Yosimar Reyes

Yosimar Reyes | |

|---|---|

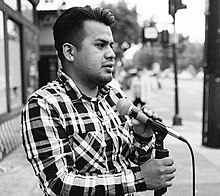

Reyes in 2015 | |

| Born | September 22, 1988 Guerrero, Mexico |

| Occupation | Poet, Performer, Activist, Public Intellectual |

| Language | English, Spanish |

| Alma mater | San Francisco State University |

| Years active | 2004 - present |

| Notable works | For Colored Boys Who Speak Softly, Prieto |

| Website | |

| yosimarreyes | |

Yosimar Reyes (born September 22, 1988) is a Mexican-born poet and activist. He is a queer[1] undocumented immigrant who was born in Guerrero, Mexico, and raised in East San Jose, California. Reyes has been described as "a voice that shines light on the issues affecting queer immigrants in the U.S. and throughout the world."[2]

Reyes centers queer, working class, and immigrant themes in his work. He has been a guest speaker at numerous universities, community organizations, and cultural institutions including Stanford University, UCLA,[3] Princeton University,[4] the San Francisco Public Library,[5] the Park Avenue Armory,[6] the Aspen Institute,[7] the University of Pennsylvania,[8] Harvard University,[9] and the North American Literary and Cultural Studies department at Saarland University in Germany.[10]

As of 2024, Reyes is the inaugural Performing Artist in Residence at Movimiento de Arte y Cultura Latino Americana (MACLA), where he curates "performing arts programs [that uplift] the work of contemporary Chicanx/Latinx artists,"[11] Border Futures Artist at the Center for Cultural Power,[12] Creative Ambassador for the City of San José,[13] and 2024-25 Santa Clara County Poet Laureate.[14][15] From 2016 to 2018, he served as Arts Fellow at Define American,[16] a media and culture organization founded by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Jose Antonio Vargas which "uses the power of stories to [...] shift the conversation around immigrants, identity and citizenship in a changing America." He also previously served as Public Programs Coordinator at La Galería de la Raza in San Francisco.[17]

Early life and education

[edit]Reyes was born on September 22, 1988, in Atoyac de Álvarez, Guerrero, Mexico.[18] At age 3, he migrated to the United States with his family.[19] Raised in East San Jose,[20] he came out to his family and community at the age of 16.[21]

Reyes attended Latino College Preparatory Academy, where he was awarded his high school diploma in 2006.[22] After briefly attending Evergreen Valley College, he received a Bachelor of Arts in Creative Writing from San Francisco State University in 2015.[23]

Career

[edit]

Reyes began performing his poetry at 16 years old upon realizing the power of language after being called “joto,” a derogatory Spanish term used to refer to gay men.[24]

Reyes' first publication was the result of his winning first place in a writing competition in San Jose.[21] At age 17, he won the title for the 2005 South Bay Teen Grand SLAM Champion, repeating his win in 2006.[21] In 2007, he was featured in a Youth Speaks documentary titled 2nd Verse: the Rebirth of Poetry.[25]

In 2009, he self-published his first chapbook, For Colored Boys Who Speak Softly, which garnered national and international acclaim.[2] Musicians Carlos Santana and Harry Belafonte were early champions of Reyes' work.[26]

He has been anthologized in the collections Mariposas: A Modern Anthology of Queer Latino Poetry (Floricanto Press); Queer in Aztlán: Chicano Male Recollections of Consciousness and Coming Out (Cognella Press);[27] and Joto: An Anthology of Queer Xicano & Chicano Poetry (Kórima Press), and Somewhere We Are Human: Authentic Voices on Migration, Survival, and New Beginnings (HarperCollins).[28][29] He and his work have also been featured in The Atlantic,[30] the Huffington Post,[31] Medium,[32] Remezcla,[33] VICE,[34] and Teen Vogue.[35][36]

In June 2016, Reyes premiered a solo staged reading of Prieto, his first autobiographical play, in collaboration with Guerrilla Rep Theater, Galería de la Raza, and Define American.[37] In Prieto, Reyes recounts his younger self's understanding of his dual queer and undocumented identity.[38] Prieto premiered at the Brava Theater in San Francisco in September 2022,[39] and later toured to Movimiento de Arte y Cultura Latino Americana (MACLA),[40] and the Chicago Shakespeare Theater.[41]

