Willem van Haecht the Elder

Willem van Haecht, sometimes also Willem van Haecht the elder to distinguish him from the painter Willem van Haecht[1] (ca 1530 – after 1585) was a Flemish poet writing in the Dutch language. He was also a cloth merchant, draughtsman, a bookseller and publisher.[2][3] He was a member since 1552 and from 1558 a factor of the chamber of rhetoric De Violieren in Antwerp.[2] In that role he played an important part in the transition of the development of theatre in Flanders from plays mainly dealing with epic, moralising or allegorising themes towards plays expressing the humanist ideas of the Renaissance.[4] He published the Psalms of the Bible in Dutch verse and also wrote poems and songs.[5]

A supporter of the Calvinist cause, he fled to Aachen in 1567 when the religious persecution of Calvinists in the Low Countries intensified upon the arrival of the new governor, the Duke of Alva. Van Haecht returned to Antwerp in the early 1570s, but left his home town again after the Fall of Antwerp in 1585 as Calvinists were then forced to choose between renouncing their religious allegiance or leaving the Spanish Netherlands.[2]

Life

[edit]Early years

[edit]Willem van Haecht was born in Antwerp around 1530 in a family of painters and engravers.[6] He is believed to have trained as a draughtsman.[2] He enjoyed a humanist education and could likely read Latin.[7]

Willem van Haecht was active as a cloth merchant.[3] As early as 1552, van Haecht was affiliated with the chamber of rhetoric De Violieren, which was the most prominent chamber of rhetoric in Antwerp. It was linked to the local artists' Guild of Saint Luke and included among its members leading Antwerp sculptor and architect Cornelis Floris de Vriendt and painter Maerten de Vos. Van Haecht became a factor (poet in title) of De Violieren in 1558, probably succeeding Jan van den Berghe who was ill.[6]

Literary career

[edit]In May 1558, van Haecht wrote a morality play called Het spel van Scipio (The Game of Scipio), which was performed by his companions before the magistrate and other chambers of rhetoric.[8] This play has not been preserved.[7]

In 1561 a large competition of 13 chambers of rhetoric in the Duchy of Brabant was organised by the Antwerp chamber of rhetoric De Violieren in Antwerp. The competition called 'landjuweel' in Dutch ('jewel of the land') was held at 7-year intervals between 1515 and 1541. But because of the public turmoil in the Low Countries there was an interruption of 20 years before De Violieren, which had won the last landjuweel, organised another edition of the competition. A landjuweel involved performances of drama, processions, tableaux vivants and recitations of poetry.[9] An estimated 5,000 participants from twelve different cities traveled to Antwerp for the 1561 event.[10]

Van Haecht as the factor of De Violieren wrote the invitations and introductory material for the 1561 landjuweel.[11] This material was intended as a sort of mission statement for the event and gave it a political, literary and economic framing. In the 1561 competition the participating chambers were required to provide a solution for the issues of peace, knowledge and community in every part of the competition.[10] The invitation and moralities of the competition, as well as other poetic works, were published in 1562 under the title Spelen van sinne, vol scoone moralisacien, vvtleggingen ende bediedenissen op alle loeflijcke consten with a preface by van Haecht.[12] The Caerte or invitation letter for the landjuweel was written by van Haecht in the form of a poem of 13 stanzas of 11 lines (rhyme scheme AABAABBCBBC) and starting and ending with the motto of De Violieren which was Vvt ionsten versaemt (gathered in a spirit of goodwill).

