A Wrinkle in Time

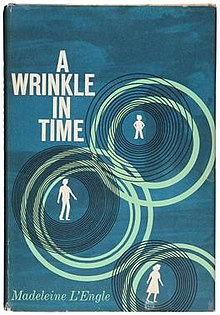

First-edition dust jacket | |

| Author | Madeleine L'Engle |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Ellen Raskin (1960s editions) |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Young adult, science fantasy |

| Publisher | Ariel Books |

Publication date | January 1, 1962 |

| Publication place | United States |

| OCLC | 22421788 |

| LC Class | PZ7.L5385 Wr 1962[1] |

| Followed by | A Wind in the Door |

A Wrinkle in Time is a young adult science fantasy novel written by American author Madeleine L'Engle. First published in 1962,[2] the book won the Newbery Medal, the Sequoyah Book Award and the Lewis Carroll Shelf Award, and was runner-up for the Hans Christian Andersen Award.[3][a] The main characters – Meg Murry, Charles Wallace Murry, and Calvin O'Keefe – embark on a journey through space and time, from galaxy to galaxy, as they endeavor to rescue the Murrys' father and fight The Black Thing that has intruded into several worlds.

The novel offers a glimpse into the war between light and darkness, and good and evil, as the young characters mature into adolescents on their journey,[4] and wrestles with questions of spirituality and purpose, as the characters are often thrown into conflicts of love, divinity, and goodness.[4] It is the first book in L'Engle's Time Quintet, which follows the Murry family and O'Keefe.

L'Engle modeled the Murry family on her own. B. E. Cullinan noted that L'Engle created characters who "share common joy with a mixed fantasy and science fiction setting".[5] The novel's scientific and religious undertones are therefore highly reflective of the life of L'Engle.[6]

The book has inspired a 2003 television film directed by John Kent Harrison, and a 2018 theatrical film directed by Ava DuVernay, both produced by The Walt Disney Company.

Background

[edit]Raised in the Upper East Side of Manhattan, author Madeleine L'Engle began writing at a young age.[7] After graduating from boarding school in Switzerland, she attended Smith College, where she earned a degree in English.[8] In addition to writing, L'Engle also gained experience as an actor and playwright.[7] At age forty, she nearly abandoned her career as a novelist, but continued to write after her publication of Meet the Austins.[7]

L'Engle wrote A Wrinkle in Time between 1959 and 1960.[9] In her memoir, L'Engle explains that the book was conceived "during a time of transition".[10] After years of living in rural Goshen, Connecticut where they ran a general store, L'Engle's family, the Franklins, moved back to New York City, first taking a ten-week camping trip across the country. L'Engle writes that "we drove through a world of deserts and buttes and leafless mountains, wholly new and alien to me. And suddenly into my mind came the names, Mrs Whatsit. Mrs Who. Mrs Which."[10] This was in the spring of 1959. When asked for more information in an interview with Horn Book magazine in 1983, L'Engle responded

I cannot possibly tell you how I came to write it. It was simply a book I had to write. I had no choice. It was only after it was written that I realized what some of it meant.[11]

L'Engle has also described the novel as her "psalm of praise to life, [her] stand for life against death."[11]

Additionally, L'Engle drew upon her interest in science. The novel includes references to Einstein's theory of relativity and Planck's quantum theory.[7]

A Wrinkle in Time is the first novel in the Time Quintet, a series of five young-adult novels by L'Engle.[12] Later books include A Wind in the Door, A Swiftly Tilting Planet, Many Waters, and An Acceptable Time.[12] The series follows the adventures of Meg Murry, her youngest brother Charles Wallace Murry, their friend Calvin O'Keefe, and her twin siblings Sandy and Dennys Murry.[12] Throughout the series, family members band together to travel through time as they attempt to save the world from the grasps of evil.[12]

Publication history

[edit]Upon completion in 1960, the novel was rejected by at least 26 publishers, because it was, in L'Engle's words, "too different," and "because it deals overtly with the problem of evil, and it was really difficult for children, and was it a children's or an adults' book, anyhow?"[2][10]

In "A special message from Madeleine L'Engle", L'Engle offers another possible reason for the rejections: "A Wrinkle in Time had a female protagonist in a science fiction book",[13] which at the time was rare.

