Yangzhou massacre

| Yangzhou massacre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

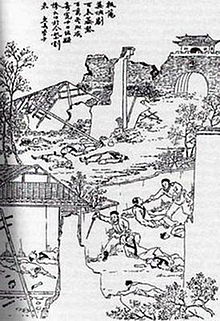

An artist conception of the massacre from the late Qing dynasty | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 揚州十日 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 扬州十日 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Ten Days of Yangzhou | ||||||

| |||||||

The Yangzhou massacre in May, 1645 in Yangzhou, Qing dynasty China, refers to the mass killing of people in Yangzhou commanded by the Manchu general Dodo and carried out by Qing forces.

The massacre is described in a contemporary account, A Record of Ten Days in Yangzhou, by Wang Xiuchu. Due to the title of the account, the events are often referred to as a ten-day massacre, but the diary shows that the slaughter was over by the sixth day, when burial of bodies commenced.[1] According to Wang, the number of victims exceeded 800,000, that number is now disproven and considered by modern historians and researchers to be an extreme exaggeration.[2][3][4][5] The major defending commanders of Ming, such as Shi Kefa, were also executed by Qing forces after they refused to submit to Qing authority.

The alleged reasons for the massacre were:

- To punish the residents because of resistance efforts led by the Ming official Shi Kefa.

- To warn the rest of the population in Jiangnan of the consequences of participating in military activities and resisting the Qing invaders.

Wang Xiuchu's account has appeared in a number of English translations, including by Backhouse and Bland,[6] Lucien Mao,[7] and Lynn A. Struve. Following are excerpts from the account in the translation by Struve.[8]

Several dozen people were herded like sheep or goats. Any who lagged were flogged or killed outright. The women were bound together at the necks with a heavy rope—strung one to another like pearls. Stumbling with each step, they were covered with mud. Babies lay everywhere on the ground. The organs of those trampled like turf under horses' hooves or people's feet were smeared in the dirt, and the crying of those still alive filled the whole outdoors. Every gutter or pond we passed was stacked with corpses, pillowing each others arms and legs. Their blood had flowed into the water, and the combination of green and red was producing a spectrum of colours. The canals, too, had been filled to level with dead bodies.

Then fires started everywhere, and the thatched houses...caught fire and were soon engulfed in flames...Those who had hidden themselves beneath the houses were forced to rush out from the heat of the fire, and as soon as they came out, in nine cases out of ten, they were put to death on the spot. On the other hand, those who had stayed in the houses—were burned to death within the closely shuttered doors and no one could tell how many had died from the pile of charred bones that remained afterwards.

Books written about the massacres in Yangzhou, Jiading and Jiangyin were later republished by anti-Qing authors to win support in the lead up to the Taiping Rebellion and Xinhai Revolution.[9][10]

Qing soldiers ransomed women captured from Yangzhou back to their original husbands and fathers in Nanjing after Nanjing peacefully surrendered, corralling the women into the city and whipping them hard, with their hair containing a tag showing the price of the ransom.[11]

There was a Hui Muslim community in Yangzhou during the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties with historic mosques like Crane Mosque and the tomb of Sayyid Puhaddin.[12][13][14]

Accounts of atrocities like the Yangzhou massacre during the transition from the Ming to Qing were used by revolutionaries in the anti-Qing Xinhai revolution to fuel massacres against Manchus.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "揚州十日記 - 维基文库,自由的图书馆". zh.wikisource.org. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ^ Antonia Finnane (2004). Speaking of Yangzhou: A Chinese City, 1550-1850. Harvard University Asia Center. p. 453. ISBN 978-0674013926.

- ^ 谢国桢,《南明史略》,第72—73页

- ^ 张德芳《〈扬州十日记〉辨误》,中华文史论丛,第368-370页

- ^ Struve (1993) (note at p. 269), following a 1964 article by Zhang Defang, notes that the entire city's population at the time was not likely to be more than 300,000, and that of the entire Yangzhou Prefecture, 800,000.

- ^ E.Backhouse and J.O.P. Bland, 'The Sack of Yang Chou-fu.' In Annals and Memoirs of the Court of Peking. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914.

- ^ "A Memoir of the Ten Days' Massacre at Yangchow." Trans. Lucien Mao. Tien-hsia Monthly 4, no. 5 (May 1937): 515-37.

- ^ Struve, Lynn A., Voices from the Ming-Qing Cataclysm: China in Tigers' Jaws (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), pp.32-48

- ^ 朱子素, 嘉定屠城紀略

- ^ 韓菼, 江陰城守紀

- ^ Yao, Wenxi (1993). Struve, Lynn A. (ed.). Voices from the Ming-Qing Cataclysm: China in Tigers' Jaws (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Yale University Press. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0300075537.

- ^ "Puhading Yuan in Yangzhou - Attraction | Frommer's".

- ^ "Xianhe Mosque in Yangzhou of Jiangsu, Muslim Mosque in Yangzhou".

- ^ "Puhading Cemetery, Yangzhou".

Literature

[edit]- Struve, Lynn A., Voices from the Ming-Qing Cataclysm: China in Tigers' Jaws, Publisher:Yale University Press, 1998, See pp. 32–48 for the translation of Wang Xiuchu's account.

- Finnane, Antonia, Speaking of Yangzhou: A Chinese City, 1550-1850, Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2004. See especially Chapter 4, "Yangzhou's Ten Days."

- Wei, Minghua 伟明铧, 1994. “Shuo Ýangzhou shiri’”说扬州十日, in Wei Minghua, Yangzhou tanpian 扬州谈片 Beijing: Sanlian shudian.

- Zarrow, Peter, 2004. “Historical Trauma: Anti-Manchuism and Memories of Atrocity in Late Qing China,” History and Memory, Vol. 16, No. 2, Special Issue: Traumatic Memory in Chinese History.

- The Litigation Master and the Monkey King, Liu, Ken. In The Paper Menagerie and other stories. Publisher:Saga Press, 2016, ISBN 978-1-4814-2437-0. pages 363–388.