The prologue to the actual plays written by van Haecht describes how Rhetorica has been sleeping in the protective lap of Antwerp where it was discovered by three nymphs. The first two plays performed prior to the actual start of the landjuweel were by the hand of van Haecht. The first play called Oordeel van Tmolus tusschen Apollo en Pan, deals with the mythological theme of the judgement of Midas. Midas had ruled in favour of Pan in a musical performance competition between Apollo and Pan. As punishment Apollo had transformed Midas' ears into ass' ears. Midas tried to hide his ears from god but failed to do so. Apparently, the author wanted to produce a Renaissance work, while drawing his material from classical mythology. However, in the second part of the play, it turns into medieval sotterny (farce). Van Haecht also wrote the second preliminary play that was called the Prologue in which he extolled the virtue of unity. Van Haecht also wrote the farewell piece, Oorloff oft Adieu, and the closing piece of another theatre competition held at the same time as the landjuweel referred to as haagspel. In the farewell piece, he advances the thesis that the decadence of Rome and that of other ancient empires should not be attributed to the disbelief or rejection of God, but to the decline of the arts.[4]

The Royal Library of Belgium holds a bundle of documents referred to as the Landjuweel van Antwerpen, 1561 (catalogue number II 13.368 E (RP)).[13] It is made up of all kinds of loose, unnumbered papers of different sizes, some printed and others handwritten. The date 1561 is incorrect, since a chorus dated to 1578 is included. This heterogeneous collection of papers, a number of which are related to the landjuweel of 1561, was likely bundled by Willem van Haecht. He added the following pieces written by himself: a chorus on Om datmen vianden moest voor vrienden houwen (Because one has to treat enemies as friends) (1576), a chorus on Godt slaet en geneest, den droeuen hy blijde maeckt (God hits and heal and makes the sad happy) and a chorus on De rijcke weet qualijck hoe daerme te moey is (The rich do not understand how tired the poor are). The last page of the bundle of papers has about 20 verses, probably from a chorus on Betrout in Godt, Hy en sal v niet verlaten (Trust in God and he will not leave you).[14]

Van Haecht produced three plays on the acts of the Apostles, which were performed by De Violieren in 1563, 1564 and 1565. In the manuscript, preserved in the Royal Library of Belgium, the plays are entitled Spel van Sinnen van dwerck der Apostelen (Morality on the Acts of the Apostles). In these plays van Haecht gives expression to his moderate Lutheran views and his interest in antiquity. In the plays van Haecht criticises the clergy and the persecution of Protestants. His moderate views based on the Augsburg Confession are clear from the fact that he distances himself from sects that were considered more radical such as the anabaptists and argues for civic unity in religious and social matters. In the plays he further shows that he rejected religious dogmatism in favor of tolerance and was opposed to the iconoclasm of certain Calvinists. According to his nephew Godevaert van Haecht the plays were liked by the general public but angered the Catholic clergy. Through these plays the chambers of rhetoric De Violieren tried to exert an influence on the religious and social conversation in Antwerp of the time.[15] During the performance of the play some books were burned on the stage according to the stage directions.[16]

In 1564 van Haecht won the third prize at the competition of another chamber of rhetoric in Antwerp, the Goudbloem.[6] He was likely the author of an untitled publication, which is usually referred to as Dry Lamentatien oft Beclaghinghen (Three Lamentations), printed in 1566 by an unknown publisher at an unknown location.[14] A copy in the Ghent University Library is listed in the library catalogue as being the work of Laurens van Haecht Goidtsenhoven even though it is signed with the initial W.V.H.[17] Above each piece in the publication is a detailed title, in which the author calls each poem an "argument", which is consistent with the content.[14]

Exile and return

[edit]

With the arrival of the Duke of Alva in the Low Countries in 1567 the fairly tolerant religious climate was replaced by one of persecution of those who no longer adhered to the Catholic faith. Van Haecht fled to Aachen and subsequently to the northern Netherlands.[15]

Van Haecht returned to Antwerp in the 1670s. When, in 1578 the Lutheran congregation was restored in the city, he started openly practicing his Protestant faith again. In the same year he published engravings which represented the Lutheran doctrine of grace.[6] The following year, his rhymed translation of the Psalms was published for the benefit of the Lutheran congregation of Antwerp. Its editions carry the privilege of two Catholic princes: the first, from 1579, that of the Archduke Mathias, and that of 1583, strangely, that of the Duke of Parma. This indicates that at the time, the followers of the Augsburg Confession in Brabant were hardly oppressed by the Reformers. The second edition also contains an appendix containing a Dutch translation of the Gloria Patris, translated in seven ways.[18][19]

Van Haecht was a friend of the Brussels-based humanist and author Johan Baptista Houwaert. He compared Houwaert to Cicero in the opening eulogy of the Lusthof der Maechden written by Houwaert published in 1582 or 1583. In his eulogy van Haecht further states that every sensible man should recognize that Houwaert writes eloquently and excellently.[20]

The last record about van Haecht dates from 1583. If he was still alive in 1585, he would likely have left Antwerp again, for parts unknown, in 1585 or shortly thereafter, upon the take-over of Antwerp by the Catholics, unless he had already died.