After trying "forty-odd" publishers (L'Engle later said "twenty-six rejections"), L'Engle's agent returned the manuscript to her. Then at Christmas, L'Engle threw a tea party for her mother. One of the guests happened to know J.C. Farrar of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, and he insisted that L'Engle should meet with him.[13] Although the publisher did not, at the time, publish a line of children's books, Farrar met L'Engle, liked the novel, and ultimately published it under the Ariel imprint.[13]

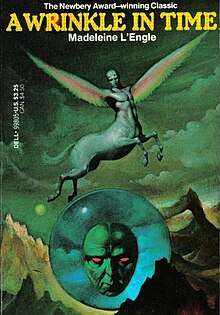

In 1963, the book won the Newbery Medal, an annual award given by the Association for Library Service to Children, a division of the American Library Association, to the author of the most distinguished contribution to American children's literature. The book has been continuously in print since its first publication. The hardback edition is still published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux. The original blue dust jacket by Ellen Raskin was replaced with new art by Leo and Diane Dillon, with the publication of A Swiftly Tilting Planet in 1978. The book has also been published in a 25th anniversary collectors' edition (limited to 500 signed and numbered copies), at least two book club editions (one hardback, one Scholastic Book Services paperback), as a trade paperback under the Dell Yearling imprint, and as a mass market paperback under the Dell Laurel-Leaf imprint. The cover art on the paperback editions has changed several times since its first publication.[14]

The book was reissued by Square Fish in trade and mass market paperback formats in May 2007, along with the rest of the Time Quintet. This new edition includes a previously unpublished interview with L'Engle as well as a transcription of her Newbery Medal acceptance speech.[15]

Plot summary

[edit]One night, thirteen-year-old Meg Murry meets an eccentric new neighbor, Mrs. Whatsit, who refers to something called a tesseract. Meg later finds out it is a scientific concept her father was working on before his mysterious disappearance. The following day, Meg, her child genius brother Charles Wallace, and fellow schoolmate Calvin visit Mrs. Whatsit's home, where the equally strange Mrs. Who and the voice of the unseen Mrs. Which promise to help Meg find and rescue her father.

Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which turn out to be supernatural beings who teleport Meg, Charles Wallace, and Calvin O'Keefe through the universe by means of a tesseract, a fifth-dimensional phenomenon explained as folding the fabric of space and time; this form of travel is called tessering. Their first stop is the planet Uriel, a world inhabited by centaur-like beings who live in a state of light and love, fighting against the approaching darkness. There, the Mrs. Ws demonstrate to the children how the universe is under attack from an evil being that appears particularly clearly on Uriel as an overwhelming dark cloud, called The Black Thing. They then take the children to Orion's Belt to visit the Happy Medium, a far-seeing person with a crystal ball through which they are shown that Earth is partially covered by the darkness, although great religious figures, philosophers, scientists, and artists, have been fighting against it. Mrs. Whatsit is revealed to be a former star, who exploded in an act of self-sacrifice to fight the darkness.

The three Mrs. Ws tesser the children to the edge of the inhabited part of a dark planet named Camazotz, which has succumbed to The Black Thing, and where the Mrs. Ws cannot themselves enter. Meg's and Charles Wallace's father, Alex Murry, is imprisoned in a nearby city because he refused to yield to the group mind that causes inhabitants to behave in a mechanical way. When they reach the CENTRAL Central Intelligence building, Charles Wallace deliberately allows himself to be hypnotized, in order to find where their father is kept. Controlled by the group mind, Charles Wallace takes Meg and Calvin to the place where Meg's father is being held prisoner. He then takes them to IT, the disembodied brain with powerful telepathic abilities that controls the planet. Using special powers from Mrs. Who's glasses, Meg is able to reach her father, who tessers Calvin, Meg, and himself to the adjacent planet Ixchel, before IT can control them all. Charles Wallace is left behind, still under the influence of IT, Meg is paralyzed from contact with The Black Thing during the trip, and Dr. Murry suffers broken ribs. The inhabitants of Ixchel are beast-like, with featureless faces, tentacles, and four arms. Despite their frightening appearance, they prove to be both wise and gentle; one cures Meg's paralysis, prompting Meg to nickname it "Aunt Beast".

