 per 1,000 in 2008 to 16 in 2016. Highly urbanized regions had adolescent pregnancy rates well below the national average whereas Māori communities had much higher than average rates. In Australia, it was 15 per 1,000 in 2015.[243] In the United States, teenage pregnancy rates continued to decline, reaching 13.5 in 2022, the lowest on record.[245] Northern European countries, above all the Netherlands, have some of the world's lowest teenage pregnancy and abortion rates by implementing thorough sex education.[246]

Alcoholism and substance use

2020 data from the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) showed on a per-capita basis, members of Generation Z binged on alcohol 20% less often than Millennials. However, 9.9% of people aged 16 to 24 consumed at least one drug in the past month, usually cannabis, or more than twice the share of the population between the ages of 16 and 59. "Cannabis has now taken over from the opiates in terms of the most people in treatment for addiction," psychopharmacologist Val Curran of the University College London (UCL) told The Telegraph. Moreover, the quality and affordability of various addictive drugs have improved in recent years, making them an appealing alternative to alcoholic beverages for many young people, who now have the ability to arrange a meeting with a dealer via social media. Addiction psychiatrist Adam Winstock of UCL found using his Global Drug Survey that young people rated cocaine more highly than alcohol on the basis of value for money, 4.8 compared to 4.7 out of 10.[14]

As of 2019, cannabis was legal for both medical and recreational use in Uruguay, Canada, and 33 states in the US.[247] In the United States, Generation Z is the first to be born into a time when the legalization of marijuana at the federal level is being seriously considered.[248] While adolescents (people aged 12 to 17) in the late 2010s were more likely to avoid both alcohol and marijuana compared to their predecessors from 20 years before, college-aged youths are more likely than their elders to consume marijuana.[13] Marijuana use in Western democracies was three times the global average, as of 2012, and in the U.S., the typical age of first use is 16.[249] This is despite the fact that marijuana use is linked to some risks for young people,[247][250] such as in the impairment of cognitive abilities and school performance, though a causality has not been established in this case.[251]

Youth crime

During the 2010s, when most of Generation Z experienced some or all of their adolescence, reductions in youth crime were seen in some Western countries. A report looking at statistics from 2018 to 2019 noted that the numbers of young people aged ten to seventeen in England and Wales being cautioned or sentenced for criminal activity had fallen by 83% over the previous decade, while those entering the youth justice system for the first time had fallen by 85%.[252] In 2006, 3,000 youths in England and Wales were detained for criminal activity; ten years later, that number fell below 1,000.[11] In Europe, teenagers were less likely to fight than before.[11] Research from Australia suggested that crime rates among adolescents had consistently declined between 2010 and 2019.[253]

In a 2014 report, Statistics Canada stated that police-reported crimes committed by persons between the ages of 12 and 17 had been falling steadily since 2006 as part of a larger trend of decline from a peak in 1991. Between 2000 and 2014, youth crimes plummeted 42%, above the drop for overall crime of 34%. In fact, between the late 2000s and mid-2010s, the fall was especially rapid. This was primarily driven by a 51% drop in theft of items worth no more than CAN$5,000 and burglary. The most common types of crime committed by Canadian adolescents were theft and violence. At school, the most frequent offenses were possession of cannabis, common assault, and uttering threats. Overall, although they made up only 7% of the population, adolescents stood accused of 13% of all crimes in Canada. In addition, mid- to late-teens were more likely to be accused of crimes than any other age group in the country.[254]

Family and social life

Upbringing

Parents increasingly realize that in order to ensure their children have the best future attainable, they must have fewer of them and invest more resources per child.[256] Sociologists Judith Treas and Giulia M. Dotti Sani analyzed the diaries of 122,271 parents (68,532 mothers and 53,739 fathers) aged 18 to 65 in households with at least one child below the age of 13 from 1965 to 2012 in eleven Western countries—Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States, Spain, Italy, France, the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, Norway, and Slovenia—and discovered that in general, parents had been spending more and more time with their children. In 2012, the average mother spent twice as much time with her offspring than her counterpart in 1965. Among fathers, the average amount of time quadrupled. Nevertheless, women were still the primary caregivers. Parents of all education levels were represented, though those with higher education typically spent much more time with their children, especially university-educated mothers. France was the only exception. French mothers were spending less time with their children whereas fathers were spending more time. This overall trend reflected the dominant ideology of "intensive parenting"—the idea that the time parents spend with children is crucial for their development in various areas and the fact that fathers developed more egalitarian views with regards to gender roles over time and became more likely to want to play an active role in their children's lives.[255]

