The Blazing World

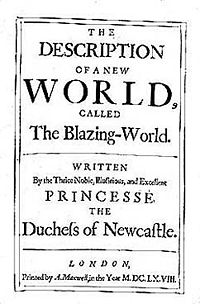

Title page of Margaret Cavendish's The Description of a New World, Called The Blazing-World, reprinted 1668 [originally published 1666] | |

| Author | Margaret Cavendish |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction, utopian |

| Published | 1666 |

| Publisher | Anne Maxwell |

| Publication place | England |

The Description of a New World, Called The Blazing-World, better known as The Blazing World, is a 1666 work of prose fiction by the English writer Margaret Cavendish, the Duchess of Newcastle. Feminist critic Dale Spender calls it a forerunner of science fiction.[1] It can also be read as a utopian work.[2]

Story

[edit]

As its full title suggests, Blazing World is a fanciful depiction of a satirical, utopian kingdom in another world (with different stars in the sky) that can be reached via the North Pole. According to novelist Steven H. Propp, it is "the only known work of utopian fiction by a woman in the 17th century, as well as an example of what we now call 'proto-science fiction' — although it is also a romance, an adventure story, and even autobiography."[3]

The Blazing World opens with a sonnet written by the author's husband, William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, which celebrates her imaginative powers. The sonnet was followed by a letter to the reader written by Margaret Cavendish herself. In the letter to the reader, Cavendish divides Blazing World into three parts. The first part being “romancical”, the second “philosophical”, and the third “fancy” or “fantastical”.[4] She also explains the joint publishing of Blazing World with the more intellectual Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy.

The first “romancical” section describes a young woman from the Kingdom of ESFI (an acronym for England, Scotland, France, and Ireland) being kidnapped onto a boat by a spurned lover. The gods, unsatisfied by the kidnapping, blow the boat to the North Pole, where all of the crew except the young woman die of hypothermia. The ship floats into a parallel world populated by talking animal-human hybrids, the "Blazing World". The strange young woman is worshipped as a goddess, despite her pleas that she is mortal, and is made Empress of the Blazing World.

The second “philosophical” section describes the Empress' knowledge and interest in the natural sciences and philosophy. She consults on these matters with a variety of human-animal hybrids, each group of which is specialized in a specific field. She praises some of these guild-like groups, and chastises others. She also imposes a new religion onto the Blazing World. Homesick, she consults immaterial spirits to tell her news from home, and enlists their assistance to write her own Cabbala. The spirits suggest the Duchess of Newcastle to be the best scribe for the project.

The final "fantastical" section begins as the Empress and Duchess become close friends over the writing of the Cabbala. They visit England together, with the Empress' soul inhabiting the Duchess' body, and the Duchess solicits help from Fortune for her unlucky husband. In the Blazing World, the Duchess mounts an impassioned defense of her husband at a court hearing with the virtues, although the outcome of the legal process is inconclusive. The Duchess departs the Blazing World for her home, and advises the Empress to return the Blazing World to its original balance.

When the spirits inform the Empress that ESFI has been destroyed in war, the Empress and the Duchess reunite to plan an invasion of ESFI. The Empress clothes herself in gemstones and invades with fantastical technologies. The armies of ESFI think her an angel, and the Empress compels them to return power to ESFI's righteous King. The Empress and the Duchess have one last extended conversation, and depart to their respective homes. The Empress returns the Blazing World to its original harmony, without her implemented religion.

Finally, Cavendish ends Blazing World with an Epilogue to the Reader. In this Epilogue she describes her reasons for writing The Blazing World. She compares creating The Blazing World to the conquests of Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar.[5]

The work was initially published as a companion piece to Cavendish's Observations upon Experimental Philosophy[6] and thus functioned as an imaginative component to what was otherwise a reasoned endeavor in 17th-century science. It was reprinted in 1668.[6]

Genre and implications

[edit]Scholar Nicole Pohl of Oxford Brookes University has argued that Cavendish was accurate in her categorisation of the work as "a 'hermaphroditic' text". Pohl points to Cavendish's confrontations of seventeenth century norms, with regard to such categories as science, politics, gender, and identity. Pohl argues that her willingness to question society's conceptions while discussing topics that were considered in her era best left to male minds, allows her to escape into an exceptional gender-neutral discussion of said topics, creating what Pohl labels, "a truly emancipatory poetic space."[7]