Poetry

[edit]He also wrote smaller poems, including some highly religious songs and choruses, some dialogues, three 'lamentations', a translation of the five lamentations of Jeremiah and arrangements of the Psalms, partly recorded in the hymnbook of the Dutch Lutheran church.

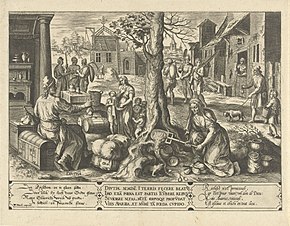

He published many prints during a fairly brief period between 1577 and 1580. During this period he worked closely with the Antwerp engravers Hieronymus Wierix, Johannes Wierix and Anton Wierix the younger. Some of the prints were engraved by Hans Bol. Artists such as Maerten de Vos, Marten van Cleve and Chrispijn van den Broeck. The prints were issued as single sheets, in pairs or in the form of a series. Most of their subject matter was political and was treated in an allegorical manner. In some cases, Willem van Haecht shared the credit for conceiving and publishing some of these works with his nephew Godevaert van Haecht.[5]

Lyricist

[edit]Van Haecht wrote the lyrics to various songs usually of Christian inspiration. This includes the Dutch lyrics to a polyphonic song in five voices, Ghelijc den dach hem baert, diet al verclaert.[21] This song was presumably composed by Hubert Waelrant for the opening play of De Violieren at the landjuweel of 1561 that van Haecht had written himself. The poem was also printed on a flying sheet with the musical notation. Van Haecht's poem Hoe salich zijn die landen that he wrote for De Violieren was set to music by Jacob Florius and was included in the Geuzenliedboek, a collection of songs of those who revolted against Spanish rule in the Low Countries.[22]

Willem van Haecht had two songs included in the Refereynen ende liedekens van diuersche rhetoricienen vvt Brabant, Vlaenderen, Hollant, ende Zeelant: ghelesen en ghesonghen op de Corenbloeme Camere binnen Bruessele ... op de vraghe, wat dat de landen can houden in rusten?, printed by Michel van Hamont in Brussels in 1563. The song were a chorus on Den wysen Raet die de Kennis des Heere heeft (The wise counsel that the knowledge of the Lord entails) and a song that starts with the Aenhoort ghy Adams saet (Listen to Adam's seed).[14]

A further three songs are in a collection of documents by Willem de Gortter (Royal Library of Belgium): a chorus on In Christus woort is verborghen d'eeuwich leuen (In Christ's word is hidden the eternal life) (1563); a chorus on Eyghen liefde die elcx herte verblinden can (Self love can blind every heart) and a song which starts with Ontwecket mensch tis meer dan tijt (Wake up everyone, it's more than time).[14][23]

References

[edit]- ^ Willem van Haecht (I) at The Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- ^ a b c d J.J. Mak en D. Coigneau, Willem van Haecht in: G.J. van Bork en P.J. Verkruijsse, 'De Nederlandse en Vlaamse auteurs', De Haan, 1985, pp. 475–476 (in Dutch)

- ^ a b J. Van Roey, 'Het Antwerpse geslacht van Haecht (Verhaecht). Tafereelmakers, schilders, kunsthandelaars', in: Miscellanea Jozef Duverger. Bijdragen tot de kunstgeschiedenis der Nederlanden, Gent 1968, dl. 1, p. 216-229 (in Dutch)

- ^ a b G.P.M. Knuvelder, Handboek tot de geschiedenis der Nederlandse letterkunde. Deel 1, Malmberg, 1978, pp. 476–478 (in Dutch)

