Davenport brothers

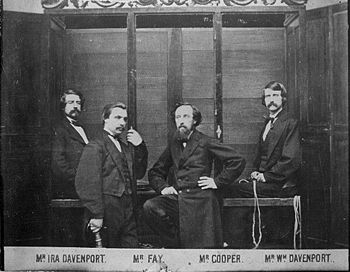

Ira Erastus Davenport (September 17, 1839 – July 8, 1911)[1] and William Henry Davenport (February 1, 1841 – July 1, 1877),[1] known as the Davenport brothers, were American magicians in the late 19th century, sons of a Buffalo, New York policeman. The brothers presented illusions that they and others claimed to be supernatural.

Career

[edit]The Davenports began in 1854, less than a decade after Spiritualism had taken off in America. After stories of the Fox sisters, the Davenports started reporting similar occurrences.[2]: 53 Their father took up managing his sons and the group was joined by William Fay, a Buffalo resident with an interest in conjuring.[2]: 53 Their shows were introduced by a former "Restoration Movement" minister, Dr. J. B. Ferguson, a follower of Spiritualism, who assured the audience that the brothers worked by spirit power rather than deceptive trickery. Ferguson worked as their stage manager.[3]

The Davenports caused a sensation around the world with their vaudeville act.[2]: 53 Their most famous effect was the box illusion. The brothers were tied inside a box which contained bells and musical instruments. Once the box was closed, the instruments would sound. Upon opening the box, the brothers were tied in the positions in which they had started the illusion. Those who witnessed the effect were made to believe supernatural forces had caused the trick to work.

The Davenports toured the United States for 10 years and then travelled to England where spiritualism was beginning to become popular. Their "spirit cabinet" was investigated by the Ghost Club, who were challenging their claim of being able to contact the dead.[4] The result of the Ghost Club's investigation was never made public. In 1868 the team was joined by Harry Kellar. Kellar and Fay eventually would leave the group to pursue their own career as a magician team.

William Davenport died on 1 July 1877 at the Oxford Hotel in King-street, Sydney, aged 36 years, during a tour of Australia and New Zealand. His death was attributed to "pulmonary consumption". The brothers had arrived from New Zealand three weeks previously; during the performances there William had "broke a blood vessel, and came to Sydney under the advice of his medical attendants".[5]

In 1895, Ira and Fay revived the act, but failed to attract an audience.[2]: 55 Ira died in New York in 1911.[2]: 55

Exposures

[edit]The Davenport brothers were exposed as frauds many times.[6][2]: 54–55 The stage magician John Nevil Maskelyne saw how the Davenports' spirit cabinet illusion worked, and stated to the audience in the theatre that he could recreate their act using no supernatural methods. With the help of a friend, cabinet maker George Alfred Cooke, he built a version of the cabinet. Together, they revealed the Davenport Brothers' trickery to the public at a show in Cheltenham in England in June 1865.[7]

Magicians including John Henry Anderson and Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin worked to expose the Davenport Brothers, writing exposés and performing duplicate effects. Edward Dicey who attended a séance in 1864 observed that there were a host of circumstances which suggested purposely designed trickery and described the Davenports performance as a "mere conjuring trick of no very high order".[8] He concluded that "all but the most confirmed believers will admit that, if it can be shown the Davenport Brothers can slip their hands out of the ropes, there is nothing supernatural, or even extraordinary, to explain in the exhibition." Dicey noted that the Davenport brothers employed three companions during their séances which was suspicious.[8]

Gymnast John Hulley and Robert B. Cummins followed the brothers around Britain. At a séance in Liverpool on the 15 February 1865 they were selected by the audience to tie the brothers. They tied the Davenports into their box with a Tom fool's knot that could not be easily removed and thus exposed the trick to audience who demanded their money back. The brothers were unable to untie themselves from the knot and Ira complained the rope was too tight.[9] Ira had begged their stage manager J. B. Ferguson to cut the knot with a knife and had received a hand wound in the process. The crowd was angry and a riot erupted with the cabinet being smashed.[3] The impresario P. T. Barnum included this expose in his 1865 book The Humbugs of the World.[10]

On 25 February 1865, Henry Irving and his fellow actors Philip Day and Frederick Maccabe who had read about the Liverpool exposure reproduced the Davenport brothers séance phenomena through trickery at the Library Hall of the Manchester Athenaeum.[11] Irving impersonated Dr Ferguson who had introduced the real Davenports. The imitation of the Davenports séance was successful and the audience cheered. The British newspapers praised Irving's expose and admired his acting skill. Irving and his actor friends were able to reproduce all the tricks of the Davenports and they repeated the performance at the Free Trade Hall to large crowds of influential people from Manchester.[11]

The Davenports were exposed in September, 1865 in Paris after one of the committee men noticed the ropes on the floor were not the originals.[3] A spectator rushed the stage, "put his hand on the bench round which the cords are wound, touches a spring, the bench bends in the middle, and the cords fall at the feet of the captives". The crowd were angry and highjacked the stage but the French Gendarmerie were able to restore order after promising a refund. During the riot the Davenports escaped the theatre.[3]

The Davenports were rejoined by William Fay for a final American tour before William Henry's death in 1877. Fay settled in Australia and Ira Erastus lived in America until the two reunited in 1895 and toured with a show that failed. The magician John Mulholland also exposed the tricks of the Davenport brothers:

A number of things immediately become less miraculous when it is known at times the Davenports employed as many as ten confederates. It was a night when a confederate was used that Alexander Herrmann (the stage magician known as Herrmann the Great) described in an article in the Cosmopolitan Magazine. The performance was being given in Ithaca, New York, and many Cornell College students were in the audience. They had brought "pyrotechnic balls so made as to ignite suddenly with bright light." When the lights were struck the Davenports were found to be on opposite sides of the stage waving musical instruments around in the air.[12]

