Winold Reiss industrial murals

The Winold Reiss industrial murals are a set of 16 tile mosaic murals displaying manufacturing in Cincinnati, Ohio. The works were created by Winold Reiss for Cincinnati Union Terminal from 1931 to 1932, and made up 11,908 of the 18,150 square feet of art in the terminal.[1] The murals were first installed in the train concourse of the terminal, which was demolished in 1974. Prior to the demolition, almost all were moved to the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport, nine of which were placed in air terminals which were themselves demolished in 2015. The nine works were then relocated to the exterior of the Duke Energy Convention Center, where they stand today.[2] Two murals depicting the Rookwood Pottery Company never left the terminal; they were moved to the Cincinnati Historical Society's special exhibits gallery in 1991.[3]

History

[edit]

Reiss was paid $21,000 for the murals.[2] There were four stages to their creation - an initial photograph, a simple illustration on 30 x 22 inch paper with Conté crayons (sometimes combining multiple photographs), followed by the maquette - 1/3 size, and the final mosaic pieces.[4][5]

In 1931, he began taking photographs in factories, and then made the studies from them.[6] He sent the studies to the Ravenna Mosaic Company of New York and St. Louis, which created the tiles for the murals.[1] The 1/3 scale works were photographically enlarged to the full size, and the shop-drawings were traced in reverse, cut up into smaller pieces for craftsmen to add tiles - the most complicated areas to the most skillful artisans. Reiss lived in New York at the time and regularly visited to supervise the progress. They were then packed up and shipped to Cincinnati.[4]

Around 1932, Ravenna craftsmen and local laborers began to lay the works out on the terminal floor, assemble the works, and install them.[4] All sixteen were placed in the train concourse of the terminal, with the north wall displaying piano making, radio broadcasting, roofing manufacture, tanning, airplane manufacture, ink making, and laundry machine manufacture. The south wall displayed meat packing, drug and chemical processing, printing and publishing, foundry-products operations, sheet-steel making, soap making, and machine tool manufacture.[7] The two Rookwood Pottery murals were installed in corners of the concourse, above the offices of the Station Master and the Passenger Agent.[3] That year, shortly after some were installed, the terminal's board of directors wanted the murals removed. The board wanted to remove the murals and not install further murals in order to save money, though the chief engineer, Henry Waite, urged them to save them. He argued that the remaining installation would only cost $6,000, and that removing them and installing anything else would cost more. The effort saved the murals, and the board cut costs elsewhere.[2]

The concourse was demolished in 1974. Due to the impending demolition, the fourteen murals in the concourse were moved in 1973 at a cost of $400,000[8] to the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport.[2] A grassroots campaign named "Save the Terminal" raised the funds to save the works, though it could not raise sufficient funds to save the map mural at the west wall of the concourse.[9] The murals were difficult to move due to their extreme size and weight: they were attached to the concourse's interior wall, they were large in size, they utilized concrete in areas not covered by tiles, and steel frames were permanently placed around each mural. These factors made each work weigh approximately 8 short tons (7.3 t). Engineers spent three months working on the best method to remove the murals from the concourse walls. The panels were removed and encased in steel frames and lowered to steel cradles. Workers applied a protective coating to prevent tiles from moving or chipping, padded them in styrofoam, and crated them in wood. They were transported upright on a flatbed truck to avoid damage, and telephone wires and signs on the route to the airport had to be temporarily removed. The first murals arrived in August 1973, five hours after departing the terminal.[10]

Two of the industrial murals were shown in the airport in the 1988 film Rain Man.[11] In 1994, Delta spent $1 million moving five of the murals from one older airport terminal to a newer one.[12]

In 2015, with the airport's Terminals 1 and 2 slated for demolition, nine of the murals were relocated. They were moved to the exterior of the Duke Energy Convention Center, where a ceremony was held at the completion of the move in 2016. The airport board paid $1.45 million to remove and transport the works, and the City of Cincinnati paid $750,000 to restore, encase, and mount them.[13] Five Reiss murals remain in the main terminal at the airport.