The trio of Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which arrive on Ixchel, before Alex Murry has recovered, and assign the rescue of Charles Wallace to Meg alone. Arriving at the building where IT resides, she finds Charles Wallace still under IT's control. Inspired by hints from the Mrs. Ws, Meg focuses all her love on Charles Wallace and is able to free him from IT, at which point Mrs. Which remotely tessers Meg and Charles Wallace off Camazotz.

They all then tesser back to Earth, to the edge of the forest near the Murry home, and back to the moment in time just after the Mrs. Ws and the children originally left Earth. Then the Mrs. Ws vanish.[b]

Characters

[edit]Main characters

[edit]Margaret "Meg" Murry

[edit]Meg is the oldest child of scientists Alex and Kate Murry, about thirteen years old. Introduced on the first page of the book, she is the story's main protagonist. One of Kate Murry's "abnormal" children, she seems to have a temper and a difficult time focusing in school. She was portrayed by Katie Stuart in the 2003 film and by Storm Reid in the 2018 film.

Charles Wallace Murry

[edit]Charles Wallace is the youngest Murry child, at six years old. Charles Wallace speaks only to his family, but can empathically or telepathically read certain people's thoughts and feelings. He was portrayed by David Dorfman in the 2003 film and by Deric McCabe in the 2018 film.

Calvin O'Keefe

[edit]Calvin is the third oldest of Paddy and Branwen O'Keefe's eleven children: a tall, thin, red-haired 14-year-old high school junior. He was portrayed by Gregory Smith in the 2003 film, and by Levi Miller in the 2018 film.

Supernatural characters

[edit]

Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which

[edit]The Mrs. Ws are immortal beings who can travel across large stretches of both space and time by dematerializing and rematerializing ("tessering"). They are all capable of shapeshifting, but appear as elderly women for almost all of the story.

Mrs. Whatsit is the youngest of the Mrs. Ws (despite being 2,379,152,497 years, 8 months, and 3 days old), and has the most interaction with the children. In a past life she was a star, and when reminded, still grieves for the loss of life on her former planets, when the star she was, died.

Mrs. Who communicates by quoting (and translating) literary sayings in Latin, Spanish, Italian, German, French, Portuguese, and Greek. When the Mrs. Ws leave the group on Camazotz, for no immediately obvious reason, Mrs. Who loans Meg her glasses.

Mrs. Which is the leader of the three women, the oldest of them, and the most skilled at tessering. However, she has nearly forgotten what a body is like, so has difficulty maintaining a solid form, and because of this does make a mistake while tessering to Camazotz. She is usually business-like and unemotional towards the children.

IT

[edit]

"IT" is the telepathic brain that controls the planet of Camazotz. IT appears as a giant-sized, disembodied human brain, housed in a transparent jar. While IT usually speaks through one of its pawns (such as the Man with Red Eyes) IT can speak directly to people via telepathy. IT is either an avatar or a servant of The Black Thing.

The Black Thing

[edit]The Black Thing, a formless, shadowy being, is the source of all evil in the universe.

Secondary characters

[edit]Dr. Alexander "Alex" Murry

[edit]Alex Murry, the father of the Murry children, is a physicist who is researching tesseracts and their relation to the mysteries of the space / time continuum. At the start of the novel, he has been missing for some time.

Dr. Katherine "Kate" Murry

[edit]Katherine Murry, the mother of the Murry children, is a microbiologist. She is considered beautiful by the Murry children and others, having "flaming red hair", creamy skin, and violet eyes with long dark lashes.

Sandy and Dennys Murry

[edit]Sandy (named after his father Alexander, also goes by "Xan") and his twin brother Dennys ("Den") are the middle children in the Murry family, older than Charles Wallace but younger than Meg. They are 10 years old and are depicted as inseparable at the time of this book. They are the only "normal" and socially accepted children in the Murry family.

Mrs. Buncombe

[edit]Mrs. Buncombe is the wife of the constable in Meg's hometown.

Mr. Jenkins

[edit]Mr. Jenkins is Meg's high-school principal who implies that her family is in denial about Dr. Alex Murry's true whereabouts.

Supporting alien characters

[edit]Happy Medium

[edit]The Happy Medium is human in appearance, but of uncertain gender. She uses her powers and a crystal ball to look at distant places and people. She prefers to look for happy events and her customary demeanor is jolly, but becomes sad upon viewing sad events. She lives in a cavern on a planet in Orion's Belt.