Northeastern University professor Marina Leslie remarks that readers have noted that The Blazing World serves as a departure from the habitually male-dominated field of utopian writing. While some readers and critics may interpret Cavendish's work as being restricted by these characteristics of the genre of utopia, Leslie suggests approaching interpretations of the work while remembering Cavendish as one of the first, more outspoken feminists in history, and especially in early writing. Leslie contends that in this sense, Cavendish utilised the utopian genre to discuss issues such as "female nature and authority" in a new light, while simultaneously expanding the utopian genre itself.[8]

Dr. Delilah Bermudez Brataas elaborates on utopias' impact on gender and sexuality in her thesis for Tufts University. She points out that initially, utopias were sexually fluid worlds. Therefore, they challenged gender conventions. Cavendish's Blazing World demonstrates how sexual and gender-fluid these spaces are, mainly when women write them. Brataas elaborates on this statement further and describes the genre's appeal in earlier times. This period, combined with gender conventions at the time, makes utopia an appealing genre for Cavendish. Utopias offer women a space that can be primarily feminine and makes them feel empowered. Writing a utopia offered Cavendish the opportunity to create a world of her own, one over which she has complete agency and no limits. In her epigraph, Cavendish even reminds the reader that she owns this world and suggests that they are unwelcome and should create their own if they dislike it. Brataas points out how her decisions when building this world reflect her gender ideals, such as spaces for women's education and women as independent figures and authorities.[9]

Leslie also believes that The Blazing World incorporates many different genres, "which include not only travel narrative and romance but also utopia, epic, biography, cabbala, Lucianic fable, Menippean satire, natural history, and morality play, among others…”[10] Oddvar Holmesland of University of Edinburgh agrees that The Blazing World is creative in its genres, writing that "the term 'hybridisation' aptly captures Cavendish's method of blending established genres and categories into a new order, and of presenting her fantasy empire as versimilar."[11]

University of Georgia professor Sujata Iyengar points out the importance of the fact that The Blazing World is clearly fictional, a stark contrast to the scientific nature of the work it is attached to. Iyengar notes that writing a work of fiction allowed Cavendish to create a new world in which she could conceive of any possible reality. Such liberty, Iyengar argues, allows Cavendish to explore ideas of rank, gender, and race that directly clash with commonly held beliefs about servility in her era. Iyengar goes as far to say that Cavendish's newfound liberty within fictional worlds provides her an opportunity to explore ideas that directly conflict with those that Cavendish writes about in her nonfiction writing.[12]

Jason H. Pearl of Florida International University considers The Blazing World as one of the earliest examples of the novel, "adding the modifier 'early'...to indicate a period in the novel's history when experimentation was more common, when strange incidents conveyed in strange ways could be expected from prose fiction." Pearl also believes it to contain an "interaction and opposition between two tributary forms: the lunar voyage, a subgenre of utopian writing, and natural philosophy, which helped inform notions of possibility and plausibility in representations of the natural world." However, Pearl also considers it "a revision to the lunar voyage ... one of its revisions is to pull the destination earthward, literally and figuratively, making its various possibilities of difference somehow more accessible."[13]

The University of Memphis professor Catherine Gimelli Martin compares The Blazing World to another early example of the genre: Thomas More’s Utopia. She describes Cavendish’s focus as knowledge, whereas More’s is money. Unlike More, Cavendish uses gold in her world as a tool for decoration yet devalues it entirely otherwise. Additionally, she forbids commoners from using gold at all. Martin suggests that in The Blazing World, this class system eliminates any competition for gold like that seen and discussed in More’s Utopia.[14]

World

[edit]Jason Pearl has commented on the surrealism of the world, as well as (paradoxically) its similarity to our own. He writes, “The Lady’s experience is described as ‘so strange an adventure,’ in ‘so strange a place, and amongst such wonderful kind of creatures,’ ‘none like any of our world’...It seems anything is possible here,” and that, “near as it is, the Blazing World boasts a multitude of otherworldly marvels," but also believes that "the interstitial passageway exists as a wrinkle in space, a connecting disconnection that permits the Blazing World’s narrow reachability and legitimises its radical differences.”[13] By "interstitial passageway," Pearl is referring to the unseen, unexplained path the protagonist and her captors traverse in the beginning of the story to reach the Blazing World.