Reyes was awarded an Undocupoets fellowship by Sibling Rivalry Press in 2017,[42] and an Emerging Writers' fellowship in playwriting by Lambda Literary in 2018.[43] Reyes' poem "Paisa" was featured in the eponymous short film directed by Dorian Wood and Graham Kolbeins in 2019.[44]

During the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, Reyes launched his virtual #YosiBookClub and IG Live Writers' Series wherein he interviews prominent Latino authors in an effort to demystify the creative process. Among interviewees have been celebrated Mexican-American journalist Maria Hinojosa, playwright and USC professor Luis Alfaro, Vida TV series creator Tanya Saracho, National Book Award finalist Kali Fajardo-Anstine, BuzzFeed contributor Curly Velasquez, former Goldman Sachs executive Julissa Arce, and noted poets Yesika Salgado, Karla Cornejo Villavicencio, Walter Thompson-Hernández, and Javier Zamora.[45][46]

In addition to his literary practice, Reyes has curated or participated in multidisciplinary art exhibitions, including Homegirrlz: Demos and Remixes, Migrating Sexualities: Unspoken Stories of Land, Body and Sex,[47] We Never Needed Papers to Thrive,[48] #UndocuJoy,[49] In Plain Sight[50] and Creatives in Place.[51][52] In 2020, Reyes was awarded a $25,000 Catalyst for Change grant from the National Association of Latino Arts and Cultures (NALAC) to undertake Writing Home, a collaboration with 15 undocumented artists and advocacy organizations that "seek[s] to shift the public, citizen imagination around undocumented individuals."[53] In 2021, he was the recipient of a $10,000 MACLA Cultura Power Fellowship, which supports "Latinx artists who are actively working to advance a more just and equitable society through their art making practices."[54] In 2022, the San José Museum of Art acquired Yosi con Abuela, a portrait of Reyes and his grandmother by artist Rafa Esparza, for its permanent collection. [55]

In summer 2024, Reyes traveled to México for the second time under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Advance Parole program for DACA recipients. There, he was recognized by the LXI Legislature of the Congress of the Free and Sovereign State of Puebla “for his contribution and commitment to the challenges faced by women [and] the promotion of cultural identity, global governance, migration, and international affairs.”[citation needed]

As a co-founder of La Maricolectiva,[56][57] a grassroots performance community, Reyes created a platform for queer, undocumented poets and creatives. He is also associated with DreamersAdrift.[58]

In solidarity with the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, Reyes educated the US Latino and undocumented communities on anti-blackness and systematic racism in Spanish via Univision and radio programs.[59]

Reyes has been recognized as one of "13 LGBT Latinos Changing the World" by The Advocate as well as a member of the OUT100 by Out Magazine.[60][61]

Mardonia Galeana

[edit]Mardonia Galeana, known as "Mama Doña",[62] was Reyes's grandmother, whom she raised from the age of 3.[63] Originally from the Mexican state of Guerrero, Galeana and Reyes immigrated to the United States in the early 1990's, relocating to the Tropicana neighborhood on the East Side of San Jose.[63] As an undocumented immigrant in the United States, Galeana worked many informal jobs to support her family, from recycling beer bottles and soda cans to selling home cooked meals in her apartment to her local immigrant community.[63][64]

During the COVID pandemic, Reyes became Galeana's primary caregiver.[65] On his private Instagram account Reyes started documenting his life with his grandmother, where Galeana became well-known to his thousands of followers.[65] Reyes has written several works inspired by his grandmother such as "Bottle Dreams", "Ofrenda de Palabra", and "Abuela Gets a Fever".[66][65]

Galeana was featured in several artistic works alongside her poet grandson. In 2021, Bay area and Latinx artist, Elizabeth Blancas created a mural about COVID prevention and recovery in the Mission District's Clarion Alley. The mural depicts Reyes' embracing Galeana while wearing masks. The mural features a quote, "Tú eres mi otro yo/You are my other me" from Chicano playwright Luis Valdez's 1973 poem, "Pensamiento Serpentino". The mural was commissioned by San Francisco's COVID Command Center and the Clarion Alley Mural Project.[67][68][69]