In the United Kingdom, there was a widespread belief in the early 21st century that rising parental, societal and state concern for the safety of children was leaving them increasingly mollycoddled and slowing the pace they took on responsibilities.[257][258][259] The same period saw a rise in child-rearing's position in the public discourse with parenting manuals and reality TV programs focused on family life, such as Supernanny, providing specific guidelines for how children should be cared for and disciplined.[260]

According to Statistics Canada, the number of households with both grandparents and grandchildren remained rare but grew in the early 21st century. In 2011, five percent of Canadian children below the age of ten lived with a grandparent, up from 3.3% in the previous decade. This is in part because Canadian parents in the early 21st century could not (or believe they could not) afford childcare and often find themselves having to work long hours or irregular shifts. Meanwhile, many grandparents struggled to keep up with their highly active grandchildren on a regular basis due to their age. Because Millennials and members of Generation X tend to have fewer children than their parents the baby boomers, each child typically receives more attention from grandparents and parents compared to previous generations.[261]

Friendships and socialization

According to the OECD PISA surveys, 15-year-olds in 2015 had a tougher time making friends at school than ten years prior. European teenagers were becoming more and more like their Japanese and South Korean counterparts in social isolation. This might be due to intrusive parenting, heavy use of electronic devices, and concerns over academic performance and job prospects.[11]

A study of social interaction among American teenagers found that the amount of time young people spent with their friends had been trending downwards since the 1970s but fallen into especially sharp decline after 2010. The percentage of students in the 12th grade (typically 17 to 18 years old) who said they met with their friends almost every day fell from 52% in 1976 to 28% in 2017. The percentage of that age group who said they often felt lonely (which had fallen during the early 2000s) increased from 26% in 2012 to 39% in 2017 whilst the percentage who often felt left out increased from 30% to 38% over the same period. Statistics for slightly younger teenagers suggested that parties had become significantly less common since the 1980s.[262]

Romance and marriage

According to a 2014 report from UNICEF, some 250 million females were forced into marriage before the age of 15, especially in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Problems faced by child brides include loss of educational opportunity, less access to medical care, higher childbirth mortality rates, depression, and suicidal ideation.[25][263]

In Australia, it was reported in 2017 that growing numbers of older teenage boys and young men were avoiding romantic relationships altogether, citing concerns over the traumatic experiences of older male family members, including false accusations of sexual misconduct or loss of assets and money after a divorce. This social trend—Men Going Their Own Way (MGTOW)—is an outgrowth of the men's rights movement, but one that emphasizes detachment from women as a way to deal with the issues men face. "Both sexes have different challenges; we've lost sight of that. We're stuck in a gender war and it's harming our children", psychologist Meredith Fuller told News.com.au.[264]

In China, young people nowadays are much more likely to deem marriage and children sources of stress rather than fulfillment, going against the Central Government's attempts to increase the birth rate. Women born between the mid-1990s to about 2010 are less interested in getting married than men their own age. As a result of the one-child policy, young Chinese women have become more educated and financially independent than ever before, and this has led to a shift in public attitudes towards career-oriented women. The "lying flat" movement, popular among Chinese youths, also extends to the domain of marriage and child-rearing.[265] According to a 2021 survey by the Communist Youth League, 44% of young urban women and 25% of urban young men said they were not planning on getting married. When asked why, majorities said they had trouble finding the right person, cited the high costs of marriage, or told the pollsters they simply did not believe in marriage.[266]

Children and parenthood

In line with a fall in adolescent pregnancy in the developed world, which is discussed in more detail elsewhere in this article, there has also been a reduction in the percentage of the youngest adults with children. The Office for National Statistics has reported that the number of babies being born in the United Kingdom to 18 year old mothers had fallen by 58% from 2000 to 2016 and the amount being born to 18 year old fathers had fallen by 41% over the same period.[267] Pew Research reports that in 2016, 88% of American women aged 18 to 21 were childless as opposed to 80% of Generation X and 79% of millennial female youth at a similar age.[268]

A 2020 survey conducted by PensionBee in the United Kingdom found that about 10% of non-parents aged 18 to 23 were considering not having children in order to be able to retire earlier. Those in the arts and those in the income bracket £25,001 to £55,000 were most likely to say no to having children.[269]

Over half of Chinese youths aged 18 to 26 said they were uninterested in having children because of the high cost of child-rearing, according to a 2021 poll by the Communist Youth League.[266]

Food choices

The food choices made by Generation Z reflect the generation's concerns about climate, sustainability, and animal welfare. A study by catering firm Aramark found 79% of members of the generation would go meatless between once and twice a week.[270] The generation is considered the most interested in plant-based and vegan food choices, which they see as equal to other food types. As Generation Z's purchasing power grows, so does the amount of vegan and vegetarian food they eat.[271] Generation Z sees dining out with friends and sharing small plates of food as exciting and interesting. According to 2022 Ernst & Young data, plant-based meat, cultured meat, and fermented meat are forecast to grow to 40% of the market by volume by 2040 in the United States. Plant-based meat is widely available in supermarkets and restaurants, but cultured and fermented meats (which are made without slaughtering animals) are not commercially available but are now being developed by companies.[272]