Political views

[edit]Throughout The Blazing World, the Empress asserts that a peaceful society can only be attained through the lack of societal divisions. To eliminate potential division and maintain social harmony in the society the text imagines, Cavendish constructs a monarchical government.[15] Unlike a democratic government, Cavendish believes only an absolute sovereignty can maintain social unity and stability because the reliance on one authority eliminates separations of power.[16] To further justify the monarchical government, Cavendish draws upon philosophical and religious arguments. She writes, "it was natural for one body to have one head, so it was also natural for a politic body to have but one governor … besides, said they, a monarchy is a divine form of government, and agrees most with our religion."[17]

Cavendish's political views are similar to those of English philosopher Thomas Hobbes. In his 1651 book, Leviathan, Hobbes famously upholds the notion that a monarchical government is a necessary force in preventing societal instability and "ruin",[15] As a notable contemporary of Cavendish, Hobbes' influence on her political philosophy is apparent.[18] In The Blazing World, Cavendish even directly mentions his name while cataloguing famous writers: "Galileo, Gassendus, Descartes, Helmont, Hobbes, H. More, etc".[19]

Influence

[edit]Blazing World was originally published as a conjoined text along with Cavendish's Observations on Experimental Philosophy, which was a direct response to scientist Robert Hooke's Micrographia which was published only a year before. Advances in the field of science and philosophy in the early modern period had a huge influence on Cavendish and were a major component of The Descriptions of a New World, Called the Blazing World.[20] This influence can be seen directly in Blazing World, with nearly half the book consisting of descriptions of the Blazing World, its people, philosophies, and inventions. One of these inventions is a microscope, which Cavendish critiques alongside the experimental method itself in the Blazing World.[21] This integration of scientific advances could be one of the reasons Blazing World is considered by some to be the first sci-fi novel.

In Alan Moore's graphic novels chronicling the adventures of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, the Blazing World was identified as the self-same idyllic realm from which the extra-dimensional traveller Christian, a member of the first League led by Duke Prospero, had come in the late 1680s. The league disbanded when Christian returned to this realm, and it was to where Prospero, Caliban, and Ariel also departed many years later.

In China Miéville's Un Lun Dun, a library book entitled A London Guide for the Blazing Worlders is mentioned, suggesting that travel between the two worlds is not all one-way.

J.G. Ballard wrote a quartet of catastrophe novels, three of which echo the title of The Blazing World: The Drowned World (1962), The Burning World (1964; republished as The Drought in 1965), and The Crystal World (1966).

In 2014, Siri Hustvedt published the novel The Blazing World, in which she describes Harriet Burden's brilliant but convoluted attempts at gaining recognition from the male-dominated New York City art scene. Hustvedt has Burden refer to Margaret Cavendish as a rich source of inspiration at many occasions. Nearing the end of her life, Burden is comforted by Cavendish's work: "I am back to my blazing mother Margaret" (p. 348), she writes in her notebook.

In 2021, Carlson Young released the film The Blazing World, which she directed, co-wrote, and starred in. The film's credits state that it is "inspired by Margaret Cavendish and other dreams".[22]

In 2023 the book was adapted for the stage at Theater & Orchester Heidelberg, Germany.[23]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Spender, Dale (1986). Mothers of the Novel. London: Pandora Press. p. 43. ISBN 0863580815.

- ^ Khanna, Lee Cullen. "The Subject of Utopia: Margaret Cavendish and Her Blazing-World." Utopian and Science Fiction by Women: World of Difference. Syracuse: Syracuse UP, 1994. 15–34.

- ^ Steven H. Propp, Utopia on the 6th Floor: Work, Death, and Taxes — Part 2, Bloomington, IN, iUniverse, 2004; p. 383.

- ^ Whitaker, Katie (2003). Mad Madge : the extraordinary life of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, the first woman to live by her pen. New York: Basic Books. p. 282. ISBN 0-465-09164-4. OCLC 55206694.