In 2021, artist rafa esparza, painted "Yosi con Abuelita".[70] In the painting, Yosi stands behind Galeana, who is wearing his cobija coat, an item created by Los Angeles fashion artist Brenda Equihua.[71] "Yosi con Abuelita" is a part of the San Jose Museum of Art's permanent collection.[70]

For KQED's series, "The Bay Area's Great Immigrant Food City", Reyes wrote about his early life with Galeana in the article, "My Abuela's East San Jose Kitchen Fed Dozens of Undocumented Workers Every Week".[72][73]

Bibliography

[edit]- [Anthologized in] Xavier, Emanuel. MARIPOSAS: A Modern Anthology of Queer Latino Poetry. Floricanto Press. 2008. Print.[74]

- Reyes, Yosimar. For Colored Boys Who Speak Softly, Self-Published, 2009. Print.[75]

- [Anthologized in] Pinate, Marc David. La Lunada: An Anthology. CreateSpace Independent Publishing. 2010. Print.[76]

- [Anthologized in] Del Castillo, Adelaida R, and Guido Gibran. Queer In Aztlan: Male Recollections of Consciousness and Coming Out, Cognella Academic Publishing, 2013. Print.[77]

- [Anthologized in] King, Nia. Queer and Trans Artists of Color: Stories of Some of Our Lives. CreateSpace Independent Publishing, 2014. Print.[78]

- [Anthologized in] HerrerayLozano, Lorenzo. Joto: An Anthology of Queer Xicano & Chicano Poetry. Korima Press. Forthcoming. Print.[79]

- [Anthologized in] R., D. C. A., & Güido, G. Fathers, fathering, and Fatherhood: Queer Chicano/Mexicano Desire and belonging. Palgrave Macmillan, 2021. Print. [80]

- [Anthologized in] Castillo, M.H. and Joseph, J. and Lin, E. Here to Stay: Poetry and Prose from the Undocumented Diaspora. Harper Collins, 2024. Print. [81]

- [Anthologized in] González, R. Latino Poetry: The Library of America Anthology (LOA #382). Penguin Random House, 2024. Print. [82]

- Prieto. By Yosimar Reyes. Dirs. Kat Evasco, Sarita Ocón. Galería de la Raza, San Francisco. 16–18 June 2016.[83]

References

[edit]- ^ "Queer Undocumented Poet Yosimar Reyes Doesn't Care About Impressing Racists". Vice. 2018-08-09. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- ^ a b For Colored Boys Who Speak Softly Archived September 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine by Yosimar Reyes (Evolutionary Productions, August 13, 2011)

- ^ Yessica Frias [1] “Guelaguetza” ‘’Student Event Finder’ June 2, 2013

- ^ "Documenting Joy: Shifting Narratives in Undocumented Storytelling with Yosimar Reyes". LGBT Center — Princeton University. Retrieved 2017-09-13.

- ^ San Francisco Public Library (2016-06-13), Yosimar Reyes at Radar Reading Series, retrieved 2017-12-07

- ^ "2017 Conversation Series : Program & Events : Park Avenue Armory". Park Avenue Armory. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ "Yosimar Reyes | Aspen Ideas Festival". Aspen Ideas Festival. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ "Dolores Huerta Lecture in conversation with Yosimar Reyes | Latin American and Latinx Studies Program". lals.sas.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- ^ "Yosimar Reyes". dacaseminar.fas.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- ^ "Amerikanistik: Events". www.amerikanistik.uni-saarland.de. Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- ^ MACLA (May 24, 2023). "Join us in welcoming MACLA's first ever Performing Artist in Residence (PAIR), Yosimar Reyes!". Retrieved May 24, 2023 – via Instagram.

- ^ "Instagram". www.instagram.com. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "News | City of San José". www.sanjoseca.gov. Retrieved 2024-01-18.

- ^ "Yosimar Reyes Appointed Santa Clara County Poet Laureate by Board of Supervisors for 2024-25". sccld.org. 2024-01-25. Retrieved 2024-01-26.