- ^ a b James Clifton, The Triumph of Truth in an Age of Confessional Conflict, in: Walter Melion, Bart Ramakers, 'Personification: Embodying Meaning and Emotion', Brill, 2016, pp 166–167

- ^ a b c d Van Bruaene, Anne-Laure. Om beters wille: rederijkerskamers en de stedelijke cultuur in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden 1400–1650, Amsterdam University Press, 2008, pp. 133–134 (in Dutch)

- ^ a b Anke van Herk, Fabels van liefde, Amsterdam University Press, 2011, p. 52 (in Dutch)

- ^ De liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche sint Lucasgilde van 1453–1615, edited and published by Ph. Rombouts and Th. van Lerius, Antwerp, 1872–1876, p. 211 (in Dutch)

- ^ John Cartwright, The Politics of Rhetoric: The 1561 Antwerp Landjuweel, in: Comparative Drama Comparative Drama Vol. 27, No. 1, Continental Medieval Drama (Spring 1993), pp. 54–63

- ^ a b Jeroen Vandommele, Als in een spiegel: vrede, kennis en gemeenschap op het Antwerps Landjuweel van 1561: vrede, kennis en gemeenschap op het Antwerpse Landjuweel van 1561 (Middeleeuwse studies en bronnen, Band 132), Hilversum Verloren, 2011 (in Dutch)

- ^ Mak, Jacobus Johannes, et Dirk Coigneau, De Nederlandse en Vlaamse auteurs van middeleeuwen tot heden met inbegrip van de Friese auteurs (red. Gerrit Jan van Bork et Pieter Jozias Verkruijsse), Weesp, De Haan, 1985, p. 244-245 (in Dutch)

- ^ Spelen van sinne, vol scoone moralisacien, vvtleggingen ende bediedenissen op alle loeflijcke consten, by M. Willem Siluius, drucker der Con. Ma., 1562, at archive org (in Dutch)

- ^ Online copy of the Landjuweel van Antwerpen, 1561 in the Royal Library of Belgium (in Dutch)

- ^ a b c d e G. Jo Steenbergen, Refereynen en andere kleine gedichten van Willem van Haecht in: De Nieuwe Taalgids. Jaargang 42 (1949), pp. 161–134 (in Dutch)

- ^ a b Louis Peter Grijp, Conformisten en rebellen: rederijkerscultuur in de Nederlanden (1400–1650) (red. Bart A. M. Ramakers), Amsterdam University Press, 2003, p. 181–183 (in Dutch)

- ^ W.M.H. Hummelen, Inrichting en gebruik van het toneel in de Amsterdamse Schouwburg van 1637. Amsterdam 1967, p. 78 (in Dutch)

- ^ Laurens van Haecht Goidtsenhoven, Drye Lamentatien oft beclaginghen ... at the Ghent University Library (in Dutch)

- ^ Witsen Geysbeek, Pieter Gerardus, Biographisch anthologisch en critisch woordenboek der Nederduitsche dichters, vol. 3, HAE-IPE, C.L. Schleijer, Amsterdam, 1822, p. 1-4 (in Dutch)

- ^ Achtergrondinformatie over de vier kerkboeken in: De Psalmen Dauids(1583)–Willem van Haecht (in Dutch)

- ^ Kalff, Gerrit, Geschiedenis der Nederlandsche letterkunde, vol. 3, Groningue, J.B. Wolters, 1907, p. 272-273, 278–282, 286–287, 289–290 (in Dutch)

- ^ Ghelijc den dach hem baert, diet al verclaert at youtube

- ^ Jan Willem Bonda,, De meerstemmige Nederlandse liederen van de vijftiende en zestiende eeuw, Hilversum, Verloren, 1996, pp. 206, 216 (in Dutch)

- ^ Handschrift van Willem de Gortter in the Royal Library of Belgium (in Dutch)

External links

[edit] Media related to Willem van Haecht the elder at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Willem van Haecht the elder at Wikimedia Commons