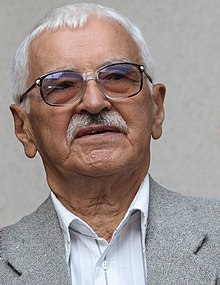

Yevhen Sverstiuk

Yevhen Oleksandrovych Sverstiuk (Ukrainian: Євге́н Олекса́ндрович Сверстю́к; 13 December 1927 - 1 December 2014) was a Ukrainian literary critic, essayist, poet, think tank, philosopher, participant of the sixtiers movement, and political prisoner of the Soviet regime.[1] Sverstiuk studied the work of Nikolai Gogol, Taras Shevchenko, and Ivan Franko. He was the founder and, since 1989 a permanent editor of the Orthodox newspaper Nasha Vira, president of the Ukrainian PEN Club.[2] Doctor of Philosophy. Author of one of the most important texts of Ukrainian self-publishing About the process of Pogruzhalskyi, head of Ukrainian Association of Independent Creative Intelligentsia.

Early life and education

[edit]Yevhen Sverstiuk was born on 13 December 1927 in the village of Siltse, Horokhiv County, Volyn Voivodeship, Republic of Poland, now Horokhiv Raion, Volyn Oblast, Ukraine.[3] His parents were peasants.[3] Sverstiuk studied at the Lviv State University, Department of Logic Psychology of the Faculty of Philology (1947-1952). Later, he was a graduate student at the Research Institute of Psychology of the Ministry of Education of Ukraine (1953-1956).

Career

[edit]In 1952, Sverstiuk worked as a Ukrainian language teacher in Pochaiv in the village of Bohdanivka of the Pidvolochy district (1953). He was a teacher of Ukrainian literature at the Poltava Pedagogical University (1956-1959) and a senior researcher at the Scientific Research Institute of Psychology (1959-1960).

From 1961 to 1962, Sverstiuk was the head of the prose department of the magazine Vitchyzna. Then, from 1962 to 1965, he was a senior researcher in the department of psychological education at the Research Institute of Psychology (1962-1965). From 1962 to 1972, Sverstiuk was the secretary of the Ukrainian Botanical Journal (1965-1972).[3]

In 1965, Sverstiuk got an appointment to defend his thesis for the degree of Candidate of Pedagogical Sciences at Odesa University. However, the defense did not take place.

In 1959, 1960, 1961, and 1965 Sverstiuk was fired from his job for political reasons for speaking out against the discrimination against Ukrainian culture and in 1972 for a speech at the funeral of Dmytro Zerov. Sverstiuk was persecuted for years for participating in Samvydav and protests against arrests and illegal trials.

In January 1972, Sverstiuk was arrested, and in March 1973, he was sentenced under Article 62 Part I of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR for the production and distribution of "self-publishing" documents to seven years in the camps.[2] He served in the Perm region and at the end, he received 15 days in solitary confinement, where he sat with criminal prisoners, avoided the "programmed" conflict with them by the administration of the "zone".[2] They gave him an icon as a farewell gift and years of exile.

Since February 1979, he worked as a carpenter on a geological expedition in Buryatia.[4] From October 1983 to 1988, Sverstiuk worked as a carpenter at the Kyiv industrial sewing factory No. 2.[4]

In the summer of 1987, along with Serhii Naboka, chairman of the council, Oles Shevchenko, Olga Heiko-Matusevich, Vitaly Shevchenko, Mykola Matusevich, and others, Sverstiuk created the Ukrainian Cultural Club (UCC).[5] In the summer of 1988, together with comrades from the Ukrainian Communist Party, Sverstiuk honored the 1000th anniversary of the Baptism of Rus-Ukraine near the monument of St. Volodymyr.

After the declaration of Ukraine's independence, Sverstiuk was an active ideologist of the de-Sovietization of the country. His publications devoted to overcoming the Soviet legacy in spiritual life are widely known.

He was one of the participants of the "First of December" initiative group - an association of Ukrainian intellectuals and public figures created in 2011.[6] In its composition, he was one of the authors of the National Act of Freedom - a social contract proposed to the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, which was published on 14 February 2014 and was intended to find ways out of the political crisis.[7]

Yevhen Sverstiuk died on 1 December 2014, twelve days before his 87th birthday. He was buried on 4 December 2014 at the Baikove cemetery (plot No. 33).[8] The burial ceremony took place in the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC), and the Teacher's House in Kyiv.

Writings

[edit]Sverstiuk is an author of books, numerous articles on literary studies, psychology, and religious studies; poems, as well as translations from German, English, and Russian into Ukrainian. Some of Sverstyuk's literary and critical essays appeared (mainly in the first half of the 1960s) in the magazines "Vitchyzna," "Dnipro," "Zhovten," "Duklya" (an essay about Mykola Zerov), the newspaper "Literature Ukraine ";[1] others (from the end of the 1960s) in "Samvydav" (Kotlyarevsky laughs, The Last Tear - about Taras Shevchenko, Vasyl Symonenko - an idea, Traces of tales about Ivan's youth, etc.), reprinted abroad (mainly in the collection "Wide Sea of Ukraine", 1972, "Panorama of the newest literature in the Ukrainian SSR," 1974).[5] The essay The Cathedral in the Scaffolding (1970) was published as a separate book (in "Samvydav") about the novel The Cathedral by Oles Honchar.