Aunt Beast

[edit]Aunt Beast is a nurturing creature who cares after Meg on the planet Ixchel, the next planet out from Camazotz, nursing Meg back towards wholeness after exposure to The Black Thing. "Aunt Beast" is a name created by Meg that the character accepts; her actual name, if any, is not given. She is a human-sized, furry, four-armed, eyeless gray creature with telepathic abilities. Instead of fingers she has numerous long, waving tentacles.

Analysis

[edit]Religion

[edit]The novel is highly spiritualized, with notable influences of divine intervention and prominent undertones of religious messages.[16] According to James Beasley Simpson, the overwhelming love and desire for light within the novel is directly representative of a Christian love for God and Jesus Christ.[16] Furthermore, the children encounter spiritual intervention, signaling God's presence in the ordinary, as well as the extendibility of God's power and love.[4] Madeleine L'Engle's fantasy works are in part highly expressive of her Christian viewpoint in a manner somewhat similar to that of Christian fantasy writer C.S. Lewis.[c] L'Engle's liberal Christianity has been the target of criticism from conservative Christians, especially with respect to certain elements of A Wrinkle in Time.[18]

L'Engle utilizes numerous religious references and allusions in the naming of locations within the novel. Camazotz is the name of a Mayan bat god, one of L'Engle's many mythological allusions in her nomenclature.[19] The name Ixchel refers to a Mayan jaguar goddess of medicine.[19] Uriel is a planet with extremely tall mountains, an allusion to the Archangel Uriel. It is inhabited by creatures that resemble winged centaurs. It is "the third planet of the star Malak (meaning 'angel' in Hebrew) in the spiral galaxy Messier 101", which would place it at roughly 21 million light-years from Earth. The site of Mrs Whatsit's temporary transformation into one of these winged creatures, it is the place where "the guardian angels show the questers a vision of the universe that is obscured on earth."[18](p 26) The three women are described as ancient beings who act as guardian angels.[18](p 26)

The theme of picturing the fight of good against evil as a battle of light and darkness is a recurring one. Its manner is reminiscent of the prologue to the Gospel of John, which is quoted within the book.[5] When the Mrs Ws reveal their secret roles in the cosmic fight against darkness, they ask the children to name some figures on Earth, a partially dark planet, who fight the darkness. They name Jesus and, later in the discussion, the Buddha is named as well.

Nevertheless, religious journalist Sarah Pulliam Bailey doubts whether the novel contains religious undertones.[6] Bailey explains that many readers somehow believe the novel promotes witchcraft, as opposed to alluding to Christian spirituality.[6] Bailey states that conservative Christians take offense, due to the novel's potential relativistic qualities, suggesting the various interpretations of religious allusions signals anti-Christian sentiments.[6] However, in her personal journal referencing A Wrinkle in Time, L'Engle confirms the religious content within the novel: "If I've ever written a book that says what I feel about God and the universe, this is it."[6]

Conformity

[edit]Themes of conformity and yielding to the status quo are prominent in the novel:

IT is a powerful dominant group that manipulates the planet of Camazotz into conformity. Even Charles Wallace falls prey and is hence persuaded to conform. It is thanks to Meg that she and her father and brother are able to break from conformity.[d]

According to Charlotte Jones Voiklis, the author's granddaughter, the story was not a simple allegory of communism; in a three-page passage that was cut before publication, the process of domination and conformity is said to be an outcome of dictatorship under totalitarian regimes, and of an intemperate desire for security in democratic countries.[21][22]

J. Fulton writes:

L'Engle's fiction for young readers is considered important partly because she was among the first to focus directly on the deep, delicate issues that young people must face, such as death, social conformity, and truth. L'Engle's work always is uplifting because she is able to look at the surface values of life from a perspective of wholeness, both joy and pain, transcending each to uncover the absolute nature of human experience that they share.[20](v 2, p 596)[e]

Conformity on Camazotz

[edit]Camazotz is a planet of extreme, enforced conformity, ruled by a disembodied brain called IT. Camazotz is similar to Earth, with familiar trees such as birches, pines, and maples, an ordinary hill on which the children arrive, and a town with smokestacks, which "might have been one of any number of familiar towns". The horror of the place arises from its ordinary appearance, endlessly duplicated. The houses are "all exactly alike, small square boxes painted gray", which, according to author Donald Hettinga, signals a comparison to "the burgeoning American suburbia", such as the post-war housing developments of Levittown, New York.[23][improper synthesis?] The people who live in the houses are similarly described as "mother figures" who "all gave the appearance of being the same".