- ^ Holtzclaw, Barry (January 31, 2024). "New Poet Laureate: Yosimar Reyes". Metro Silicon Valley. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ "Our Team". www.defineamerican.com. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ^ "Galería de la Raza: Rentals". galeriadelaraza.org. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ^ Webostvalire (2011-05-17), Yosimar Reyes en entrevista para Rutas Creativas, retrieved 2016-04-01

- ^ "The Immigration Ruling Is Another Hit Against Queer Latinos". 2016-06-27. Retrieved 2016-06-27.

- ^ "A Barrio dreamer's poetry: S.J. man's verse has caught attention, but can it pay bills?". San Jose Mercury News. April 21, 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ a b c Yosimar Reyes entrevista para Rutas Creativas (YouTube, May 17, 2011)

- ^ "Rodriguez: Poor, brown and gay: Poetry makes Reyes' day, can it pay?". The Mercury News. 2009-04-16. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ Marquez, Stacy (2018-03-21). "UndocuQueer artists tackle media representation and empowerment". The Daily Aztec. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ Savard, Molly (2018-07-10). "Finding Life's Poetry with Yosimar Reyes". Shondaland. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- ^ "2nd Verse, the rebirth of poetry". 2ndversefilm.com. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- ^ "Rodriguez: Poor, brown and gay: Poetry makes Reyes' day, can it pay?". The Mercury News. 2009-04-16. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- ^ Del Castillo, Adelaida R; Güido, Gibrán (2014-01-01). Queer in Aztlán: Chicano male recollections of consciousness and coming out. [San Diego, CA]: Cognella Academic. ISBN 9781621318057. OCLC 875186264.

- ^ "Somewhere We Are Human". HarperCollins. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

- ^ "Yosimar Reyes Bio". Things I'll Never Say. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ^ O'Donnell, B.R.J. "What Mentorship Can Mean to Undocumented Immigrants". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ Herreria, Carla (2017-09-03). "This Spoken Word Poem Is A Beautiful Love Letter To 'Undocumented People'". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ Reyes, Yosimar (2016-09-02). "Goodwill Trucks". Yosimar Reyes. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ "10 Up and Coming Latinx Poets You Need to Know". Remezcla. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ Nunez, Yazmin (2018-08-09). "Queer Undocumented Poet Yosimar Reyes Doesn't Care About Impressing Racists". Vice. Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- ^ Reyes, Yosimar. "Undocumented People Are MUCH More Than the Stories You're Told About Them". Teen Vogue. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ Reyes, Yosimar. "In a "Nation of Immigrants," Who Chooses Who Belongs?". Teen Vogue. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- ^ "Galería de la Raza | globalgalleryguide.saatchigallery.com". www.saatchigallery.com. 2016-06-15. Retrieved 2016-06-18.

- ^ "INTO: A Digital Magazine for The Modern Queer World". www.intomore.com. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- ^ "Prieto". Brava for Women in the Arts. Retrieved 2022-09-30.

- ^ "Prieto at MACLA - MACLA". Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- ^ "Chicago Shakespeare Theater: Prieto". www.chicagoshakes.com. 7 November 2023. Retrieved 2024-01-18.

- ^ "Undocupoets". Siblingrivalrypress. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- ^ "Yosimar Reyes | Lambda Literary". Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- ^ Paisa, retrieved 2020-06-16

- ^ "Yosimar Reyes (@yosirey) • Instagram photos and videos". www.instagram.com. Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- ^ "The Book Club Expanding the Latinx Literary Canon — One Conversation at a Time". KQED. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- ^ "Galería de la Raza: Exhibition: Studio 24 - Migrating Sexuality: Unspoken Stories of Land, Body and Sex". www.galeriadelaraza.org. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ^ Saldivar, Steve (2017-03-05). "At Boyle Heights arts show 'We Never Needed Papers to Thrive,' immigrants are the focus — and the stars". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ "Flipping the Narrative of the Undocumented from Pain to Joy". KQED Arts. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- ^ "Yosimar Reyes - #XMAP: In Plain Sight". Yosimar Reyes - #XMAP: In Plain Sight. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- ^ Crawford, Iris M. (2021-02-01). "Creatives in Place asks: What do artists need to survive and thrive in the Bay Area?". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2021-02-02.

