Woman in Gold (film)

| Woman in Gold | |

|---|---|

UK theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Simon Curtis |

| Written by | Alexi Kaye Campbell |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Ross Emery |

| Edited by | Peter Lambert |

| Music by | |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 109 minutes[3] |

| Countries |

|

| Languages | English German |

| Budget | $11 million[1] |

| Box office | $61.6 million[1] |

Woman in Gold is a 2015 biographical drama film directed by Simon Curtis and written by Alexi Kaye Campbell. The film stars Helen Mirren, Ryan Reynolds, Daniel Brühl, Katie Holmes, Tatiana Maslany, Max Irons, Charles Dance, Elizabeth McGovern, and Jonathan Pryce.

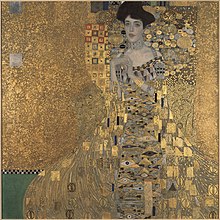

The film is based on the true story of Maria Altmann, an elderly Jewish refugee living in Cheviot Hills, Los Angeles, who, together with her young lawyer, Randy Schoenberg, fought the government of Austria for almost a decade to reclaim Gustav Klimt's iconic painting of her aunt Adele Bloch-Bauer, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, which was stolen from her relatives by the Nazis in Vienna just prior to World War II. Altmann took her legal battle all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States, which ruled on the case Republic of Austria v. Altmann (2004).

The film was screened in the Berlinale Special Galas section of the 65th Berlin International Film Festival on 9 February 2015 and was released in the United Kingdom on 10 April 2015 and in the United States on 1 April.[5]

Plot

[edit]In a series of flashbacks, Maria Altmann recalls the Anschluss, the arrival of Nazi forces in Vienna, the persecution of the Jewish community, and the looting and pillaging by the Nazis of Jewish families. Maria and her family attempt to flee to the United States. While Maria and her husband are successful, she is forced to abandon her parents in Vienna.

In 1998, living in Los Angeles, an elderly and widowed Altmann attends the funeral of her sister. She discovers letters in her sister's possession dating to the late 1940s, which reveal an attempt to recover artwork owned by the Bloch-Bauer family that was left behind during the family's flight for freedom and stolen by the Nazis. Of particular note is a painting of Altmann's aunt, Adele Bloch-Bauer, now known in Austria as the "Woman in Gold".

Altmann enlists the help of E. Randol Schoenberg (the son of her close friend, Barbara), a lawyer with little experience, to make a claim to the art restitution board in Austria. Reluctantly returning to her homeland, Altmann discovers that the country's minister and art director are unwilling to part with the painting, which they feel has become part of the national identity. Altmann is told that the painting was legitimately bequeathed to the gallery by her aunt. Upon further investigation by her lawyer and Austrian journalist Hubertus Czernin, this claim proves to be wrong as the alleged will is invalid since her aunt did not own the painting, the artist's fee having been paid by Altmann's uncle. Adele Bloch-Bauer wanted the painting to go to the museum at her husband's death but it was taken from him by the Nazis and placed in the museum by a Nazi-collaborating curator, well before his death. Schoenberg files a challenge with the art restitution board, but it was denied and Altmann did not have the money needed to challenge the ruling. Defeated, she and Schoenberg return to the United States.

Months later, happening upon an art book with "Woman in Gold" on the cover, Schoenberg has an epiphany. Using a narrow rule of law and precedents in which an art restitution law was retroactively applied, Schoenberg files a claim in US court against the Austrian government contesting their claim to the painting. An appeal goes to the Supreme Court of the United States, where in the matter of Republic of Austria v. Altmann, the court rules in Altmann's favor, which results in the Austrian government attempting to persuade Altmann to retain the painting for the gallery, which she refuses. After a falling out over the issue of returning to Austria for a second time to argue the case, Altmann agrees for Schoenberg to go and argue the case in front of a panel of three arbiters in Vienna.

In Austria, the panel hears the case, during which Schoenberg reminds them of the Nazi regime's crimes. He implores the arbitration panel to think of the meaning of the word "restitution" and to look past the artwork hanging in art galleries to see the injustice to the families who once owned such great paintings and were forcibly separated from them by the Nazis. Unexpectedly, Altmann arrives during the session, indicating to Czernin that she came to support her lawyer. After considering both sides of the dispute, the arbitration panel rules in favour of Altmann, returning her paintings. The Austrian government representative makes a last-minute proposal begging Altmann to keep the paintings in the Belvedere against generous compensation. Altmann refuses and elects to have the painting moved to the United States with her ("They will now travel to America like I once had to as well") and takes up an offer made earlier by Ronald Lauder to acquire them for his New York gallery to display the painting on condition that it be a permanent exhibit.