W. Blackburn compared Camazotz to "an early sixties American image of life in a communist state", which Blackburn later dismissed.[24]

Feminism

[edit]A Wrinkle in Time has also received praise for empowering young female readers.[25] Critics have celebrated L'Engle's depiction of Meg Murry, a young, precocious heroine whose curiosity and intellect help save the world from evil.[26] The New York Times has described this portrayal as "a departure from the typical 'girls' book' protagonist – as wonderful as many of those varied characters are".[27]

In doing so, L'Engle has been credited for paving the way for other bright heroines, including Hermione Granger of the Harry Potter book series, as well as Katniss Everdeen of the Hunger Games trilogy.[26] Regarding her choice to include a female protagonist, L'Engle has stated in her acceptance speech upon receiving the Margaret Edwards Award, "I'm a female. Why would I give all the best ideas to a male?"[26]

Reception

[edit]At the time of the book's publication, Kirkus Reviews said:

Readers who relish symbolic reference may find this trip through time and space an exhilarating experience; the rest will be forced to ponder the double entendres.[28]

According to The Horn Book Magazine:

Here is a confusion of science, philosophy, satire, religion, literary allusions, and quotations that will no doubt have many critics. I found it fascinating ... It makes unusual demands on the imagination and consequently gives great rewards.[29]

In a retrospective essay about the Newbery Medal-winning books from 1956 to 1965, librarian Carolyn Horovitz wrote:

There is no question but that the book is good entertainment and that the writer carries the story along with a great deal of verve; there is some question about the depth of its quality.[30]

In a 2011 essay for Tor.com, American author and critic Mari Ness called A Wrinkle in Time

a book that refuses to talk down to its readers, believing them able to grasp the difficult concepts of mathematics, love and the battle between good and evil. And that's quite something.[31]

A 2004 study found that A Wrinkle in Time was a common read-aloud book for sixth-graders in schools in San Diego County, California.[32] Based on a 2007 online poll, the National Education Association listed the book as one of its "Teachers' top 100 books for children."[33] It was one of the "Top 100 chapter books" of all time in a 2012 poll by School Library Journal.[34]

In 2016, the novel saw a spike in sales after Chelsea Clinton mentioned it as influential in her childhood in a speech at the 2016 Democratic National Convention.[35]

Controversy

[edit]A Wrinkle in Time is on the American Library Association list of the 100 most frequently challenged books of 1990–2000 at number 23.[36] The novel has been accused of being both anti-religious and anti-Christian for its inclusion of witches and crystal balls, and for containing "New Age" spiritual themes that do not reflect traditional Christian teachings.[37][38]

According to USA Today, the novel was challenged in a school district in the state of Alabama due to the "book's listing the name of Jesus Christ together with the names of great artists, philosophers, scientists, and religious leaders when referring to those who defend Earth against evil."[37] The novel was also challenged in 1984 by an elementary school in Polk City, Florida when parents claimed that the novel promoted witchcraft.[39]

Regarding this controversy, L'Engle told The New York Times:

It seems people are willing to damn the book without reading it. Nonsense about witchcraft and fantasy. First I felt horror, then anger, and finally I said, 'Aw, the hell with it.' It's great publicity, really.[40]

Audio books

[edit]In 1994, Listening Library released an unabridged, 4 cassette audio edition read by the author.[41]

On January 10, 2012, Audible released a 50th anniversary edition recorded by Hope Davis.[42]

Film adaptations

[edit]In 2003, a television adaptation of the novel was made by a collaboration of Canadian production companies, to be distributed in the United States by Disney. The movie was directed by John Kent Harrison, with a teleplay by Susan Shilliday. It stars Katie Stuart as Meg Murry, Alfre Woodard as Mrs. Whatsit, Alison Elliott as Mrs. Who, and Kate Nelligan as Mrs. Which. In an interview with MSNBC / Newsweek, when L'Engle was asked if the film "met her expectations", she said, "I have glimpsed it ... I expected it to be bad, and it is."[43]