The two Rookwood murals were not moved from their places until between 1989 and 1991, when they were relocated to the Cincinnati Historical Society's special exhibits gallery to make way for the installation of the Omnimax theater.[3][9]

In 2015, Matthew Lynch and Curtis Goldstein made modern interpretations of the murals using formica, a material invented and made in Cincinnati.[14] They were exhibited at the Weston Art Gallery in the city in 2018, along with the original photographic, crayon, and gouache studies Weiss made for the murals.[6]

Materials and depictions

[edit]The murals portray 35 workers of industries of Cincinnati, Ohio. They are to celebrate labor, a common theme for art at the time.[9] The works are 20 x 20 feet, and 8 inches thick, weighing 8 short tons (7.3 t).[13] They are silhouette mosaics, using mostly nickel-size colored glass tesserae, trimmed and shaped individually, imbedded in tinted mortar.[2] The tiles form the main elements of the murals, while colored plaster forms the backgrounds. This saved costs and provided a contrast in the works between the two different materials used.[1] The works were originally commissioned as oil paintings, though Reiss chose to make mosaics as the smoke from trains and cigarettes would damage oil paintings, they would be less visible in a smoke-filled room, and would be harder to clean. Thus Reiss paid for the additional cost of mosaic work out of his own commission. The oil murals in other parts of the terminal dulled and needed extensive restoration, as Reiss imagined.[9]

Several of the workers were identified as early as 1973. A muscular model and dancer, Lorne Kincaid, was used for 18 figures between all murals in the terminal. He likely posed for all the unnamed workers.[4] The Cincinnati Enquirer further revealed the identities of the workers in 2013, after eight months of research and about 2,800 emailed suggestions from readers. The workers and their firms were left anonymous, and the murals depicted the labor and laborers, not glorifying any bosses. Several of the workers depicted died while working, including Clem Vonderheide and Bill Ennix.[2]

Several of the companies depicted were utilized in the construction of the terminal; it featured American Oak Leather seats in the train concourse, and the train platforms and roundhouse used Philip Carey Company-built roofing.[15]

Gallery

[edit]-

Drug and chemical processing (William S. Merrell Chemical Company)

-

Radio broadcasting (Crosley Broadcasting Corporation)

-

Printing and publishing (U.S. Playing Card Co.)

-

Soap making (Procter & Gamble Co.)

-

Roof manufacture (Philip Carey Co.)

-

Meatpacking (E. Kahn's & Sons Co.)

-

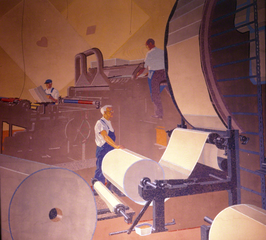

Machine tools manufacture (Cincinnati Milling Machine Company Factory)

-

Piano making (Baldwin Piano Company)

-

Ink making (Ault & Weiborg Corp.)

-

Sheet steel making (American Rolling Mills and Newport Rolling Mill)

-

Tanning (American Oak Leather Co.)

-

Laundry-machinery manufacture (American Laundry Machine)

-

Foundry products operations (Cincinnati Milling Machine Company foundry)

-

Airplane and parts manufacture (Aeronca Aircraft Company)

-

Pottery manufacture (Rookwood Pottery Company potter)

-

Pottery manufacture (Rookwood Pottery Company kiln master)

Further reading

[edit]- Garner, Gretchen (2016). Winold Reiss and the Cincinnati Union Terminal: Fanfare for the Common Man. Ohio University Press. ISBN 9780821422038.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Art of Union Terminal". Cincinnati Museum Center. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "After years of quiet labor, men in the murals are named". Cincinnati.com. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c "A Vision of Cincinnati: The Worker Murals of Winold Reiss" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-12. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ a b c d Art Deco and the Cincinnati Union Terminal; an exhibition organized by the Art History Department, University of Cincinnati. Contemporary Arts Center. January 11, 1973.

- ^ "Info" (PDF). library.cincymuseum.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-15. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ a b Arts, Cincinnati. "Matt Lynch & Curtis Goldstein: Work/Surface | Cincinnati Arts". www.cincinnatiarts.org. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ Cincinnati: A Guide to the Queen City and Its Neighbors. US History Publishers. Jun 15, 1979. ISBN 9781603540513. Retrieved Jun 15, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Weible, David Robert. "Cincinnati's Gorgeous Attempt to Woo Visitors, Circa 1933". CityLab. Archived from the original on January 22, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Emmis Communications (Nov 15, 1991). "Cincinnati Magazine". Emmis Communications. Retrieved Jun 15, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hudson, Carol A. (July–August 2011). "The Andrews Rolling Mill Mosaic Mural" (PDF). Bulletin of the Kenton County Historical Society. Kenton County Historical Society.

- ^ "Then and Now: A look back at 'Rain Man' in Cincy". WCPO. Feb 28, 2014. Retrieved Jun 15, 2020.

- ^ Tate, Skip (August 1994). "Airport Trivia". Cincinnati. CM Media. p. 70. ISSN 0746-8210. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ^ a b "Cincinnati-unveils-historic-murals-in-new-downtown". www.bizjournals.com. 2016. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ "Historic Reiss murals get fresh update". Cincinnati.com. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ Lacher, Walter S. (1933). "Cincinnati's New Union Terminal Now in Service". Railway Age. 94 (16): 574–590. Retrieved June 8, 2019.