Cast

[edit]- Helen Mirren[6] as Maria Altmann

- Tatiana Maslany[6] as young Maria Altmann

- Ryan Reynolds as Randol 'Randy' Schoenberg

- Daniel Brühl as Hubertus Czernin

- Katie Holmes[7] as Pam Schoenberg

- Max Irons[8] as Fredrick "Fritz" Altmann

- Allan Corduner as Gustav Bloch

- Henry Goodman as Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer

- Nina Kunzendorf as Therese Bloch

- Antje Traue as Adele Bloch-Bauer[7]

- Charles Dance[8] as Sherman

- Elizabeth McGovern[8] as Judge Florence-Marie Cooper

- Jonathan Pryce[8] as Chief Justice William Rehnquist

- Frances Fisher as Barbara Schoenberg[9]

- Tom Schilling as Heinrich

- Moritz Bleibtreu[8] as Gustav Klimt

- Justus von Dohnányi as Mr. Dreimann

- Ludger Pistor as Rudolph Wran

- Olivia Silhavy as Minister Elisabeth Gehrer

- Rupert Wickham as Arbitrator

Production

[edit]On 15 May 2014, Tatiana Maslany was cast in a principal role as the younger version of Helen Mirren's character, appearing in the Second World War flashbacks.[6] On 29 May Katie Holmes joined the cast of the film.[7] On 30 May Max Irons, Charles Dance, Elizabeth McGovern, Jonathan Pryce, Moritz Bleibtreu and Antje Traue joined the cast of the film.[8] On 9 July Frances Fisher joined the film to play Reynolds' character's mother.[9] This marks the second time both Mirren and Holmes have starred in a film together, the previous being the Kevin Williamson film Teaching Mrs. Tingle, in 1999.

The reproduction of the key painting, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, was painted by scenic artist Steve Mitchell, who spent five weeks making the re-creation. He also made a partly finished version as well as a partial version for a close-up.[10]

Filming

[edit]Principal photography began on 23 May 2014 and lasted for eight weeks in the United Kingdom, Austria, and the United States.[8][11] On 16 June the filming was underway in London.[12] On 9 July the filming was reportedly underway in Los Angeles.[9]

The Vienna airport scenes were filmed in the UK at Shoreham Airport in West Sussex.[citation needed]

Reception

[edit]

Box office

[edit]Woman in Gold grossed $33.3 million in North America and $28.3 million in other territories for a total gross of $61.6 million, against a budget of $11 million.[1]

In the film's limited release weekend, 3–5 April, it grossed $2.1 million from 258 cinemas. In its wide release weekend, expanding to 1,504 cinemas on 10 April it grossed $5.5 million, finishing 7th at the box office.

Critical response

[edit]On Rotten Tomatoes, the film had a rating of 57% based on 152 reviews, with an average rating of 6/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Woman in Gold benefits from its talented leads, but strong work from Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds isn't enough to overpower a disappointingly dull treatment of a fascinating true story."[13] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 51 out of 100, based on 31 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[14] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[15]

Accolades

[edit]Helen Mirren received a nomination for the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Leading Role.[16]

Historical accuracy

[edit]Altmann's efforts actually addressed five Klimt paintings owned by her family, including Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I and Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II, as well as three landscapes. The decisions by the US Supreme Court and the Austrian arbitrators covered all five paintings.

Film critics in Austria and Germany noted various deviations of the film from historical reality. Olga Kronsteiner from the Austrian daily Der Standard wrote that it was not Maria Altmann's lawyer, Randol Schönberg, who researched and initiated the restitution case, but Austrian journalist Hubertus Czernin, who had worked on a number of restitution files at the time, who found the decisive documents and subsequently informed Maria Altmann.[17]

Hubertus Czernin, who is depicted in the movie, is suggested to have been motivated by the fact that his father had been a member of the Nazi Party, but Stefan Grissemann from Austrian weekly Profil pointed out that his father's party membership was not known to Czernin until 2006, long after he had started to work on this and other restitution cases. In addition, Czernin's father was imprisoned by the Nazis late in the war for high treason.[citation needed]

Thomas Trenkler from the Viennese daily Kurier criticized the film's reference to a time limit for restitution claims in Austria, writing that there has never been such a time limit. He also wrote that his least favorite scene in the film was when Maria Altmann leaves her ailing father in Vienna in 1938. Despite the imminent danger, Maria Altmann stayed in Vienna, having said, "I would never have left my father! He died of natural causes in July 1938". Only then did she and her husband escape from Vienna.[18]

In June 2006, based on an earlier agreement between Altmann and Ronald Lauder (which was shown in the film), Altmann sold Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I to Lauder's Neue Galerie New York for $135 million ($204 million today), setting a new mark for most expensive painting (since surpassed).[19] Five months later, Altmann sold the companion Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II at auction (bought by Oprah Winfrey) for almost $88 million ($133 million today), then the third-highest priced painting.[20][21]

Gustav Bloch-Bauer had been loaned the famous "Gore Booth Baron Rothschild" Stradivarius cello (see List of Stradivarius instruments) by the Rothschild family,[22] which was looted by the Nazis in 1938 and retained by the German authorities until 1956.[23]