A theatrical feature film adaptation of the novel, by Walt Disney Pictures, was released in 2018. The film was directed by Ava DuVernay and written by Jennifer Lee and Jeff Stockwell. It stars Oprah Winfrey, Reese Witherspoon, Mindy Kaling, Chris Pine, Gugu Mbatha-Raw, Storm Reid, Michael Peña, and Zach Galifianakis.[44][45]

Plays

[edit]An adaptation by James Sie premiered at the Lifeline Theatre in Chicago in 1990, and returned to the stage in 1998 and 2017.[46]

John Glore adapted the novel as a play that premiered in 2010. It was written for 6 actors playing 12 parts. One actor plays Mrs Whatsit, the Man with Red Eyes, and Camazotz Man. Similarly, another performer plays the characters of Dr. Kate Murry, Mrs Who, Camazotz Woman, and Aunt Beast. The stage adaptation premiered in Costa Mesa, California, with productions in Bethesda, Maryland; Cincinnati; Philadelphia; Orlando; Portland, Oregon; and other cities.[47][48]

An adaptation by Tracy Young premiered at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in April 2014, with productions at colleges and theaters around the U.S.[49]

Opera

[edit]In 1992, OperaDelaware (known for frequently adapting children's books) staged an opera based on A Wrinkle in Time written by Libby Larsen with a libretto by Walter Green. The review in Philly.com stated: "The composer does not place arias and set pieces, but conversational ensembles with spoken dialogue that made the young daughter's climactic but concise song about familial love all the more imposing."[50][51]

Graphic novel

[edit]In 2010, Hope Larson announced that she was writing and illustrating the official graphic novel version of the book. This version was published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux in October 2012.[52][53]

Further reading

[edit]- Soares, Manuela (2003). A Reading Guide to A Wrinkle in Time. Scholastic BookFiles. ISBN 0-439-46364-5.

- Chase, Carole F. (1998). Suncatcher: A study of Madeleine L'Engle and her writing. Innisfree Press. p. 170. ISBN 1-880913-31-3.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The biennial, international Hans Christian Andersen Award for children's writing was inaugurated in 1956, recognizing a single book published during the preceding two years. Since the first three renditions – that is, from 1962 – it has recognized a living author for a lasting contribution, considering his or her complete works. Nevertheless, a "Runner-Up List" with single book titles was published from 1960–1964.[54]

- ^ The effect of Meg's rescue of Charles Wallace on IT and the fate of the people of Camazotz are not shown or described (although Meg hopefully wonders if IT would shrivel up and die if she could love it). After they vanish at the end of the book, the three Mrs. Ws never re‑appear in L'Engle's stories.

- ^ L'Engle was herself the official writer-in-residence at New York City's Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Divine, which is known for its prominent position in the liberal wing of the Episcopal Church.[17]

- ^ ... the importance of both individual initiative and family interaction is a thematic thread. L'Engle made both the Murry adults highly talented, both intellectually and scientifically. This was atypical of fiction published in the 1950s, when the book was written. Female characters rarely were featured as intellectuals or scientists. L'Engle has been praised for this departure as well as for her creation of strong female characters. Critics even suggested that in making Meg the protagonist in A Wrinkle in Time, L'Engle opened the door for the many female protagonists who have appeared in more recent fantasy and science fiction. — J. Fulton (2002)[20](v 2, p 597–598)

- ^ Madeleine L'Engle's view of the universe was changed by the work of such well-known physicists as Albert Einstein and Max Planck. She expressed her new perspective in A Wrinkle in Time ... — J. Fulton (2002)[20](v 2, p 596)

References

[edit]- ^ A Wrinkle in Time. LC Online Catalog. U.S. Library of Congress. 1962. ISBN 9780374386139. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ a b L'Unji, Madeleine (2007). Go Fish: Questions for the Author. A Wrinkle in Time (Report). New York: Square Fish. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-312-36754-1.

- ^ Chase, Carole F. (1998). Suncatcher: A study of Madeleine L'Engle and her writing. Philadelphia: Innisfree Press. p. 170. ISBN 1-880913-31-3.

- ^ a b c Thomas (2006). "L'Engle, Madeleine". In Dowling, E. M.; Scarlett, W. G. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Religious and Spiritual Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications – via Credo Reference.

- ^ a b Cullinan, Bernice E. (2005). "L'Engle, Madeleine". In Cullinan, B. E.; Person, D. G. (eds.). Continuum Encyclopedia of Children's Literature. London: Continuum – via Credo Reference.