Selected works

[edit]- Prodigal sons of Ukraine. Compiled by Taras Marusyk. - Kyiv: "Knowledge" of Ukraine, 1993. - 256 p. Cover and illustrations by Opanas Zalivakha. A collection of essays, literary and critical articles, and the author's speeches dedicated to the revival of spirituality and moral and ethical problems. - ("Kobza"; 1–2; 3–4. Series 6. Writers of Ukraine and the Diaspora).[9]

- On the feast of hope. - Kyiv: Our faith, 1999. 784 pages.

- On the waves of "Freedom." Short essays. - Lutsk: VMA "Teren", 2004.

- Not peace, but a sword. Essays. - Lutsk: VMA "Teren", 2009.

- The truth is wormwood. - Kyiv, Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, 2009.

- Shevchenko beyond time. Essays. / Compiled by Oleksiy Sinchenko. - Lutsk: VMA "Teren" - Kyiv: Publishing House "Kyiv-Mohyla Academy," 2011. - 277 p.

- Gogol and the Ukrainian night / Compiled by Oleksiy Sinchenko. - Kyiv: Clio, 2013.[10]

- Bright voices of life. - Kyiv: Clio, 2015.[11]

Awards and honors

[edit]Sverstiuk was awarded the Order of Liberty "...for outstanding services in asserting the sovereignty and independence of Ukraine, courage, and dedication in defending human rights and freedoms, fruitful literary and journalistic activity and on the occasion of Freedom Day..." according to the Decree of the President of Ukraine "On awarding Yevhen Sverstiuk with the Order of Freedom” dated 25 November 2008 No. 1075/2008.[12]

Other awards include Shevchenko National Prize (1995) for the book Prodigal Sons of Ukraine,[6] Light of Justice Award (2010) and Unesco Corneliu Coposu Prize (2000).[13]

Commemoration

[edit]In 2015, streets in Kyiv and Brovary were renamed in honor of Yevhen Sverstiuk.[14] Since May 2016, Yevgen Sverstyuk Street has also appeared in Poltava. In 2016, Evgen Sverstiuk Street appeared in the city of Kropyvnytskyi. A street in Lutsk is named after Yevhen Sverstiuk, and a commemorative plaque is dedicated to him.

On 13 December 2018, the 90th anniversary of the birth of Yevhen Sverstyuk (1928-2014) was celebrated at the state level in Ukraine.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Євген Сверстюк — християнський голос секулярної доби". Патріярхат (in Ukrainian). 2018-03-20. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ a b c "Інтерв'ю з Євгеном Сверстюком — Архів ОУН". ounuis.info (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ a b c Штогрін, Ірина (3 December 2020). "Євген Сверстюк. День пам'яті. Претендентам на місце в українській еліті є на кого рівнятися". Радіо Свобода (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ a b "Сверстюк Євген Олександрович". Львівський національний університет імені Івана Франка (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ a b "СВЕРСТЮК ЄВГЕН ОЛЕКСАНДРОВИЧ". resource.history.org.ua. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ a b "Євген Сверстюк: "І настрій народу був такий, що йому потрібна була ця легенда"". Історична правда. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ "Група "Першого грудня" пропонує сторонам підписати Національний акт свободи". Українська правда (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ "Дисидента Сверстюка поховають на Байковому кладовищі у четвер". espreso.tv (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ Sversti︠u︡k, I︠E︡vhen; Сверстюк, Євген (1993). Bludni syny Ukraïny. Kyïv: T-vo "Znanni︠a︡" Ukraïny. ISBN 5-7770-0822-4. OCLC 30629506.

- ^ Sversti︠u︡k, I︠E︡vhen; Сверстюк, Євген (2013). Hoholʹ i ukraïnsʹka nich : Eseï. Oleksiĭ Sinchenko, Олексій Сінченко. Kyïv. ISBN 978-617-7023-05-9. OCLC 847140006.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Sversti︠u︡k, I︠E︡vhen; Сверстюк, Євген (2015). Svitli holosy z︠h︡ytti︠a︡. Kyïv. ISBN 978-617-7023-21-9. OCLC 902633796.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Про нагородження Є. Сверстюка орденом Свободи". Офіційний вебпортал парламенту України (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ Sinchenko, Oleksii Stus, Dmytro Finberg, Leonid (2021-03-16). Ukrainian Dissidents: An Anthology of Texts. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 386. ISBN 978-3-8382-1551-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Київська міська Рада, рішення" (PDF). Хрещатик. 2015-10-28. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ "Про відзначення пам'ятних дат і ювілеїв у 2018 році". Офіційний вебпортал парламенту України (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-09-14.