- ^ "Yosimar Reyes". Creatives In Place. Retrieved 2021-02-02.

- ^ Program, Grants (2020-11-18). "Yosimar Reyes". NALAC. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Artist Fellowship Program 2021 - MACLA". Retrieved 2021-03-15.

- ^ "Evergreen: Art from the Collection". San José Museum of Art. 22 July 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- ^ "La Maricolectiva | Student Of Color Conference 2010". Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ^ "Yosimar Reyes". dacaseminar.fas.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- ^ ""The Ashes" by Yosimar Reyes | DreamersAdrift". dreamersadrift.com. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ^ Univision. ""Muchas veces se enfocan en lo negativo": escritor sobre el papel de los medios de comunicación en las protestas". Univision (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- ^ "13 LGBT Latinos Changing the World". www.advocate.com. 2015-09-28. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- ^ "OUT100 2017". 2017-11-08. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ "Mural: Photo Essay". El Tecolote. 2021-03-12. Retrieved 2024-11-11.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez, Joe (2009-04-16). "Rodriguez: Poor, brown and gay: Poetry makes Reyes' day, can it pay?". The Mercury News. Retrieved 2024-11-11.

- ^ "A Look at the Bay Area's Perseverance in 2021 Through Photos". KQED. 2021-12-21. Retrieved 2024-11-11.

- ^ a b c Rojas, Frank (2024-04-03). "'Carefluencers' Are Helping Older Loved Ones, and Posting About It". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2024-04-04. Retrieved 2024-11-11.

- ^ Rodriguez, Joe (2009-04-16). "Rodriguez: Poor, brown and gay: Poetry makes Reyes' day, can it pay?". The Mercury News. Retrieved 2024-11-11.

- ^ "Mural: Photo Essay". El Tecolote. 2021-03-12. Retrieved 2024-11-11.

- ^ Montes, Daniel (2021-05-03). "S.F. mural celebrates Latino community, spotlight impacts of COVID pandemic". Bay City News. Retrieved 2024-11-11.

- ^ "City commissions new mural celebrating the strong family and community bonds helping SF's Latinx community heal". 2021-04-29. Retrieved 2024-11-11.

- ^ a b "Evergreen: Art from the Collection | San José Museum of Art". San Jose Museum of Art. 2022-07-22. Retrieved 2024-11-11.

- ^ James, Julissa (2021-05-26). "The L.A. designer who remade the cobija into luxury fashion". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2024-11-11.

- ^ "A Look at the Bay Area's Perseverance in 2021 Through Photos". KQED. 2021-12-21. Retrieved 2024-11-11.

- ^ Reyes, Yosimar (2021-10-21). "My Abuela's East San Jose Kitchen Fed Dozens of Undocumented Workers Every Week | KQED". KQED. Retrieved 2024-11-11.

- ^ "Mariposas". www.floricantopress.com. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ^ "For Colored Boys Who Speak Softly". Goodreads. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ^ Depository, Book. "La Lunada : Marc David Pinate : 9781451577310". www.bookdepository.com. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ^ "Queer in Aztlán". Cognella. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ^ King, Nia (2014-06-05). Mikalson, Terra; Glennon-Zukoff, Jessica (eds.). Queer and Trans Artists of Color: Stories of Some of Our Lives. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 9781492215646.

- ^ "Amorcito Maricon Author - Kórima Press". korimapress.com. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ^ Castillo, Adelaida R. Del; Güido, Gibrán, eds. (2021). Fathers, Fathering, and Fatherhood: Queer Chicano/Mexicano Desire and Belonging. Palgrave Studies in Literary Anthropology. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-030-60876-7.

- ^ https://www.harpercollins.com/products/here-to-stay-marcelo-hernandez-castillojanine-josephesther-lin?variant=41517710737442.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/761114/latino-poetry-the-library-of-america-anthology-loa-382-by-rigoberto-gonzalez-editor/.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ ""Prieto", Autobiographical Solo Show by Yosimar Reyes". SF Weekly. Retrieved 2016-06-20.