- ^ a b c d e Bailey, Sarah Pulliam (March 8, 2018). "Publishers rejected her, Christians attacked her: The deep faith of A Wrinkle in Time author Madeleine L'Engle". Biography in Context. The Washington Post. Retrieved November 29, 2018 – via Gale Group.

- ^ a b c d Martin, Douglas (September 8, 2007). "Madeleine L'Engle, writer of children's classics, is dead at 88". The New York Times (obituary). ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ "14 things to know about Madeleine L'Engle's life and legacy". Office of Alumnae Relations. alumnae.smith.edu. Smith College. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ L'Engle, Madeleine (1987) [1962]. A Wrinkle in Time (25th anniversary collectors' limited ed.). New York, NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. pp. viii–ix.

- ^ a b c L'Engle, Madeleine (January 1972). A Circle of Quiet. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. pp. 5–6, 21, 66, 217–218. ISBN 0-374-12374-8.

- ^ a b Melcher, Michael (September 8, 2007). "What I Learned from Madeleine L'Engle". The Huffington Post. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Gooding, Richard (2021). ""We do not have whims on the moon": A Wrinkle in Time, The Lotus Caves, and the Problem of American Exceptionalism in 1960s Science Fiction for Children". The Lion and the Unicorn. 45 (3): 291–308. doi:10.1353/uni.2021.0025. ISSN 1080-6563. S2CID 248406307.

- ^ a b c L'Engle, Madeleine (2004). "A special message from Madeleine L'Engle". A Wrinkle in Time. Teachers @ Random. Random House. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ "A Wrinkle in Time's cover art". AbeBooks. June 3, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ "It's time to read A Wrinkle in Time". Square Fish Books. 2007. Archived from the original on March 3, 2007. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ^ a b Simpson, J.B. (1988). "Humankind – Religion – Spirituality". Simpson's Contemporary Quotations. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin – via credoreference.com.

- ^ Chan, Sewell (November 30, 2008). "Repaired after fire, cathedral reopens". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e Hettinga, Donald (May–June 1998). "A wrinkle in faith: The unique spiritual pilgrimage of Madeleine L'Engle". Books & Culture: A Christian Review. Christianity Today.

- ^ a b Stott, Jon (Fall 1977). "Midsummer night's dreams: Fantasy and self-realization in children's fiction". The Lion and the Unicorn. 1 (2): 25–39. doi:10.1353/uni.0.0401. S2CID 145776252.; cited by Hettinga[18](pp 27, 30)

- ^ a b c Fulton, Jean C. (2002). "A Wrinkle in Time". In Fiona Kelleghan (ed.). Classics of Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature. Vol. 2. Pasadena, CA: Salem Press. p. 596. Archived from the original on January 3, 2014. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- ^ "A Wrinkle in Time excerpt". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Maloney, Jennifer (April 16, 2015). "A new Wrinkle in Time". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Hettinga, Donald R. (1993). Presenting Madeleine L'Engle. New York, NY: Twayne Publishers. p. 27. ISBN 0-8057-8222-2.

- ^ Blackburn, William (1985). "Madeleine L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time: Seeking the original face". Touchstones: Reflections on the Best in Children's Literature. 1: 125. Cited by Hettinga[18](p 27)

- ^ Doll, Jen (January 30, 2017). "11 Young-Adult Books for Stoking the Feminist Fire". The Strategist. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c Escobar, Natalie (January 2016). "The remarkable influence of A Wrinkle in Time". Smithsonian magazine. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ Paul, Pamela (January 27, 2012). "A Wrinkle in Time and its sci-fi heroine". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ "A WRINKLE IN TIME by Madeleine L'Engle". Kirkus Reviews. March 1, 1962. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ^ "What did we think of ... ?". The Horn Book Magazine. January 24, 1999. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ^ Horovitz, Carolyn (1965). "Only the Best". In Kingman, Lee (ed.). Newbery and Caldecott Medal Books: 1956-1965. Boston: The Horn Book, Incorporated. p. 159. LCCN 65-26759.