Use of information and communications technologies (ICT)

Use of ICT in general

Generation Z is one of the first cohorts to have Internet technology readily available at a young age.[273] With the Web 2.0 revolution that occurred throughout the mid-late 2000s and 2010s, they have been exposed to an unprecedented amount of technology in their upbringing, with the use of mobile devices growing exponentially over time. Anthony Turner characterizes Generation Z as having a "digital bond to the Internet", and argues that it may help youth to escape from emotional and mental struggles they face offline.[6]

According to U.S. consultants Sparks and Honey in 2014, 41% of Generation Z spend more than three hours per day using computers for purposes other than schoolwork, compared with 22% in 2004.[274] In 2015, an estimated 150,000 apps, 10% of apps in Apple's App Store, were educational and aimed at children up to college level,[275] though opinions are mixed as to whether the net result will be deeper involvement in learning[275] and more individualized instruction, or impairment through greater technology dependence[276] and a lack of self-regulation that may hinder child development.[276] Parents who raise Gen Z children fear the overuse of the Internet, and dislike the ease of access to inappropriate information and images, as well as social networking sites where minors can gain access to people worldwide. Gen Z children, inversely, feel annoyed with their parents and complain about parents being overly controlling when it comes to their Internet usage.[277]

A 2015 study by Microsoft found that 77% of respondents aged 18 to 24 said yes to the statement, "When nothing is occupying my attention, the first thing I do is reach for my phone," compared to just 10% for those aged 65 and over.[278]

In a TEDxHouston talk, Jason Dorsey of the Center for Generational Kinetics stressed the notable differences in the way that Millennials and Generation Z consume technology, with 18% of Generation Z feeling that it is okay for a 13-year-old to have a smartphone, compared with just 4% for the previous generation.[279][280][281] An online newspaper about texting, SMS and MMS writes that teens own cellphones without necessarily needing them; that receiving a phone is considered a rite of passage in some countries, allowing the owner to be further connected with their peers, and it is now a social norm to have one at an early age.[282] An article from the Pew Research Center stated that "nearly three-quarters of teens have or have access to a smartphone and 30% have a basic phone, while just 12% of teens 13 to 15 say they have no cell phone of any type".[283] These numbers are only on the rise and the fact that the majority own a cell phone has become one of this generation's defining characteristics. Consequently, "24% of teens go online 'almost constantly'."[283]

A survey of students from 79 countries by the OECD found that the amount of time spent using an electronic device has increased, from under two hours per weekday in 2012 to close to three in 2019, at the expense of extracurricular reading.[38]

Psychologists have observed that sexting, the transmission of sexually explicit content via electronic devices, has seen noticeable growth among contemporary adolescents. Older teenagers are more likely to participate in sexting. Besides some cultural and social factors such as the desire for acceptance and popularity among peers, the falling age at which a child receives a smartphone may contribute to the growth in this activity. However, while it is clear that sexting has an emotional impact on adolescents, it is still not clear how it precisely affects them. Some consider it a high-risk behavior because of the ease of dissemination to third parties leading to reputational damage and the link to various psychological conditions including depression and even suicidal ideation. Others defend youths' freedom of expression over the Internet. There is some evidence that at least in the short run, sexting brings positive feelings of liveliness or satisfaction. However, girls are more likely than boys to be receiving insults, social rejections, or reputational damage as a result of sexting.[18]

Digital literacy

Despite being labeled as digital natives, the 2018 International Computer and Information Literacy Study (ICILS), conducted on 42,000 eighth-graders (or equivalents) from 14 countries and education systems, found that only two percent of these people were sufficiently proficient with information devices to justify that description, and only 19% could work independently with computers to gather information and to manage their work.[7] ICILS assesses students on two main categories: Computer and Information Literacy (CIL), and Computational Thinking (CT). Countries or education systems whose students scored near or above the international average of 496 in CIL were, in increasing order, France, North Rhine-Westphalia, Portugal, Germany, the United States, Finland, South Korea, Moscow, and Denmark. Countries or education systems whose students scored near or above the international average of 500 were, in increasing order, the United States, France, Finland, Denmark, and South Korea.[284]

By the early 2020s, many members of Generation Z were entering the (digital) work place without some basic ICT skills,[8] such as touch typing,[9] though they can learn more quickly than older workers.[8]

Pornography viewing