Some from the spiritualist community also accepted that the Davenport brothers were fraudulent. From 1864–1869, Paschal Beverly Randolph worked on a biography of the Davenport brothers known as The Davenport Brothers: The World Renowned Spiritual Mediums, which was published by the brothers anonymously.[13] Randolph had been a friend of the brothers since the mid-1850s. However, he never published the work because he later came to the conclusion that the brothers were "deliberate impostors".[13] In his book Seership, Randolph publicly admitted he had been deceived by the brothers and regretted writing the biography. He wrote that "I am now satisfied that the data furnished were wholly untrue, and the alleged facts entirely imaginary, in a word, I believe that the D. B.'s are dead beats; in other words, that they are skilful jugglers, without the slightest real spiritual power about any of their performances."[14] Randolph became convinced of the fraud of the Davenports by the spiritualist M. B. Dyott who wrote an expose of the Davenports in the Religio-Philosophical Journal in October 20, 1866.[15]

Magician Chung Ling Soo revealed the brothers trick known as the "Davenport Tie" in 1898.[16]

Confession

[edit]According to the magician Harry Houdini, Ira had confessed to him that he and his brother had faked their "spirit" phenomena. Houdini in his book A Magician Amongst the Spirits (1924) also reproduced a letter from Ira claiming "we never in public affirmed our Belief in spiritualism." The author and spiritualist Arthur Conan Doyle refused to accept the exposures of fraud, and insisted that in private Ira was a practicing spiritualist.[17]

In 1998, skeptical investigator Joe Nickell discovered the Davenports' scrapbook from the museum at the Lily Dale Spiritualist Assembly. Nickell examined newspaper clippings, personal notes and photographs from the scrapbook. He concluded that Doyle was correct about Ira endorsing spiritualism in private and Houdini was also correct about their public "spirit" phenomena being the result of trickery. According to Nickell "taken as a whole, the evidence of the scrapbook does indicate that Ira Davenport was a practicing spiritualist, or at least pretended to be, although he and his brother used trickery to accomplish the effects they attributed to spirits."[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (1992). The Encyclopedia of Ghosts and Spirits. New York: Facts On File. pp. 81–83. ISBN 0-8160-2140-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Randi, James (1992). Conjuring. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-08634-2. OCLC 26162991.

- ^ a b c d Lande, R. Gregory. (2020). Spiritualism in the American Civil War. McFarland. pp. 84-85. ISBN 978-1-4766-8223-5

- ^ "The Ghost Club". Prairieghosts.com. Archived from the original on 2017-06-18. Retrieved 2014-07-25.

- ^ Death of One of the Davenport Brothers, Evening News (Sydney), 3 July 1877, page 2.

- ^ Christopher, Milbourne. (1990 edition, originally published in 1962). Magic: A Picture History. Dover Publications. p. 99. ISBN 0-486-26373-8 "The Davenports were exposed many times, not only by magicians but by scientists and college students. The latter ignited matches in the dark. The flickering flames disclosed the brothers, with their arms free, waving the instruments which until then had seemed to be floating. The exposures had little effect on that segment of the public which chose to believe the manifestations were genuine. They closed their minds to the truth and sat in awe, sure that spirits had been conjured up in their presence."

- ^ Steinmeyer, Jim (2005). Hiding the Elephant. Arrow. pp. 95–96. ISBN 0-09-947664-9.

- ^ a b Dicey, Edward (1864). "The Brothers Davenport". Macmillan's Magazine. 11: 35–40.

- ^ "Press Reports and Comments about the Exposure of The Davenport Brothers". johnhulley-olympics.co.uk. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ Barnum, P. T. (1866). The Humbugs of the World. New York: Carleton Publisher. pp. 136-137

- ^ a b Bingham, Madeleine. (2016). Henry Irving and The Victorian Theatre. Routledge. pp. 52-53

- ^ Mulholland, John . (1938). Beware Familiar Spirits. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 78. ISBN 0-684-16181-8

- ^ a b Deveney, John Patrick. (1997). Paschal Beverly Randolph: A Nineteenth-century Black American Spiritualist, Rosicrucian, and Sex Magician. State University of New York Press. p. 354. ISBN 0-7914-3119-3

- ^ Randolph, Paschal Beverly. (1896). Seership, the Magnetic Mirror. K. C. Randolph, Publisher. p. 36

- ^ Deveney, John Patrick. (1997). Paschal Beverly Randolph: A Nineteenth-century Black American Spiritualist, Rosicrucian, and Sex Magician. State University of New York Press. p. 466. ISBN 0-7914-3119-3

- ^ Soo, Chung Ling. (1898). Spirit Slate writing and Kindred Phenomena. New York City: Munn & Company. pp. 88-92

- ^ a b Nickell, Joe. (2001). Real-Life X-Files: Investigating the Paranormal. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 18-27. ISBN 0-8131-2210-4

Further reading

[edit]- Brereton, Austin. (1884). The Exposure of the Davenport Brothers. In Henry Irving: A Biographical Sketch. New York: Scribner and Welford.

- Mann, Walter. (1919). The Davenport Brothers. In The Follies and Frauds of Spiritualism. London: Watts & Co.

- Nichols, Thomas Low. (1864, reprinted 1976). Biography of the Brothers Davenport. ISBN 0-405-07969-9

- The Davenport Brothers: The World Renowned Spiritual Mediums. Boston: William White and Company, 1869.