- ^ Newcastle, Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of,?-1674 (1994). The blazing world and other writings. Kate Lilley. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-043372-4. OCLC 31364072.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Cavendish, Margaret (2016). The description of a new world, called the blazing world. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press. p. 21. ISBN 9781554812424.

- ^ Clucas, Stephen (2003). A princely brave woman : essays on Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle. Ashgate. ISBN 0754604640. OCLC 49240098.

- ^ LESLIE, MARINA (1996). "Gender, Genre and the Utopian Body in Margaret Cavendish's Blazing World". Utopian Studies. 7 (1): 6–24. JSTOR 20719470.

- ^ "PDF | Shakespeare and Cavendish: Engendering the Early Modern English Utopia. | ID: 0v838b479 | Tufts Digital Library". dl.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2021-05-09.

- ^ Leslie, Marina. "Mind the Map: Fancy, Matter, and World Construction in Margaret Cavendish's "Blazing World"". Renaissance and Reformation.

- ^ Holmesland, Oddvar. "Margaret Cavendish's Anthropocene Worlds". New Literary History.

- ^ Iyengar, Sujata (2002-09-01). "Royalist, Romancist, Racialist: Rank, Gender, and Race in the Science and Fiction of Margaret Cavendish". ELH. 69 (3): 649–672. doi:10.1353/elh.2002.0027. ISSN 1080-6547. S2CID 162125904.

- ^ a b Pearl, Jason H. (2014). Utopian Geographies and the Early English Novel. University of Virginia Press.

- ^ Martin, Catherine Gimelli (2018-11-12). "All That Glitters: Devaluing the Gold Standard in the Utopias of Thomas More, Francis Bacon, and Margaret Cavendish". Renaissance and Reformation. 41 (3). doi:10.33137/rr.v41i3.31557. ISSN 2293-7374.

- ^ a b Boyle, Deborah (2006-01-01). "Fame, Virtue, and Government: Margaret Cavendish on Ethics and Politics". Journal of the History of Ideas. 67 (2): 251–290. doi:10.1353/jhi.2006.0012. JSTOR 30141878. S2CID 144505763.

- ^ Boyle, Deborah. "Fame, Virtue, and Government: Margaret Cavendish on Ethics and Politics." Journal of the History of Ideas. University of Pennsylvania Press, 22 May 2006. Web. 02 June 2017.

- ^ Cavendish, Margaret (1994). The Blazing World & Other Writings. Penguin Classics. p. 134. ISBN 9780140433722.

- ^ Duncan, Stewart (2012-01-01). "Debating Materialism: Cavendish, Hobbes, and More". History of Philosophy Quarterly. 29 (4): 391–409. JSTOR 43488051.

- ^ Cavendish, Margaret (1994). The Blazing World & Other Writings. Penguin Classics. p. 181. ISBN 9780140433722.

- ^ Keller, Eve (1997). "Producing Petty Gods: Margaret Cavendish's Critique of Experimental Science". ELH. 64 (2): 447–471. doi:10.1353/elh.1997.0017. JSTOR 30030144. S2CID 161306367.

- ^ Borlik, Todd (2008). Philosophies of Technology: Francis Bacon and his Contemporaries. BRILL. pp. 231–250. ISBN 9789047442318.

- ^ "'The Blazing World' Review: Carlson Young's Exhaustively Art-Directed but Enervating Adult Fantasy". 3 February 2021.

- ^ "The Blazing World - Productions - Theater und Orchester Heidelberg". www.theaterheidelberg.de. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

References

[edit]- Paper bodies: a Margaret Cavendish reader. Ed. Sylvia Bowerbank and Sara Mendelson. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 2000. ISBN 1-55111-173-X

External links

[edit]- The Blazing World at Standard Ebooks

- The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing-World at Project Gutenberg

The Blazing World public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Blazing World public domain audiobook at LibriVox- A digitization of the British Library's copy of The Description of a New World, Called The Blazing-World (1668 edition) is available at Google Books and the Internet Archive; both digital copies are indexed under the 1666 edition title Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy: To which is Added, the Description of a New Blazing World.