The film strongly suggests that during the oral argument in Republic of Austria v. Altmann, Chief Justice William Rehnquist (played by Jonathan Pryce) is won over by Schoenberg and supports him. In fact, Rehnquist dissented from the court's eventual decision in Altmann's favour, and it was actually Associate Justice David Souter who asked the questions that were portrayed in the movie instead of Rehnquist.[24]

See also

[edit]- Art repatriation

- "Provenance" (Numbers)

- The Rape of Europa, a 1994 book and 2006 film about the Nazi plunder of art

- Stealing Klimt, a documentary film that was the inspiration for Woman in Gold[25]

- Adeleswish.com. a documentary film that recounts the history of the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I and the other Klimt paintings taken from the Bloch-Bauers by the Nazis.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Woman in Gold (2015)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ Rosser, Michael (30 January 2015). "SquareOne acquires Woman In Gold for Germany, Austria". Screen International. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ "'Woman in Gold' (15)". British Board of Film Classification. 20 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "BFI Statistics 2015: UK independent films win audiences in a blockbuster box office year". British Film Institute. 28 January 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ Rosser, Michael (15 January 2015). "Berlin 2015: Woman in Gold, Life to world premiere in Gala strand". Screen Daily. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Nissim, Mayer (15 May 2014). "Orphan Black's Tatiana Maslany joins Helen Mirren in Woman in Gold". Digital Spy. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ^ a b c Fleming, Mike Jr. (29 May 2014). "Katie Holmes Joins 'Woman In Gold'". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Barraclough, Leo (30 May 2014). "Max Irons, Charles Dance, Elizabeth McGovern Join 'Woman in Gold'". Variety. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ a b c Yamato, Jen (9 July 2014). "Frances Fisher Joins Helen Mirren, Ryan Reynolds In 'Woman In Gold'". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ^ Gelt, Jessica (29 May 2015). "'Master Forgery' Tribune". Chicago Tribune. Section 4, pp. 1 & 7.

- ^ "Woman In Gold begins shoot". Screen Daily. 30 May 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ Siobhan (16 June 2014). "'Woman in Gold' filming underway in London". OnLocationVacations.com. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ "Woman in Gold". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Woman in Gold Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (12 April 2015). "'Furious 7' Becomes Highest-Grossing 'Fast & Furious' Sequel In 10 Days – Box Office". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

Critics have been so-so on it with a Rotten Tomatoes of 53%, however exit polls tell another story: Auds love it with an A CinemaScore.

- ^ "SAG Awards Nominations: Complete List". Variety. 9 December 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ Kronsteiner, Olga (29 May 2015). ""Die Frau in Gold": Faktentreue ist eine schlechte Dramaturgin" ["Woman in Gold": factual accuracy is bad drama]. Der Standard (in German). Vienna. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ Trenkler, Thomas (2 June 2015). "Der Fall "Goldene Adele", tendenziös erzählt" [The case of "Golden Adele", tendentiously told]. Kurier (in German). Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ Cohen, Patricia (30 March 2015). "The Story Behind 'Woman in Gold': Nazi Art Thieves and One Painting's Return". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Michaud, Christopher (19 January 2007). "Christie's stages record art sale". Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ Kazakina, Katya (8 February 2017). "Oprah Said to Snag $150 Million Selling Klimt to Chinese Buyer". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ Kirsta, Alix (10 July 2006). "Glittering prize". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ "1710 - Violoncello "Gore-Booth - Rothschild"". Archivio della Liuteria Cremonese. 23 March 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ https://www.oyez.org/cases/2003/03-13.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Woman in Gold (closing credits).

External links

[edit]- Woman in Gold at IMDb

- Adele's Wish, a documentary film that details Maria Altmann's struggle to recover her family's Klimt paintings

- Woman in Gold at IMDb

- Official screenplay

- Stealing Klimt, the documentary which inspired Simon Curtis to direct Woman in Gold

- Stolen Beauty, a 2017 historical fiction novel by Laurie Lico Albanese that tells the tales of Adele Bloch-Bauer and her niece Maria Altmann

- UC San Diego, Holocaust Living History Collection: Whatever Happened to Klimt’s Golden Lady? - with E. Randol Schoenberg

- 2015 films

- 2015 biographical drama films

- 2015 war drama films

- British biographical drama films

- British legal films

- British war drama films

- British courtroom films

- Films about the aftermath of the Holocaust

- BBC Film films

- Drama films based on actual events

- War films based on actual events

- British films based on actual events

- Films about human rights

- Films about old age

- Films about lawyers

- Films set in 1998

- Films set in 1999

- Films set in 2000

- Films set in 2004

- Films set in 2006

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in Vienna

- Films shot in Austria

- Jews and Judaism in Vienna

- Films shot in England

- Films shot in the United States

- Films directed by Simon Curtis

- Films scored by Hans Zimmer

- Films scored by Martin Phipps

- Art and cultural repatriation after World War II

- Gustav Klimt

- Films about the visual arts

- 2015 drama films

- 2010s English-language films

- 2010s British films

- English-language biographical drama films

- English-language war drama films