- ^ Ness, Mari (December 15, 2011). "There is such a thing as a tesseract: A Wrinkle in Time". Tor.com. Macmillan. Archived from the original on May 11, 2022. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ Fisher, Douglas; et al. (2004). "Interactive read-alouds: Is there a common set of implementation practices?" (PDF). The Reading Teacher. 58 (1): 8–17. doi:10.1598/RT.58.1.1. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 7, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ "Teachers' top 100 books for children". National Education Association. 2007. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Bird, Elizabeth (July 7, 2012). "Top 100 chapter book poll results". A Fuse #8 Production (blog). School Library Journal. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Brogan, Jacob (July 29, 2016). "The book Chelsea Clinton touted as her childhood favorite is now outselling Trump's Art of the Deal". Slate. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ "The 100 most frequently 'challenged' books of 1990–2000". Banned Books Week. American Library Association. 2007. Archived from the original on April 4, 2007. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ a b Matheson, Whitney (September 29, 2004). "Some of the best books in life are ... banned?". USA Today. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Baron, Henry J. (October 1993). "Wrinkle on Trial" (PDF). Christian Educators Journal. 33 (1): 10–11.

- ^ Nicolaou, Elena (March 2018). "Why is A Wrinkle In Time still so frequently banned?". Refinery29. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ "Why was A Wrinkle in Time book banned - movie trailer, cast and UK release date". Metro. March 6, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ L'Engle, Madeleine (1994). A Wrinkle in Time (audiobook ed.). Listening Library. ISBN 0-8072-7587-5.

- ^ L'Engle, Madeleine (January 10, 2012). A Wrinkle in Time. Davis, Hope; du Vernay, Ava (narrators); L'Engle, Madeleine (introduction) (audible 50th ann. ed.). Random House Audio. ISBN 9780307916600. ISBN 030791660X

- ^ Henneberger, Melinda (May 7, 2003). "'I dare you': Madeleine L'Engle on God, 'The da Vinci Code' and aging well". Newsweek. MSNBC. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (November 1, 2016). "Zach Galifianakis, Andre Holland, and Pan star Levi Miller join A Wrinkle in Time". Variety. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ Gettell, Oliver (November 1, 2016). "A Wrinkle in Time adds Zach Galifianakis, André Holland, Rowan Blanchard". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ Bommer, Lawrence (October 15, 1998). "A Wrinkle in Time". The Chicago Reader. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- ^ Carpenter, Susan (February 28, 2010). "Wrinkle in Time takes leap to South Coast Rep stage". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Wren, Celia (December 9, 2010). "A Wrinkle wrought smoothly for the stage". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "A Wrinkle in Time". Oregon Shakespeare Festival. 2014 season plays. Ashland, OR. 2014.

- ^ Webster, Daniel (March 30, 1992). "'Wrinkle In Time' At Playhouse, Premiered By Operadelaware". Philly.com. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- ^ "Libby Larsen - Opera". libbylarsen.com. Archived from the original on May 1, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ^ "A first look at Hope Larson's A Wrinkle in Time". Comic Book Resources. 2010. Archived from the original on August 29, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ Arrant, Chris (August 31, 2010). "Hope Larson talks comics". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Glistrup, Eva (2002). "Half a century of the Hans Christian Andersen awards". The Hans Christian Andersen Awards, 1956–2002. International Board on Books for Young People / Gyldendal. pp. 14–21, esp. 15–16. Retrieved July 22, 2013 – via Austrian Literature Online (literature.at). This source does not identify those runners-up or report their number.

External links

[edit]- "A Wrinkle in Time". The Open Critic (review). Archived from the original on September 26, 2007.

- A Wrinkle in Time title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- A Wrinkle in Time (TV) (mini) at IMDb

- "A Wrinkle in Time". Official book site for the May 2007 release. May 2007.

- 1962 American novels

- Time Quintet

- American fantasy novels adapted into films

- Novels by Madeleine L'Engle

- Newbery Medal–winning works

- Science fantasy novels

- Young adult fantasy novels

- Children's fantasy novels

- Children's science fiction novels

- Christian science fiction

- Feminist science fiction novels

- Space exploration novels

- 1962 science fiction novels

- 1962 fantasy novels

- Books with cover art by Leo and Diane Dillon

- Farrar, Straus and Giroux books

- Fiction about wormholes

- Novels set on fictional planets

- Novels about time travel

- 1962 children's books

- American novels adapted into television shows

- Science fiction novels adapted into films

- American novels adapted into plays

- Novels adapted into operas

- Novels adapted into comics

- Children's books about time travel

- Children's books set on fictional planets

- Young adult science fiction novels